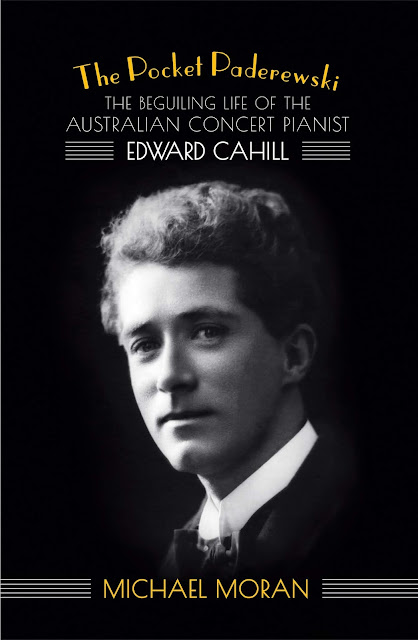

The Pocket Paderewski : The Beguiling Life of the Australian Concert Pianist Edward Cahill

In light of the enthusiasm for the new fashion exhibition Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams which opened at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London on 2 February 2019, I thought I might mention my recently published biography of the concert pianist and Chopin 'specialist' Edward Cahill (1875-1975). Also relevant is the recently published and highly popular and entertaining The Quest for Queen Mary by James Pope-Hennessy (Hugo Vickers ed.) Hodder London 2018. Both the exhibition and the book deal with the very same society in which my great uncle moved as a celebrity. As Pope-Hennessy points out, a largely forgotten generation today.

Apart from time spent giving the first recitals of Chopin in 1919 to Maharajahs in India and the King of Siam, he gave recitals in London, Paris and the French Riviera during its golden age. Under the patronage of his supporter Dame Nellie Melba, for a long period of his life he befriended and entertained members of this same dazzling English society that patronized Dior during the glamorous 1920s and 1930s in London and later after WW II in Paris. Nancy Mitford engagingly writes of this generation in The Pursuit of Love (London 1945)

Apart from time spent giving the first recitals of Chopin in 1919 to Maharajahs in India and the King of Siam, he gave recitals in London, Paris and the French Riviera during its golden age. Under the patronage of his supporter Dame Nellie Melba, for a long period of his life he befriended and entertained members of this same dazzling English society that patronized Dior during the glamorous 1920s and 1930s in London and later after WW II in Paris. Nancy Mitford engagingly writes of this generation in The Pursuit of Love (London 1945)

‘It’s rather sad,’ she said one day, ‘to belong, as we do, to a lost generation. I’m sure in history the two wars will count as one war and that we shall be squashed out of it altogether, and people will forget we ever existed. We might just as well never have lived at all. I do think it’s a shame.’

The biography is also a portrait, perhaps even a resuscitation, of this glamorous largely forgotten world as well as his extraordinarily colourful life, performing privately for Queen Mary, Queen Ena of Spain and the Windsors. He was a close friend of Wallis Simpson, dined and gave concerts at Boulevard Suchet in Paris often and harboured a surprisingly positive opinion of her character, quite at variance with the current view. He played for Princess Beatrice, (herself a fine pianist full of respect for Polish history) Lady Diana Cooper and many members of the British and French aristocracy in London, Paris and the French Riviera. He just happened to be my great-uncle.

|

| Edward Cahill seated in the front row on the left of Princess Alice at a private Mayfair piano recital at the home of the Dowager Lady Swathling 1934 |

He took lessons from Alfred Cortot in Cannes and Leonie Gombrich in Vienna, a sometime assistant of the great Polish pedagogue Theodor Leschetizky (Paderewski himself was a pupil) and mother of the great art historian Ernst Gombrich. He was known by the nickname The Pocket Paderewski thanks to his brilliant performances of Chopin but small stature and small hands. Yet neither Liszt nor Chopin posed technical execution problems for this remarkable man.

He had close connections with Poland, especially during the war years he spent in Switzerland giving many charity concerts for interned Polish troops. At this time he also walked the shores of Lake Geneva at Clarens discussing music with the great German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler.

His performances of Chopin have been highly praised by the Narodowy Instytut Fryderyka Chopina (The National Fryderyk Chopin Institute). For my biography, the pianists Leslie Howard and Piers Lane glowingly reviewed his preserved recordings as well as the distinguished Chopin performance critic James Methuen-Campbell. Just before his death in retirement in Monaco in 1975, 'Uncle Eddie' asked me haltingly to visit Poland and scatter his ashes at Chopin's birthplace at Żelazowa Wola, some 50 kms from the capital, Warsaw.

His performances of Chopin have been highly praised by the Narodowy Instytut Fryderyka Chopina (The National Fryderyk Chopin Institute). For my biography, the pianists Leslie Howard and Piers Lane glowingly reviewed his preserved recordings as well as the distinguished Chopin performance critic James Methuen-Campbell. Just before his death in retirement in Monaco in 1975, 'Uncle Eddie' asked me haltingly to visit Poland and scatter his ashes at Chopin's birthplace at Żelazowa Wola, some 50 kms from the capital, Warsaw.

* * * *

* Christmas 1940 was fast approaching for six thousand Polish officers and men interned in Switzerland. Snow and ice lay heavy on the ground. When in the midsummer of 1940 General Guderian’s Panzer divisions had pinned the French 45th Army Corps commanded by General Darius Daille against the Swiss frontier, the Swiss Federal Council rapidly granted refuge to the beleaguered French and Polish troops who had put up fierce resistance. The 45th Army Corps included some twelve thousand men of the Polish 2nd Rifle Division (2DSP Dywizja Strzelców Pieszych under General Prugar Ketling). They were among the valiant Poles who had joined the French to continue the fight for their homeland after the brutal German conquest of their country.

Unlike the French soldiers who were sent home in January 1941,

the Poles now found themselves homeless. The Polish state had once

again been erased from the map of Europe. Under international

law, the Swiss were now forced to finance their detention. To

facilitate this and simultaneously defuse political tension with Nazi

Germany (which had planned to invade Switzerland in Operation

Tannenbaum prior to the outbreak of war) a Polish mass detention

camp housing some six thousand men was established near the

picturesque medieval village of Büren an der Aare near Berne. It

was completed by the winter of 1940. Up to that time the Poles had

been billeted in scattered villages where they had become rather

too popular with the female population in the absence of Swiss

men gamely manning the frontiers and fortresses.

Their abrupt imprisonment at Büren led the Poles to suspect the

Swiss were acting on German instructions. Morale fell. The Swiss

tightened discipline. Anger erupted into revolt in December 1940.

Shots were fired and a number of Polish soldiers were wounded.

Following the revolt, the Poles were permitted to work for the

princely sum of one franc per day in field, forest and factory,

producing badly needed food. The results of this work more than

repaid the costs of their internment, to the great satisfaction of the

Nazi-encircled Swiss.

* * *

The cold on 15th December 1940 was Siberian in its intensity.*

The new arrivals at the little village station of Büren had crossed

the grey winter-wasted plains at the foot of the first range of the

Jura mountains by train. Swiss families of soldiers billeted in the

village were overjoyed to see their loved ones and thronged the

platform. However, among the passengers were a number of

Polish internees who descended from the train under watchful

eyes, their heads covered by forage caps like common prisoners. They were forbidden to acknowledge any civilians who had come to gawp. They saw no-one, watched nothing except

the little train returning to civilisation on its meandering course

and disappearing into the distance. They watched as one might

watch a ship slowly pass over the horizon with no hope of return. In the streets of the old town above the great medieval covered wooden bridge that spanned the River Aare, their comrades

sauntered in the village streets in small groups dressed warmly

in heavy brown overcoats and Basque berets. They vaguely

gazed into the windows of the Gothic-fronted boutiques, windows already too familiar and jammed with naive and rarely

changed arrangements of fashion and antiques.

This Sunday was unlike any other. Today the celebrated Australian pianist Edward Cahill would give a concert in the 13th

century Evangelical Reform church in the village. This was a rare

gift of God for such innate musicians as the Poles. Well before

the appointed time, the church was filled to bursting with men

sitting erect, wearing sombre expressions on faces weathered to

the colour of Spanish leather. Officials brusquely turned back

any civilians who tried to enter. The same veto applied to any

journalist from Berne who lacked official authorisation to attend

the concert. Polish and Swiss officers sat in the gallery while the

soldiers sat closely packed around the grand piano placed in the

centre of the choir. Then, Edward Cahill, who is small, slender

and quick had to thread his way through the rows of soldiers

to get to his instrument. He began with two impromptus by

Schubert followed by the famous Minuet in G by Paderewski. He

gave such an exquisite interpretation a tremor passed through

the audience.

The first notes of the Chopin ‘Heroic’ polonaise reverberated

through the church. Edward played works by the Polish master for more than an hour. Many present had never known a

more moving moment in their lives, occurring as it did in the

middle of a bloody conflict and desperate dispossession. In the

darkened church an immense atmosphere of self-communion or

meditation descended over the assembled refugees, the magnificent white hair of Edward Cahill seeming to softly glow above

the keyboard of the black instrument in the choir.

Before long, these toughened soldiers had closed their eyes.

Some had buried their heads in their arms, unable to stop their

shoulders shaking with sobs. On the Polish officers’ handsome

faces, all military stiffness of expression had disappeared to

be replaced by an inexpressible nostalgia for their motherland

that sang from the piano. Next to Cahill one Polish soldier had stood as immobile as a statue throughout the performance, his

arms crossed. When the music ceased, he relaxed. He seemed to

lose the fierce resistance to his emotions, a painfully maintained

self-control, and collapsed within as he groped blindly for a seat

to support him.

Edward stopped playing and, exhausted by his efforts, waited

for a few moments in the silence that descended over the company. He did not dare to separate them from their patriotic dreams.

He understood that he must allow these tough men time to collect themselves before finally launched into a ravishing Carillon

de Noël of his own composition. He concluded the concert with

a dazzling interpretation of another impromptu by Schubert,

lifting the gloom into the realm of renewed hope.

Silence reigned once more, the faces of the soldiers and officers again froze into stoic immobility as the Polish internees

left the church and plunged into the clammy mist and ice that

enshrouded their camp. They carried in their hearts a seemingly

interminable depression.

* * *

The morality of the neutral stance taken by Switzerland during

the Second World War has been discussed at length but it enabled

Eddie and many others to carry out vital humanitarian tasks

which would otherwise have been impossible if the country had

been occupied by the Nazis. In addition to giving the piano recital

described above, he selflessly despatched three cases of supplies to

the camp at Büren which contained a precious radio for the canteen,

over a thousand packets of cigarettes, Swiss chocolates, tens of

pairs of slippers, dozens of razors, razor blades, bars of shaving

soap, toothbrushes and toothpaste, bootlaces, socks, handkerchiefs,

sponges and combs.

* For the following rare first-hand poetic description of a concert by Eddie in wartime I am indebted to the then 29-year-old Colette Muret who wrote a fine, if rather ‘purple’ review in French (which I have translated and paraphrased) for La Revue de Lausanne sometime in December 1940. Muret, ‘la doyenne of Vaud journalists’, died in 2009 at the age of 98.

* * * * * *

On publication, myself and Michael Cathcart from the Books & Arts programme on the ABC in Australia (equivalent to the BBC) presented an attractive and entertaining 18 minute segment on the book with short musical illustrations of his playing of Chopin and Liszt. This programme was made with the technical assistance of Polish National Radio 2 - Dwojka

https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/booksandarts/the-life-of-a-concert-pianist/8285406

If you wish to listen to him play:

https://app.box.com/s/w470tiq0qbbckttbjb4wvj8936zl60vn

|

| Edward Cahill giving a wartime charity recital in the Kursaal Montreux, Switzerland, 1941 |

If you wish to listen to him play:

https://app.box.com/s/w470tiq0qbbckttbjb4wvj8936zl60vn

In Poland Edward Cahill was also the subject of a Duza Czarna programme on Polish National Radio Dwojka. This is a highly respected two hour programme aired each Saturday afternoon devoted to important historical musical artists. If you are Polish you may like to listen although some of it is in English. Many of the miraculously preserved recordings by Cahill were played and discussed by the respected experts in this field Jakub Puchalski and Przemysław Psikuta. The programme also featured the legendary Russian pianist Arthur Friedheim.

* * * * * *

For more detail on the book and recordings: http://scholarly.info/book/the-pocket-paderewski-the-beguiling-life-of-the-australian-concert-pianist-edward-cahill/

Comments

Post a Comment