16th.Chopin and His Europe Festival (Chopin i jego Europa) 15-31 August 2020, Warsaw, Poland

Programme and Programme Notes

https://festiwal.nifc.pl/en/2020/kalendarium

We regret to announce that due to the progress of the pandemic in North America, pianists Garrick Ohlsson and Charles Richard-Hamelin have been obliged to withdraw from the 16th Chopin and His Europe Festival.

As the festival programme

(link above) now has full and informative online background historical notes on

the genesis of works to be performed by eminent musicologists, this aspect of

my reviewing is no longer necessary.

I shall restrict myself mainly

to personal assessment of performances

Profile of the Reviewer Michael Moran

https://en.gravatar.com/mjcmoran#pic-0

The pandemic and seat distancing in the audience, all wearing masks of various hues and patterns, has created a rather melancholic although occasionally lighthearted vista of deprivation in the Filharmonia. Scarcely any excited joyful conversation and 'buzz' at the festival opening and the absence of many friends.

Psychologically life has become unaccountably self-conscious as one is

unavoidably besieged by the suspicion that a nearby stranger may be infected

asymptomatically. Sole eye contact remains a strange phenomenon but curiously

expressive and seems to carry subliminal messages difficult to decode

accurately. In Western culture, reading communicative eyes behind a mask is an

unfamiliar experience, whereas in other cultures it is a custom. The lack of an

interval means musical conversation and the expression of feelings concerning

'the programme so far' has disappeared. At the conclusion most simply left the

hall with minimal social interaction.

The fact the

festival is being mounted at all is a triumph of courage and tenacity on the

part of the Chopin Institute, the loyal and indefatigable Director, Artistic

Director, PR Manager and staff. They are all to be congratulated.

Many of the artists are performing before an audience for the first time since the pandemic began months ago. Needless to say some were apprehensive...but all are extraordinarily grateful to the Artistic Director of the Festival, Stanisław Leszyński, for his courage and perseverance shown in mounting this festival against the odds in the present ghastly circumstances with a 'socially distanced' audience

Photographs by Wojciech Grzędziński/NIFC

* * * * * * * * *

21:00 August 31 Warsaw

Philharmonic Concert Hall

Piano recital

Yulianna Avdeeva piano

In Poland any mention of Yulianna Avdeeva is bound to generate intense and passionate discussion. As those of you who are familiar with my account of her winning the 16th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw in 2010, you will know of my strong conviction from the very outset that she would win. My opinion of her brilliance is not shared by all in Poland - I simply cannot understand this but then again I am not a Polish melomane.

In the storm of protest that followed this decision I could not agree more with Kevin Kenner, Second Prize winner at the Warsaw Competition in 1990 (no First Prize was awarded in that year) and a jury member in 2010 - a pianist whose musical judgment concerning Chopin I have the utmost respect for. In an interview for news.pl he justified the decision in the following words:

“Avdeeva has a very deep understanding of the score, the kind of relationship to the score which no other pianist in this competition had. She looked into the score for her creative ideas. It was the source of virtually everything she did and she was also one of the most consistent competitors throughout the event,” he said.

She has developed tremendously since her competition victory. Her fine tone and refined touch seduced the ear from the moment she touched the Steinway. Avdeeva brings an intellectual seriousness and tremendous authority to her playing. With Chopin, her search for artistic and musical truth within the notated score is clear. She brings a self-consistent, fully integrated vision of the composer to us, which, irrespective of one's personal view of her Chopin interpretations, Chopin himself or the instruments at his disposal, creates an 'authentic' and deeply rewarding coherent conception of his music. My word there are certainly many Chopins! We each have our own and those of us who love his music will defend our personal opinion to the death with a passion perhaps not given to any other composer.

To be honest

I could not wait to hear the development of one of the most mature, stylish and

musically perceptive pianist of the competition, she who presents Chopin

as a grand maître of the keyboard. After all Chopin himself,

that Ariel of the keyboard, liked above most of his pupils, the

'masculine' playing of his music by the heavyweight German pianist and composer

Adolf Gutmann (1819-1882), much to everyone's confusion at the time.

Fantasia

for Piano in G minor Op.

77

Avdeeva first performed, as possible a prologue to the 'Eroica Variations', the rarely heard Fantasia in G minor Op. 77 (1809). Beethoven’s powers of improvisation were legendary. As Czerny recalled: 'His improvisation was most brilliant and striking. In whatever company he might chance to be, he knew how to produce such an effect upon every hearer that frequently not an eye remained dry, while many would break out into loud sobs; for there was something wonderful in his expression in addition to the beauty and originality of his ideas and his spirited style of rendering them. After ending an improvisation of this kind he would burst into loud laughter and mock his listeners for the emotion he had caused in them. ‘You are fools!’, he would say.'

This fantasia is a quite extraordinary cascade of glittering, virtuosic pianistic fragments one can imagine Beethoven tossing aloft and aside in an energetic improvisatory style. I once saw a piano of his in a museum, I think in Bonn, where some of the ivories on the keyboard had been worn down to the wood! An absolutely astonishing work I had never before heard until earlier this month at Duszniki Zdrój.

Avdeeva gave

us in Warsaw and even more than previous glistening account of this rather

bizarre, not particularly attractive, work with a spontaneous sense of

improvisation, glittering tone and sparkling articulation. With full emotional commitment

she 'made something of it' and created the distinct impression of Beethoven's incredibly

whimsical and mercurial mind. This was offered as a prologue to the great work

that followed.

15 Variations

and a Fuge in E flat major on an Original Theme, Op. 35 “Eroica Variations” (1802).

One can only imagine the extraordinary impact on contemporary listeners of the opening fortissimo E-flat major chord (such a powerful identity statement of 'I compose therefore I am') followed immediately by pianissimo reveries on the Basso del Tema which organically grows into the theme proper.

The theme of the variations was also used in the Finale of Beethoven’s ballet The Creatures of Prometheus (1801), in the Contradanse, WoO 14 No. 7 for orchestra (1802) as well as of course, the Finale of the Third Symphony Op. 55, the 'Eroica' (1804) and its gestation, fraught with disillusionment. The opening gesture in the First Movement of the 'Eroica' Symphony uses a chord that is almost the same as the opening chord of the piano variations. Leonard Bernstein referred to the Eroica Symphony’s opening as 'whiplashes that shattered the elegant formality of the 18th Century.'

The pianistic technical innovations in this pianoforte work make it quite revolutionary and uniquely demanding for the pianist, perhaps the reason it is not often performed in concert despite its iconic status. On this occasion in Warsaw Avdeeva gave us an interpretation of 'heroic' masculine strength which never felt excessive, rather richer and more noble than previously. Each variation had its own style, identity, life, colour and sound with her usual tremendously authoritative command of the keyboard. The magnificent, energetic Fugue (tremendously difficult) which crowns the work was again powerfully and convincingly expressed by Avdeeva with minimal pedal. As Angela Hewitt notes of the conclusion of the piece, when the first four notes of the theme are condensed into increasingly short note values, 'One can imagine with what relish Beethoven himself would have played it!'

However for me it was the actual overwhelming nature of this music that preoccupied my mind and heart - surely all one can ask of a pianist as the conduit of the composer's musical intentions and inspiration. Of course, as is far too often the case with me, and may I add, desperately unfair, I had brain echoes of a monumental performance of the work given in 1980 in the Royal Festival Hall in London by Emil Gilels. One of my greatest musical experiences.

I am full of

admiration for Yulianna Avdeeva who ignored the risks of this frightful

pandemic and made the journey after a long period 'off stage' to rather remote

Duszniki Zdroj and later to Warsaw, purely out of love of these two festivals

and the music and associations this small spa and capital city has with

Fryderyk Chopin.

Pictures at an Exhibition

Modest Mussorgsky by Victor Hartmann

This piece is a portrait of a man walking around an art exhibition (the pictures painted by Mussorgsky’s friend, the artist and architect Viktor Hartmann). The composer is reminiscing on this past friendship now suddenly and tragically cut short when the young artist died suddenly of an aneurysm. The visitor walks at a fairly regular pace but perhaps not always as his mood fluctuates between grief and elated remembrance of happy times spent together. The Russian critic Vladimir Stasov (1769-1848), to whom the work is dedicated, commented: 'In this piece Mussorgsky depicts himself "roving through the exhibition, now leisurely, now briskly in order to come close to a picture that had attracted his attention, and at times sadly, thinking of his departed friend.'

The Russian poet Arseny

Goleníshchev-Kutúzov, who wrote the texts for Mussorgsky's two song cycles, wrote

of its reception: There was no end to the enthusiasm shown by his devotees; but many

of Mussorgsky's friends, on the other hand, and especially the comrade

composers, were seriously puzzled and, listening to the 'novelty,' shook their

heads in bewilderment. Naturally, Mussorgsky noticed their bewilderment and

seemed to feel that he 'had gone too far.' He set the illustrations aside

without even trying to publish them.

Avdeeva gave

us a powerful and idiomatic interpretation of the work with great moments of virtuoso

pianism. Many 'pictures' were painted in vivid and imaginative colours. However,

at times I felt more expressiveness would have relieved her brilliant literal

depiction of some 'pictures' or portraits. Perhaps she could have given us slightly

more breathing space between the depictions which would

have assisted the 'listening wanderer' to recover after such a demanding excursion

through the gallery.

The suite of pictures begins at

the art exhibition, but the viewer and the pictures he views dissolves at the

Catacombs when the journey changes its nature. To decide on the tempo for the Promenade

is always a challenge for the

pianist. I personally wander far more slowly around art galleries or rove in my

imagination, than some pianists. The art exhibition was of Hatmann's

drawings and watercolours (not strong oil paintings) and I feel this

should be considered when approaching the dynamic range of any performance in

order to avoid undue, declamatory heaviness.

Suite of Movements

Promenade

The tempo I felt slightly too fast for a man walking

around an art gallery, even a gallery of the mind, wandering in scenes that flooded his memory

The Gnome Avdeeva presented him as jagged and

unpredictable in unsettling halting, truncated rhythms

Promenade Sensitively and dynamically reduced to match the following painting

The Old Castle Avdeeva presented melancholic reminiscences of the faded glory of battles past, victorious and defeated in songs sung by a troubadour

Promenade

Tuileries (Children's Quarrel

after Games) Retains the innocent cruelty of such

quarrels in the playground.

Cattle Avdeeva skilfully presented these 'Polish' oxen pulling a heavy wagon passing by, ponderously close and odiferous, then moving off along the unmade track into the distance

Promenade

Avdeeva presented a thoughtful, dynamically graded transition

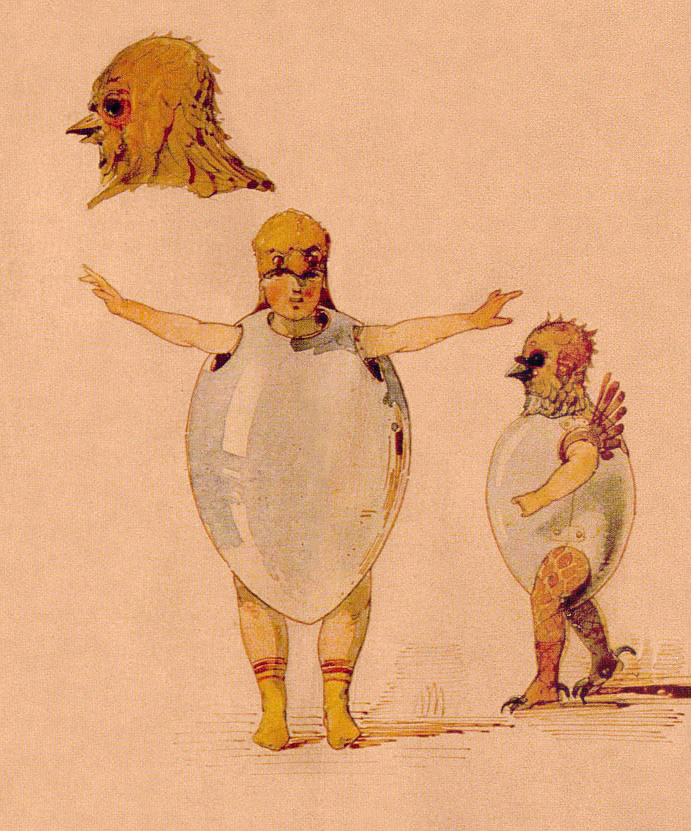

Ballet of Unhatched Chicks

Avdeeva presented a scintillating depiction of Hartmann's design

for the ballet Trilby - the imagined nervous movements of canary chicks.

"Samuel" Goldenberg and "Schmuÿle"

Two Polish Jews, Rich and Poor - Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuÿle - were depicted

'Rich'

'Poor'

Promenade

Limoges. The Market (The Great News)

Mussorgsky indicating excitable argumentative

provincial market life to perhaps contrast more strikingly with death in the

next depiction. Avdeeva sparkled with rural invective here.

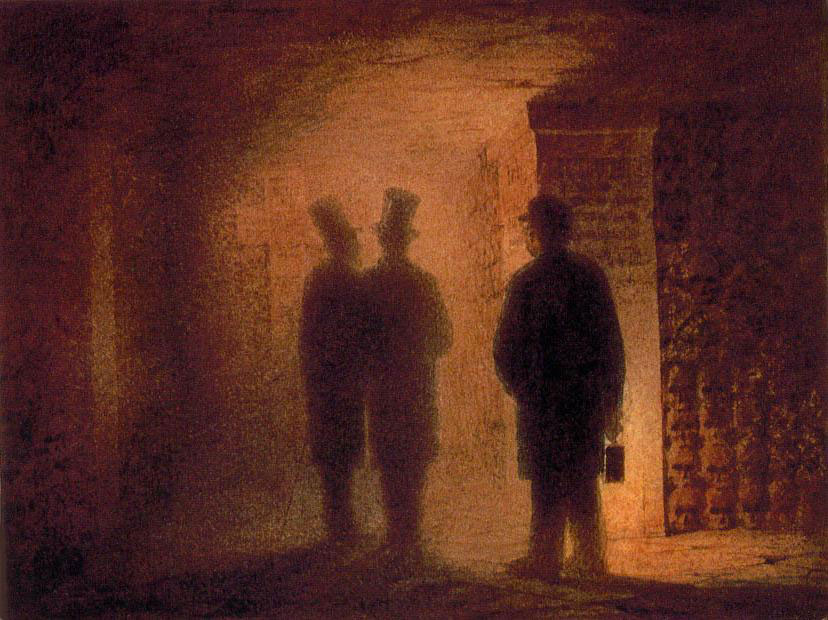

Catacombs (Roman Tomb) - With the Dead in a Dead Language

Avdeeva presented the movingly atmospheric, melancholic ambience of darkness,

skulls, silence, mould and decay. I remember this after visiting them myself when

living as a child in Rome many years ago

'Catacombae' and 'Cum mortuis in lingua mortua' from Mussorgsky's 'Pictures at an Exhibition'

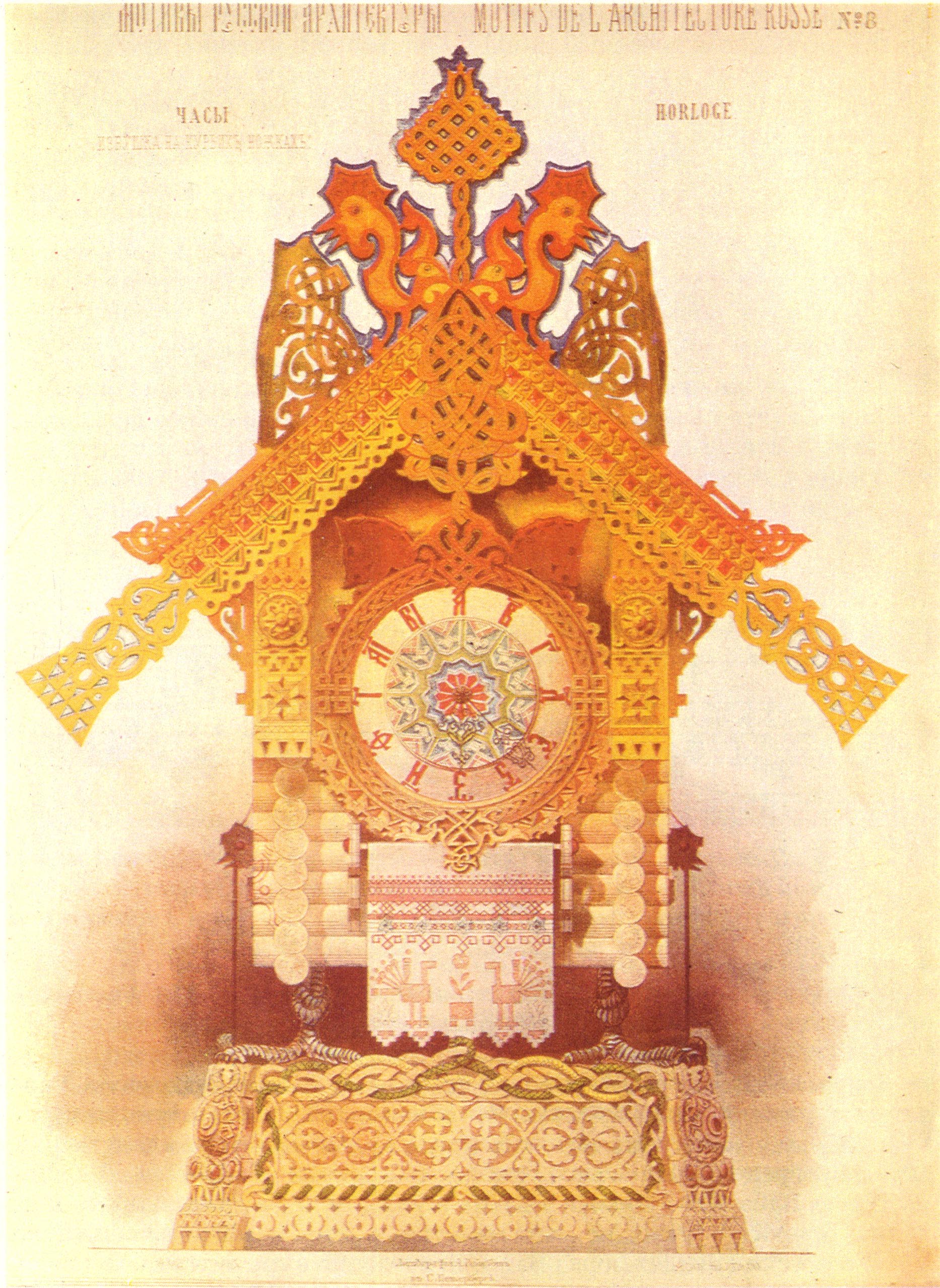

The Hut on Hen's Legs (Baba Yaga)

Avdeeva painted the portrait of a truly nasty

and frightening fantasy creature. Hartmann's drawing depicted a clock in the

form of the ghastly Baba Yaga's hut perched on fowl's legs. Mussorgsky added the witch's

flight in a mortar - possibly created following a tormented dream.

The ghastly witch Baba Yaga

The Bogatyr Gates (In the Capital in Kiev) or 'The Great Gate of Kiev'

Avdeeva constructed a monumental gate of power and majesty with great nobility of tone to sculpt massive deliberation at the conclusion. She sounded completely convincing in her depiction of the joyful celebratory peals of Orthodox bells and carillons. I felt this to be by far the most expressive and persuasive of her 'pictures'.

Her performance was given a standing ovation and was tumultuously received by the 'distanced' audience.

As a first encore, a refined and sensitive Chopin Nocturne in F major Op.15 No.1.

For her second, singularly appropriate in view of the

date, it being the eve of the shelling of Westerplatte and the outbreak of the

Second World War, a majestically performed Chopin Polonaise in A-flat major Op.53

21:00 Warsaw August 30 Philharmonic Concert Hall

Recital of Songs

Christoph Prégardien tenor

Julius Drake piano

I had heard

this fine musician and subtle lyric

tenor Christoph Prégardien last year at this festival elevating Moniuszko songs

to the level of true art, as well as heart-rending songs by Duparc. A deeply memorable

musical experience. Before that, in June 2017, at the Frauenkirche in

Dresden, I heard him sing madrigals and operatic excerpts with his son Julien

to commemorate the 450th birthday of Claudio Monterverdi. They were accompanied

by Anima Eterna Brugge conducted by Jos van Immerseel. One can imagine I

anticipated this recital of Beethoven and Schubert songs with great pleasure.

Concerts

are never real music, you have to give up the idea of hearing in them all the

most beautiful things of art.' Chopin said to one of his students (Chopin: Pianist and Teacher:

As Seen by His Pupils Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger). Far be it from

me to contradict Chopin, but this was certainly not the case in the song

recital I attended this evening.

Beethoven once commented 'I don't like writing songs' and was not prolific in this genre. I must admit to be vastly more familiar with his chamber, piano, opera and symphonic output than his songs. Many of them were quite new to me apart from being of course sung in German. However I did have a couple of favored songs, mostly about the travails of love arising from his fraught relationship with the 'immortal beloved' and other tragic losses. Such negative occurrences assailed Beethoven as deeply and bitterly as the rest of us

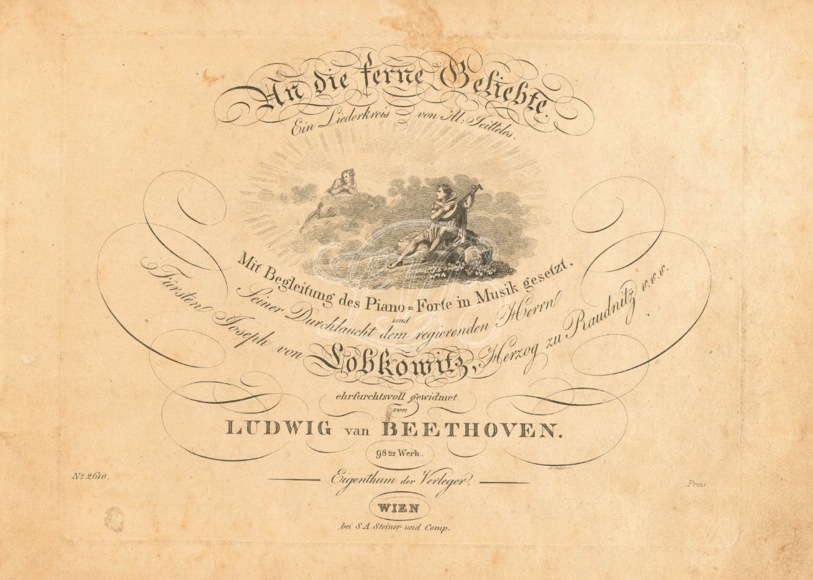

Beethoven was the first composer to arrange songs in cycles. These six short poems are arranged as a group to follow each other attacca. The poet believes his songs can reduce the separation between them. Recent research indicates the cycle may possibly be dedicated to the Beethoven's beloved patron Prince von Lobkowitz who was recently bereaved having lost his wife. On the other hand Beethoven may be envisaging a yearning for his own 'immortal beloved'.

They were sung radiantly, incomparably passionately with deepest yearning and incandescent emotion by Prégardien. He was accompanied on the piano by Julius Drake, arguably the most outstanding and eminent song accompanists performing in the world today.

I sadly do not have the German language, but one really must read the superb translations of these sensitive love poems of loss written by the medically selfless Austrian physician and writer Alois Jeitteles (1794-1858). Subtle and thoughtful translations by Richard Stokes, Professor of Lieder at the Royal Academy of Music and award winning translator, are available for each poem in the cycle here: https://www.oxfordlieder.co.uk/song/1048

An die ferne Geliebte ('To the departed beloved')

Auf dem Hügel sitz’ ich, Op.98 No. 1

Wo die Berge so blau Op.

98 No. 2

Leichte Segler in den

Höhen Op. 98 No. 3

Diese Wolken in den

Höhen Op. 98 No. 4

Es kehret der Maien, es blühet

die Au Op. 98 No. 5

Nimm sie hin denn, diese

Lieder Op. 98 No. 6 (Such

a deeply affecting and passionately delivered song)

With Schubert songs it is all to easy to gloss over the poetry to concentrate solely on the music. Often the poet knew the composer and there was a cross-fertilization of inspiration. His life frustrations, crises and literary appreciation attracted him to certain poets. One might be surprised to learn there are some 110 poets Schubert set to music ranging from Metastasio (1698-1782) to Heinrich Heine, even touching upon Petrarch, Shakespeare and the Greeks. there are seventy-four Goethe Lieder and forty-four Schiller Lieder. He was always looking out for new inspirational poetic material for his Lieder. Many German and Austrian poets, famous in their lifetimes and taken up by the composer, have faded into undeserved oblivion. The composition of Schubert songs depends on the availability of lyric poetry and a sublime renaissance of lyricism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Criticism today of the quality of the poetic choices Schubert made is common but critics of his period often possessed quite a different judgement. He was often praised for his choices and was proud of his own assessment of their quality. Yes, he may have begun with the sentimental Hölty, Matthisson, Salis-Servis and Kosegarten but moved 'up' to Goethe, Schiller, Wilhelm Müller, Walter Scott and Heine. The pathological poet Ernst Schultz ('obsessed with love for two women who did not return his love' and who recorded these travails in a diary) was quite familiar to Schubert. The Johann Mayrhofer poems may well have inspired harmonically advanced music wherein Schubert anticipates Wagner. Poetic images also inspired profound music. As I often mention in my reviews, a deep knowledge of literature and its cultural significance is needed to fully understand the thoughts that inspired so many nineteenth century composers.

[Much thanks from me to Susan Youens for her essay Schubert and his Poets:Issues and Conundrums]

Please read to escape for even a moment the ubiquitous golden calf and social reductionism of our age.

Schwanengesang (Swan Song) (1828)

Heinrich Friedrich Ludwig

Rellstab (1799-1860) was a German poet

and music critic. He had considerable influence and power over what music could be used for German nationalistic

purposes in the mid-nineteenth century. Because he had 'an effective

monopoly on music criticism' in Frankfurt and the popularity of his

writings, Rellstab's approval would have been important for any musician's

career in areas in which German nationalism was present.

The first seven songs of Franz

Schubert's Schwanengesang have words by Heinrich Rellstab (1799-1860)

Liebesbotschaft, No. 1

Kriegers Ahnung No. 2 (D.

957 ) (Such a dark, melancholy

beginning)

Frühlingssehnsucht No. 3

(D. 957 )

Ständchen No. 4 (D. 957 )

(superb without the slightest

hint of kitsch in this famous song)

Aufenthalt No. 5 (D. 957

)

In der Ferne No. 6 (D.

957 ) (Powerful and deeply

considered with a strong sense of rebirth)

Abschied No. 7 (D. 957 ) (gentle and blithe)

Short pause

The German poet Heinrich Heine

(1797-1856) wrote the poems for the last six songs.

Der Atlas No. 8 (D. 957 )

(Violent resistance to destiny

in a magnificent, theatrical conclusion)

Ihr Bild No. 9 (D. 957 ) (a powerful, visionary, charismatic atmosphere)

Das Fischermädchen No. 10 (D

957)

Die Stadt No. 11 (D. 957

) (so bleak a conclusion my

blood froze in my veins)

Am Meer No. 12 (D. 957 ) (desperately melancholic yet passionate)

Der Doppelgänger No. 13

(D. 957 ) (Impenetrably dark

and apprehensive)

For affecting translations of the songs that make up Schwanengesang click on this link:

https://www.oxfordlieder.co.uk/song/928

They are translated by Richard Wigmore. He read modern languages at Cambridge and studied music at the Guildhall School of Music and the Salzburg Mozarteum.

There is nothing left to say about this sublime and moving performance of Schubert songs that raised us from this earthly coil by these two great artists. A memorable life musical experience.

I take leave to quote Shakespeare from Henry V Act IV and the St. Crispin's Day speech of the King

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here

At the conclusion of this

recital, Christoph

Prégardien and Julius Drake thanked

the audience profusely from the stage and the Artistic Director of the festival,

Stanisław Leszczyński, for providing them with the opportunity to perform.

Julius Drake said that since the beginning of the pandemic it was as if they

had had part of their body removed, like 'a limb cut off' as he graphically

expressed it.

They then movingly performed the last song Schubert ever wrote, the last song of the Schwannengesang, Die Taubenpost to words by Johann Gabriel Seidel - a surprisingly blithe and tender song. https://www.oxfordlieder.co.uk/song/1047.

The second encore was Wonne Der Wehmut (Delight in Melancholy) a song by Beethoven omitted from the beginning of the recital (the lack of an intermission owing to the pandemic restrictions prevented the singer from performing the first three programmed Beethoven songs during the official recital) https://www.oxfordlieder.co.uk/song/3172 translated by Richard Wigmore.

An enthusiastic, seemingly never-ending standing ovation for a recital of the highest in musical art that restored one's faith in the civilized values of humanity.

21:00

August 29 Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Chamber

concert

Cristina Esclapez historical

piano

Lorenzo Coppola clarinet

Kristin von der

Goltz cello

This was a

particularly fascinating concert, not least of all because of the adventurousness

of the musicians involved, their instruments and the music they chose to play.

'Music lovers today do not always realise what an important element of the nineteenth-century repertoire was composed of transcriptions – adaptations of original works for different forces (sometimes produced by their composers, but more often by publishers wishing to multiply their profits and by virtuosos seeking attractive new repertoire).'

This remark by Piotr Maculewicz, of essential relevance to this concert, is taken from the excellent programme notes accompanying this unique event which I suggest you read closely https://festiwal.nifc.pl/en/2020/kalendarium

Lorenzo Coppola, the clarinettist,

spoke to us directly, most engagingly and entertainingly from the stage at the

beginning of the concert. He profusely

thanked the National Chopin Institute for the rare offer of an opportunity

to play with a live audience during the pandemic. He then invited us join him

in realizing a 'musical dream' as a consolation to the ghastliness surrounding us.

Clearly he is one of life's communicators. He continued to introduce each work

in an informative and sometimes emotional manner, which was immensely relaxing

for the audience. The programme was in a carefully designed interpretative arc

from bucolic opera buffa to the most profound musical utterance.

Trio in B

flat major, Op. 11

In his chat to

us that delightfully opened the programme, Coppola reminded us that Beethoven played the

viola as a young musician in a theatre orchestra and would have had extensive

experience of music for the opera. He then demonstrated his rare comic actor

ability by demonstrating the type of character certain music would illustrate

in various moods. Love, jealousy, the plaintive complaining lover and piracy. In a demonstration of opera

buffa he depicted an immensely successful caricature of a drunken man.

The timbre of this ensemble with the period clarinet, the Buchholtz copy by Paul McNulty of a Polish piano of the Chopin period (his family owned one) and the rich cello made for an unaccustomed group mixture of sounds. The Allegro con brio betrayed many amusing motifs with witty repetitions and a rather comic conclusion. The Adagio was soaked in faux melancholy, sadness and yearning - the risible 'love sickness' of the plaintive, complaining lover of much poetry, literature and operetta.

The Theme (con variazioni) was almost ludicrously 'jolly hockey sticks' as we say idiomatically in English. Picture of a cartoon drunken man came to mind with the unhinged clarinet and foolish instrumental dialogues. Such jokey sections precluded a faux-serious interlude which reminded me of the instruction books for pianists detailing set musical gestures to accompany the changeable moods in silent films. The variations were on the aria ‘Pria ch’io l’impegno’ from Joseph Weigl’s opera L’amor marinaro, which mined the then popular subject of piracy. The simple, even trivial melody of the theme is of a type which the Viennese termed Gassenhauer (from ‘Gasse’, meaning ‘street’), so a catchy ‘hit’ that was hummed and whistled by everyone, hence the work’s nickname: Gassenhauer-Trio (Maculewicz). In my mind's eye I could see unsophisticated villagers enjoying themselves in the countryside, something Beethoven would surely have seen and heard at that early stage in his life.

Gretchen

am Spinnrade D118

The affecting regrets and yet ambiguous love yearning felt by Gretchen for Dr. Faust in this instrumental version of the touching Schubert song has been movingly arranged for cello and piano. Gretchen cannot forget the physical attractions of Faust, then his kiss (the wheel stops). Then the reluctant acceptance of sorrow and the despair of loss as it slowly begins to spin again. Here Schubert melds her immediate present and her Romantic past memory in a deeply affecting dual time scale. We are inexorably drawn into Gretchen's fantasy.

The sensitive Cristina Esclapez extracted a rare tone and refined touch from the Buchholtz and the image of the spinning wheel. She is clearly intimately involved with period instruments and experienced in managing their uniquely evocative yet complex qualities. The cello played by Kristin von der Goltz was rich yet balanced in timbre, emotion and sonority with the piano.

3 Fantasiestücke

for clarinet and piano, Op. 73

This was not

an arranged but original piece by Schumann. He was most interested in the

expressive capacities of the instruments rather than displaying ostentatious

virtuosity. Zart und mit Ausdruck (tender and with expression) was

replete with heartfelt, nostalgic memories and emotional yearning with

especially fine, evocative phrasing by Coppola on the clarinet. Fine, notable

balance of timbre and sonority existed between the piano and clarinet. Lebhaft,

leicht (lively, light and nimble) expressed for me the embraces of love.

There was rare musical understanding established between piano and clarinet

here, a perfect melding of timbres and phrasing. Rasch und mit Feuer (quick

and with fire) Impetuous declamations were balanced by graceful lyricism

between this perfectly balanced duo.

Esclapez has

such a seductive touch on the Buchholtz, never forcing the tone in any way,

simply utilizing the strengths of the instrument within its limited, but deeply

expressive, color and dynamic range. The

composer was always experimenting with the timbre of piano sound. A piano

of Schumann's period (he loved Clara's Conrad Graf of 1838 from

Vienna) had many varied colours, timbre and textures within the different

registers . The match with the mahogany 'woody' texture of the period

clarinet formed a charming and telling romantic musical relationship.

‘Gute Nacht’ from the song cycle Winterreise, D 911

The elegiac introduction of the tender and dark story given by Coppola to this song, arranged for clarinet and piano by Carla Bärmann, was almost more suggestive than the music itself when it came. The sensitivity to the literature expressed through the medium of sound is something all instrumentalists should aspire to. The clarinet and piano expressed the deep sadness contained within the language in a manner inspiring to poetic flight.

Good Night

I arrived a stranger,

a stranger I depart.

May blessed me

with many a bouquet of

flowers.

The girl spoke of love,

her mother even of

marriage;

now the world is so desolate,

the path concealed beneath snow.

I cannot choose the time

for my journey;

I must find my own way

in this darkness.

A shadow thrown by the moon

is my companion;

and on the white meadows

I seek the tracks of deer.

Why should I tarry longer

and be driven out?

Let stray dogs howl

before their master’s

house.

Love delights in wandering

–

God made it so –

from one to another.

Beloved, good night!

I will not disturb you as you

dream,

it would be a shame to spoil your

rest.

You shall not hear my footsteps;

softly, softly the door is

closed.

As I pass I write

‘Good night’ on your gate,

so that you might see

that I thought of you.

English Translation of a poem by Wilhelm Müller © Richard Wigmore

The performance was as sensitive and full of the heartbreaking, tragic sensibility Schubert laid before us during this legendary song cycle. An extraordinary musical moment of heightened reality in life.

Andantino from the

Piano Sonata in A major, (D.

959)

I could not

think of a more fitting pendant to the arrangement just heard than this

melancholy recognition of the unavoidable approach of the icy embrace of death.

Sensitive heartbeats sound as the reaper advances irresistibly, then the

inevitable knock at the door. The Buchholtz played by Esclapez was as fragile as

the soul of Schubert. Yet there were explosions of anger at this fatalistic, inescapable

destiny. One could feel and see the falling of tears of despair in the repeated

notes. So deeply affecting was her creation, I did not want crude applause to erupt and brutally

shatter the charismatic atmosphere of humanity facing destiny, the inevitable

fate facing us all.

Trio in G

minor, Op. 8 (arranged for

clarinet, cello and piano by Lorenzo Coppola) (1829)

A sketch of the young Chopin by Eliza Radziwill 1826, probably drawn at the hunting lodge of Prince Antoni Radziwill at Antonin, Poland.

From the

stage Coppola winningly engaged us again. Even François Couperin in his L'Art

de Toucher le Clavecin suggested the player sit at an angle to the audience

and tastefully engage them with a smile at telling moments. Coppola felt that

the Trio was an 'operatic' work, indicating that the third movement Adagio.

Sostenuto was possibly inspired by Bellini and the fourth Finale.

Allegretto by popular 'street music'.

The eminent Polish pedagogue Mieczysław Tomaszewski writes of this substantial work: 'For Chopin, the Trio in G minor turned into a task, a challenge and an adventure all in one.' In this early chamber piece of Chopin written when he was 18, the opening Allegro con fuoco with the unusual timbre of the clarinet, Buchholtz period piano and cello made for a novel and sensually attractive combination. I immediately found the arrangement the substitution of clarinet for the original violin most effective and in keeping with the less stringent instrumental musical philosophy of the day. A different soundscape seemed to open where the influence of Beethoven on the composition of this movement was made clear. One can hear the influence of Schubert and even Hummel in the work. There were many dramatic silences and revealing phrases. I found that the different timbre aroused unaccustomed emotions - not superior but different - perhaps less emotionally tense than the original with violin.

The Scherzo.Vivace had moving cello counterpoint that blended seamlessly with the ensemble sound to create an atmosphere of great charm. One recalls Chopin wrote it at the Antonin hunting lodge for the fine aristocratic cellist and composer Prince Antoni Radziwiłł and his daughters. Chopin dedicated it Radziwiłł but it was written as a study piece for his teacher Józef Elsner. The clarinet added a rather dreamy, less serious , almost salon feeling to the instrumental dialogues of this movement. They captured the feeling of a country dance with a little humour. The Adagio. Sostenuto lyric song, as Coppola mentioned, possibly influenced by Bellini, sounded extremely beautiful on the clarinet, close to the human voice. A quite different feeling to the tessitura of a violin. In a way I missed the soulful yearning of the violin in this movement. The clarinet was a different experience. The ultra pianissimo conclusion I found haunting and hypnotic.

The rondo Finale. Allegretto was like a fresh spring breeze that blew away the clouds of melancholic introspection. There were references to the exuberant krakowiak dance in the jolly instrumental dialogues. In the meantime, we have been served a number of episodes, the most characteristic of which resembles a Ukrainian Cossack dance. The cello remained rich and passionate, the piano refined, effortlessly binding the ensemble together. The clarinet gave the rustic theme a true village character which was so engaging and pleasurable.

Tomaszewski further observes : 'The

only problem is that the Trio was written in a style that is rather un-Chopin.

Or perhaps it would be more appropriate to say: a style that is different to

what we tend to associate with Chopin.' Even Schumann, always a

enthusiast for the compositions of Chopin, rhetorically commented of this great

piece of Polish chamber music: ‘Is it not as noble as one could

possibly imagine? Dreamier than any poet has ever sung?’

This was a highly successful and civilized concert which illuminatingly taught us how flexible instrumentation can be applied to works that are not in the least inviolable but indeed benefit from such variety. A remarkable concert of great sensitivity which brought unaccustomed sonorities to familiar works.

As an encore, a deeply expressive and moving arrangement of the Chopin Prelude in E minor Op.28 No.4 whose sheer beauty, poetry and unexpected simplicity brought the audience to the verge of tears.

21:00 August 28 Warsaw Philharmonic Concert

Hall

Piano recital

Gabriela Montero piano

Sarcasms, Op. 17 (1914)

This extraordinary polytonal essay in

the grotesque was brought off with great authority by Montero. Prokofiev composed Sarcasms between

1912 and 1914. He rejoiced in the controversy provoked by such extravagant

compositions and performances, and

the subversive ironical element contained within this

musical criticism of the Russian government. In so many ways

Prokofiev was a romantic composer. The ominous threats contained and were

successfully revealed by Montero.

Why one would wish to begin a recital with Tempestoso

at a fortissimo dynamic, however commandingly played, rather defeated

me. The second Allegro rubato is rather unusual, almost aleatoric music.

Her fantastic keyboard performance of the Allegro precipitato reminded

me of the final tumultuous movement of the 7th Sonata. The meaning of the next

title Smanioso in Italian was

unknown to me but now I realize it was 'restless' or 'agitated'. I felt Montero

rather unyielding in this work. The final Sarcasm is marked Precipitosissimo.

In 1941 Prokofiev reflected on the fifth Sarcasm: ‘Sometimes

we laugh maliciously at someone or something, but when we look closer, we see

how pathetic and unfortunate is the object of our laughter. Then we become

uncomfortable and the laughter rings in our ears, laughing now at us.’ Of

this, the Russian virtuoso Konstantin Igumnov observed:

‘This is the image of a reveller. He has been up to mischief, has broken

plates and dishes, and has been kicked downstairs; he lies there and finally

begins to come to his senses; but he is still unable to tell his right foot

from his left.’

Carnaval Scènes

mignonnes sur quatre notes Op. 9

We then turned to Schumann's Carnaval Op.

9 (1833-35). It consists of 21 short pieces representing masked pleasure

seekers at Carnival, the festival before Lent. Schumann paints musical

portraits of himself and his friends as well as characters from the commedia

dell'arte. At this high level of keyboard proficiency and pianistic art,

it was of course technically a very fine performance. However I felt, despite many movements full of

moving poetry and sincerity, Montero tended to rush the work at times so that

it failed to express sufficiently strongly the contrasts of the puzzling,

violent, idiosyncratic, tender and capricious side of Schumann. The fast tempi she

adopted in contrast to the beautiful, more reflective passages she played, the breathlessness of her

phrasing, became problematical for me. Overall I did not feel she gave it the

great creative ‘literary’ characterization it requires. Much of the

polyphonic internal detail and colour tended to be absorbed. Although emotionally rhapsodic

at times, the highly strung tempo made the work somewhat inaccessible to the

listener. The waltz rhythms were attractive and beguiling but more breathed

expression would have been so welcome. These aspects are reflected in the

mercurial moodiness of the marvellous self-portraits (the divided personality

of the Schumann the man in Florestan and Eusebius)

and the colourful array of characters. A quotation from Macbeth is apposite:

The pianist requires an almost incandescent imagination to do justice to the genius of this composer. In Carnaval the secrets of the Sphinxes are intelligible and expressed by only 'the happy few' among pianists.

Two improvisations

Her immense international reputation is unsurpassed in the art of creative classical improvisation. All the great keyboard composers from the Virginalists - harpsichord composers such as Froberger, the Couperins, Scarlatti to Handel and Bach - composers for the piano such as Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann - were all natural improvisers and performed largely their own music. The idea of devoting your life to mastering an instrument and performing music written for it by others is a relatively recent phenomenon in the history of music.

She spoke to the audience rather intimately

about the pandemic and how happy she was to be performing at last! This

was her first public recital since March

(perhaps explaining her nervous approach to Schumann). She told us she would

play two contrasting improvisations. The first would be her intimate thoughts

and personal reaction to the pandemic at home in Venezuela. The second as a musical consolation to the pandemic. Both were low key and affectingly simple in their

attractiveness.

Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor Op. 36

Two improvisations

As is her usual practice, she requested sung

themes of local character from the audience on which to improvise.

The first was a Polish folk song entitled Ty pójdziesz górą (You Travel Higher) sung by a gentleman in the audience from the stalls.

There

are a number of versions of this song but both deal with the impossibility of love

between two people owing to circumstances beyond their control. Her fertile musical

imagination and rare ability to realize this on the keyboard in a classical

idiom never ceases to astonish and move me.

You will go up, you will go up

And I'm in the valley

You will bloom with a rose, you

will bloom with a rose,

And I am a viburnum.

You will go along the road ,

you will go along the road the way

And I will go through forests,

You wash with water, you wash

with water,

And I in tears.

You will be a lady , you will

be a lady

At the great court,

I will be a priest, I will be a

priest

In a white monastery.

And when we die, when

we die,

We order ourselves

Golden letters, golden letters

Carved on the grave.

Those who will be going

past there

Will read

United love, united love

lies in this tomb.

The second theme was sung by a lady from the balcony.

It was a song by the Polish national composer Stanisław Moniuszko

entitled Wieczorna pieśń (Evening Song). It concerns an unhappy young lady

tired of working in the fields all day, spoiling her hands and complexion and clearly

yearning for a more colourful life.

Montero clearly loved this theme and improvised

on it magically for a surprisingly extended period - possibly ten minutes - in

various styles (including jazz).

Over the night dew

flow

resonant voice

let

your echo spread

where

is our hut,

where

is the old mother

bustling

around supper.

Tomorrow

is a public holiday,

the

cornfield is not harvested

let

it mature by tomorrow,

let

the wind playful,

let

the grasshopper,

let

the lark sing here.

It's

close, close

a

bonfire

a

weary heart is merry;

hard-working

there

my

mother will ask me:

"How

much have you reaped in the field?"

Mother,

I am young,

I

feel sorry for my hands,

I

don’t want to burn my face!

the

work did not go well

the rain was in the way

and my maiden dumka!

A most enjoyable concert by a pianist who is popular in Poland and in command of rare natural gifts that many young pianists should aspire to - namely the uncommon ability to creatively improvise.

17:00

August 28 Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Piano

recital

Dmitri Alexeev piano

This great

pianist and pedagogue scarcely needs any introduction to audiences - his

musical maturity and eminence is renowned and celebrated throughout the world.

Novelette

in F major, Op. 21 No. 1

Schumann intended the eight pieces of his Noveletten, Op. 21 (1838) to be performed as a group, though they are often successfully performed separately. These "tales of adventure," as the composer referred to them, provide a completely representative example of the composer's keyboard style. No. 1 in F major alternates a staccato March with a flowing legato passage within its five sections. Alexeev opened with huge tone and great emotional commitment. His cantabile of the melody was full, rounded and singing. However, he enlarged this work to almost 'heroic' dimensions which am not sure is justified.

Kreisleriana Op. 16

He then embarked on one of my favourite

works of romantic piano literature Kreisleriana Op. 16 also by

Schumann. To precede this work by the Novelette showed

interesting musical planning foresight.

Madness or

insanity was a notion that throughout the composer's time on earth, simultaneously attracted and repelled Schumann. At the end of his life he was

cruelly to fall victim to it. Kriesleriana was presented

publicly as eight sketches of the fictional character Kapellmeister Kreisler, a

rather crazy conductor-composer who was a literary figure created by the

marvellous German Romantic writer E.T.A. Hoffman. The piece is actually based

on the Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier and also the form of an

inventive grotesque satirical novel Hoffmann wrote with the remarkable, translated

title: Growler the Cat’s Philosophy of Life Together with Fragments of

the Biography of Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler from Random Sheets of the

Printer’s Waste.

The fictional author of this novel Kater Murr (Growler the Cat) is actually a caricature of the German petit bourgeois class. In a theme rather appropriate in our times of gross financial inequalities, Growler advises the reader how to become a ‘fat cat’. This advice is interrupted by fragments of Kreisler’s impassioned biography. The bizarre explanation for this is that Growler tore up a copy of Kreisler’s biography to use as rough note paper. When he sent the manuscript of his own book to the printers, the two got inexplicably mixed up when the book was published. Such devices remind one of Laurence Sterne in that great experimental novel Tristram Shandy.

Schumann was particularly fond of Kreisleriana. He was attracted to composing a works in

‘fragmented’ form in the structural manner of this novel. The use of the device

of interrelated ‘fragments’ (as the nineteenth century

termed what we might refer to as 'miniatures') was employed by the Romantic Movement in

poetry, prose and music. Kreisler is a type of Doppelgänger for

Schumann. This was a favourite concept for the composer, who divided his own creative

personality between the created characters of Florestan and Eusebius. With the

unpredictable Kreisler as his alter ego, Schumann was able to indulge the

dualities of his own personality. The music swings violently and suddenly

between agitation (Florestan) and lyrical calm (Eusebius), between dread and

elation. The episodes in the piece describe Schumann's emotional passions, his divided

personality and his creative art. His tortured soul alternates with lyrical

love passages expressing the composer’s love for Clara Wieck. He used and

transformed one of her musical themes in the work.

1838 was a disturbed

time for Schumann. His marriage to this 'inaccessible love', the piano virtuoso

Clara Wieck, was a year ahead. At this time they were painfully petitioning the

courts for permission to marry and ignore her father's cruel social class objections

to the connection. They had known each other for ten years before their eventual

marriage in 1840. During this turbulent period of frustration, Schumann’s

compositions evolved in complexity. Their unbridled emotionalism and adventurous

structure confused musicians, audience and critics alike.

He originally

intended to dedicate the work to Clara, but

wishing to avoid more calamitous situations with her father, eventually

dedicated it to his friend Fryderyk Chopin. The

polyphonic nature of the piece may have reflected a deep understanding of

Chopin's own style. The Polish

composer merely commented on the cover design of the

score left on his piano. Even Clara, on first acquaintance with the work, wrote:

'Sometimes your music actually frightens me, and I wonder: is it really true

that the creator of such things is going to be my husband?' Even Franz

Liszt was challenged finding the work 'too difficult for the public to

digest.'

This great masterpiece of emotional and structural complexity, expresses

much of the quixotic mercurial temperament of Schumann's personality and

the literary elements of the story. The French literary theorist and

Schumann-lover Roland Barthes interestingly observed that Schumann composed

music in discrete, intense 'images' rather than as an evolving musical 'language',

like a succession of frames in a film. The composer was experimenting with the timbre of piano

sound. Without wishing to appear a 'crank', I feel it necessary to say that on

a piano of Schumann's period (he loved Clara's Conrad Graf of 1838 from

Vienna) the varied colours, timbre and textures of the different registers

suited the contrapuntal nature of composition. This would have been rather more

obvious on the older instrument than on the modern homogenized Steinway.

Alexeev cultivated a poetic and singing cantabile of great sensitivity, alluring colour, restrained tone and lyricism. His articulation in some passages was superb. The richness of his tone was seductive, never harsh but the sheer immensity and impulsive, even excessive contrast could hardly have been envisaged by Schumann on his instrument. Alexeev often adopted too fast a tempo (for me), often with pedal, which clouded the different voices. This meant he skated over much internal, expressive polyphonic detail. The transitions between sections, even within them, were often difficult to follow at such rapid tempi for this listener. The rhythmic jolts, accompanied by almost symphonic dynamic inflation, were rather disconcerting. Yet beautiful poetry was often present.

Alexeev was prone to being completely

taken over by his emotional involvement in the work, glossing over other considerations,

this even despite one passage marked Mit aller Kraft - with all your

strength! This was clearly a grand

performance by a grand maître of the instrument, but I think period

sound is worthy of consideration when examining the contrasting timbres and

overall comparative dynamic range of Schumann's writing for his instrument. My reaction is always coloured by Vladimir Horowitz who I consider

unsurpassed in his later interpretations of this work.

Rondo in C

minor Op. 1

Alexeev adopted a rather different approach to the customary performance style this Chopin Rondo in C minor Op. 1 (1825) is interpreted. He played it much as a charming and highly expressive salon piece with variations in tempo and rubato rather than as a glittering style brillant virtuoso work from Chopin's youth. Some may find this approach unacceptable. Of course we are now so distant from the source of this music one can only speculate how Chopin himself would have approached the performance and one might ask, is the question so relevant?

Barcarolle

in F sharp major Op. 60

View of the Island of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice (1780) Francesco Lazzaro Guardi

I am afraid I

did not warm to this performance of the Barcarolle in F sharp major Op.

60 (1845–46), this charming gondolier's folk song, sung to the swish of oars

on the historic Venetian Lagoon or a romantic canal, often concerning the

travails of love. Most of the piece oscillates gently between forte, piano and pianissimo with one fortissimo and another for the final chords. There are only subtle

degrees of heightened emotion throughout. The opening tonal mood octave Alexeev set well but slightly too strenuously. Just setting off after all. Poetically his view of the work seemed more dry than romantic and

authentically heartfelt. Disturbing yet civilized degrees

of heightened passion do occur during this outing on the

lagoon. Towards the conclusion I felt he tended to overdo

the ecstasy as do so many pianists. I will never believe this is an

explosive virtuoso work and it is almost invariably presented as such.

It was often observed that Chopin played with a much lower relative dynamic

than were are used to today i.e. forte for him was

perhaps mezzo-forte for us or even softer. This, together with

and as a result of the limitations of the instruments of the day, means the dynamic scale of the work is not gigantic. Pianissimo on a

Pleyel is the barest perceptible whisper.

Berlioz once described Chopin's own playing

'....the utmost degree of softness, piano to the extreme, the hammers

merely brushing the strings, so much so that one is tempted to go close to the

instrument and put one's ear to it as if to a concert of sylphs or

elves.' (Quoted in Rink, Sampson ,Chopin Studies 2 p.51).

Are we simply to ignore these contemporary descriptions

convinced that 'we moderns must know better'? Of course I would never suggest

imitating this type of thing in a large modern concert hall but I feel these are important considerations in terms of dynamic scale when

considering this great masterpiece.

The Young Alexander Scriabin

5

Preludes, Op. 16

Alexeev then turned to Scriabin Alexander Scriabin – 5 Preludes Op. 16

(1895). The influence of Liszt and Chopin is clear in these early works, until

perhaps 1900, when his musical voice emerges and

embraces the world of mysticism and more radical compositions.

- No. 1 in B major

- No. 2 in G sharp minor

- No. 3 in G flat major

- No. 4 in E flat minor

- No. 5 in F sharp major

The first of

the five preludes is marked Andante and presents us with a lyrical post-Romantic

theme. I was reminded of Rachmaninoff. The second prelude, marked Allegro,

begins with a broken motif which became immensely passionate with Alexeev. The

third, marked Andante cantabile, I felt lacked rather in love and

expression. Alexeev transformed the mood of the fourth, marked Lento, into

a rather moving piece. The fifth Allegretto

prelude, dispels the solemnity, bringing the set to a close with a

fleeting brightness.

Waltz in A

flat major, Op. 38

Hard for me

to say, but I was not as seduced by the glorious Valse Op. 38

(1903) as I had hoped to be. I have always seen this tender and ravishing

work of haunted yet delicate sensibility, a type of dream waltz whose harmonies

absorb into the night with perhaps, as time passes, agitated intimations or

premonitions of the coming Great War that would destroy this languishing,

civilized world. Alexeev gave my lyrical dream rather more turbulent

flavour but in gestures of total emotional commitment. Sofronitsky offers a superb interpretation of this work, a view of great sensibility.

Deux

poèmes, Op 69 (1913)

Alexeev

allowed the harmonies of the Deux poèmes, Op 69 (1913) to create dreamy,

whimsical, and capricious moods. The second Allegretto, whose ‘wild

arabesques’ were so described by a Times critic when Scriabin

played it in London the following year in 1914. The work recalls the mocking

tone of Étrangeté Op.63.

No. 1 Allegretto

No. 2 Allegretto

Vers la

flamme Op. 72 (1914)

Kuldeep Jadeja

Now we

approach a work that has fascinated me nearly all my life. One can apply the

associations created by that incandescent and fiery simple melody, wrought in

small steps within the work, to any growing, personal psychic torment. The

claws of destiny appear to be incontrovertibly dragging one to

destruction. Vers la flamme Op. 72 (1914) was written on the

verge of war, accurately predicting the conflagration that was to come, a

catastrophe from which we have never recovered. According to the

pianist Vladimir Horowitz, the piece was inspired by Scriabin's prescient

conviction that a constant accumulation of heat would ultimately cause the

destruction of the earth (an early vision of 'global warming'?). The title

reflects the fiery destruction of the planet through a constant and

irresistible, scarcely bearable, emotional crescendo that leads, like a moth

fascinated to destruction, 'toward the flame'.

Alexeev gave us a highly emotional account of many extra-musical associations. However, I missed the metaphysical dimension of the work. The tremendously physical virtuosic pianism tended to cloud that atmosphere of desperate attraction, that sometimes unavoidable catastrophe that psychically possesses in human life, that irresistible magnetic attraction towards consciously inescapable, disaster. His crescendo could have been more of a disciplined arc leading to the final ecstatic conflagration. If the crescendo begins too early in the arc there is nowhere to go once a climax is reached. The irresistible sense of being gradually drawn like a moth into the murderous flame is lost or at least reduced. For me the work is deeply metaphysical and psychic and requires little external help to convey its sobering existential message.

As encores the Scriabin Mazurka in E Minor Op.20. This was followed by the rousing, highly melodic and rhythmic Liszt transcription of two Polish songs by Chopin, the Ring and the fully inebriated Drinking Song

21:00

August 27 Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Chamber

concert

Szymon Nehring piano

Ryszard Groblewski viola

Marcin Zdunik cello

Sonata in G minor for piano and cello Op. 65 (1846-7)

This was a fine performance of a favourite chamber work of mine, dedicated to the great French composer and cellist, friend of Chopin, Auguste Franchomme. Chopin worked terribly exhaustingly and indecisively on the G minor Sonata during the autumn of 1846 at Nohant. It forms a part of his so-called 'late style' of post-Romanticism.

The Allegro

moderato had a noble maestoso beginning quite ardent in setting the

mood. A good instrumental balance was immediately obvious, not so easy when a

modern Steinway is conjoined with the rich timbre of a 150 year old cello. At

times I felt their dialogue could have been more intimate in the counterpoint,

but the phrases were broad and emotionally embracing with carefully controlled

tensions and relaxations within the emotive moods. The cello of that excellent

musician Marcin Zdunik was so thoughtful and yearning in the suggestive

harmonic transitions Chopin offers us. Szymon Nehring showed sensitive and

subtle variation in tone and nuance.

The Scherzo could perhaps have been lighter but the cello cantabile was most expressive yet not over-sentimentalized. The Largo is such an ardent love song. Yes, I too was reminded of the Adagietto from Mahler's Fifth Symphony. I felt they could have indulged their overtly romantic, nostalgic, sentimental side a little more in imagination, but was moved by the divine melody as I always have been. The remarkable rondo Finale. Allegro was full of the joy of dance and it was clear Nehring enjoyed himself immensely in this energetic tarantella movement - as did we all! An expressive performance with a coda that was perfectly judged both in mood and musically.

Grand Duo Concertant in E major on themes from Meyerbeer’s opera ‘Robert le diable’ Dbop. 16A (1832-33)

The co-operation of the great French cellist and composer Auguste Franchomme with his friend Chopin, produced a highly entertaining, style brillant Parisian confection, that makes no excessive demands on the ear or 'dark night of the soul'. Three themes are taken from the music of Robert le diable, presented, then paraphrased.This is a tuneful and effective collaboration that pleasurably arouses all the memories of this rarely staged opera. The challenging cello part with its carefree piano 'friendship' was a delight from beginning to end. Joy at the conclusion as the sparks flew in a triumph of happiness. The Grand Duo Concertant was dedicated to a sixteen-year-old young lady, Miss Adèle Forest. She was the daughter of an amateur cellist friend of Franchomme’s and a pupil of Chopin.

Trio in G minor, Op. 8 (first performance in version with viola) (1829)

The eminent Polish

pedagogue Tomaszewski writes of this substantial work: 'For Chopin, the Trio in G minor turned into a task, a challenge and

an adventure all in one.' In this early chamber piece of Chopin, the opening Allegro con fuoco with

the rich mahogany timbre of the unaccustomed combination of viola and cello was

luxuriously and sensually attractive. The influence of Beethoven on the

composition of this movement was made clear. I felt the pastel chalk Schubertian

atmosphere which develops was more pronounced with the viola substituting for the

violin. A good balance was maintained between the instruments which is not always

so easy to facilitate. Perhaps the phrasing could have been rather more

expressive, but it such a delightful work bringing the big guns of intellectual

criticism to bear on it is simply not appropriate. Simply enjoy the lightweight

dancing of the bubbly Scherzo - Vivace although more personal interaction

between the players would have been welcome in this dance influenced movement.

The Adagio. Sostenuto has such an affecting unsentimental melody and a beautiful

cantabile was brought to the performance. It speaks so representatively

of the charming, sensitive refinement and sensibility of the composer but also

that historical age in Warsaw.

Panorama of Warsaw from Praga Bernado Belotto (1721-1780) known erroneously as his cousin 'Canaletto'

The rondo Finale. Allegretto opens with affecting innocence and later is filled with exuberant krakowiak rhythms. Tomaszewski further observes: 'The only problem is that the Trio was written in a style that is rather un-Chopin. Or perhaps it would be more appropriate to say: a style that is different to what we tend to associate with Chopin.' Even Schumann, always a enthusiast for the compositions of Chopin, rhetorically commented of this great piece of Polish chamber music: ‘Is it not as noble as one could possibly imagine? Dreamier than any poet has ever sung?’

A pleasant, charming evening of undemanding but mood elevating music, alluringly performed, so welcome in a time of frightful social depression and reversal beyond human control.

21:00 August 26 Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Piano

recital

Ingolf Wunder piano

During the 10th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition I wrote the following about the highly popular and engaging pianist Ingolf Wunder:

I

had been waiting for this Waltz for five years and it did not disappoint -

the A flat major op. 34 No.1. A great 'summons to the dance floor' and

tremendous élan in the salon with much boundless joy and contrasts

of piano and forte. I kept thinking of my

night at the Opernball in Vienna many years ago. No doubt

Chopin was calling up his own remembrances of distant balls.

Wunder

elevated this waltz into a major musical work of grand conception. Wonderful

Wunder! Of course being Austrian, it would be rather difficult as a musician to

avoid a life involving much dancing. I felt it was in his blood

and he truly understood the Mazurkas Op.24. Playing with great joy,

dancing with his body,thoughtful rubato and nostalgic cantabile. Of

course he is studying under the inspiration of that great Chopin pianist

Adam Harasiewicz which must help but he remains his own man. The Andante

spianato was beautifully considered and 'sung' in a particularly

emotional rendition with superb tone. A fine opening fanfare to the Grand

Polonaise which I felt he could see assembling on the dance

floor in his mind's eye. Enlivening dynamic contrasts with a very stylish

delivery alongside great verve and panache. Definitely Stage III and

beyond.

I am afraid

on this occasion, ten years on, I was not so pleasantly surprised. The works

chosen for this programme should have made me aware of the declamatory direction

it was going to take.

Piano Sonata in F minor

(‘Appassionata’) Op. 57

This was a performance of virtuoso tempi with dynamic

contrasts that indicated an 'heroic' conception of the work. Yes, Beethoven was

fond of sudden dynamic contrasts, but many were rather too excessive to my

mind. He also did not like the misleading nickname 'Appassionata' given

the work by the publisher. I felt the tragic nature of this work, evident in

the very opening pages, was strangely absent. The fatalistic silences within

the opening phrases could have been more eloquent. The emotional turbulence in

the Beethoven autograph must be seen by pianists, but not exaggerated with

harsh forte and dynamic inflation. I felt Wunder perhaps took

the title rather too literally concerning sensual human passions. I did not

feel sufficient philosophical exploration and refection on the nature of tragic

human destiny that so obsessed this composer. Dynamic inflation and

acceleration of tempi does not necessarily indicate despair.

What was Wunder trying to tell us concerning this

work? The chorale-like theme of the Andante con moto was a

pleasant contrast but could have been more expressive and sensitively

approached. The tempo of the final movement Allegro ma non troppo was

only partly observed - Beethoven was actually very insistent on this tempo

indication. Wunder's tone and touch, taken over by passion, was at times verged

on the brutal, particularly in the left hand. Owing to the tempo of the

movement that he adopted, the Presto coda was forced to become

a blur of sound with little or no articulation.

Overall and despite the virtuoso and extrovert panache

with which the work was performed, I felt it not to be particularly

Beethovenian, in the classical style or possessed sufficient serious meaning.

An atmospheric, theatrical and superficially exciting interpretation certainly

but not a profound one. I have never considered it to be a display piece but

the enthusiasm of the audience clearly indicated that this is an approach

fitting the 2020 gestalt.

Nocturne in E flat

major Op. 55 No. 2

Nocturne in E flat

major

I was hoping for more

sensitivity, grace, finesse and refinement in these Chopin Nocturnes, knowing

his past competition performances in 2005 and 2010, but it was not to be for

me. Some moments of subtle and loving cantabile tone and

poetry suffused the E-flat major Op.9 No.2.

Polonaise in A flat

major Op. 53

A particularly unfortunate

rendition of this majestic and dignified work, reduced rather to a virtuoso display

piece than a magisterial expression of the complex Polish emotion

of żal and a valiant but maestoso resistance to

oppression. The many solecisms complicated the effect. Similar

reflections to those above followed on the wildly enthusiastic audience response. Who am I to argue?

Mephisto Waltz No. 1, S. 514 (Der Tanz in Der Dorfschenke – The Dance in the Village

Inn).

Liszt was obsessed

by Faust and he chose the account of the story by Nikolaus Lenau to set this

piece of programme music. This passage from Lenau appears in the actual score:

There is a wedding feast in progress in the village inn, with music, dancing,

and drunken carousing. Mephistopheles and Faust wander by, and Mephistopheles

persuades Faust to enter and join in the festivities. Mephistopheles grabs the

violin from the hands of a sleepy violinist and draws from the instrument

seductive and erotically intoxicating strains. The amorous Faust whirls about

with a sensual village beauty [the landlord's daughter] in a wild dance;

they waltz in mad abandon out of the room, into the open, away into the woods. The sounds

of the violin grow softer and softer, and the nightingale sings his

love-soaked song.

Wunder gave us a commanding, rather over-excited, perhaps forgivable, sensationalist keyboard account of this work. There were many solecisms. The passionate, insidiousness of the creepy seductive Mephistopheles, his misleading, 'loving' erotic gestures, the expressive literary theatre Liszt attempted to create in music, was submerged by dynamic and tempo exaggeration. What was Wunder trying to tell us about the characters of Mephistopheles, Faust and Gretchen?

Liszt was deeply concerned with literature as were many nineteenth century composers. The influence of Lord Byron on the Romantic sensibility of Europe, his scandalous life and magnificent narrative poetry cannot be underestimated. Liszt tempts pianists fearfully to extremes through his formidably crowd-gathering, impressive keyboard pyrotechnics. He is greatly in need of rehabilitation from a rather limited, virtuosic view of his complex, referential artistic, religious and musical mind and musical imagination.

Piano Sonata in B minor S. 178

The manner in which a pianist opens this masterpiece tells you

everything about the conception that will evolve. The haunted repeated notes produced

were of the right duration (a terrible battle lies in wait for pianists here -

Krystian Zimerman drove his recording engineers mad repeating it hundreds of

times before being satisfied). Just to have this vast work in your fingers is a

massive achievement but what you do with this is another matter

altogether, what you have to say about this work.

This famous

Sonata was published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1854 and first performed

on January 27, 1857 in Berlin by Hans von Bülow. It was attacked by

the German Bohemian music critic Eduard Hanslick who said rather colourfully ‘anyone

who has heard it and finds it beautiful is beyond help’. Among the many divergent

theories of the meaning of this masterpiece we find that:

- The Sonata is a musical portrait of the

Faust legend, with “Faust,” “Gretchen,” and “Mephistopheles” themes

symbolizing the main characters. (Ott, 1981; Whitelaw, 2017)

- The Sonata is autobiographical; its

musical contrasts spring from the conflicts within Liszt’s own

personality. (Raabe, 1931)

- The Sonata is about the divine and the

diabolical; it is based on the Bible and on John Milton’s Paradise

Lost (Szász, 1984)

- The Sonata is an allegory set in the

Garden of Eden; it deals with the Fall of Man and contains “God,”

“Lucifer,” “Serpent,” “Adam,” and “Eve” themes. (Merrick, 1987)

- The Sonata has no programmatic allusions;

it is a piece of “expressive form” with no meaning beyond itself. (Winklhofer,

1980)

This is a profound piece, too often played as some type of hectic piano fantasy or dream fantasy when it is actually in many respects a philosophical dialogue between different fundamental aspects of the human spirit as possibly symbolized by Faust, Mephistopheles and Gretchen. Liszt was tremendously influenced by literature and poetry in his compositions and in particular Goethe’s Faust, the dramatic spiritual battle between Faust and Mephistopheles with Gretchen hovering about as a seductive, lyrical feminine interlude. And it is a far more complex musical and structural argument than that this rather trite account of mine would indicate. Wunder did not always communicate these complex possibilities.

Eugène Delacroix - a rare illustration to Goethe's Faust

In many ways this sonata is an opera of life and in fact has a rather semi-programmatic narrative, not unlike Liszt's own life or a Byronic poem. Remember the programme of his Symphonic Poems, a form he invented as a composer. One must also remember not to overlook the deep religious dimension to Franz Liszt, all too easy in our largely secular Western world. There was a belief that serious transgressions would actually take you to a real place called Hell. There is a feeling of evil and the smell of the sulphurous inferno in this sonata which could have been communicated more strongly. It is replete with almost every human emotion from birth to death, even unto celestial redemption at the conclusion.

Lithograph by Eugène Delacroix - Faust and Mephistopheles Galloping Through the Night

One must perceive

the extra-musical dimensions in Liszt and not dismiss them as merely cosmetic to

interpretation and therefore dispensable. A deep interpretation requires understanding

not only of his complex psyche (at best we can only partially enter the mind of

the Other) but the cultural, historical and social priorities of his

revolutionary period. There is extensive, expressive and philosophical poetry

in Liszt, but today's musical culture has almost submerged it by temptation to

pianistic ostentation.

One only has to read accounts of his playing by his students in Weimar to realize how far we have strayed from the original source and embraced the attractive legend of modern celebrity cultural nuances. An unanticipated shock that his playing sometimes 'sounds like filigree lace' springs to mind, this from his eminent pupil in Weimar, the pianist and conductor, Hans von Bulow. Surely one should feel at the conclusion of such a masterpiece ‘What incredible music this is!' rather than 'What an incredible performer this is!' although that can be justified. At the conclusion there should be nothing left to say ...

As an encore Wunder performed an attractive virtuosic piece of his own composition entitled Liberty

17:00 August 26 Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Piano

recital

Kamil Pacholec piano

This was the same programme Pocholec presented at the Duszniki Zdrój International Chopin Festival on the afternoon of August 11 but with the addition of the Paderewski Cracovienne fantastique in B major Op. 14 No. 6. This is my somewhat modified review of that concert; his approach was similar but I will add observations and highlight significant differences in interpretation that I noticed. It was said Chopin never played the same work in same way twice, allowing spontaneity full flight.

During the 11th International Paderewski Piano Competition in Bydgoszcz in November 2019, where Pacholec was awarded Second Prize, he performed the Mozart Concerto No. 21 in C major, K. 467. For this performance he was awarded a Special Prize for the best performance of a Mozart piano concerto. I wrote on that occasion: There was affecting good humor in the Allegro maestoso with variations in tempi which made it most expressive. Tone, articulation and touch possessed great finesse. The cadenza was graceful and refined as well as inventive.

This affinity with Mozart showed itself in the elegant, refined expressiveness and improvisatory fantasy of his presentation of the Fantasia in D minor K. 397 (1782).

In the Paderewski Competition mentioned above, he was also given the Paderewski Music Society of Los Angeles opportunity to give a piano recital in the Paderewski Music Society Recital Series in the artistic season 2020/2021. He also was awarded the Paderewski Pomeranian Philharmonic in Bydgoszcz Prize for the best performance of Paderewski for a Finalist in the Competition. I also was particularly fond of his interpretations where he showed at the time that he had a far more idiomatic feeling for this music than most of the other contestants.

In

the Paderewski Miscellanea. Sèrie de moreceaux Op. 16

No. 3 Thème varié in A major (1885–87) he displayed the

perfect Paderewskian sentiment.

You know,

Paderewski is such an underestimated composer of affecting lyrical and poetic

piano music which speaks directly to the heart and sensibility, rather than

burdening the intellect with high seriousness.

Naturally,

being a great patriot he writes many Polish mazurkas and polonaises but much of

his solo piano music reminds me of a superb film score for say

an intensely romantic French love affair set in Provence directed by

say Francois Truffaut. In our imaginations we could be

bowling along a poplar lined route secondaire past

hills of vineyards with Catherine Deneuve or Stephane Audran in the passenger

seat of a Chapron Citroen DS 3 cabriolet. Her hair is wonderfully awry in the

wind as we head towards une belle gentilhommiere and

nights of sophisticated sensual bliss, days of cultivated tastes, food and

wine. Ah…what we have lost of true civilization and culture in 2020…and

now this ghastly pandemic ..... Paderewski had all the greatness that

civilization could offer and then came the Great War.

The music

of Paderewski wears its learning lightly with poetry, charm, elegance