London Symphony Orchestra and Sir Simon Rattle - Wrocław - 16 January 2019

|

| Narodowe Forum Muzyki (NFM) Wrocław, Poland |

Not surprisingly, Polish concert

audiences after years of musical drought continue to yearn for and hugely

anticipate performances by great international orchestras and conductors. Such

visits to the country are still not common although increasing as time passes

and Poland slowly takes its place once more in the European musical firmament. Understandably then, the acoustically

magnificent and architecturally striking NFM (Narodowy Forum Muzyki) in Wrocław was sold out for the London

Symphony Orchestra conducted by their new musical director Sir Simon Rattle. The

programme was an imaginative pairing of works by Béla Bartók and Anton

Bruckner.

The commissioning of the Music

for Strings, Percussion and Celesta by Bartók reflects a change in society. No longer the nobility and aristocracy

enabling the composition of a great musical work. On this occasion corporate

wealth was the facilitator. In 1934, the Swiss conductor Paul Sacher married Maja Stehlin. She was

a widow who had inherited the immense fortune of the pharmaceutical giant Roche. Sacher was able to indulge his musical passions and spent lavishly on his obsessive interest in new music. Some time

before, in 1926, Sacher had founded the Basle Chamber Orchestra, an ensemble that

performed new compositions and almost forgotten music from the pre-classical

period. In order to adequately commemorate the 10th anniversary of the

orchestra, Sacher commissioned a new work from the then revolutionary contemporary composer

Béla Bartók. The result was a masterpiece, rather simply and unimaginatively

entitled Music for Strings, Percussion

and Celesta.

The work is divided into four movements.

By some shocking coincidence it was a day of mourning over a terrible tragedy in

Poland that had occurred two days before - this land of valiant resistance to

oppression, a country still haltingly embracing democratic freedoms. The

powerful liberal voice of the much loved Mayor of Gdańsk, Paweł Adamowicz

(20 years in office), was silenced with his barbaric assassination, stabbed at

an annual charity event by a 'madman'.

'I am a European, so my nature is to be open,' Adamowicz told the English Guardian newspaper in 2016. 'Gdańsk is a port and must always be a refuge from the sea.'

The event was dedicated, now it seems with the grimmest of ironies, to saving the lives of innocent children.

After a minute's silence in darkness, the fugue of the first movement Andante tranquillo began to unfold. The sombre mood evoked seemed almost metaphysically appropriate to the circumstances of this national tragedy.

'I am a European, so my nature is to be open,' Adamowicz told the English Guardian newspaper in 2016. 'Gdańsk is a port and must always be a refuge from the sea.'

After a minute's silence in darkness, the fugue of the first movement Andante tranquillo began to unfold. The sombre mood evoked seemed almost metaphysically appropriate to the circumstances of this national tragedy.

|

| Béla Bartók in the 1930s |

The LSO under Sir Simon Rattle eloquently

brought out the melancholic, restless moaning and lamentation of the fugal theme

and the rise in tension as the melody progressed to its climax only to fall

back in retrograde motion to the piano beginning. The orchestration of this work is unique as is the placement of the instruments. The second movement Allegro

was a passionate and agitated account of rural Hungarian violin music with

fine percussive playing from the pianist. One cannot help but feel that the intense emotional

agitation of the musical idea here (pizzicato strings, frighteningly violent tympani

strokes, turbulent piano passages) is a presage of the devastating war that was just over the

horizon. Rattle accomplished this spiritual unease with atmospheric rhythmic contortions.

The remarkable and psychically disturbing

third movement begins with a notoriously famous xylophone solo. One note, becoming faster and faster before slowing.

It was here I truly noticed the alluring transparency of this orchestra and the

crystal clarity of the percussion. In some interpretations (Fritz Reiner and

the Chicago Symphony) a definite Japanese Kabuki theatre or even Buddhist

temple feel is given to this movement by the percussion which was not so

obvious with the LSO. Fragments of the fugue appear disconcertingly as the

movement progresses punctuated by the xylophone and watercolor washes of sound

from the harp, piano and celeste. In possibly fanciful hindsight one cannot

help feeling once again the tragic premonition of a conflagration. The refined lightness of

the LSO strings gave a gossamer halo around the penumbra of sound.

|

| London Symphony Orchestra and Sir Simon Rattle [all photos by Sławek Przerwa] |

|

| Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times |

In the finale Rattle brought his

intense feeling for rhythm to dispel these dark clouds and introspection to

embrace the living breath in Hungarian peasant dances in sunlit village fields. We

hear zithers, cimbaloms and fiddles. Humorously Bartók quotes a wrong-note

parody of the nonsense song Charlie Chaplin sings in Modern Times. The film had been released shortly before he began the

composition. The dense orchestral writing continues to grow until the energetic

dance rhythms resume and a return of the theme and triumphant close. Rattle

and the LSO accomplished this arc of rhythmic and orchestral complexity with

great panache and élan.

|

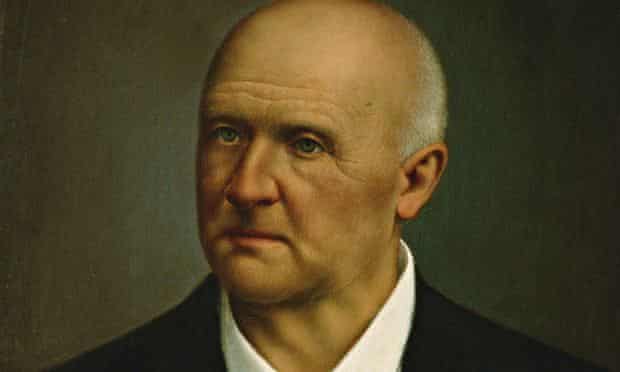

| Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) |

After the interval the 6th

Symphony in A major by Anton Bruckner. The effect was a disconcerting journey back in

time from the ultra modern sound world of Bartók (1936), a feeling of being forcibly returned to the nineteenth

century world of this symphony (1879-81). Bruckner symphonies always create some

controversy of opinion as does the personality of the composer. He seemed to have rather a morbid preoccupation with death. In 1888 the remains of Beethoven and Schubert were moved to the Central Cemetery in Vienna. Eyewitness accounts relate that Bruckner rushed forward and 'fingered and kissed the skulls of both composers.'

Be that as it may, connoisseurs of his music all agree on the greatness of this 6th symphony. It is full of dynamism, rhythmic invention and refinement as well as utilizing an alluring range of orchestral colours. Sir Simon Rattle and the LSO brought an unaccustomed lightness and elegance (dare I say) to the string sound in comparison to the deeper mahogany timbre of German orchestras when they approach Bruckner in a vein if deepest seriousness. I found the opening Majestoso movement (note not termed Maestoso) both dramatic and immensely dynamic. The movement is crammed with unexpected harmonic modulations and 'military' associations bordering on film music. The way Bruckner controls the dynamic expansion to forte-fortissimo with powerful tympani creates and atmosphere of monumental musical theatre.

Be that as it may, connoisseurs of his music all agree on the greatness of this 6th symphony. It is full of dynamism, rhythmic invention and refinement as well as utilizing an alluring range of orchestral colours. Sir Simon Rattle and the LSO brought an unaccustomed lightness and elegance (dare I say) to the string sound in comparison to the deeper mahogany timbre of German orchestras when they approach Bruckner in a vein if deepest seriousness. I found the opening Majestoso movement (note not termed Maestoso) both dramatic and immensely dynamic. The movement is crammed with unexpected harmonic modulations and 'military' associations bordering on film music. The way Bruckner controls the dynamic expansion to forte-fortissimo with powerful tympani creates and atmosphere of monumental musical theatre.

The Adagio: Sehr feierlich second movement is the one of Bruckner’s most

heart-breaking slow movements. The transformation of the yearning opening lament of the

oboe brings one close to tears. The slow tempo adopted in this movement by Sergiu

Celibidache in the 1991 recording he made with the Münchner

Philharmoniker is so profoundly moving and to my mind, replete with an expression

of unrequited love or a death lament. I felt Sir Simon did not explore the depths of this supplicant

movement to anything like the same degree.

This was not true of his approach to the

unusually slow Scherzo: Nicht schnell — Trio: Langsam to which he imparted strong rhythmic 'military'

brass then lyric string energy yet with a deep, disturbing constant toiling of

basses and cellos rumbling quite physically through our diaphragms. There are such contrasts of orchestral textures and layers of harmony

in this movement!

The Finale:

Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell is a triumphal close to the symphony but one

that leaves a strangely ambiguous atmosphere despite so many of the symphonic threads

being brought together in the massive declamatory coda. The LSO under Rattle, with the lighter string timbre and more lyrical approach to this symphony, brought it to an emotionally satisfying

rather than Brucknerian monumental conclusion of hewn granite.

As an encore the LSO and Sir Simon gave us some of

the most joyful, enthusiastic, energetic and infectiously rhythmic account of Gorale

Dances by Moniuszko I have ever heard, even including dare I say, Polish orchestras

and conductors. In this 200th anniversary year of the birth of Stanisław Moniuszko, his vibrant and vital account full of rustic verve brought the

entire audience cheering to their feet at the conclusion.

What a joyful conclusion to a day that began

in such an heavy atmosphere of national tragedy and horror. Was the magic of music acting as a variety of emotional resuscitation and spiritual regeneration?

Comments

Post a Comment