Sydney Symphony Orchestra - Warsaw - 29 November 2018

Sydney Symphony Orchestra

David Robertson conductor

Renaud Capuçon -violin

The Warsaw Filharmonia was absolutely packed for this concert. Hardly a spare seat in the entire auditorium and a buzz of anticipation enlivened the atmosphere. A rare sight. With temperatures at -5C during the day accompanied by jet lag it must have required great stamina and energy to perform.

|

| A painting of Ignacy Jan Paderewski by Edward Dwurnik (2018) Private Collection |

Paderewski

was extremely popular in Australia on his tours in the 1920s and loved the enthusiasm

of Australian audiences. This was also partly because of his friendship in

Europe with the famous soprano Dame Nellie Melba. Paderewski and his wife often

dined with her in Paris and Monte-Carlo.

The

Brisbane Courier described a Paderewski

concert at His Majesty's Theatre in April 1927

Paderewski,

the world famous pianist, was accorded a royal reception on Saturday night when

he gave the first of two concerts at His Majesty's Theatre. The house was

filled to overflowing and additional seats were arranged in tile stage and in

the pit usually occupied by the orchestra The ovation with which the pianist

was received continued for several seconds, and was repeated several times

during the evening. Included in the huge audience were the Mayor and Mayoress

of Brisbane, Alderman and Mrs. W. A. Jolly....

One

home of musical events in Brisbane was the Cremorne Theatre on the banks of the

Brisbane River. The great Polish pianist also performed there on his tour of

Australia and commented favourably on the musical discrimination of both Sydney

and Brisbane audiences. The newspaper described what an audience might

experience in this type of early Australian theatre during the capricious

summer weather

Open-air

entertainments are delightful on summer evenings in Brisbane, and the popular

‘Cremorne’ theatre, situated on the river bank, South Brisbane, facing the

south-east, and open to the cool breezes, is always a favourite resort. During

the cool evenings, and when the weather is threatening or unpropitious, the

popular theatre is converted into a huge canvas hall, and completely enclosed

in waterproof awnings and side screens which afford protection against

inclement weather.

(from The

Pocket Paderewski: The Beguiling Life of the Australian Concert Pianist Edward

Cahill Michael Moran, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne 2016)

Ignacy Jan

Paderewski - Overture

in E-flat major for orchestra (1884)

This rather recently discovered work made a suitably festive opening to this rare visit of the SSO to Warsaw in Poland. There has been somewhat of a resurgence of what in the past was termed Paddymania (wild, almost irrational, enthusiasm worldwide for this artist) in Poland during the 100th independence anniversary celebrations.

The orchestra

gave it a suitably robust and lively performance appropriate for its

festive 'not too serious' character, invested no doubt with the consciousness

and excitement they were playing in Poland, the composer's birthplace.

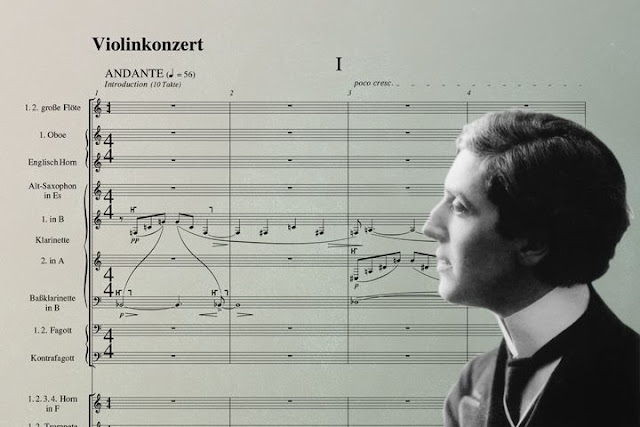

Alban Berg - Violin Concerto (1935) 'To the memory of an Angel'

And so the Viennese section of the evening began. The composer of this challenging work wished to meld conventional diatonicism (harmony) with dodecophany (his teacher Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone compositions associated with the Second Viennese School).

I cannot possibly improve on this fascinating article by the great conductor Otto Klemperer which appeared in the Viennese newspaper Wiener Tag on October 21, 1936, ten months after Alban Berg's death. At that time he was Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic:

"When I was invited by the management of the Vienna Philharmonic to conduct two concerts during the present season, they expressed the wish that I should perform a novelty, suggesting Alban Berg's Lulu Suite. I had already conducted it with considerable success in America... But as the Suite had been previously performed in Vienna, it seemed to me that the laudable decision of this famous orchestra to present a commemorative performance for Berg was such a noble and precious testament of esteem that it would be more suitable to perform the master's last work, not yet heard in Vienna - his Violin Concerto... which belongs here, to Vienna, to Austria, where it was created and with which it is intimately bound up... I cancelled two European concerts to give myself the necessary time for rehearsals. I also cut down on my social engagements in Los Angeles, then I began my study of Berg's score.

"At that time I was physically in Los Angeles while in spirit I was in Vienna, in the Hohe Warte or Hietzing, and in Carinthia... Berg lived in Hietzing… in the Trautmannsdorfstrasse. The last time I was with him there, on a fine summer afternoon in 1935, and he had played his opera Lulu to me, he had not yet written the Violin Concerto. Who could have imagined that this work would be his own requiem, as well as a requiem for... the young Manon Gropius [daughter of Gustav Mahler's widow, Alma, and the architect Walter Gropius], with her dreamlike beauty... whom I had met in Mahler's house in the Hohe Warte. I could see her before my very eyes, pale and quiet, in that famous room with its walls formed by the glass cabinets in which Mahler's manuscripts were kept... And then I saw Berg, who was just as much at home there as in his own house and in the Carinthian countryside... where he heard the folk tune, a Ländler ["Ein Vogel auf'm Zwetschgenbaum" - A Bird in the Plum Tree], with which he associated the fresh, naive manner of this young girl.

The tune was woven into the score of the Violin Concerto and concludes on a tremendous climax. At this high point of the work I felt, death makes its cruelest appearance, but death never means the end. The second movement begins with the J. S. Bach chorale Es ist genug: 'It is enough! Lord, if it please Thee, my Jesus, come! World, good night. I go to the heavenly house, with a heart full of joy. My sorrows remain below.' The variations on this chorale, the sounds that emanate from the violin, that bring into being a completely new world for the instrument, the way in which at the conclusion the music seems to span the cosmos, from the lowest depths to the sublime heights, all of this I came to experience in Los Angeles… Now, in a few days' time, Alban Berg's [Violin Concerto], played by the finest orchestra of Europe, the Vienna Philharmonic, will be given its performance. I look forward to that moment with humility and joy." (courtesy of Herbert Glass and the LA PHIL)

The work is in two movements, each divided into two sections:

Andante (Prelude)Allegretto (Scherzo)

Allegro (Cadenza)

Adagio (Chorale Variations)

The first two sections are meant to represent life, the last two death and transfiguration. The conductor David Robertson has an enviable reputation for conducting modern classical orchestral music and his authority over this dense, inconsistent and complex work was clear. The orchestra were confident in dealing with Berg's curious and unusual amalgam of tonality and serialism. Tremendous demands are made on the soloist in this work. From where I was seated in the Parter, I felt the orchestra tended to overwhelm the soloist on occasion and he disappeared under a welter of serial writing.

Although Renaud Capuçon is a brilliant violinist and coped formidably with the technical demands, I felt he was not temperamentally or perhaps even tonally 'at home' in this work or this atonal palette of sound and structure. I find him far more comfortable with harmonic works that have a lyrical singing melodic line, classical structure and are less aggressive and violent. Of course I have heard him mainly in chamber music of small forces with all the greatest instrumental players at renowned European music festivals, a form of music at which he excels with his younger brother, the extremely charismatic and virtuoso cellist Gautier Capuçon.

Gustav Mahler - Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp

Minor (1901-2)

This vast work is a symphony is like no other in my experience and lasts an astonishing seventy minutes or so. To present an integrated convincing performance is an Everest to climb. The soloists need to be outstanding. It is in five movements grouped into three major sections which can be regarded the truest structure of the work. The musical fabric has an ungraspable, elusive wildness about it, full of anger and rage (but not only that) against the inescapable dark fact of death. I felt in the first movement (and not only here) that the orchestra and conductor did not organically feel the refined lilt and charm in the rhythm of the Viennese waltz, that intangible physical predilection of dance that infuses this symphony, becoming less innocent as time passes. This rhythm cannot be notated but must be felt from within by conductor and orchestra. Sir Simon Rattle speaks of listening to a piano roll of Mahler's recording of the first movement which taught him much about this rhythmic aspect of the work.

The pivotal obbligato horn section in the the middle movement (written as a separate part) was quite brilliant and securely performed by the player in his dialogue with the strings. However although satisfying in many respects, overall in this performance, I felt a sense of excitable striving for effect resulting in insufficient clarity in the dynamic variation, orchestral colour, meaningful dynamic tensions and relaxations, counterpoint and phrasing that breathed naturally with musical meaning. I was hoping for a more subtle and detailed performance perhaps, less driven by the excitement of the moment and the unalloyed impetus of this magnificent orchestral writing.

I hoped we might be emotionally uplifted by the Adagietto (not as slow as Adagio) which of course is the most famous movement of the symphony and was performed long before the symphony was in its entirety. Perhaps it is the only movement in a symphony whose tempo has been influenced by its use in a film and become a sort of standard of appreciation. However remember Visconti used the music in Death in Venice together with the augmentation of seductive, insidious imagery and the spell-binding story of Thomas Mann's novella in order to move us so effectively. The slower tempo modification in the film was justified I felt.

Mahler wrote a love poem to his wife Alma represented by

this movement and mentioned in a letter she wrote to the great Dutch

conductor Willem Mengelberg

Wie ich Dich liebe, Du

meine Sonne,

ich kann mit Worten Dir's nicht sagen.

Nur meine Sehnsucht kann ich Dir klagen

und meine Liebe, meine Wonne!

ich kann mit Worten Dir's nicht sagen.

Nur meine Sehnsucht kann ich Dir klagen

und meine Liebe, meine Wonne!

How much I love you, you my sun,

I cannot tell you that with words.

I can only lament to you my longing

and my love, my bliss!

I cannot tell you that with words.

I can only lament to you my longing

and my love, my bliss!

I felt this sensitive, passionate yearning and tenderness was not sufficiently nuanced by Robertson or sensitively enough expressed by the orchestra. Phrasing could have been more ardent and the texture more subtle. I fully realize we do not want to drown in sentimentality but we do not want to err on the side of cooler, mundane and straightforward passions, less lovelorn and failing to express the great compensation of love over the yawning abyss of death. Another dimension to this complex redeeming emotion, the exaltation of love, is expressed in the last movement which was broadly accomplished with sweeping energy, line, drive and commitment by both orchestra and conductor.

The audience adored this full blooded performance and gave it a tempestuous standing ovation with much cheering, so who am I to criticize too deeply?

As an encore in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Leonard Bernstein, the orchestra chose to play the immensely popular overture to his operetta Candide. I felt the orchestra and particularly the American conductor David Robertson had an instinctive sympathy with this genre of music and performed it with tremendous verve and American showboating panache.

Comments

Post a Comment