Yu Kosuge / Paul Goodwin - National Philharmonic Orchestra, Warsaw - 25 January 2019

Snow was falling in Warsaw, the night punishingly cold. The ground was covered in ice and slush thoughtlessly thrown up from the tarmac by black Mercedes speeding past. How pleasant to arrive for a concert with time in hand and able to look forward to a warming cup of green tea and the best Napoleonka in the world. This traditional indulgence of mine consists of a small square of deliciously thick Polish vanilla custard cream sandwiched between two layers of puff pastry and dusted with icing sugar. Also known as a kremówka, the combination with green tea is a perfect relaxed emotional preparation for a winter concert in the warm Philharmonic concert hall. I have given in to this sensual, indulgent ritual for years.

The concert was an attractive programme of classical symphonies and a Mozart piano concerto with the the gifted and acclaimed young Japanese pianist Yu Kosuge. She has played with all the major Japanese orchestras and worked with leading European orchestras under great conductors such as Seiji Ozawa and Lawrence Foster. This was her debut with the Warsaw Philharmonic. The orchestra played under the distinguished guest conductor Paul Goodwin.

The concert opened with the Symphony in D major Wq 183/1 by one of my favourite classical transitional composers (Baroque to Classical), Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. In the second half of the Eighteenth Century, C.P.E. Bach, not his father who was by then thought to be old fashioned, was considered to be the 'Great Bach.' Mozart said of him 'Bach is the father, we are the children'. He was the second eldest and certainly the most famous of Johann Sebastian's sons. He was one of the first composers to unashamedly introduce personal emotion and self-expression into music. C.P.E. Bach was therefore regarded as the foremost champion of the Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) movement of the late Eighteenth Century. Evolving from the Baroque this period is seen as a transition between J.S. Bach, Handel, and Telemann, and the compositions of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. He wrote fine keyboard concertos and sontatas, symphonies, chamber music and choral works.

He also wrote an important treatise whilst teaching in Berlin which I have quoted many times in my reviews: Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments). This is the most important Eighteenth Century German language source material on this subject. He was employed at the Prussian court from around 1740 but was never fully appreciated by Frederick the Great, despite the king's gifts as an instrumentalist and composer.

The concert was an attractive programme of classical symphonies and a Mozart piano concerto with the the gifted and acclaimed young Japanese pianist Yu Kosuge. She has played with all the major Japanese orchestras and worked with leading European orchestras under great conductors such as Seiji Ozawa and Lawrence Foster. This was her debut with the Warsaw Philharmonic. The orchestra played under the distinguished guest conductor Paul Goodwin.

The concert opened with the Symphony in D major Wq 183/1 by one of my favourite classical transitional composers (Baroque to Classical), Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. In the second half of the Eighteenth Century, C.P.E. Bach, not his father who was by then thought to be old fashioned, was considered to be the 'Great Bach.' Mozart said of him 'Bach is the father, we are the children'. He was the second eldest and certainly the most famous of Johann Sebastian's sons. He was one of the first composers to unashamedly introduce personal emotion and self-expression into music. C.P.E. Bach was therefore regarded as the foremost champion of the Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) movement of the late Eighteenth Century. Evolving from the Baroque this period is seen as a transition between J.S. Bach, Handel, and Telemann, and the compositions of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. He wrote fine keyboard concertos and sontatas, symphonies, chamber music and choral works.

He also wrote an important treatise whilst teaching in Berlin which I have quoted many times in my reviews: Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments). This is the most important Eighteenth Century German language source material on this subject. He was employed at the Prussian court from around 1740 but was never fully appreciated by Frederick the Great, despite the king's gifts as an instrumentalist and composer.

In this D major symphony I find his abrupt changes of mood, daring harmonies, and unpredictability terribly exciting. These were bold and adventurous musical experiments in ways not fully understood at the time but are now. This was music that 'speaks to the heart' and 'awakens the passions.' J.F. Reichardt, who was a distinguished music critic during the Eighteenth Century, wrote of C.P.E. Bach's 'original and audacious progression of ideas and the great variety and novelty in the forms and modulations' of symphonies such as this one in D major.

In this performance I felt most of the musicians of the Warsaw Philharmonic (with the possible exception of the double bass players), despite the most energetic and enthusiastic, even passionate, exertions of the eminent conductor Paul Goodwin, were unable to respond fully to music they did not deeply understand, perhaps had performed rarely or possibly were complacent about. I missed many important elements of Baroque performance practice. Paul Goodwin is a fine oboist and spent many years as the associate conductor of Christopher Hogwood's Academy of Ancient Music and principal guest conductor of the English Chamber Orchestra.

Yet the extreme and sudden shifting emotional contrasts seemed tantalizingly out of their reach, despite their musical commitment. C.P.E. Bach requires an expressive appreciation and understanding of the style galant or empfindamer Stil ('sensitive style') as it might be known. Characterized by rapidly fluctuating sentiments, nuances, rather extreme variation in rhythm and dynamics, short phrasing, in essence the thrill of an unexpected harmonic transition. The contrast with the music of his father could not be greater. This feeling of 'frontier excitement' was rather absent for me in this performance.

Yet the extreme and sudden shifting emotional contrasts seemed tantalizingly out of their reach, despite their musical commitment. C.P.E. Bach requires an expressive appreciation and understanding of the style galant or empfindamer Stil ('sensitive style') as it might be known. Characterized by rapidly fluctuating sentiments, nuances, rather extreme variation in rhythm and dynamics, short phrasing, in essence the thrill of an unexpected harmonic transition. The contrast with the music of his father could not be greater. This feeling of 'frontier excitement' was rather absent for me in this performance.

The orchestra were then joined by the gifted young Japanese pianist Yu Kosuge f0r the popular Mozart Piano Concerto No 21 in C major KV 467 (1785). Who now remembers that lyrical film Elvira Madigan (1967) that has given its name to the concerto?

The film was released while I was at university in the late 1960s and had an extraordinary impact at the time. The superbly aesthetic cinematography, the lyrical summer landscape of Sweden and the radiant leading actors of this tragic legendary tale affected everyone. A handsome cavalry officer and a beautiful slackline walker from the circus elope, escaping reality into the world of dreams, the world of their love, until the sword of Damocles inevitably falls. One never for a moment wishes to deny them these supreme pleasures although the irrationality of the decision is clear.

This is the first and only time to my knowledge that music is not used simply as atmospheric furnishing but plays a supremely predominant role in emotionally painting the inexpressible, those feelings of love that lie beyond the power of language and even image to engage. There is comparatively little dialogue between the lovers. Music in films today simply enhances, does not play a radical role in the evolution of the plot as it does here. The internal romantic life of the doomed lovers is contained within the soundtrack, the glorious Andante of the Mozart piano concerto in C major, that together with the birdsong of the natural landscape through which they flee.

|

| The real Swedish nobleman and cavalry officer Sixten Sparre and the circus slackline walker Elvira Madigan (her stage name). However the grim reality behind this poetic film was very different. |

The celebrated Hungarian-Swiss pianist Geza Anda with the Camerata Academica of Salzburg Mozarteum contributed the superb soundtrack. It would be as well that all young performers of this concerto see the film and listen closely to broaden their associative emotional and expressive scope. Accelerate the imagination and go a dimension deeper!

The year 1785 was an extraordinarily busy time for Mozart. His father Leopold wrote to his sister Nannerl of this period: 'Every day there are concerts; and the whole time is given up to teaching, music, composing and so forth...It is impossible for me to describe the rush and the bustle.' The concerto evidences no sign of these distractions nor of the astonishing contrast to the passionate existential despair we find at the heart of the the D minor concerto K 466 finished only shortly before.

Yu Kosuge played the opening Allegro maestoso movement with great conviction, musicality, finely honed finger technique, refined touch and luminous tone. She maintained exceptional visual contact with members of the orchestra and the conductor. The orchestra were more familiar with this Mozart than the C.P.E. Bach and the conductor Paul Goodwin was clearly intimately familiar with the Mozartian historically informed classical style and idiom. However with the rather fast tempo they adopted, as the movement progressed, I did not feel the 'Olympian grandeur' of the opening in terms of expressive phrasing or truly heartfelt emotion. It became rather too pianistically focused. The expressive soul of Mozart must be permitted time to speak and the conversational musical discourse given air to breathe and communicate emotion. Mozart piano concertos are rather like mini operas and often contain fragments of sublimated arias. The important feeling of spontaneity and improvisation was missing for me.

Kosuge performed the sublime Andante with a degree of sentiment that was certainly melodically very moving in its emotional weight. Her cantabile tone and legato phrasing in this beautiful movement was poignant. Mozart composed the melodic line to be rather bare and open which would have permitted his famed improvisations free reign. This once popular, historically accurate activity should be resumed in performances. Why not today?

The Allegro vivace assai, really a type of joyful opera buffa, was replete with energy and exceptionally refined with her exciting virtuosic pianistic abilities on display. But again I felt an expressive breathlessness and missed that artful Viennese Gemütlichkeit and charming conversational tone, the vocal nature of many musical phrases, musical question and answer thrown between instrumental groups and the piano. In Mozart expressiveness lies in the magic of the phrasing and the infinitesimal hesitations of conversational musical speech as the music tenses and relaxes. Overall I was hoping for a more individual voice in the concerto. An enjoyable and very fine performance certainly but my heart yearned for more felt expressiveness.

As an encore Kosuge played the Chopin A-flat major Étude from the Op. 25 set which was enthusiastically received by the Polish audience.

As an encore Kosuge played the Chopin A-flat major Étude from the Op. 25 set which was enthusiastically received by the Polish audience.

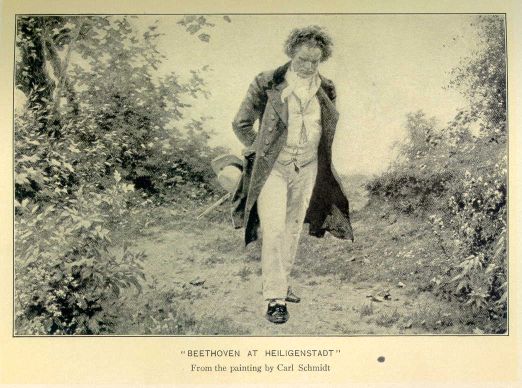

After the interval the 2nd Symphony of Beethoven in D major Op.36 (1802). One of the mysteries of Beethoven's strength of character is how he managed with the horror of increasing deafness to produce a work as cheerful and blithe as this symphony. The initial sketches are from 1802, the period he spent in rural Heiligenstadt, his cottage with a pictuesque view of the Danube. The pathologist Dr. Johann Adam Schmidt had advised a break from Vienna to the countryside. Later the surroundings would become the likely setting for his Pastoral symphony. Deafness would seriously descend in 1803, the year of the premiere of this symphony in Vienna. His tragic utterance within the unforgettable Heiligenstadt Testament dates from this time.

My misfortune is doubly painful to me because I am bound to be misunderstood; for me there can be no relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas. I must live almost alone, like one who has been banished; I can mix with society only as much as true necessity demands. If I approach near to people a hot terror seizes upon me, and I fear being exposed to the danger that my condition might be noticed. Thus it has been during the last six months which I have spent in the country. By ordering me to spare my hearing as much as possible, my intelligent doctor almost fell in with my own present frame of mind, though sometimes I ran counter to it by yielding to my desire for companionship. But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone standing next to me heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me almost to despair; a little more of that and I would have ended my life - it was only my art that held me back.

(A passage from the Testament © Translation John V. Gilbert)

Paul Goodwin clearly loves this work and brought an infectious verve and energy to the performance. The orchestra responded relatively well to his driving and vital momentum. In the first movement Adagio molto - Allegro con brio his precipitate fortissimo opening was a terrific explosion of Beethovenian sound, 'enough to lift the hat off one's head' as Schumann is reported to have once observed of the composer's music. The long Adagio introduction was beautifully sustained and the Allegro packed with nervous excitement. The difficult to establish Larghetto tempo was carefully chosen by Goodwin and was eloquent in its graciousness. Beethoven replaced the customary Haydnesque Minuet with a exuberant and playful Scherzo Allegro. Goodwin and the orchestra communicated these light-hearted, sprightly emotions very well. The final fourth movement Allegro molto abounds in musical jokes and is full of wit of a particularly robust Beethovenian kind. Goodwin understood the nature of these humorous syncopations and the orchestra followed his energetic, inspirational style with increasing commitment.

A Warsaw concert of accessible and popular music that warmly and affectionately distracted one from the icy blasts that met one on opening the heavy Philharmonic doors to the snow-drifted, unwelcoming winter street.

* * * * * *

Some exciting and imaginative news concerning Yu Kosuge from Presto Classical:

Celebrated Japanese pianist Yu Kosuge embarks on an exciting project: four releases inspired by the Greek concept of the four elements, Water, Fire, Air, Earth. Many composers have been drawn to the properties of these elements when seeking inspiration for their music, but Kosuge’s theme goes deeper, dating back to her successful Beethoven cycle: “When you understand that Shakespeare’s plays, read ardently by Beethoven, refer to Greek mythology, or that Beethoven himself composed some works based on the Prometheus myth, you would know that an artist who is searching for human nature would surely look to Greek mythology or philosophy...”

In Water, Yu Kosuge interprets a rich array of repertoire, from Liszt and Wagner to acclaimed contemporary composer Dai Fujikura. The ‘barcarolle’ takes its rocking rhythms from the motion of a boat: we hear examples by Chopin and Fauré, as well as Venetian Gondola ‘Songs Without Words’ by Mendelssohn.

Comments

Post a Comment