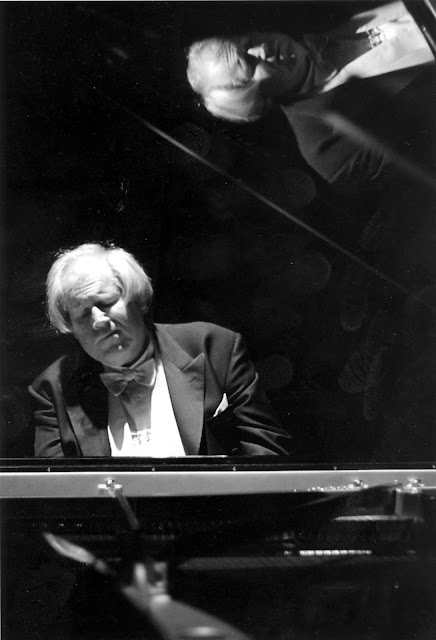

Grigory Sokolov live in Warsaw 27 October 1992 - A glorious memory revived by Polskie Radio Dwojka

|

| Grigory Sokolov |

This afternoon I was busy writing as usual researching the life of my great-uncle the brilliant pianist Edward Cahill. I was exploring his friendship in Switzerland after WWII with the great German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler. They met whilst having cell regeneration therapy in October 1945 at Dr. Niehans' Clinque La Prairie at Clarens on the shores of Lac Leman (Lake Geneva). I was reading a written apologia given personally to Cahill wherein Furtwängler justifies and explains his notorious decision to remain in Germany conducting concerts under the Nazis. I was listening to his April 1953 Berlin recording of Beethoven's Symphony No.7 in A major with the Vienna Philharmonic.

A green glow and I noticed the radio tuner was on as I had been listening to the wonderful Radio Dwojka earlier in the morning. I decided to switch it off by remote control and pushed the 'Tuner' button which unexpectedly switched off the Beethoven and reconnected me to the radio.

There was a pianist playing a Brahms Intermezzo from Op. 117. I continued to listen as the tone and touch were superb and then my emotions and spirit began to be moved in the most inexplicable and magical manner. I thought 'Who can this possibly be who is playing like this?' I then began to be reduced to a tearful state by these profound Brahmsian utterances and thought 'Only one pianist ever affects me in this profound manner, and that is Grigory Sokolov.' I waited anxiously for the radio announcement, absolutely convinced it was him.

I was correct. 'But why are they broadcasting this? Oh God, has he died?' But Radio Dwojka were broadcasting one of their regular series of 'Memorable Concerts'. Then they announced the date of the concert we were listening to as that of 27 October 1992 in the Warsaw Philharmonic Hall - my first year in Poland. I had heard Sokolov for the first time earlier in that year at the Chopin Museum on the 'agreed date' of Chopin's birthday - 22 February.

As a 'Writer's Cut' I quote my account of the first time I heard Sokolov in concert from the unedited manuscript of my book on Poland A Country in the Moon. This passage disappeared in editing along with 28,000 other words from the final published manuscript:

Each year the Kościół Świętego Krzyża (Holy Cross Church) is the site for a concert and ceremony to celebrate Chopin’s birth on 22 February 1810. Wreaths are laid at the plaque behind which lies the urn that contains his heart brought from Paris by his sister Ludwika Jędrzejewicz. His body was interred at the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. It is a small and remarkably moving ceremony. Many private people move forward to lay single blooms or bunches of flowers while the organist plays a festive organ work. Two beautiful children, one a tiny three year old in a red bobble hat, laid a single tulip. This simple ceremony set the tone of nostalgia and melancholy for the day.

After I had laid my single red rose I walked to the monumental brick Cytadela (Citadel) on Żoliborz Hill, built by the Tsarist authorities after the November Uprising of 1830 against the Russians. I wanted to immerse myself in the historical source of so much of Chopin's anguished music. Tsar Nicholas I exacted a terrible revenge for being dethroned as King of Poland. The sledges and columns of prisoners soon began to leave for Siberia. The Citadel was built high on the Vistula escarpment to intimidate Warsaw and hold thousands of political prisoners for interrogation, torture and execution. By September 1831 the Kingdom had once again fallen under the Russian yoke and a distraught Chopin wrote in his Stuttgart diary in painful, dislocated sentences:

'The suburbs in ruins - burnt down - Jaś - Wiluś no doubt died on the ramparts - I see that Marcel has been imprisoned - Oh God, have You not had enough of Moscow's crimes – or – or – You are a Moscovite yourself! …..sometimes I only groan and express my pain on the piano - I am in despair……’.

An undocumented tradition states that he wrote the ‘Revolutionary’ Study in C-minor and the final tempestuous Prelude in D-minor while in Stuttgart after the fall of Warsaw. Princes and nobles were humiliated and Polish officers in their thousands were exiled to the Caucasus. Intellectuals, agitators and insurrectionists were executed on the steep slopes or in the fosses of this Citadel. The spirit of fierce resistance alternating with hopeless pain and despair are the womb of Chopin's patriotic music, not the salons of Paris although later in his life they too played their part.

It was snowing heavily and -6C as I laboured up the Żoliborz Hill through the neoclassical ‘Execution Gate’ near the site of the gallows that had stood under a broad chestnut tree. A forest of crosses on the wooded slopes marks the place where thousands suffered a miserable death, particularly following the subsequent January Uprising of 1863. After this hopeless gesture tens of thousands of young people were marched to their deaths in Siberia. The nation never recovered. Many of the leaders passed through the Wrota Iwanowskie (Death Gate) and along Death Road into the horrors of Pavilion X.

The approach to the museum in winter is across a bleak, open area with snow-covered cannons, broken bricks and striped sentry boxes. A black wagon used for collecting prisoners around Warsaw for transport to Siberia was parked negligently at the entrance. The museum contains fascinating documents, tickets of incarceration, chessmen made of bread, prisoner's photographs (the Tsarist police would shave off half the hair, moustache and beard to mark a convict and so prevent easy concealment).

So many men of brilliant intelligence and creativity perished here between 1822 and 1925. My friend Irena who is a custodian says she is distinctly aware of the metallic smell of blood in the corridors. Paintings, daguerreotypes and photographs record endless lines of tattooed, tattered prisoners - portraits of men of striking intelligence and sensibility - heading off on foot into the icy wastelands. The prisoners were forced to walk some five thousand kilometers from Warsaw to Siberia, a journey on foot that took eighteen months if you managed to survive. Wealthy families riding on a sledge might be permitted to accompany the condemned men. At the Siberian camp men were chained permanently night and day to their wheelbarrow, sleeping with this ghastly succubus and finally dying upon it. I slipped on the frozen cobbles of Death Road.

It was against this historical background I was to listen to a Chopin recital in the Chopin Museum given by the Russian pianist Grigory Sokolov. The electricity of anticipation was in the air as his reputation preceded him. The audience was the customary group of elderly Central Europeans with the ravages of high culture etched into their faces together along with the ubiquitous Japanese music students. The instrument was placed near the serliana under a blazing chandelier. Sokolov emerged from the artist's door and walked to the piano. He was most unprepossessing in appearance - a bearish Russian figure with rather muscular hands.

Within a few seconds of the impassioned opening bars of the C-minor Polonaise I knew I was in the presence of true greatness, playing of profound spiritual intensity and technical achievement. The cantabile love melody that forms the centerpiece of the work was intensely lyrical. The passionate, patriotic nature of Chopin, the revolutionary fervour carried one away. We passed through a programme of brooding extremes, from a group of mazurkas haunted by rural nostalgia to the the tragic nobility of the symphonic F-sharp minor Polonaise with its brutal, repetitive, military central section which linked me directly to the Citadel, a military snare drum approaching, passing and retreating.

He received a standing ovation and spectacular bunches of flowers (a charming tradition of all concerts in Poland). Placing them to one side of the music desk he launched into the mighty twelfth Etude from the Op.25 set. There is something frightening in his intensity, the deeply disturbing feeling of a man in touch with a pure creative force. The greatest living pianist to my mind.

I embraced him spontaneously in the Artist’s Room after he signed my programme. This was the first time and possibly the last I would ever feel impelled to act on such emotion after a piano recital. I stumbled out into the snow in a temperature around -10C in a daze to make my way home to the forest prison where I worked.

He played a formidable programme that evening:

Brahms Intermezzi op. 117, Ballades op. 10, 2 Rhapsodies op. 79

Chopin Polonaise-Fantasie A flat major op. 61, Sonata B-flat minor op. 35

How far into the azure Sokolov wings in sensibility and profound spirituality above nearly all pianists playing today. Words are absolutely inadequate to express the movement of the soul he can create in one, that almost unbearable yearning of Brahms that suffuses these works. The Chopin Polonaise-Fantasie was a truly great reading of this complex and demanding mature work of Chopin, beset as he was at the time by all sorts of suffering. I heard him play it again once at the Duszniki Zdroj Festival in an unforgettable performance.

'

There are pianists and then there is Sokolov.'

There are pianists and then there is Sokolov.'

Clouds obscuring memory began to lift as he opened the Chopin B-flat minor Sonata. It burst upon me with a start and even a lurch of foreboding that I was about to hear once again in my life the most deeply moving Marche funèbre: Lento movement I had ever heard - and I have heard literally hundreds. Ever since that evening in 1992 I have quoted this performance to my many musical acquaintances as the consummate interpretation of this movement. Pianists are nearly always unable to plumb the depths of this ghastly statement. We have heard it too often.

The intensity of Sokolov was as if a close member of his immediate family had died that very day and he was devastated by grief. The tempo to begin was slow, the dynamic almost pianissimo, the ominous beat of mortality, the inexorable destiny of death that will come to us all. So slow, so insidious, so quiet it was like a dark premonition falling over us like a suffocating cloak. Then the anguished cry of humanity in the face of it, the desperate courage and resilience to embrace life in the face of the inevitable

'Do not go gentle into that good night,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.'

as the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas would put it over a hundred years later.

The lyrical simplicity of the central section Sokolov portrayed with the simplicity of childhood, the beauty of our human nature and its supreme innocence. The glory of unsullied Nature and poetic nostalgia for past joys. Tears formed as this wonderful song rose. Again it came, once again, the inexorable, the stealthy, the persistent ominous murmer of the abyss as Sokolov presented us with it, yawning and gaping there, the terrible emotion of gazing into it and then our cry. The hectic wind over the graves of the Presto, his formidable technique able to achieve the effect of a chill zephyr cutting with icy fingers into the corners of tombstones.

The whole of human life was laid out in this operatic, magisterial even terrifying account, its tragic nature hackneyed almost to insignificance by ubiquitous repetition - but not in this performance my friends, not in this recreation of the coming of the Commendatore.

An unnerving experience indeed and one no other living pianist could possibly achieve. You cannot be taught to feel. You cannot be taught sensibility. The ability to express a wide range of emotions comes from within the heart. It is a gift of God made up in music of innumerable microscopic hesitations and accelerations, indeterminate fluctuations of dynamic and phrasing, subtle variations of articulation, a wide palette of colours and nuance, a tone and touch that emerge organically from within the soul. Such profound and refined musical gestures are instinctive and cannot be learned. Furtwängler once said that 'an interpreter can render only what he has first lived through.'

Yes, there were smudges and 'wrong' notes in the first and second movement as result of Sokolov's passion but he was risking everything like a true explorer and it mattered not a jot. The urgency controlling these minor imperfections were the very reason this performance was so prodigious.

Oddly enough his recorded live performance of this work is not nearly as moving and profound as on that particular night. If you buy it you may be disappointed given my description. But that is the way of unpredictable performances in music - 'that cabbalistic craft'.

Chastened and thoughtful I return to my work on Furtwängler and my great-uncle, more than ever convinced of the towering figure of Sokolov in contemporary pianism....

Thank you Dwojka so very, very much!

Thank you Dwojka so very, very much!

My book on Poland:

A Country in the Moon: Travels in Search of the Heart of Poland (London 2009)

(English) http://www.michael-moran.net/poland.htm

Kraj z Księżyca. Podróże do serca Polski (Warsaw 2010)

(Polish)