53rd Nohant Chopin Festival - 'Chopin and the Romantic Exile' - Reviews of recitals from 17th July - 24 July 2019

I had read books, correspondence and seen many films dealing with the highly creative romantic relationship between the great French writer and polemicist George Sand and the composer Fyrderyk Chopin at Nohant-Vic in the Berry region of central France. He wrote many of his immortal pieces there. I felt I must make the effort to attend at least once, despite the rather complex journey from Warsaw.

Sand adored Nature, her beautiful maison and the entire Berry region, in particular the charming and picturesque nearby town of La Châtre. For many music lovers (even obsessives), the works of Chopin have rather eclipsed the extraordinary position George Sand occupied in the France of the day. She was an exceptionally prolific writer, polemicist and political activist - in addition possessed of an extraordinary insight into human romantic psychology with an incisive sense of humour and esprit.

Click on photographs to enlarge - far superior rendition

Sand adored Nature, her beautiful maison and the entire Berry region, in particular the charming and picturesque nearby town of La Châtre. For many music lovers (even obsessives), the works of Chopin have rather eclipsed the extraordinary position George Sand occupied in the France of the day. She was an exceptionally prolific writer, polemicist and political activist - in addition possessed of an extraordinary insight into human romantic psychology with an incisive sense of humour and esprit.

Click on photographs to enlarge - far superior rendition

|

| Le maison de George Sand |

|

| The bust of Chopin outside the entrance to the Bergerie Courtyard |

|

Bergerie-Auditorium du Domaine de George Sand à Nohant where the recitals take place |

|

| One variety of superb landscape surrounding the festival - harvest time now |

Wednesday 17 July 20.30 - Akiko Ebi

The first noticeable and joyful visual matter for me was the presence of a magnificent new C. Bechstein 9' Concert Grand piano on the stage! What a rare sight this is with the ubiquitous Steinway in so many world concert halls. An inspired choice. We miss a great deal of variety of tonal colour and sonic palette now that the instruments of so many once great makers, once common on concert stages, have almost vanished.

I was familiar and highly impressed with this Japanese pianist from her period recording of the Chopin Preludes on the NIFC Black label. She is a great favourite here in Nohant after a legendary concert with Martha Argerich two years ago and on other occasions. She opened with that great integrated sculpture in sound, the Chopin B-flat minor sonata Op. 35 (1837-39). Chopin completed this work at Nohant while living with George Sand. Sonatas were rather surprising at this time and had fallen away in popularity.

I am writing here a Sonata in B flat minor which will contain my March which you already know. There is an Allegro, then a Scherzo in E flat minor, the March and a short Finale about three pages of my manuscript-paper. The left hand and the right hand gossip in unison after the March. ... My father has written to say that my old sonata [in C minor, Op. 4] has been published and that the German critics praise it. Including the ones in your hands I now have six manuscripts. I'll see the publishers damned before they get them for nothing.

The Grave opening had the nobility of a tragic Greek utterance and the Doppio movimento that followed was replete with unexpectedly powerful masculine strength and conviction. The powerful and almost demented rhythms of the Scherzo Ebi brought off with the intense communication of a passionate utterance. A few 'technical' solecisms crept in during this live performance, understandable whenever any pianist takes the risk of playing at their absolute limit. Live performances always involve a metaphysical communication dimension to my mind - absent from studio recordings - a view shared by Arthur Rubinstein. One immediately overlooked them (as one did with Cortot, Arrau, Schnabel and other immortals) as one responded to her fine tone colour, touch, articulation, phrasing and absolute personal commitment to the spirit of this often inaccessible composer.

The Marche funèbre had a chequered compositional history to say the least but like many choices of genius, this music subliminally expresses the grief and anguish of death. The central lyrical section transports us into a mood of melancholic reminiscence of the departed, an experience common to all humanity at funerals. Ebi accomplished this introspection movingly. Much is made of the image of 'wind over the graves' in the final Presto but in light of Chopin's view cited above as 'gossip' have we invested too much melancholy and grief here? Of course after any funeral there is much chatter usually of an uplifting kind, concerning the deceased and reminiscences of their life. Then again composers are often unaware of the associations and connotations their music is calling up in the mind of the listener. A work of genius has manifold interpretations.

This was followed by a subtle and poetic Berceuse Op. 57 (composed in the summer of 1843 at Nohant for Louise, the baby daughter of Pauline Viardot). Her interpretation contained a deeply moving tenderness, refinement and and poetry that was most affecting. It is well known Chopin loved children and they loved him. For me this work speaks of a haunted yearning for his own child, a lullaby performed in his sublimely imaginative mind, isolated and alone. No, not a common feeling about the work and possibly over-interpreted on my part.

The Barcarolle I felt did not quite emerge as she had anticipated but a relatively satisfying performance nevertheless. The Scherzo No 3 in C-sharp minor Op.39 was at once a fine and noble account approaching some grandeur at the conclusion. Dedicated to his pupil Adolf Gutman, this was last work the composer sketched during the Majorca sojourn and in the atmosphere of Valldemossa. Chopin was ill at the time which interrupted and perhaps affected the writing. ‘…questions or cries are hurled into an empty, hollow space – presto con fuoco.’ (Tomaszewski).

The two Nocturnes Op. 62 suited her refinement and delicacy to perfection and were affecting in this place we associate so much with love during summer nights, alive with stars and moths.

Then the four mazurkas Op. 41. George Sand wrote of the first in E minor, composed and first played on Majorca, that it transported us into ‘a land more lovely than the one we behold’. This piece is special. In the E minor Mazurka, we hear a distinct Polish echo: the melody of a song about an uhlan and his girl, ‘Tam na błoniu błyszczy kwiecie’ [Flowers sparkling on the common] (written by Count Wenzel Gallenberg, with words by Franciszek Kowalski) – a song that during the insurrection in Poland had been among the most popular. Chopin quoted it almost literally, at the same time heightening the drama, giving it a nostalgic, and ultimately all but tragic, tone.

The second in the set in B major was most probably composed at Nohant but there are Majorcan folk elements here. Clearly Ebi chose the mazurkas carefully. The simplicity of the folk elements from the Kuyavia region of north-central Poland were made much of in this interpretation. The fourth Mazurka in C-sharp minor was composed during Chopin's first summer at Nohant. The Hungarian composer Stephen Heller described this most beautiful of Chopin mazurkas lyrically: ‘What with others was a refined embellishment, with him was a colourful bloom; what with others was technical fluency, with him resembled the flight of a swallow’. Ebi gave is a beautiful interpretation surely reflecting Chopin's absolute happiness during that first Nohant summer.

The second in the set in B major was most probably composed at Nohant but there are Majorcan folk elements here. Clearly Ebi chose the mazurkas carefully. The simplicity of the folk elements from the Kuyavia region of north-central Poland were made much of in this interpretation. The fourth Mazurka in C-sharp minor was composed during Chopin's first summer at Nohant. The Hungarian composer Stephen Heller described this most beautiful of Chopin mazurkas lyrically: ‘What with others was a refined embellishment, with him was a colourful bloom; what with others was technical fluency, with him resembled the flight of a swallow’. Ebi gave is a beautiful interpretation surely reflecting Chopin's absolute happiness during that first Nohant summer.

She completed her recital with a fine and eloquent performance of the third Ballade Op. 47. The Chopin Ballades are rather like small operas and intensely reflect the fluctuating 'moving toy-shop of the heart'. Again composed at Nohant this radiant Ballade fluctuates in its moods and of course has attracted many suppositions of a programmatic content despite Chopin's intense dislike of this idea applied to his music. Schumann wrote of the ‘breath of poetry’ breathing from this great work. The German violinist and critic Friedrich Niecks heard in the Ballade ‘a quiver of excitement’. ‘Insinuation and persuasion cannot be more irresistible,’ he wrote, ‘grace and affection more seductive’. For the Polish pedagogue and pianist Jan Kleczynski, it is ‘evidently inspired by [Adam Mickiewicz’s tale of] Undine. A supremely romantic inspiration flows like a country stream through beds of summer wild-flowers.' Ebi gave us a truly Romantic performance which for me balanced Chopin's masculine strength and feminine sensibility - surely so characteristic of his music in general.

Jean-Paul Gasparian Thursday 18th July 20.30

This accomplished young pianist has played at Nohant before and is featured on the Aldo Ciccolini 2014 archive recording - a performance of the Schumann Sonata No: 2 Op.22. He has just recorded an all Chopin CD for the Evidence label. Gasparian studied with outstandingly brilliant teachers and is much in demand at many prestigious music festivals in renowned musical venues throughout Europe.

He opened his recital with the Chopin Nocturne in C minor Op.48 No 1 composed at Nohant in the summer of 1841. He adopted a tempo of what one might call mournful, majestic despair that permeates this piece. The great bass notes in the first section fell like statements of paradise lost, the central section a nostalgic and yearning chorale leading into the passionate utterance and agitation of the final section with an almost abnegation of life and final resignation to fate. A fine performance that touched many of these rare domains of emotion.

For the next Nocturne in D flat major Op.27 No: 2 I can do no better than turn to André Gide where in his Notes on Chopin he writes of Chopin with a view that can be illuminatingly applied to this supremely romantic Nocturne. ‘[Chopin] seemed to be constantly seeking, inventing, discovering his thought little by little. This kind of charming hesitation, of surprise and delight, ceases to be possible if the work is presented to us, no longer in a state of successive formation, but as an already perfect, precise and objective whole.’ Gasparian 'sang' the moving cantilena with a yearning solo voice that always remained affectingly beautiful.

Then the Ballade in A-flat major Op.47 No 3 composed at Nohant in the summer of 1841. The Chopin Ballades are rather like small operas and should intensely reflect the fluctuating 'moving toy-shop of the heart'. Again composed at Nohant this radiant Ballade fluctuates in its moods and of course has attracted many suppositions of a programmatic content, despite Chopin's intense dislike of this idea applied to his music. Schumann wrote of the ‘breath of poetry’ flowing from this great work. The German violinist and critic Friedrich Niecks heard in the Ballade ‘a quiver of excitement’. ‘Insinuation and persuasion cannot be more irresistible,’ he wrote, ‘grace and affection more seductive’. For the Polish pedagogue and pianist Jan Kleczynski it is ‘evidently inspired by [Adam Mickiewicz’s tale of] Undine. A supremely romantic inspiration flows like a country stream through beds of summer wild-flowers.' Gasparin too gave us a truly Romantic performance which for me balanced Chopin's masculine strength and feminine sensibility - surely so characteristic of his music in general.

Written at Nohant in the summer of 1842, the beautiful 'innocent' childlike opening to the 'life opera' which is the Ballade in F minor Op.52 gently and tenderly caressed us. This was a fine performance of this masterpiece with well drawn internal cantabile lines and the bel canto eloquent. The musical narrative was musically coherent and unfolded like the wings of a moth at dusk. So much detail and nuance were organically revealed here, growing from within not merely applied to the surface. He wound up the drama like a tight watch spring to the passionate coda and then the relaxation and final triumphant statement chord of faith suffused with resignation which concludes the work. The Polish poet, prose writer, dramatist and translator Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz compared the F minor Ballade’s mysterious, enigmatic character to the inscrutable, elliptical canvases of Caspar David Friedrich and felt that its message transcended the perfection of the music itself, transporting us into another dimension, another realm.

After the interval we heard some quite magnificent Rachmaninoff. One does not expect a French pianist to have a deep, idiomatic understanding of Rachmaninoff, but we were in for a surprise!

He opened his recital with the Chopin Nocturne in C minor Op.48 No 1 composed at Nohant in the summer of 1841. He adopted a tempo of what one might call mournful, majestic despair that permeates this piece. The great bass notes in the first section fell like statements of paradise lost, the central section a nostalgic and yearning chorale leading into the passionate utterance and agitation of the final section with an almost abnegation of life and final resignation to fate. A fine performance that touched many of these rare domains of emotion.

For the next Nocturne in D flat major Op.27 No: 2 I can do no better than turn to André Gide where in his Notes on Chopin he writes of Chopin with a view that can be illuminatingly applied to this supremely romantic Nocturne. ‘[Chopin] seemed to be constantly seeking, inventing, discovering his thought little by little. This kind of charming hesitation, of surprise and delight, ceases to be possible if the work is presented to us, no longer in a state of successive formation, but as an already perfect, precise and objective whole.’ Gasparian 'sang' the moving cantilena with a yearning solo voice that always remained affectingly beautiful.

Then the Ballade in A-flat major Op.47 No 3 composed at Nohant in the summer of 1841. The Chopin Ballades are rather like small operas and should intensely reflect the fluctuating 'moving toy-shop of the heart'. Again composed at Nohant this radiant Ballade fluctuates in its moods and of course has attracted many suppositions of a programmatic content, despite Chopin's intense dislike of this idea applied to his music. Schumann wrote of the ‘breath of poetry’ flowing from this great work. The German violinist and critic Friedrich Niecks heard in the Ballade ‘a quiver of excitement’. ‘Insinuation and persuasion cannot be more irresistible,’ he wrote, ‘grace and affection more seductive’. For the Polish pedagogue and pianist Jan Kleczynski it is ‘evidently inspired by [Adam Mickiewicz’s tale of] Undine. A supremely romantic inspiration flows like a country stream through beds of summer wild-flowers.' Gasparin too gave us a truly Romantic performance which for me balanced Chopin's masculine strength and feminine sensibility - surely so characteristic of his music in general.

He then approached that great masterwork of the Chopin oeuvre, the Polonaise-Fantaisie composed at Nohant in the summer of 1845. His approach indicated an almost complete grasp of the complexities of this late work. Chopin experienced much compositional grief and torment during its gestation and birth. Gasparian's strong left hand on the Bechstein brought out much of the usually concealed counterpoint (of which Chopin was one of the greatest masters since Bach) and polyphony. He conveyed a sense of żal, a Polish word in this context meaning regret leading to a mixture of resentment and anger in the face of unavoidable fate. A deeply moving performance for me of a complex work written when Chopin was moving towards the cold embrace of death.

After the interval we heard some quite magnificent Rachmaninoff. One does not expect a French pianist to have a deep, idiomatic understanding of Rachmaninoff, but we were in for a surprise!

Prelude Op. 23 No.4 in D major. This famous Prélude flowers slowly and possesses a rather Nocturne-like atmosphere. It rises to a climacteric demonstrating Rachmaninoff's melodic gift in all its glorious and grand spaciousness. Gasparian rose to the climax in intense and rhapsodic motion, the revelation of its heart revealed, yet at a passionate and considered tempo.

Prelude Op. 23 No.7 in C minor. This Prélude is a glittering study with elaborate running figuration transporting a slow , fluctuating melody divided between the hands. Gasparian suspended the beautiful and intensely passionate cantabile melodies over a left hand and then the right that flowed like a mountain stream in flood beneath.

The epic third Prelude Op. 32 No.10 in B minor is one of the greatest of Rachmaninoff's in this form. A reflective elegy builds to a punishing contrasting climacteric with the melody hammered out. The ecstasy fades inexorably to resignation in the quiet conclusion. Gasparian express these anxious and rather tortured emotions with great understanding and fine shades of pianistic colour, phrasing, tone and touch.

Completed not long after the Third Piano Concerto when the composer had moved to Rome, the Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor Op. 36 No.2 is a showcase of those qualities that make Rachmaninoff's music so accessible and attractive. However, because his two daughters had contracted typhoid fever, he could not finish the composition in Rome and moved to Berlin to consult physicians. When the girls had improved, Rachmaninoff returned to his Ivanovka country estate, where he finally finished the second piano sonata. Its premiere took place in Kursk on 18 October 1913.

Gasparian made the most of these characteristic Rachmaninoff qualities with idiomatic understanding. His grasp of the polyphonic nature of much of this music was an inspiring surprise. The Allegro agitato immediately took hold of the imagination with its arpeggiated plunge to the bass and rhapsodic 'waves of kinetic nervosité' 'It is the entrance of a great actor' commented the music critic Adrian Corleonis. We heard Rachmaninoff's 1931 revision. The second movement following immediately is a melancholic, nostalgic elegy before another precipitous fall in an arpeggiated descent to the psychologically, somewhat unstable, formidable finale with its surging melodies and compelling triumphal close.

Gasparian took this sonata as if in the talons of an eagle and presented it to us in a magnificently noble, impassioned, coherent yet transparent fashion. The entire complex of moods and shifts, like sun and shadow in a landscape painting, passionately played as if over the Russian steppe. One was simply carried away unresisting on an emotional journey like no other.

|

| The orchard in the garden of George Sand. Delacroix wrote some deeply poetic descriptions of her garden |

Louis SCHWIZGEBEL, piano Friday 19th July 20.30

This pianist was born in 1987 into a family of artists from Switzerland and China. Louis Schwizgebel’s performances are steeped in imagination, rich in colour and musical insight. A refined pianist, Louis is hailed repeatedly for the clarity of his playing and his exceptional fingerwork. At the age of seventeen, he won the Geneva International Music Competition and, two years later, the Young Concert Artists International Auditions in New York. In 2012 he won second prize at the Leeds International Piano Competition and between 2013-2015 he was a BBC New Generation Artist.

This pianist was born in 1987 into a family of artists from Switzerland and China. Louis Schwizgebel’s performances are steeped in imagination, rich in colour and musical insight. A refined pianist, Louis is hailed repeatedly for the clarity of his playing and his exceptional fingerwork. At the age of seventeen, he won the Geneva International Music Competition and, two years later, the Young Concert Artists International Auditions in New York. In 2012 he won second prize at the Leeds International Piano Competition and between 2013-2015 he was a BBC New Generation Artist.

Frédéric CHOPIN 24 Préludes, Op. 28

n° 1 en ut majeur

(Agitato)

n° 2 en la mineur

(Lento)

n° 3 en sol

majeur (Vivace)

n° 4 en mi mineur

(Largo)

n° 5 en ré majeur

(Allegro molto)

n° 6 en si mineur

(Lento assai)

n° 7 en la majeur

(Andantino)

n° 8 en fa dièse

mineur (Molto agitato)

n° 9 en mi majeur

(Largo)

n° 10 en do dièse

mineur (Allegro molto)

n° 11 en si

majeur (Vivace)

n° 12 en sol

dièse mineur (Presto)

n° 13 en fa dièse

majeur (Lento)

n° 14 en mi bémol

mineur (Allegro)

n° 15 en ré bémol

majeur (Sostenuto)

n° 16 en si bémol

mineur (Presto con fuoco)

n° 17 en la bémol

majeur (Allegretto)

n° 18 en fa

mineur (Allegro molto)

n° 19 en mi bémol

majeur (Vivace)

n° 20 en ut

mineur (Largo)

n° 21 en si bémol

majeur (Cantabile)

n° 22 en sol

mineur (Molto agitato)

n° 23 en fa

majeur (Moderato)

n° 24 en ré

mineur (Allegro appasionnato)

I cannot go into the detail of his rather disappointingly straightforward approach to each Prelude, save to say he gave a finely balanced, fluently virtuosic and emotional account of the cycle. His tone and touch are perfectly honed for Chopin.

It would of course have been impossible for Chopin to have ever considered performing this complete radical cycle in his musical and cultural environment (not least because of the brevity of many of the pieces). It is unlikely ever to have even occurred to him the way programmes were designed piecemeal at the time. I tend to feel the performance of them as a cycle is of course possible but not justified. In some of his programmes and others of the period, a few preludes are scattered randomly through them like diamond dust. Each piece contains within it entire worlds and destinies of the human spirit.

It is now well established by structuralists as a complete work, a masterpiece of integrated yet unrelated ‘fragments’ (in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century sense of that aesthetic term). Each prelude can of course stand on its own as a perfect miniature landscape of emotional feeling and tonal climate. Chopin said himself that emotion was the overriding, most important factor in musical appreciation. Specific emotions were associated with specific keys at the time. But ‘Why Preludes? Preludes to what?’ André Gide asked. One explanation is that the idea of 'preluding' as an improvisational activity in the same key for a short time before a large keyboard work was to be performed was well established in Chopin's day but has been abandoned in modern times.

I think it unnecessary and superfluous to actually answer this question. We must to turn to Chopin’s love of Bach to at least partially understand them and hist structural ideal (he took an edition of the ‘48’ to Mallorca where he completed the Preludes). I think it was Anton Rubinstein who first performed them as a cycle but I stand to be corrected on this. Some performers of the cycle (Sokolov, Argerich, the greatest historically to my mind by Alfred Cortot) give one the impression of an integrated 'philosophy' or spiritual narrative which I felt was lacking here despite the virtuosity and clarity of voicing and polyphony.

It would of course have been impossible for Chopin to have ever considered performing this complete radical cycle in his musical and cultural environment (not least because of the brevity of many of the pieces). It is unlikely ever to have even occurred to him the way programmes were designed piecemeal at the time. I tend to feel the performance of them as a cycle is of course possible but not justified. In some of his programmes and others of the period, a few preludes are scattered randomly through them like diamond dust. Each piece contains within it entire worlds and destinies of the human spirit.

It is now well established by structuralists as a complete work, a masterpiece of integrated yet unrelated ‘fragments’ (in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century sense of that aesthetic term). Each prelude can of course stand on its own as a perfect miniature landscape of emotional feeling and tonal climate. Chopin said himself that emotion was the overriding, most important factor in musical appreciation. Specific emotions were associated with specific keys at the time. But ‘Why Preludes? Preludes to what?’ André Gide asked. One explanation is that the idea of 'preluding' as an improvisational activity in the same key for a short time before a large keyboard work was to be performed was well established in Chopin's day but has been abandoned in modern times.

I think it unnecessary and superfluous to actually answer this question. We must to turn to Chopin’s love of Bach to at least partially understand them and hist structural ideal (he took an edition of the ‘48’ to Mallorca where he completed the Preludes). I think it was Anton Rubinstein who first performed them as a cycle but I stand to be corrected on this. Some performers of the cycle (Sokolov, Argerich, the greatest historically to my mind by Alfred Cortot) give one the impression of an integrated 'philosophy' or spiritual narrative which I felt was lacking here despite the virtuosity and clarity of voicing and polyphony.

I like to consider the Preludes as 'Fragments' analogously placed in the architecture of say the English landscape garden, pregnant with unfinished meaning, repositories of implied emotional significance. The notion was formed in the eighteenth century concerning the poetic significance of eloquent 'ruins' (a ruined castle tower, a nymph among the trees, a pond, an amphitheater) placed strategically in landscape gardens as embracing the 'picturesque' philosophy. An example would be the seminal garden of Rousham in Oxfordshire designed by William Kent. This was the beginning or birth of intellectual emotions. Here it is musical forms that are unfinished and catalyze emotional evocations.

The preludes surely extend the prescient Chopin remark 'I indicate, it's up to the listener to complete the picture'. Or in the words of Walter Benjamin, the fragment (the Prelude in this case) is full of potential, leaving unfinished the full statement - except in a few cases. The so-called 'Raindrop' Prelude is a self-consistent, complete work but even then this conception may be argued. For Benjamin, allegory (fragment or an individual prelude) was the “authentic way of dealing with the world, because it is not based on a premise of unity but accepts the world as fragmented, as failed.”

The preludes surely extend the prescient Chopin remark 'I indicate, it's up to the listener to complete the picture'. Or in the words of Walter Benjamin, the fragment (the Prelude in this case) is full of potential, leaving unfinished the full statement - except in a few cases. The so-called 'Raindrop' Prelude is a self-consistent, complete work but even then this conception may be argued. For Benjamin, allegory (fragment or an individual prelude) was the “authentic way of dealing with the world, because it is not based on a premise of unity but accepts the world as fragmented, as failed.”

Interval

Modeste MOUSSORGSKY Tableaux d’une exposition

(Pictures at an Exhibition)

Promenade

Gnome

Promenade

Le vieux

château

Promenade

Les

Tuileries

Bydlo

Promenade

Ballet

des poussins dans leur coque

Samuel

Goldenberg et Schmuyle

Promenade

Le marché de

Limoges

Catacombe

Cum mortuis

in lingua mortua

La cabane

sur des pattes de poule

La grande

porte de Kiev

|

| Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881) at age 26 |

To conclude this excellent recital, Schwizgebel chose Pictures at an Exhibition (1874) by Mussorgsky. It was a proud performance full of nobility and colour. The rhythm he achieved in the Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks was at once amusing and brilliant, the Hut on Fowl's Legs quite terrifying. Catacombe poetic and haunting.

This was a powerful and idiomatic interpretation of the work with many moments of fine pianistic colour and detail. The tempo adopted for the Promenade should bear in mind that this is a portrait of a man walking around an art exhibition (the pictures painted by Mussorgsky's friend, the artist and architect Viktor Hartmann). The composer is reminiscing on this past friendship now suddenly and tragically cut short when the young artist died suddenly of an aneurysm. The visitor walks at a fairly regular pace but perhaps not always as his mood fluctuates between grief and elated remembrance of happy times spent together. This is always a challenge for the pianist but for me this Promenade was at the proper tempo although it seems I personally wander more slowly and less heavily around art galleries.

The art exhibition was of Hatmann's drawings and watercolours (not strong oil paintings) and I feel this should be considered when approaching the dynamic range of any performance in order to avoid undue heaviness.

The art exhibition was of Hatmann's drawings and watercolours (not strong oil paintings) and I feel this should be considered when approaching the dynamic range of any performance in order to avoid undue heaviness.

|

| Viktor Hartmann's costumes for the ballet Trilby which Moussorgsky attended and inspired the 5th movement |

The bass of this new Bechstein at Nohant is less resonant than a Steinway which prevents such a work from tempting the virtuoso pianist to overwhelm the audience with sound. Particularly in this work the final movement Богатырские ворота (В стольном городе во Киеве) The Bogatyr Gates which depicts the Great Gate of Kiev begs for a controlled monumental sound. I shall never forget the shattering performance at Duszniki Zdroj in Poland some years ago by the inspired Russian pianist Denis Kozhukhin when we could distinctly hear the Orthodox bells tolling and see the Great Gate of Kiev before the mind's eye.

| ||||||||||||

| Viktor Hartmann - Plan for a City Gate at Kiev

I am finding it quite difficult to write my reviews of this festival in my normal way as there are so many extraordinary events, special invitations, receptions, interviews, masterclasses and recitals throughout the day and evening.

I attended Masterclasses each day at 10.00am, conducted by that fine teacher and director of the festival, the French pianist and pedagogue, Yves Henry. There are three 'students' - one Pole (Mateusz Krzyzowski) and two Japanese of various levels of proficiency and experience (Sayoko Kobayashi and Hiroshi Tsuganezawa).

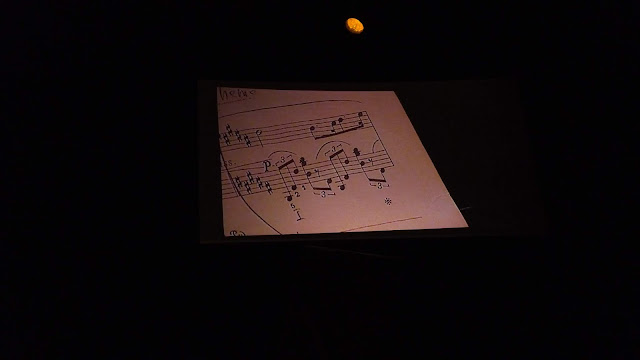

In the elucidation of points in the score an excellent idea was to project the bars under discussion onto a screen above the audience. He usually used the annotated personal score of the student. Also at various moments the facsimile score was referred to if available. A facsimile of the Chopin Preludes in readily available and gives a profound insight into Chopin's psychological and musical thought, often quite different to an editor's interpretation of the score. This together with musical illustrations on the Pleyel instrument was an invaluable resource to assist the student in a contextual, historical understanding of these often musically inaccessible works.

Yves Henry examining Chopin Mazurkas with Hiroshi Tsuganezawa. Notice the period Pleyel grand piano in the immediate foreground on the right

This Masterclass was followed by an al fresco lunch in a picturesque estate in the country owned by the Vice-President of the festival, Sylviane Plantelin - all rather Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie in character.

Saturday 20th July 18.00

At 6.00 pm in the superb courtyard of George Sand's maison, actors read from the correspondence between George Sand and Gustave Flaubert, each reading punctuated by Chopin mazurkas played on a period Pleyel of 1839. This took place in the enchanting garden. Georges Sand was a talented and wonderfully imaginative gardener with an extensive knowledge of plants. The windows of the maison had been thrown open and the music floated out from the interior in the most romantic manner conceivable, played by Yves Henry. Yes, as if the composer was playing himself - something I remember used to happen at his birthplace outside Warsaw at Żelazowa Wola.

The Dining Room

The place setting for Fryderyk Chopin

Chopin's Room (inhabited from 1839-1846) Actually only half of it with the original entrance doors. After his departure Sand divided it into two, the other half becoming a domestic library

George Sand's Bedroom from 1867 until her death in 1876

The Bedroom of Aurore de Saxe. George slept here at the beginning of her marriage. It accommodated many guests who visited Sand such as Liszt and Marie d'Agoult, Pauline Viardot and Delacroix. It was the bedroom of the young Solange, then of Maurice and Lina. The room has retained its wood panelling, Louis XVI furniture and 'Polish-style' bed

Aurores' Bedroom. George slept in this room from 1808-1822.

Here she listened to Liszt downstairs and wrote of his piano making

'those sounds that the whole universe would like to hear.'

Her granddaughter Gabrielle (who occupied the room from 1892-1909) introduced the bamboo furniture and Art Nouveau wallpaper with herons

In 1850 Sand built a fully equipped private theater for the performance of the plays she wrote

In 1854 the castelet des marionettes or puppet theater was added with hundreds of glove puppets and a battery of enormously varied sound effects

Maurice's Studio. In 1852 Sand installed a studio in the attic in which her highly artistic son could paint and sculpt. This enormous room with its view over the countryside became home to all the varied interests of the Sand household - botany, painting, geology, wood sculpture, anatomical models, collections of insects, seashells and coins as well as theatrical costumes and puppets

An extraordinary violinist puppet sculpted and painted by Maurice

Some costumes and stage paraphernalia used for theatricals

View over Nohant-Vic from Maurice's painting studio

This is the technologically state-of-the-art bathroom and self contained water heater of the house. Sand was always at the cutting edge of new industrial methods which included a flushing lavatory (when commodes and chamber pots were ubiquitous). She also at vast expense constructed a concealed and ducted central heating system throughout the house

The Sand family cemetery at Nohant-Vic

George Sand's grave above |

Tuesday 23 July 15.00

Final concert of the young pianists who attended the Masterclasses

Mateusz KRZYZOWSKI (Poland)

Presented by the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Warsaw

Chopin 24 Preludes Op.28

Hiroshi TSUGANEZAWA (Japan)

Laureat of the Nohant Festival Chopin Competition in Japan 2018

Sayoko KOBAYASHI (Japan)

Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris Alfred Cortot

Final concert of the young pianists who attended the Masterclasses

Mateusz KRZYZOWSKI (Poland)

Presented by the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Warsaw

Chopin 24 Preludes Op.28

I always felt this was an ambitious choice for a young pianist for all the reasons I have outlined above in my commentary on the Prelude cycle. The degree of preparation for these demanding works is formidable, even for the most accomplished of pianists. It was an excellent performance and indicated strongly just how much he has learned and more importantly applied from the inspiration of Yves Henry in the masterclasses. This applied most strongly I felt in terms of selection of the correct character and tempo for each self- contained universe within these so-called 'miniatures'. Time, thought and experience will mature this promising young pianist, giving increased authority to his playing, his own voice and develop his communicative ability.

Hiroshi TSUGANEZAWA (Japan)

Laureat of the Nohant Festival Chopin Competition in Japan 2018

I loved the open communicative temperament of this young man which carried all before it. His radiant smile spoke volumes and expressed his absolute joy at having been given the opportunity not only to come to Nohant masterclasses in faraway France but also to play Chopin!

I noticed he was a particularly fast learner in the Masterclasses. He accepted corrections with a self-effacing smile (Yves Henry is a gentle teacher but firm and insists on correctness) and simply got on with being correct. An excellent attitude in a young pupil temperamentally open to learn everything about Chopin.

The three mazurkas Op.33 were finely played but I felt lacked idiomatic phrasing and relied too much on the pedal to achieve a legato that is not always required in these demanding pieces.

To perform the Sonata No 3 in B minor Op. 58 was ambitious indeed. This is one of the great masterworks of Western keyboard composition and as the great German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler once commented 'A great work of art is a king standing before us. One must permit the time to be addressed by him.’ I would like to leave this advice for Hiroshi

to ponder and allow his teachers to attend to more technical and interpretative matters rather than be tempted into invidious criticism. He has the work in his memory, fingers and mind - an enormous achievement in itself. Now he must develop his own voice.

Sayoko KOBAYASHI (Japan)

Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris Alfred Cortot

From the Masterclasses it was clear from the first notes that here was an accomplished young pianist with her own voice and unarguable authority at the keyboard. She adopted corrections and suggestions from Yves Henry instantly, but only after reflection. Her two Nocturnes Op. 48 were refined, elegant and moving with fine control of touch and tone. She also had the temerity to approach the Chopin Polonaise-Fantasie. Her performance was cohesive, replete with the fluctuating, wildly contrasting emotions that are contained within this demanding piece. A tremendously impressive grasp of the work which I felt had creatively transcended, dare I say, the often encountered 'Japanese performance school' in Chopin. She left room for spontaneity and passion.....a most enjoyable recital.

|

| Lt. to Rt. Hiroshi Tsuganezawa, Sayoko Kobayashi, Yves Henry, Mateusz Krzyzowski |

Yves Henry at the conclusion of the festival, gave us another treat with the Berrichon band on stage. The audience then retired to the Bergerie courtyard garden for a festive glass of Vouvray and protracted fond farewells.

Nohant was certainly the most enjoyable music festival I have ever attended. It combined charm, grace, intellectual content, true love of music and literature as well as being located in the idyllic, intimate atmosphere where one of the greatest creative love affairs in modern history evolved.

Au revoir jusqu'à la prochaine fois!

Comments

Post a Comment