Lutosławski Centenary Concert Warsaw 25 January 2013 - Anne-Sophie Mutter performs works dedicated to her

|

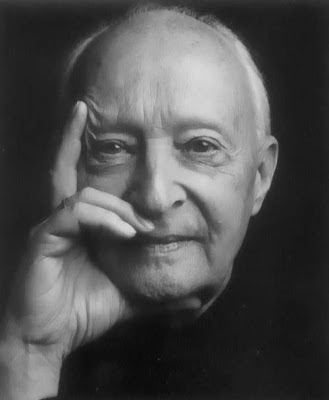

| The noble and fastidious face of the Polish composer Witold Lutosławski 25 January 1913 - 7 February 1994 |

It was during my earliest remarkable encounters with Poland and working in Warsaw in the early 1990s that I first encountered the music of Witold Lutosławski. Already ill with cancer and frail, in his last public performance he conducted his Fourth Symphony at the 1993 Warsaw Autumn Festival. I have never forgotten this profound musical experience.

During this concert I was accelerated back to my rather unusual reverse exposure to classical music. In the 1960s, long before I was at all familiar with the conventional classical repertoire, I had attended concerts, listened to recordings and studied the fascinating 'avant-garde' (so-called at that time) scores of only living composers such as Pierre Boulez, Henri Pousseur, Iannis Xenakis, Mauricio Kagel, Cornelius Cardew, Krzysztof Penderecki, Luciano Berio, Luigi Nono and John Cage. In 1968 I spent months in Cologne as a writer, not a musician, observing the astounding course and development of the work of Karlheinz Stockhausen.

There is no greater musical and metaphysical experience than attending a concert of music performed by the living composer himself. This feeling was particularly strong when say Stockhausen was 'at the controls' of his space craft in the mind-expanding space flights one takes through the various Regions of his masterpiece Hymnen, comparable only to such works as Beethoven's Missa Solemnis. I have not remained the same being after listening to the version with orchestra in 1968 in Bruxelles. This work is perhaps the greatest truly contemporary expression of man's existential isolation, his attempts to relate across cultures yet at the same time aware of his subconscious loneliness floating like the atom he is in the vast and ever expanding cosmos.

There is no greater musical and metaphysical experience than attending a concert of music performed by the living composer himself. This feeling was particularly strong when say Stockhausen was 'at the controls' of his space craft in the mind-expanding space flights one takes through the various Regions of his masterpiece Hymnen, comparable only to such works as Beethoven's Missa Solemnis. I have not remained the same being after listening to the version with orchestra in 1968 in Bruxelles. This work is perhaps the greatest truly contemporary expression of man's existential isolation, his attempts to relate across cultures yet at the same time aware of his subconscious loneliness floating like the atom he is in the vast and ever expanding cosmos.

One of the very greatest of all composers, Olivier Messiaen, was alive then (I remember his long, multi-coloured scarf illuminating a darkened Westminster Cathedral after a spiritually demolishing performance of Et Expecto Resurrectionem Mortuorum, a scarf as colorful as his birds flying below the abyss of the unfinished cathedral roof).

It had been the same epiphany when I actually heard Lutosławski conduct his own work.

Further spinning back in time to Alban Berg, Anton Webern, Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, Benjamin Britten, Bela Bartok, Edward Elgar, Claude Debussy, Richard Wagner....and then I stopped my rearward travels. I think journeying chronologically 'backwards in time' sensitized my ears and made the appreciation of the revolutionary nature of much music of the so-called 'past' perhaps more acute than a conventional 'forward developmental' approach. I am sure this unusual experience has enabled me to hear the past in a new way. Time is a spiral for me...

How curious though that now I am so deeply engaged in the world of Wilhelm Furtwängler’s visionary Beethoven readings and his own engagingly tonal Second Symphony of 1948 (he felt serialism was a dead end), William Christie and his superb productions of Baroque opera, Wanda Landowska's luminous Mozart on the piano (no, not the harpsichord), the philosophical Bach of Grigory Sokolov, myself playing Chopin on an historical Pleyel instrument, the rococo world of Antoine Watteau and the clavecin music of Francois Couperin. In age I seem to have become a slave of 'old-fashioned' tonality and melody when once I exclusively embraced the 'avant-garde' with a vengeance. Why has this happened I ask myself? The answer could be worrying.

It had been the same epiphany when I actually heard Lutosławski conduct his own work.

Further spinning back in time to Alban Berg, Anton Webern, Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, Benjamin Britten, Bela Bartok, Edward Elgar, Claude Debussy, Richard Wagner....and then I stopped my rearward travels. I think journeying chronologically 'backwards in time' sensitized my ears and made the appreciation of the revolutionary nature of much music of the so-called 'past' perhaps more acute than a conventional 'forward developmental' approach. I am sure this unusual experience has enabled me to hear the past in a new way. Time is a spiral for me...

How curious though that now I am so deeply engaged in the world of Wilhelm Furtwängler’s visionary Beethoven readings and his own engagingly tonal Second Symphony of 1948 (he felt serialism was a dead end), William Christie and his superb productions of Baroque opera, Wanda Landowska's luminous Mozart on the piano (no, not the harpsichord), the philosophical Bach of Grigory Sokolov, myself playing Chopin on an historical Pleyel instrument, the rococo world of Antoine Watteau and the clavecin music of Francois Couperin. In age I seem to have become a slave of 'old-fashioned' tonality and melody when once I exclusively embraced the 'avant-garde' with a vengeance. Why has this happened I ask myself? The answer could be worrying.

And so last night at the Warsaw Philharmonia I was somewhat discomforted and then elated when catapulted back to my atonal and aleatoric youth during the Lutosławski Centenary concert. One of the world's great musicians, the beautiful and elegant virtuoso violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter had come to Warsaw to perform works that Lutosławski had dedicated to her and to receive a medal and a statuette for her selfless musical work and extra-musical philanthropy.

In the foyer there was an illuminating although slightly esoteric attempt to clarify precisely what Lutosławski was inspired by (paintings, literature) and the compositional processes he was engaged in (say 'controlled aleatorism' and' Chain' composition).

We first heard the composition Sostenuto for Orchestra (2012) by Pawel Szymanski who is the National Philharmonic Orchestra's Composer in Residence for the 2012/2013 season. This was a commissioned work dedicated to the memory of 'Luto'. This was a fine work of complex rhythmic structure and instrumental timbres. One would have needed to be familiar with Lutosławski's symphonies to fully appreciate the gestures of reminiscence.

We then heard Lutosławski's magnificent Third Symphony (1981-83), a true masterpiece of the modern 20th century repertoire and performed rather more often than many of his works. The Berlin Philharmonic with Sir Simon Rattle performed the work this year at the Proms in London.

The opening brass 'salvoes' had clearly been mirrored in the previous valedictory piece. Here was Lutosławski 's unique developed voice that seems to owe so little to the past. Antoni Wit conducted the Warsaw Philharmonic in a far more lively and committed manner than usual, both conductor and orchestra seemingly quite at home with Lutosławski's concept of 'limited aleatorism' whence the musicians play phrases or fragments in their own time. I was strongly reminded of the energy, diverse and incisive orchestral colours of Olivier Messiaen's Turangalila Symphony, although Lutosławski did not have a love narrative here as did Messiaen or share the French composer's obsession with birds and the sounds of the Orient.

At the period the Third Symphony was written Poland was labouring under Martial Law and if one realizes this the martial elements seem to have a clear reference although he would probably have denied that it had any such 'programme' of suffering, hope and resolution.

However as Thomas Mann showed in his great musical novel Dr. Faustus, a composer can subconsciously express profoundly the torture and suffering of his time without fully realizing what he is accomplishing. I feel one cannot listen to this work in a linear developmental fashion but see the work from above, laid out as it were in an instantaneous glance of the eye or rather ear, complete as a whole, a superb and beautiful oriental carpet containing a wonderful variety of colours and woven sound.

In the recent brilliant Jagiellonian Exhibition mounted in Warsaw at the Royal Castle and National Museum, I saw a large painting of the Passion of Christ brought from Torun and painted in 1470-80. All the sufferings of the Saviour were depicted at once in no particular chronological linear order which is the way one normally traverses the conventional Stations of the Cross in a church. In this panel one embarks on a sort of travel adventure, exploring this or that moment of Christ's familiar suffering not pictorially related in time but which finally accumulates to make an entire powerful Gestalt of his suffering. The picture is a type of what one might conveniently term a 'simultaneous painting'. This seemed absolutely analogous to such a piece of music as the Third Symphony by Lutosławski. One fixes and absorbs discrete details, complete passages and forms which create a final cumulative overwhelming effect upon completion.

In the foyer there was an illuminating although slightly esoteric attempt to clarify precisely what Lutosławski was inspired by (paintings, literature) and the compositional processes he was engaged in (say 'controlled aleatorism' and' Chain' composition).

We first heard the composition Sostenuto for Orchestra (2012) by Pawel Szymanski who is the National Philharmonic Orchestra's Composer in Residence for the 2012/2013 season. This was a commissioned work dedicated to the memory of 'Luto'. This was a fine work of complex rhythmic structure and instrumental timbres. One would have needed to be familiar with Lutosławski's symphonies to fully appreciate the gestures of reminiscence.

We then heard Lutosławski's magnificent Third Symphony (1981-83), a true masterpiece of the modern 20th century repertoire and performed rather more often than many of his works. The Berlin Philharmonic with Sir Simon Rattle performed the work this year at the Proms in London.

The opening brass 'salvoes' had clearly been mirrored in the previous valedictory piece. Here was Lutosławski 's unique developed voice that seems to owe so little to the past. Antoni Wit conducted the Warsaw Philharmonic in a far more lively and committed manner than usual, both conductor and orchestra seemingly quite at home with Lutosławski's concept of 'limited aleatorism' whence the musicians play phrases or fragments in their own time. I was strongly reminded of the energy, diverse and incisive orchestral colours of Olivier Messiaen's Turangalila Symphony, although Lutosławski did not have a love narrative here as did Messiaen or share the French composer's obsession with birds and the sounds of the Orient.

At the period the Third Symphony was written Poland was labouring under Martial Law and if one realizes this the martial elements seem to have a clear reference although he would probably have denied that it had any such 'programme' of suffering, hope and resolution.

However as Thomas Mann showed in his great musical novel Dr. Faustus, a composer can subconsciously express profoundly the torture and suffering of his time without fully realizing what he is accomplishing. I feel one cannot listen to this work in a linear developmental fashion but see the work from above, laid out as it were in an instantaneous glance of the eye or rather ear, complete as a whole, a superb and beautiful oriental carpet containing a wonderful variety of colours and woven sound.

In the recent brilliant Jagiellonian Exhibition mounted in Warsaw at the Royal Castle and National Museum, I saw a large painting of the Passion of Christ brought from Torun and painted in 1470-80. All the sufferings of the Saviour were depicted at once in no particular chronological linear order which is the way one normally traverses the conventional Stations of the Cross in a church. In this panel one embarks on a sort of travel adventure, exploring this or that moment of Christ's familiar suffering not pictorially related in time but which finally accumulates to make an entire powerful Gestalt of his suffering. The picture is a type of what one might conveniently term a 'simultaneous painting'. This seemed absolutely analogous to such a piece of music as the Third Symphony by Lutosławski. One fixes and absorbs discrete details, complete passages and forms which create a final cumulative overwhelming effect upon completion.

|

| The seductive Anne-Sophie Mutter |

The mysterious, sensitive and bewitching creature that is the virtuoso violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter then took the stage to play the Partita for Violin and orchestra with Piano Obbligato (1984/88) written for her by Lutosławski. Unusually for an instrumentalist of her great artistic calibre she has a strong interest in performing contemporary classical works and many living composers have written pieces specifically for her (including Poland's greatest living composer Krzysztof Penderecki). We were requested not to applaud until the conclusion of the three works that made up the post interval section.

Then the Interludium for Orchestra (1989) which was a Pianissimo work of truly sublime sensitivity, a type of vibration of the soul that hypnotised me absolutely. Really one of the most remarkable orchestral works I have ever heard. Mutter stood by without playing throughout this work like some variety of statuesque musical Venus who had wandered out of Botticelli's Primavera, a discreet garland of exotic flowers ascending from the hem of her black gown. A unique tableau vivant to be sure...

Then to the remarkable Chain II (1984-85) also a vehicle for the expressive heart of Anne-Sophie Mutter, a later version dedicated to her by Lutosławski after he was deeply moved the first time he heard her perform it. The bloom of the sound of what I presume was one of her Stradivarius instruments was glorious. I think the very best I can do is quote her own words from her website concerning this work and what it means to her:

Chain II

Lutoslawski chose the word "chain" to describe a principle of composition, which he discovered in the eighties.

"For the last few years I have been working on a new musical form, in which two independent layers are put together. The sections inside these layers begin and end at different times. This is why the name "Chain" was chosen."

It is a technique, which allows differently formed sections in the violin and orchestra parts to work together in Chain II. This dialog for violin and orchestra is a work commissioned by Paul Sacher, who co-conducted the premiere performance with me on January 31, 1986 in Zurich. The piece has four movements beginning with an ad libitum section. The violin begins alone almost in the same cadence. The second section, a battuta, is in the form of a toccata which is a strong contrast to the more lyrical beginning. Particularly moving for me is the entangled ending, which reminds me of a passage from Don Quixote by Richard Strauss, namely Don Quixote’s death.

The slow ad libitum section is wonderful because the violin can express itself to the fullest. Also, it becomes very clear that one has more time for interpretation, because the conductor and soloist can decide when a new section should begin. The fourth movement has the character of finality. It concludes after a short ad libitum in a furious finale.

Witold Lutoslawski on Chain II:

"I composed the first version of the partita for violin and piano as a work commissioned by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra for Pinchas Zukerman and Marc Neikrug. It was performed for the first time by these artists in January, 1985, at a concert featuring my works and at which I conducted.

The new version for violin and orchestra (and piano obligato), which is presented in this version, was expressly written for Anne-Sophie Mutter and is also dedicated to her. I created this new version following the very strong impression that Anne-Sophie Mutter's performances of my Chain II left on me. Her extraordinary talent truly inspired my compositional efforts, and I hope to be able to write even more for her.

http://www.anne-sophie-mutter.de/index.php?L=1

http://www.anne-sophie-mutter.de/index.php?L=1

Speeches followed the tumultuous applause and standing ovation. She and Antoni Wit were presented with the medal of the Witold Lutosławski Association.

She was also given a statuette for her philanthropic charitable work for the Przyjaciel Fundacji Dom Muzyka Seniora - an organisation that provides assistance to elderly, retired musicians in Poland. Addressing the audience in German after the concert, she observed:

'Witold Lutosławski is a gift from God. It was 1985 when I first encountered his music, and it was a turning point in my life - he opened a window into the future. It was very fortunate. For me, Witold Lutosławski created the most perfect music.'

She was also given a statuette for her philanthropic charitable work for the Przyjaciel Fundacji Dom Muzyka Seniora - an organisation that provides assistance to elderly, retired musicians in Poland. Addressing the audience in German after the concert, she observed:

'Witold Lutosławski is a gift from God. It was 1985 when I first encountered his music, and it was a turning point in my life - he opened a window into the future. It was very fortunate. For me, Witold Lutosławski created the most perfect music.'

A marvellous although aurally demanding evening that has set me back on the wandering 'lawless' roads of my musical youth.

The eminent music critic Michael Cookson posts an interesting recent interview with Anne-Sophie Mutter in Manchester:

http://www.seenandheard-international.com/michael-cookson-interviews-anne-sophie-mutter-manchester-2012/