Chopin in the Time of Cholera - the Paris pandemics of 1832 and 1849

|

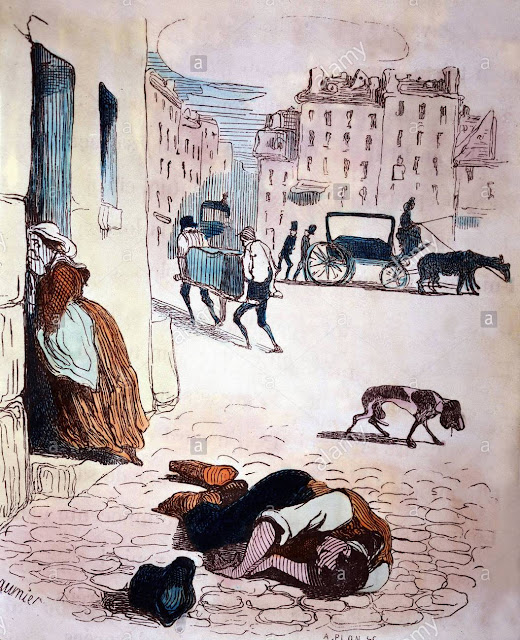

| Honoré Daumier

(1808-1879) 'Cholera' |

Upon his arrival in Paris on 5 October 1831, Chopin had no set plans to stay in the city. However after six weeks residence at an inn near the diligence terminus in the Rue de la Cité Bergère, he took an apartment with a balcony and panoramic views across Paris at 27 Boulevard Poissonnière.

In November 1831 he wrote of his initial impressions in an extraordinarily frank and one might venture 'manly' letter to one of his travelling companions, Alfons Kumelski. He describes the immense contrasts within the city :

'You find here the greatest splendour, the greatest squalor, the greatest virtue, and the greatest vice; at every step you see posters advertising cures for venereal disease - nothing but cries, noise, din, and mud, past anything you can imagine.' Later in the missive he speaks of the large numbers of prostitutes ('sisters of mercy') and confesses to a 'souvenir of Teresa (despite the ministrations of Bénédict who considers my misfortune insignificant) has not allowed me to taste the forbidden fruit. I have already got to know a few lady vocalists - and the ladies here are even more eager for 'duets' than those from the Tyrol. [quoted in Fryderyk Chopin, Alan Walker, London 2018 p.213]

The first few weeks were a financial trial for Chopin. His first public appearance was on 26 February at the Salle Pleyel arranged by the controversial pianist and pedagogue Kalkbrenner. He played the Concerto in E minor in the first half and the spectacular 'Là ci darem' Variations in the second. The concert concluded with a monumental piece in honor of Chopin by Kalkbrenner for six pianos with renowned pianists living in Paris entitled 'Grand Polonaise preceded by an Introduction and March'.

Of Chopin's compositions the distinguished critic François-Joseph Fétis wrote '...an abundance of original ideas of a kind to be found nowhere else.' The twenty-two-year-old Franz Liszt wrote in his biography of Chopin that this concert revealed '...the talent that was opening a new phase of poetic sentiment...' Unfortunately the concert was not well attended and lost money.

Imagine a world without electricity then read on...

Of Chopin's compositions the distinguished critic François-Joseph Fétis wrote '...an abundance of original ideas of a kind to be found nowhere else.' The twenty-two-year-old Franz Liszt wrote in his biography of Chopin that this concert revealed '...the talent that was opening a new phase of poetic sentiment...' Unfortunately the concert was not well attended and lost money.

Imagine a world without electricity then read on...

In 1829 a cholera pandemic had occurred in Russia. It proceeded by slow degrees towards Poland before viciously striking London, whence it became known by the nickname 'King Cholera'. Behaviour was not unlike the cornaravirus today. Then as now, doctors did not know the cause or origin of the disease which caused great fear. Many thought it came from the miasma (polluted air of cities) until it was finally discovered to be carried in polluted water supplies.

On 26 March 1832, six months after Chopin's arrival in the great Parisian metropolis, it claimed its first victim. In a letter to Józef Nowakowski 15 April 1832 Chopin wrote mainly of the effect of the epidemic on his income through the evaporation of lessons from his wealthy aristocratic patrons who had fled to the countryside and the difficulties of giving concerts. Most of the afflicted were dead within a day or two. This six-month cholera epidemic was to claim 7,000 lives in the next two weeks. In total some 19,000 citizens fell victim to the disease. Further from the letter:

'Rossini is leaving. Rubini and Lablache the same, Malibran is in Brussels, Devrient in London; [...] As far as pianists are concerned , Herz is going to England. Mendelssohmn ditto. Pixis to Germany, Lisztto Switzerland, Kalkbrenner doesn't know wat to do, so fearful is he of cholera; Hiller is in Frankfurt'

The German poet Heinrich Heine was living in Paris at the time of the cholera pandemic working as a journalist and examining the development of democracy and capitalism in France. His journals describe the beginning of the Paris Cholera epidemic of 1832. In particular he gave us a colourful account of a ball.

'Rossini is leaving. Rubini and Lablache the same, Malibran is in Brussels, Devrient in London; [...] As far as pianists are concerned , Herz is going to England. Mendelssohmn ditto. Pixis to Germany, Lisztto Switzerland, Kalkbrenner doesn't know wat to do, so fearful is he of cholera; Hiller is in Frankfurt'

He also wrote of the volatile political situation in Paris 'which has paralysed the entire country...' The restoration of the Bourbon dynasty was not welcomed by those of a Republican disposition. Louis-Philippe was sworn in as King Louis-Philippe I on 9 August 1830. At first, he was much loved and called the 'Citizen King' and the 'bourgeois monarch', but his popularity suffered as his government was perceived as increasingly conservative and monarchical. Under his management, the conditions of the working classes deteriorated.

On May 16, 1832, occurred the death of the king's powerful supporter, President of the Council, Casimir Pierre Périer. Then on 1 June 1832, Jean Maximilien Lamarque, a popular former Army commander who became a member of the French parliament and was critical of the monarchy, died of cholera. The riots that followed his funeral sparked the June Rebellion which was ruthlessly crushed and defeated. Victor Hugo described the rebellion in his novel Les

Misérables which is a feature of the musical and film based on the book.

|

| June Rebellion, Paris 1832 |

Chopin witnessed and lived through all these upheavals. Near death in 1849, he faced another cholera pandemic and more serious political upheavals. Four months before his death in a letter to Wojciech Grzymala dated 18 June 1849, he writes with his characteristic humour even then

'...I'm gasping and coughing just the same, it's just that I bear it more easily. I haven't yet begun to play - I am unable to compose - I don't know what sort of hay I'll be eating soon. Everyone is leaving - some from fear of cholera, others from fear of revolution.'

When one examines the historical and social context through which great composers lived, one tends to see them as similar in so many ways as 'ordinary' men rather than inaccessible godlike genius. Context is vital to understanding. They too are beset by financial worries, health horrors, political upheavals and war - all so similar in character to today. He cannot have remained indifferent to the mayhem around him, yet like all men and in particular as a Polish emigre, he was preoccupied with his own destiny and that of his blighted nation. I find it astonishing he was able to compose anything at all!

'...I'm gasping and coughing just the same, it's just that I bear it more easily. I haven't yet begun to play - I am unable to compose - I don't know what sort of hay I'll be eating soon. Everyone is leaving - some from fear of cholera, others from fear of revolution.'

| |

|

The German poet Heinrich Heine was living in Paris at the time of the cholera pandemic working as a journalist and examining the development of democracy and capitalism in France. His journals describe the beginning of the Paris Cholera epidemic of 1832. In particular he gave us a colourful account of a ball.

|

| Alfred Rethel, Death as Cutthroat (1851) |

'That night, the balls were more crowded than ever; hilarious laughter all but drowned the louder music; one grew hot in the chahut, a fairly unequivocal dance, and gulped all kinds of ices and other cold drinks--when suddenly the merriest of the harlequins felt a chill in his legs, took off his mask, and to the amazement of all revealed a violet-blue face. It was soon discovered that this was no joke; the laughter died, and several wagon loads were driven directly from the ball to the Hotel-Dieu, the main hospital, where they arrived in their gaudy fancy dress and promptly died, too...[T]hose dead were said to have been buried so fast that not even their checkered fool's clothes were taken off them; and merrily as they lived they now lie in their graves.' Heinrich Heine

A far more extensive account was written by the American author, poet and editor Nathaniel Parker Willis (1806–1867) He was acquainted with Edgar Allan Poe and the poet Longfellow. He was a highly successful magazine writer. I make no apology for quoting this in full so one may conceive of what Chopin experienced and which must have influenced his febrile musical sensitivities and temperament in some way. Certainly in these early days in Paris, his struggle must have given rise to nostalgia for Poland, as he wrote many Mazurkas and Nocturnes as well as the wild and explosive, yet at times indescribably tender and lyrical, Scherzo in B minor Op.20.

Nathaniel Parker Willis writes:

Nathaniel Parker Willis writes:

March 1832. You will see by the papers, I presume, the official accounts of the cholera in Paris. It seems very terrible to you, no doubt, at your distance from the scene, and truly it is terrible enough, if one could realise it any where—but no one here thinks of troubling himself about it; and you might be here a month, and if you observed the people only, and frequented only the places of amusement and the public promenades, you might never suspect its existence. The month is June-like—deliciously warm and bright, and the trees are just in the tender green of the new buds; and the exquisite gardens of the Tuileries are thronged all day with thousands of the gay and idle, sitting under the trees in groups, and laughing and amusing themselves as if there was no plague in the air, though hundreds die every day; and the churches are all hung in black, with the constant succession of funerals, and you cross the biers and hand-barrows of the sick hurrying to the hospitals at every turn, in every quarter of the city. It is very hard to realise such things, and, it would seem, very hard even to treat it seriously.

I was at a masque ball at the “Theatre des Varieties” a night or two since, at the celebration of the Mi-careme. There were some two thousand people, I should think, in fancy dresses; most of them grotesque and satirical; and the ball was kept up till seven in the morning with all the extravagant gaiety and noise and fun with which the French people manage such matters. There was a cholera-waltz and a cholera-gallopade; and one man, immensely tall, dressed as a personification of the cholera, with skeleton armour and blood-shot eyes, and other horrible appurtenances of a walking pestilence. It was the burden of all the jokes, and all the cries of the hawkers, and all the conversation. And yet, probably, nineteen out of twenty of those present lived in the quarters most ravaged by the disease, and most of them had seen it face to face, and knew perfectly its deadly character.

As yet, the higher classes of society have escaped. It seems to depend very much on the manner in which people live; and the poor have been struck in every quarter, often at the very next door to luxury. A friend told me this morning that the porter of a large and fashionable hotel in which he lives had been taken to the hospital; and there have been one or two cases in the airy quarter of St. Germain. Several medical students have died, too, but the majority of these live with the narrowest economy, and in the parts of the city the most liable to impure effluvia. The balls go on still in the gay world, and I assume they would go on if there were only musicians enough left to make an orchestra, or fashionists to compose a quadrille.

As if one plague was not enough, the city is all alive in the distant faubourgs with revolts. Last night the rappel was beat all over the city, and the National Guard called to arms and marched to the Porte St. Denis and the different quarters where the mobs were collected. The occasion of the disturbance is singular enough. It has been discovered, as you will see by the papers, that a great number of people have been poisoned at the wine-shops. Men have been detected, with what object Heaven only knows, in putting arsenic and other poisons into the cups and even into the buckets of the water-carriers at the fountains. Several of these empoisonneurs have been taken from the officers of justice and literally torn limb from limb, in the streets. Two were drowned yesterday by the mob in the Seine, at the Pont-Neuf. It is believed by many of the common people that this is done by the government, and the opinion prevails sufficiently to produce very serious disturbances. They suppose there is no cholera, except such as is produced by poison; and the Hotel Dieu and the other hospitals are besieged daily by the infuriated mob, who swear vengeance against the government for all the mortality they witness.

I have just returned from a visit to the Hotel Dieu—the hospital for the cholera. I had previously made several attempts to gain admission, in vain, but yesterday I fell in, fortunately, with an English physician, who told me I could pass with a doctor’s diploma, which he offered to borrow for me of some medical friend. He called by appointment at seven this morning, to fulfil his promise. It was like one of our loveliest mornings in June—an inspiriting, sunny, balmy day, all softness and beauty, and we crossed the Tuileries by one of its superb avenues, and kept down the bank of the river to the island. With the errand on which we were bound in our minds, it was impossible not to be struck very forcibly with our own exquisite enjoyment of life. I am sure I never felt my veins fuller of the pleasure of health and motion, and I never saw a day when everything about me seemed better worth living for. The superb palace of the Louvre, with its long facade of nearly half a mile, lay in the mellowest sunshine on our left,—the lively river, covered with boats, and spanned with its magnificent and crowded bridges on our right,—the view of the island with its massive old structures below, — and the fine old gray towers of the church of Notre Dame, rising dark and gloomy in the distance—it was difficult to realise anything but life and pleasure. That under those very towers which added so much to the beauty of the scene, there lay a thousand and more of poor wretches dying of a plague, was a thought my mind would not retain a moment.

A half hour’s walk brought us to the Place Notre Dame, on one side of which, next this celebrated church, stands the Hospital. My friend entered, leaving me to wait till he had found an acquaintance, of whom he could borrow a diploma. A hearse was standing at the door of the church, and I went in for a moment. A few mourners, with the appearance of extreme poverty, were kneeling round a coffin at one of the side-altars, and a solitary priest, with an attendant boy, was mumbling the prayers for the dead. As I came out, another hearse drove up, with a rough coffin scantily covered with a pall, and followed by one poor old man. They hurried in; and, as my friend had not yet appeared, I strolled round the square. Fifteen or twenty water-carriers were filling their buckets at the fountain opposite, singing and laughing, and at the same moment four different litters crossed towards the Hospital, each with its two or three followers, women and children or relatives of the sick, accompanying them to the door, where they parted from them, most probably, forever. The litters were set down a moment before ascending the steps, the crowd pressed around and lifted the coarse curtains, farewells were exchanged, and the sick alone passed in. I did not see any great demonstration of feeling in the particular cases that were before me, but I can conceive, in the almost deadly certainty of this disease, that these hasty partings at the door of the Hospital might often be scenes of unsurpassed suffering and distress. I waited, perhaps, ten minutes more for my friend. In the whole time that I had been there, ten litters, bearing the sick, had entered the Hotel Dieu.

As I exhibited the borrowed diploma, the eleventh arrived, and with it a young man, whose violent and uncontrolled grief worked so far on the soldier at the door, that he allowed him to pass. I followed the bearers up to the ward, interested exceedingly to see the patient, and desirous to observe the first treatment and manner of reception. They wound slowly up the staircase to the upper story, and entered the female department—a long, low room, containing nearly a hundred beds, placed in alleys scarce two feet from each other: nearly all were occupied; and those which were empty, my friend told me, were vacated by deaths yesterday.

They set down the litter by the side of a narrow cot with coarse but clean sheets, and a Soeur de Charite, with a white cap and a cross at her girdle, came and took off the canopy. A young woman of apparently twenty-five was beneath, absolutely convulsed with agony. Her eyes were started from the sockets, her mouth foamed, and her face was of a frightful, livid purple. I never saw so horrible a sight. She had been taken in perfect health only three hours before, but her features looked to me marked with a year of pain. The first attempt to lift her produced violent vomiting, and I thought she must die instantly. They covered her up in bed, and, leaving the man who came with her hanging over her with the moan of one deprived of his senses, they went to receive others who were entering in the same manner. I inquired of my friend, how soon she would be attended to. He said, “Possibly in an hour, as the physician was just commencing his rounds.” An hour after, I passed the bed of this poor woman, and she had not yet been visited. Her husband answered my question with a choking voice and a flood of tears.

I passed down the ward, and found nineteen or twenty in the last agonies of death. They lay quite still, and seemed benumbed. I felt the limbs of several, and found them quite cold. The stomach only had a little warmth. Now and then a half groan escaped those who seemed the strongest, but with the exception of the universally open mouth and upturned ghastly eye, there were no signs of much suffering. I found two, who must have been dead half an hour, undiscovered by the attendants. One of them was an old woman, quite grey, with a very bad expression of face, who was perfectly cold—lips, limbs, body and all. The other was younger, and seemed to have died in pain. Her eyes looked as if they had been forced half out of the sockets, and her skin was of the most livid and deathly purple. The woman in the next bed told me she had died since the Soeur de Charite had been there. It is horrible to think how these poor creatures may suffer in the very midst of the provisions that are made professedly for their relief. I asked why a simple prescription of treatment might not be drawn up by the physician, and administered by the numerous medical students who were in Paris, that as few as possible might suffer from delay. “Because,” said my companion, “the chief physicians must do everything personally to study the complaint.” And so, I verily believe, more human lives are sacrificed in waiting for experiments than ever will be saved by the results.

My blood boiled from the beginning to the end of this melancholy visit. I wandered about alone among the beds till my heart was sick, and I could bear it no longer, and then rejoined my friend, who was in the train of one of the physicians making the rounds. One would think a dying person should be treated with kindness. I never saw a rougher or more heartless manner than that of the celebrated Dr. __ at the bed-sides of these poor creatures. A harsh question, a rude pulling open of the mouth to look at the tongue, a sentence or two of unsuppressed comment to the students on the progress of the disease, and the train passed on. If discouragement and despair are not medicines, I should think the visits of such physicians were of little avail. The wretched sufferers turned away their heads after he had gone, in every instance that I saw, with an expression of visibly increased distress. Several of them refused to answer his questions altogether.

On reaching the bottom of the Salle St. Monique, one of the male wards, I heard loud voices and laughter. I had heard much more groaning and complaining in passing among the men, and the horrible discordance struck me as something infernal. It proceeded from one of the sides to which the patients had been removed who were recovering. The most successful treatment had been found to be punch —very strong, with but little acid; and, being permitted to drink as much as they would, they had become partially intoxicated. It was a fiendish sight, positively. They were sitting up, and reaching from one bed to the other, and with their still pallid faces and blue lips, and the hospital dress of white, they looked like so many carousing corpses. I turned away from them in horror.

I was stopped in the door-way by a litter entering with a sick woman. They set her down in the main passage between the beds, and left her a moment to find a place for her. She seemed to have an interval of pain, and rose up one hand and looked about her very earnestly. I followed the direction of her eyes, and could easily imagine her sensations. Twenty or thirty death-like faces were turned towards her from the different beds, and the groans of the dying and the distressed came from every side, and she was without a friend whom she knew: sick of a mortal disease, and abandoned to the mercy of those whose kindness is mercenary and habitual, and, of course, without sympathy or feeling. Was it not enough alone, if she had been far less ill, to embitter the very fountains of life, and make her almost wish to die? She sank down upon the litter again, and drew her shawl over her head.

I had seen enough of suffering; and I left the place. On reaching the lower staircase, my friend proposed to me to look into the dead-room. We descended to a large dark apartment below the street level, lighted by a lamp fixed to the wall. Sixty or seventy bodies lay on the floor, some of them quite uncovered, and some wrapped in mats. I could not see distinctly enough by the dim light to judge of their discolouration. They appeared mostly old and emaciated. I cannot describe the sensation of relief with which I breathed the free air once more. I had no fear of the cholera, but the suffering and misery I had seen oppressed and half smothered me. Everyone who has walked through a hospital will remember how natural it is to subdue the breath, and close the nostrils to the smells of medicine and the close air. The fact too, that the question of contagion is still disputed, though I fully believe the cholera not to be contagious, might have had some effect. My breast heaved, however, as if a weight had risen from my lungs, and I walked home to my breakfast, blessing God for health with undissembled gratitude.

[Pencillings by the Way, Nathaniel Parker Willis 1836, quoted courtesy of Chris Woodyard of Haunted Ohio]

Comments

Post a Comment