75th Duszniki Zdrój International Chopin Festival. 7-15 August 2020

| |

|

SATURDAY, 15 AUGUST CHOPIN MANOR

8:00 pm

FINAL PIANO RECITAL

KEVIN KENNER

Ned Rorem

(b.1923)

Kevin Kenner

began his recital with a composition by an American composer little known in

Poland or to me. Ned Rorem studied at Northwestern University and at the Curtis

Institute in Philadelphia, later serving as secretary and copyist to Virgil Thomson

and completing his musical studies at the Juilliard Institute. He spent 1949 to

1958 in France and came to know all the cultural luminaries of the day,

befriending many of them. He returned the US and held various academic

positions, teaching at the Curtis Institute from 1980. He was also an excellent

writer of straightforward, sometimes shocking opinions. His notoriously

intimate Paris Diary published in 1966 caused a significant degree of

scandal concerning sexual orientation.

Ned Rorem at 95 (New York Times)

Rorem was a

composer of vocal music - some 400 songs - settings of Robert Frost, Gerard

Manley Hopkins, Edith Sitwell, Roethke, O’Hara, Carlos Williams, Auden,

Whitman, Cocteau, Gide and Colette. His operatic works range from A

Childhood Miracle (based on Nathaniel Hawthorne) to Miss

Julie (after Strindberg) and Three Sisters Who are Not

Sisters (with a text by Gertrude Stein). He also wrote orchestral

works (three symphonies and concertos) in addition to piano and chamber works.

Kenner chose

his Barcarolle No. 2 (1949). This is a rather charming, mellifluous

piece written in conventional diatonic harmony. He wrote many articles in

opposition to the contemporary musical avant-garde of say Pierre Boulez,

Luciano Berio and Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Robert

Schumann

Kenner then rather seamlessly moved onto the Romance in F sharp major Op. 28 No. 2 (1839) of Robert Schumann. Perhaps he designed the programme to reflect

Rorem's love of Schumann.

In 1839 , Clara Wieck received Three Romances Op 28 from her fiancé as a Christmas gift. Robert did not consider them to be ‘good or worthy enough’ to be dedicated to her. In opposition to this judgement, Clara wrote to him on 1st January 1840 ‘… as your bride, you must indeed dedicate something further to me, and I know of nothing more tender than these 3 Romances, in particular the middle one, which is the most beautiful love duet.' Clara suggested that he revise them before publication in October 1840. Schumann later believed the Romances to be among his most successful works. The marriage however was never to be the ideal romantic marriage as conventionally depicted. There were to be many marital tensions and resentments between these two creatively different personalities.

The Romance No. 2 (Einfach), which translates from German as 'simply' or 'plainly' . This character is reflected by a straightforward melody with simple harmonies and restricted harmonic range. This piece, with its memorable cantabile melody, became rather popular. Kenner brought sensitivity, love and lyricism to his beautifully nuanced interpretation.

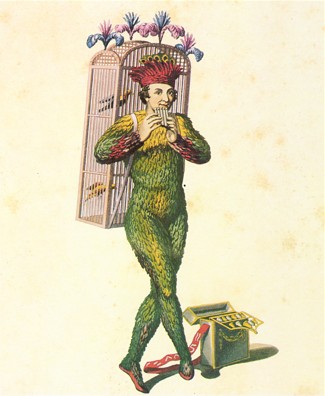

He then performed the remarkable masterpiece Davidsbündlertänze (Dances of the League of David), Op. 6 (1837). This is a set of 18 pieces and one of the great works of Western Romantic piano literature. The Davidsbündler (League of David) was a music society founded by Schumann in his literary musings. The League itself was inspired by real or imagined literary societies such as those created by E.T.A Hoffmann. The major theme was based on a mazurka by Clara Wieck and was inspired by his love of her and hope for their union ('many wedding thoughts') which permeates all the works of this period. Her presence is rather subliminal throughout the whole cycle.

Literature and music had a

symbiotic relationship for Schumann and was a source of the unique qualities of

his genius. He was famous at this time as a perceptive music critic, even over

knowledge of him as a composer. He considered music criticism, extra-musical

criticism, to be an art form. In this

work it is clear he was gaining in musical self-confidence as a composer with

his increasing attraction to the public. The masks of Carnaval are

stripped away and the poet's face here revealed.

The pieces are not really dances but musical 'dialogues' concerning contemporary music that take place between Florestan (rasch - quick or hasty) and Eusebius (innig - intimate). Schumann created these characters to represent the active and passive aspects of his personality. The enigmatic description of No.9 reads 'Here Florestan stopped, and his lips trembled sorrowfully.' I cannot analyse here each of the eighteen movements of the work, although I would dearly love to do this. Save to say, Kenner gave a marvellously energetic, electrical performance of Florestan, together with the other side of the human coin, the tender cantabile that depicted the gentle lyricism of Eusibius. En passant he captured so much of the poetic, mercurial, impetuous, whimsical and lyrical aspects of Schumann's nature. He carefully preserved the unity of this cycle that allows us to experience ‘music as landscape’ (Charles Rosen).

Intermission

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849)

Young Chopin

Kevin Kenner

planned the second half of his programme to emphasis the extraordinary achievements

of the young Chopin and how the seeds of his future development were planted

and began to bud. This is joyful music, a delight of youthful energy and genius,

as yet unclouded by the tigers of experience.

Nocturne

in E minor Op. 72 No. 1 (1827)

There is some debate concerning the chronology of this nocturne as it shows many of the hallmarks of maturity despite its early date. Zdzisław Jachimecki (1882 –1953), the Polish music historian, composer and professor, thought the piece reflected the 'melancholic state of the soul'. I have always loved the simplicity of this Nocturne, its sense of bleak longing and aspects of rather hopeless aspiration. It was published by Julius Fontana after Chopin's death. Kenner played it with sensitivity, sensibility and understanding of the psyche of this complex composer. I might have wished it even more 'disembodied', like a wraith of passing regret, scarcely material. Perhaps though as a young man, Chopin could not have imagined such a conception with the rarefied poetry of bitter experience at its core.

Mazurkas Op. 7 (1830–31)

No. 2 in A minor

No. 1 in B flat major

Mazurka in C sharp minor Op. 6 No. 2 (1830–31)

Mazurka in D major Op. 33 No. 3 (1837–38)

Mazurka in C major Op. 6 No. 5 (1830-31)

The mazurka is the quintessential expression of the Polish national and ethnic identity. Any approach to them is bound to cause comment, sometimes dismissive, sometimes abrasive but never indifferent or detached.

Interestingly I think Kenner played the original version of this mazurka found in the album of his teacher Elsner's daughter Emilia. He played the introductory ritornel in the key of A major, taken from the music of a village band, and defined by Chopin with the word Duda. He concluded with the same phrase. A fascinating idea, played in quite a different mood to what we are accustomed to with this mazurka with much spontaneous improvisation. May displease the purists but it started me thinking...

To understand what I think Kenner was attempting in this group of mazurkas (I am not sure mind you - just an hypothesis!), one has to examine the nature of dancing in Warsaw during the time of Chopin. Almost half of his music is actually dance music of one sort or another and a large proportion of the rest of his compositions contain dances.

Dancing was a passion especially during carnival from Epiphany to Ash Wednesday. It was an opulent time, generating a great deal of commercial business, no less than in Vienna or Paris. Dancing - waltzes, polonaises, mazurkas - were a vital part of Warsaw social life, closely woven into the fabric of the city. There was veritable 'Mazurka Fever' in Europe and Russia at this time. The dancers were not restricted to noble families - the intelligentsia and bourgeoisie also took part in the passion.

Chopin's experience of dance, as a refined gentleman of exquisite manners, would have been predominantly urban ballroom dancing with some experience of peasant hijinks during his summer holidays in Żelazowa Wola, Szafania and elsewhere. Poland was mainly an agricultural society in the early nineteenth century. At this time Warsaw was an extraordinary melange of cultures. Magnificent magnate palaces shared muddy unpaved streets with dilapidated townhouses, szlachta farms, filthy hovels and teeming markets. By 1812 the Napoleonic campaigns had financially crippled the Duchy of Warsaw. Chopin spent his formative years during this turbulent political period and the family often escaped the capital to the refuge of the Mazovian countryside at Żelazowa Wola. Here the fields are alive with birdsong, butterflies and wildflowers. On summer nights the piano was placed in the garden and Chopin would improvise eloquent melodies that floated through the orchards and across the river to the listening villagers gathered beyond.

Of course he was a perfect mimic, actor, practical joker and enthusiastic dancer as a young man, tremendously high-spirited. He once wrote a verse describing how he spent a wild night, half of which was dancing and the other half playing pranks and dances on the piano for his friends. They had great fun! One of his friends took to the floor pretending to be a sheep! On one occasion he even sprained his ankle he was dancing so vigorously! He would play with gusto and 'start thundering out mazurkas, waltzes and polkas'. When tired and wanting to dance, he would pass the piano over to 'a humbler replacement'. Is it surprising his teacher Józef Elzner and his doctors advised a period of 'rehab' at Duszniki Zdrój to preserve his health which had already begun to show the first signs of failing? This advice may not have been the best for him, his sister Emilia and Ludwika Skarbek, as reinfection was always a strong possibility there. Both were dead not long after their return form the 'cure'.

Many of his mazurkas would have come to life on the dance floor as improvisations. Perhaps only later were they committed to the more permanent art form on paper under the influence and advice of the Polish folklorist and composer Oskar Kolberg. Chopin floated between popular and art music quite effortlessly.

By running the mazurkas together attacca,

changing the rhythm slightly, adopting variants and introducing spontaneous

improvised embellishments, Kenner engaged us in the sheer fun and unruly exuberance

of Chopin as a vibrant, musically improvising young pianist. After all he was a

master of this domain of performance and the mazurka is particularly

predisposed to improvisation. This Kenner imaginatively did rather than

interpreting these early mazurkas with the 'holy concentration' of the Urtext. I

really have no idea if I am on the right track here, pure conjecture, but found the approach lively, fresh,

unique, instructive and entertaining. This speculation is merely my

'halfpennyworth'. George Sand wrote in Les Maîtres Sonneurs (The Master

Pipers) 'He gave us the finest dances in the world....so attractive and easy

to dance to that we seemed to fly through the air.'

Rondo à la Mazur in F major Op. 5 (1825–26)

Written when Chopin was 16. He dedicated

it to the Countess Alexandrine de Moriolles, the daughter of the Comte de

Moriolles, who was the tutor to the adopted son of the Grand Duke Constantine,

Governor of Warsaw. The rather unpleasant individual often requested Chopin to

play for him at the Belvedere Palace. Unable to sleep, on winter nights he would

ostentatiously send a sleigh drawn by four-horses harnessed abreast in the Russian style to collect

the young pianist from his home. Schumann first heard the Rondo à la mazur in

1836, and he called it 'lovely, enthusiastic and full of grace. He who does

not yet know Chopin had best begin the acquaintance with this piece'.

Kenner gave a truly uplifting joyful, unbuttoned, style

brilliant interpretation of this work, so therapeutic during this ghastly

pandemic which has leached so much carefree pleasure from our lives. The articulation

and sense of dance was also infectious, but in the very best way!

Polonaise

in D minor Op. 71 No. 1

(1824–27)

The early

polonaises of Chopin are unjustly neglected. He was only around 15 when he

composed this one. I found the mood rather playful which seemed to indicate Kenner's

mood on this occasion!

Variations

in B flat major on 'Là ci darem la mano' from Mozart’s Don Giovanni Op. 2 (1827–28)

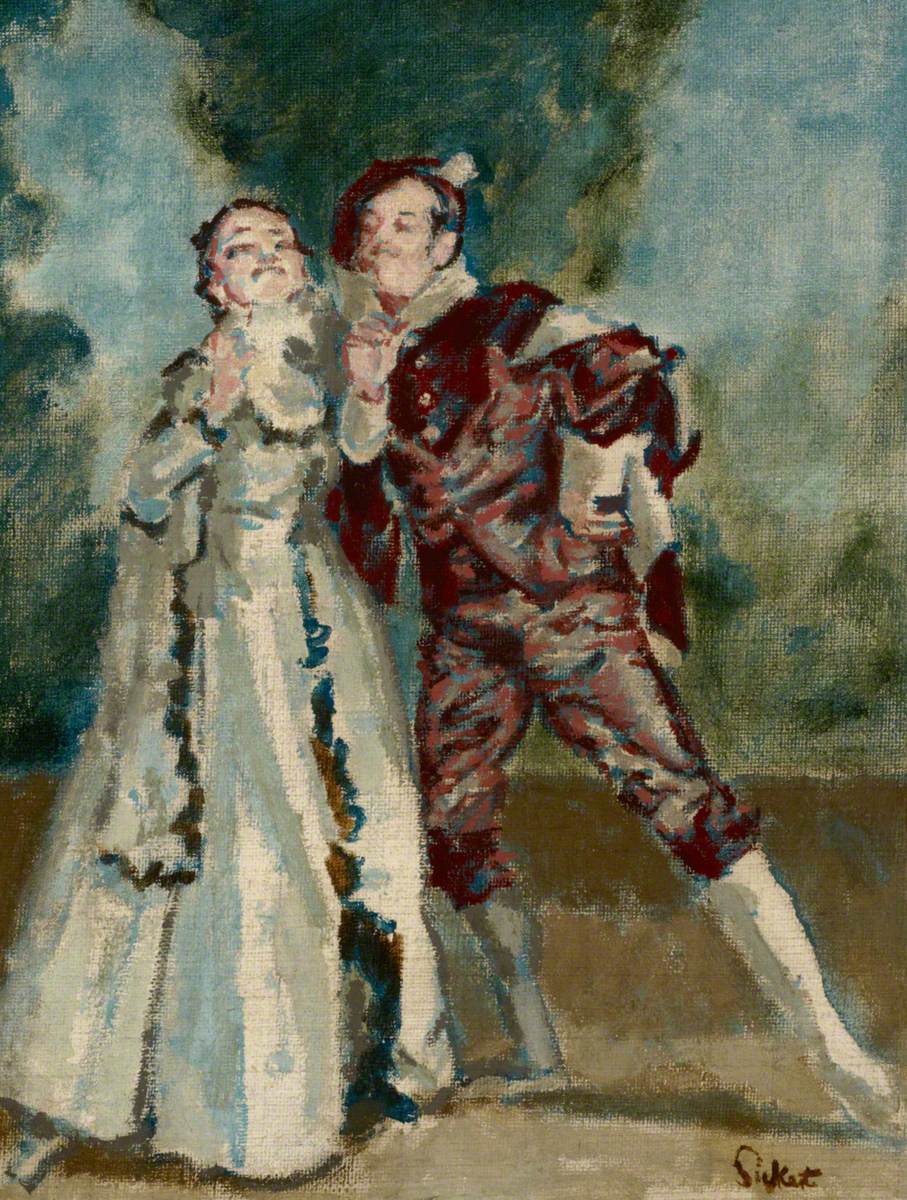

'Là ci darem la mano' Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942) (National Trust, Fenton House)

Chopin

composed the ‘Là ci darem’ Variations in 1827. As a student of the

Main School of Music, he had received from Elsner another

compositional task: to write a set of variations for piano with orchestral

accompaniment. As his theme, he chose the famous duet between Zerlina and Don

Giovanni from the first act of Mozart’s opera Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni. In this opera overwhelming

power and faultless seduction meet maidenly naivety and barely controlled

fascination. (Tomaszewski)

In his famous

first review of Chopin's variations on Mozart’s 'Là ci darem la mano',

Schumann gives us a striking description:

“Eusebius

quietly opened the door the other day. You know the ironic smile on his pale

face, with which he invites attention. I was sitting at the piano with

Florestan. As you know, he is one of those rare musical personalities who seem

to anticipate everything that is new, extraordinary, and meant for the future.

But today he was in for a surprise. Eusebius showed us a piece of music and

exclaimed: ‘Hats off, gentlemen, a genius! Eusebius

laid a piece of music on the piano rack. […] Chopin – I have never heard the

name – who can he be? […] every measure betrays his genius!’”

Chopin’s ‘Là

ci darem’ variations are classical in form with an introduction,

theme, five variations and finale. They are a marvellous example of the style

brillant and clearly influenced by Hummel and Moscheles. Kenner observed the correctly indicated and deliberate tempo Largo that opens the work without the

over-declamatory energy many pianists adopt. It is well-known Chopin was

obsessed with opera all his life, a fascination that began early.

The first statement

of 'Là ci darem la mano' was

genuinely expressive of the mood of the opera but perhaps slightly lacking in an

undertone of beguiling seduction. Kenner

brought an effortless style brillant introduction to this

fiendishly difficult work followed by developments that were light, elegant and

stylish. Each variation was carefully delineated in

character and had the feeling of carefree and enjoyable improvisation. The songlines had a winning cantabile with

the right jaunty rhythm.

Clara Wieck

loved this work and performed it often making it popular in Germany. Her

notorious father, who had forbidden her marriage to Robert Schumann,

wrote perceptively and rather ironically of this work: ‘In his

Variations, Chopin brought out all the wildness and impertinence of the Don’s

life and deeds, filled with danger and amorous adventures. And he did so in the

most bold and brilliant way’.

Kenner brought a definite feeling

of the late 18th century to its style and artfulness. He approached the work rather

in the spirit of a virtuoso display piece, clearly enjoying himself

immensely, which was surely Chopin's intention. Waterfalls of glittering

notes cascaded around us as in the original descriptions of jeu

perlé.

And so came to a conclusion a carefully planned experience of the carefree youth of Fryderyk Chopin. This before the suffering of exile, chronic ill-health and the travails of love took hold of his body, heart and soul.

A standing ovation from the Duszniki audience, the sole encore being the beautiful simplicity of the Chopin song Wiosna (Spring).

SATURDAY 15

AUGUST CHOPIN MANOR 4:00 pm

PIANO RECITAL

ANDRZEJ

WIERCIŃSKI

Winner of many Polish Chopin National and International Prizes including the Gold Medal at the 1st International Music Competition in Vienna. Last year he won the Silver Medal at the International Music Competition in Berlin.

Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) – Chaconne

from Partita No. 2 in D minor for solo Violin BWV 1004 (1720)/Ferruccio

Busoni (1866-1924)

He began his

recital with this work.

It is a

well known fact that in his writing for the pianoforte Busoni shows an

inexhaustible resource of color effect.... This preoccupation with color

effects on the pianoforte began to make itself evident after Busoni had began

to devote himself to the serious study of Liszt, but it remained to dominate

his mind up to the end of his life.

[Edward J. Dent, Ferruccio Busoni. A biography

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966), pp. 145-146]

I have always

liked this work transcribed by Busoni 1891-2. Bach occupied and inspired the

composer for his entire life. 'Bach is the foundation of pianoforte

playing,' he wrote, 'Liszt the summit. The two make Beethoven

possible.' It is not surprising then that the grandeur, invention and

monumentality of the Chaconne from this Partita attracted

his imaginative mind. Bach himself, he notes, was a prolific arranger of his

own music and that of other composers.

'Notation

is itself the transcription of an abstract idea. The moment the pen takes

possession of it the thought loses its original form.'

Bach had

composed it after learning in 1720 of the death of his beloved wife Maria

Barbara, the mother of his first seven children. Bach had been in Karlsbad with

his patron, the highly musical Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. When Bach

returned to Cöthen after three months he discovered his young wife of 35, who

was in excellent health when he departed, had died during his absence and even

worse, been buried. His grief-stricken response resulted in this composition

for violin full of pain, suffering and melancholic nostalgia, even anger, at

the indiscriminate nature of destiny.

Wierciński began the work with arresting clarity and transparency at a tempo that gave it nobility of utterance. He is in command of a virtuoso piano technique. However, as it progressed I felt that many opportunities for deeper expressiveness were missed. A great shame as his dominance of the work digitally was total. The phrasing did not breathe sufficiently to give air, dynamic variety and colour to relieve the headlong tempo. Virtuosity tempted him as it might any pianist but one must not forget Busoni was as concerned with degrees of expressiveness as any Romantic composer.

I felt at times Wierciński

overplayed the twenty-nine variations of the work without enough variety. The

polyphony was impressive but a degree of over-pedalling lessened the subtle

colours within the soundscape. The melodic lines and the weight and

significance of chords, although stirring and exciting in their abandonment,

tended to be dynamically overwrought. I feel Wierciński was genuinely

attempting to create a magnificent seventeenth century Thuringian organ and its

16' stop but with limited success. He gave the work a noble and triumphal

conclusion. Overall a very satisfying performance of a piece that

makes immense demands on a pianist and requires time to properly mature in the

mind to adequately rise to its musical challenges.

Although perhaps

grossly unfair to this young man, I have the temerity to recommend listening to

the recording of Mikhail Pletnev live at Carnegie Hall in November 2000.

Another possibly unfair suggestion, is the performance given by Arturo

Benedetti Michelangeli given in Warsaw in March 1955. Not to imitate of course

but to fertilize further musical thought.

A rare picture of Ferrucio Busoni playing a pedal harpsichord with a 16' stop, possibly an inspiration for his Bach organ transcriptions that naturally were transformed into something highly pianistic.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849)

Nocturne in B flat major Op. 62 No. 1 (1846)

A Tuberose at night

Interestingly

in the Anglo-Saxon world, the B major Nocturne has been

given the name of an exotic greenhouse flower: ‘Tuberose’. The American

art, book, music, and theatre critic James Huneker explains why: ‘the

chief tune has charm, a fruity charm’, and its return in the reprise ‘is faint

with a sick, rich odor’. Wierciński

performed this work with the sensitivity it deserves and created quite an

hypnotic atmosphere. There is great variety in the mood and writing of this

rather untypical Chopin nocturne. I felt occasionally his phrasing verged on

the mannered but this is always difficult to judge accurately in works that

rely on deep emotive expression.

Ballade in

F minor Op. 52 (1842–43)

Penetrating the expressive core of the Chopin Ballades requires an understanding of the influence of a generalized view of the literary, musical and operatic balladic genres of the time. In the structure there are parallels with sonata form but Chopin basically invented an entirely new musical material. I have always felt it helpful to consider the Chopin Ballades as miniature operas being played out in absolute music, forever exercising one's musical imagination.

The brilliant Polish musicologist

Mieczysław Tomaszewski describes the musical landscape of this work far more

graphically than I ever could. The narration is marked, to an incomparably

higher degree than in the previous ballades, with lyrical expression and

reflectiveness [...] Its plot grows entangled, turns back and stops. As in the

tale of Odysseus, mysterious, weird and fascinating episodes appear [...] at

the climactic point in the balladic narration, it is impossible to find the

right words. This explosion of passion and emotion, expressed through

swaying passages and chords steeped in harmonic content, is unparalleled. Here,

Chopin seems to surpass even himself. This is expression of ultimate power, without a hint of emphasis or

pathos [...] For anyone who

listens intently to this music, it becomes clear that there is no question of

any anecdote, be it original or borrowed from literature. The music of this

Ballade imitates nothing, illustrates nothing. It expresses a world that is

experienced and represents a world that is possible, ideal and imagined.

Wierciński gave us a dramatic interpretation overlaid with lyricism with periods of reflection. This he managed with a warm tone, clarity and articulation that he had already indicated in the Bach. I thought he emphasized the strong narrative declamatory elements and expressive polyphony in a musically satisfying manner. The balladic tale twists and turns were most expressively delineated if slightly mannered on occasion. At one moment passionately lyrical, then introspective, then expressing that characteristic Polish bitterness, passion and emotionally-laden disturbance of the psyche known as żal. There were moments when I felt rushed by his phrasing, reluctantly taken quickly up the knotted rope of passion. What a monumental story of shifting realities is displayed in this work!

Wierciński took us on a satisfying and moving journey in this great opera of the human psyche. His ability to build dramatic tension followed by lyrical relaxation was managed with great skill. He gave us a passionate coda to the work.

Mazurkas Op.

24 (1833–35)

No. 1 in G

minor

This popular slightly

rural mazurka I found expressive with much variety and often affecting rubato. The

loss of happiness irrevocably. Occasionally with Wierciński, I feel slightly

uneasy at what one might call rather 'cultivated' sentiments.

No. 2 in C

major

Here I found

delightful contrasts of mood brought a decidedly colorful personality to this

Polish performance. Certainly I felt present in the imaginative dream of a

possibly remembered rustic dance (an oberek).

No. 3 in A

flat major

I would

describe the character Wierciński brought to this mazurka as one of 'blithe

rurality', the dance melody derived from a kujawiak.

No. 4 in B

flat minor

This

masterpiece in the mazurka genre is beloved by everyone! Many pianists through

history have had it in their repertoire.

This mazurka has even been nicknamed the ‘Rubinstein’,

as Anton Rubinstein was supremely fond of playing it. It can be considered a

'lyrical dance poem'. Here I felt Wierciński

achieved his own voice and understood the direction of the harmonies. I noticed

judicious and skillful pedaling in this mazurka which augmented his winning

tone and touch.

Scherzo in

E major Op. 54 (1842–43)

Then he performed the rarely

performed Scherzo in E major Op.54. This scherzo

is not dramatic in the demonic sense of the three previous scherzi, but lighter

in ambience. The outer sections are a strange exercise in rather joke-filled

fun with a darkly concealed centre of passionate grotesquerie. The work mysteriously

encloses a deeply felt and ardent nocturne in the form of a longing love poem, suffused

with a sense of loss. Wierciński

was able to express the complexity of these emotions with conviction, even if

slightly lost in the labyrinth at times. He delighted us with the beauty of tone

and lightness of articulation.

Playfulness with hints of

seriousness and gravity underlie the exuberant mood of this scherzo. Wierciński maintained this expressive

balance very well, only slightly missing the emotional ambiguities that run

like a vein though the work. The central section (lento, then sostenuto)

in place of the Trio, gives one the impression so often with Chopin, the

ardent, reflective nature of distant love. Wierciński was rather moving in this

beautiful cantabile. He yet brought a sense of triumph

and the will to carry on with life in the passionate last chords that close the

work.

Heinrich Heine, a German poet who idolized Chopin, asked himself in a letter from Paris: ‘What is music?’ He answered ‘It is a marvel. It has a place between thought and what is seen; it is a dim mediator between spirit and matter, allied to and differing from both; it is spirit wanting the measure of time and matter which can dispense with space.’

As an encore a powerful performance of the A-flat major Polonaise Op.53

His second encore was a moving and poignant Siloti arrangement of the Bach Prelude in B minor

His third encore was a Chopin piece I had never before heard. The attractive and delightful Introduction and Variations in B flat major On A Theme from Herold's 'Ludovic' Op.12 ('Variations Brillantes')

FRIDAY, 14 AUGUST

CHOPIN MANOR 8:00 pm

PIANO RECITAL

ALBERTO NOSÈ

This Italian

pianist was born in Verona in 1979. He has won a veritable bouquet of world

laureates. In the year 2000 Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw he

achieved fifth place, the year it was won by Yundi Li. I had heard him at

Duszniki in 2006 and 2012 from which this extract of my review is taken:

On this

occasion he chose the same Beethoven Sonata in E flat major ‘quasi una

fantasia’ Op. 27 No. 1 that he played in 2006. From the opening bars I

realized I was in the presence of a refined and accomplished artist with a

complete command of the Beethovenian aesthetic and style. Each movement felt as

if it existed alone but at the same time the movements ran together (attacca

subito) absolutely intelligibly. His touch highlighted the different

textures perfectly of each movement (legato and staccato contrasts

for example). This was a deeply satisfying performance but not perhaps as

philosophical as the deeply considered Claudio Arrau view.

He followed

this with a rather tempestuous even ‘possessed’ performance of Liszt’s Dante-Sonata.

Fantasia quasi sonata ‘Après une lecture du Dante’. His interpretation

had all the haunted passion and understanding of Dante’s Inferno and Paradiso as

a source one could wish for (the pianist is a Northern Italian after all). His

technique was awesome in this work.

Frédéric

Chopin (1810-1849)

– Polonaise in C sharp minor Op. 26 No.

1 (1835)

Such

sensitive phrasing and fine tone - full of sensibility, expression and dynamic

variation. The cantalina is one of the most beautiful Bellini -influenced

arias Chopin ever wrote, full of nostalgic longing for both personal love and his

homeland. Nosè was quite superb in this

with its flickers of żal like a Polish electrical summer storm.

– Mazurkas

Op. 56 (1843–4)

No. 1 in B

major

Beautiful

nostalgia expressed here by Nosè within its harmonically adventurous and fragmented

nature. The mazurka rhythm emerges triumphant.

No. 2 in C

major

Ferdynand Hoesick described this

mazurka that has such a rustic dance feel as follows: ‘The basses bellow,

the strings go hell for leather, the lads dance with the lasses and they all

but wreck the inn’. I felt Nosè could have been more

boisterous and rumbustious!

No. 3 in C

minor

I always felt

this mazurka as not based in reality but in nostalgic dream and memories. I

felt Nosè brought slightly too much Latin passion and reality to this fragile,

refined work which drifts over the Mazovian plain on a summer breeze fading

away to nothing as an autumn leaf falls into a stream...

– Ballade

in G minor Op. 23 (1835–36)

‘I have received

from Chopin a Ballade’, Schumann informed

his friend Heinrich Dorn in the autumn of 1836. ‘It seems to me to be the

work closest to his genius (though not the most brilliant). I told him that of

everything he has created thus far it appeals to my heart the most. After a

lengthy silence, Chopin replied with emphasis: “I am glad, because I too like

it the best, it is my dearest work”.’

Mieczysław Tomaszewski paints the background to this work best: It was during those two years that what was original, individual and distinctive in Chopin spoke through his music with great urgency and violence, expressing the composer’s inner world spontaneously and without constraint – a world of real experiences and traumas, sentimental memories and dreams, romantic notions and fancies. Life did not spare him such experiences and traumas in those years, be it in the sphere of patriotic or of intimate feelings. [...] For everyone, the ballad was an epic work, in which what had been rejected in Classical high poetry now came to the fore: a world of extraordinary, inexplicable, mysterious, fantastical and irrational events inspired by the popular imagination. In Romantic poetry, the ballad became a ‘programmatic’ genre. It was here that the real met the surreal. Mickiewicz gave his own definition: ‘The ballad is a tale spun from the incidents of everyday (that is, real) life or from chivalrous stories, animated by the strangeness of the Romantic world, sung in a melancholy tone, in a serious style, simple and natural in its expressions’. And there is no doubt that in creating the first of his piano ballades, Chopin allowed himself to be inspired by just such a vision of this highly Romantic genre. What he produced was an epic work telling of something that once occurred, ‘animated by strangeness’, suffused with a ‘melancholy tone’, couched in a serious style, expressed in a natural way, and so closer to an instrumental song than to an elaborate aria.

Nosè gave us an

impressive, virtuosic and rhapsodic account of this great work. It did emerge

as a narrative drama, but his dynamic phrasing could perhaps have been more

graduated and expressive as this emotional history of a tormented soul unfolded.

The fiery emotional passions Chopin unleashes tempt the pianist to be carried away.

– Nocturne

in C minor Op. 48 No. 1 (1841)

This

monumental, tragically majestic composition is a triumph of passion battling against

constraint. The chorale opening is desperately moving in its dark nostalgia. Nosè

began reflectively and at a considered tempo which permitted great sensibility

of nuance. He controlled the tremendous growth of sound with sensitive rubato

and oceanic waves of driven harmonies before the mighty winds subside into a

type of spiritual resignation. His contrasts of mood were deeply affecting.

– Scherzo

in B flat minor Op. 31 (1836–37)

Here we have

another great narrative drama, an eruption of dramatic force that leads almost

to its own destruction. A perfect example of 'Chopinian

dynamic romanticism'. Nosè offered

a tremendously exciting, high voltage performance of the work with irresistible

momentum and irrepressible sensuality. He was playing right on the edge of his formidable

technique, to the point where slips crept in. However, these were slips of entirely

the right kind, driven by a virtuoso pianist operating on the ragged edge of

full control, flirting with danger. Perhaps this attraction was what Michelangeli

found in driving his Ferrari at speed but not in his fiercely controlled playing.

For me this tension simply elevated the intense feeling of emotional commitment

and listener involvement brought to the work by Nosè. His lyrical and singing cantabile

Trio transported us to a dreamlike Arcadian garden from which were almost brutally

dragged away until the demolishing power of the mighty coda. Again, this was performed

by Nosè on the very edge of control. He fully deserved the enthusiastic audience

reception.

INTERMISSION

Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881)

Pictures at an

Exhibition (1874)

Modest

Mussorgsky by Victor Hartmann

This piece is

a portrait of a man walking around an art exhibition (the pictures painted by

Mussorgsky’s friend, the artist and architect Viktor Hartmann). The

composer is reminiscing on this past friendship now suddenly

and tragically cut short when the young artist

died suddenly of an aneurysm. The visitor

walks at a fairly regular pace but perhaps not always as

his mood fluctuates between grief and elated remembrance of happy times

spent together. The Russian critic Vladimir Stasov (1769-1848), to whom the

work is dedicated, commented: 'In this piece Mussorgsky depicts himself

"roving through the exhibition, now leisurely, now briskly in order to

come close to a picture that had attracted his attention, and at times sadly,

thinking of his departed friend.'

The Russian poet Arseny Goleníshchev-Kutúzov, who wrote the texts for Mussorgsky's two song cycles, wrote of its reception: There was no end to the enthusiasm shown by his devotees; but many of Mussorgsky's friends, on the other hand, and especially the comrade composers, were seriously puzzled and, listening to the 'novelty,' shook their heads in bewilderment. Naturally, Mussorgsky noticed their bewilderment and seemed to feel that he 'had gone too far.' He set the illustrations aside without even trying to publish them.

The suite of

pictures begins at the art exhibition, but the viewer and the pictures he views

dissolves at the Catacombs when the journey changes its nature. To decide on

the tempo for the Promenade is always a challenge for the

pianist. I personally wander far more slowly around art galleries or rove in my

imagination, than some pianists. The art exhibition was of Hatmann's

drawings and watercolours (not strong oil paintings) and I feel this

should be considered when approaching the dynamic range of any performance in

order to avoid undue, declamatory heaviness.

Suite of

Movements

Promenade The tempo I felt not considered enough for a

man walking elegiacally around an art gallery, wandering in scenes that flooded

his memory

The Gnome Nosè presented the gnome expressively as

rather an insidious and unpredictable character

Promenade

Sensitively performed to

match entry the following painting

The Old

Castle Nosè presented a

tender, lyrical, and reflectively nostalgic song sung by a troubadour

Promenade

Tuileries

(Children's Quarrel after Games) I

very much liked the innocence Nosè brought to this movement

Cattle Nosè was not entirely successful in

creating a picture in the mind of oxen pulling a cart or heavy, slow-moving cattle

of any kind

Promenade a thoughtful, dynamically graded transition

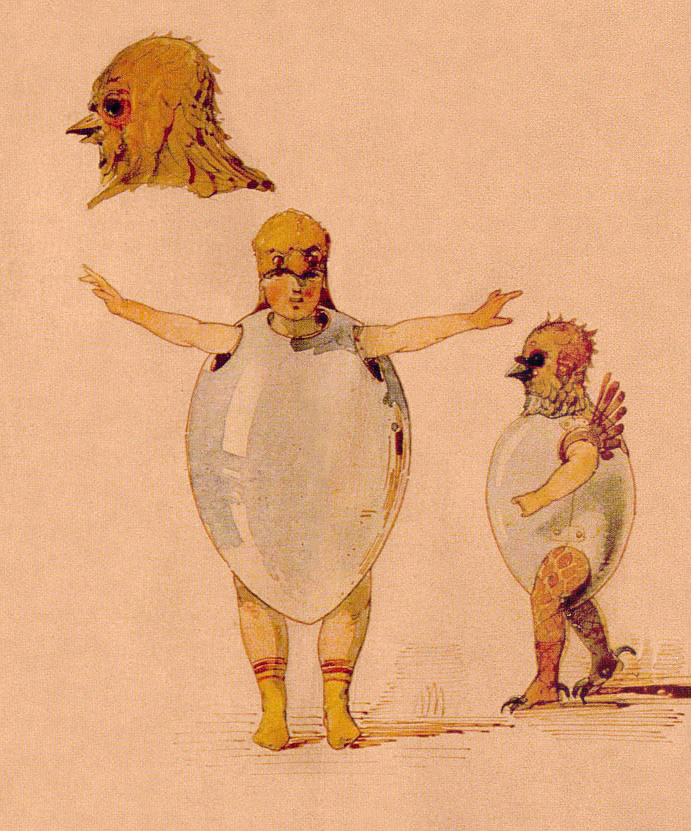

Ballet of Unhatched Chicks

Nosè presented a suitably agitated depiction of Hartmann's design for the ballet Trilby - the nervous movements of canary chicks. A Light, highly articulated touch suited this movement well.

"Samuel"

Goldenberg and "Schmuÿle" Two Polish Jews, Rich and Poor - Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuÿle -

were depicted rather graphically

'Rich'

'Poor'

Promenade Walking with some nervous anxiety

Limoges.

The Market (The Great News) Nosè

painted an excitable, argumentative provincial market life scene.

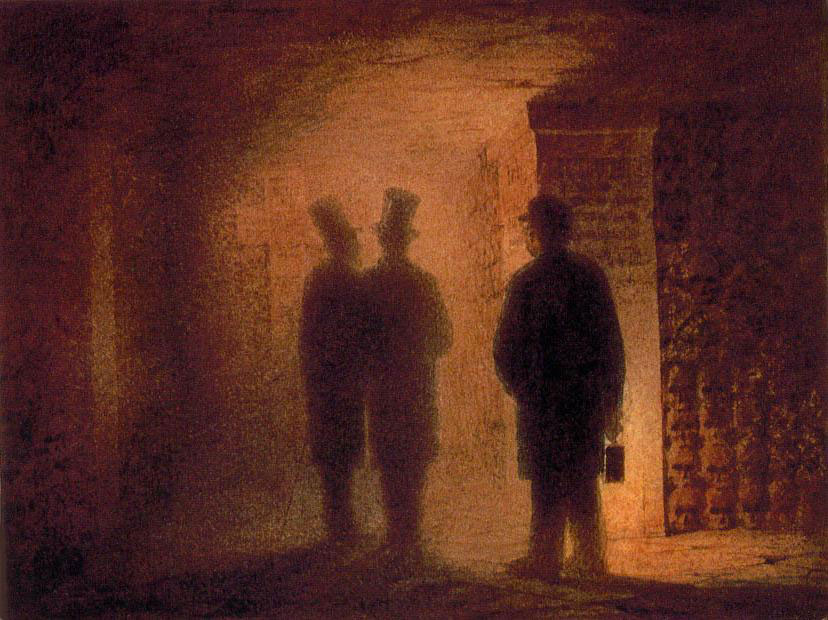

Catacombs (Roman Tomb) - With the Dead in a Dead Language

Nosè presented

the catacombs with a rather over-heavy, predictably mournful atmosphere. I

remember visiting them myself when living as a child in Rome many years ago

Hartmann, Vasily Kenel, and a guide holding the lantern

'Catacombae' and

'Cum mortuis in lingua mortua' from Mussorgsky's 'Pictures

at an Exhibition'

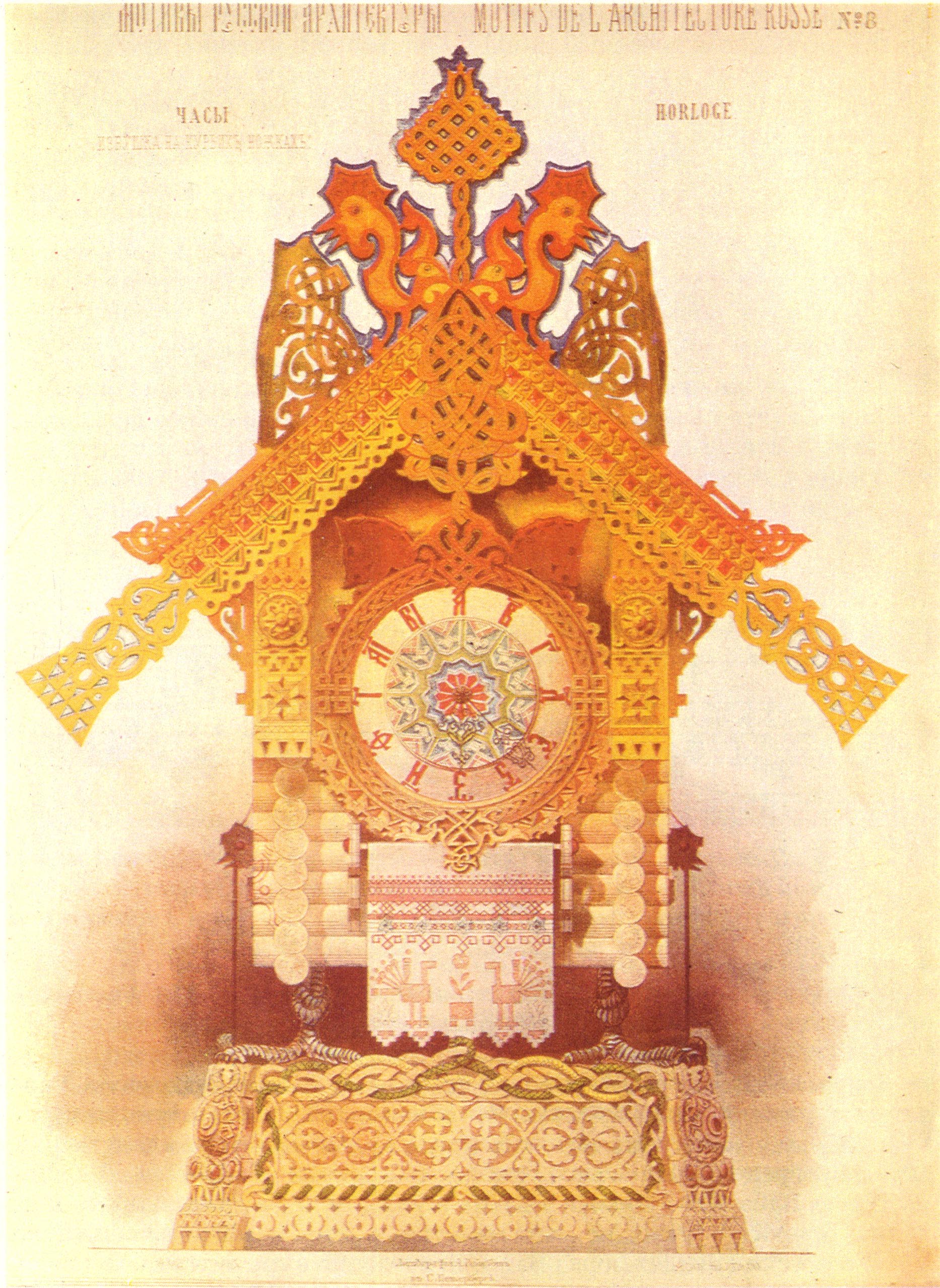

The Hut on

Hen's Legs (Baba Yaga) Nosè

with his formidable technique, painted the threatening, rather dramatically

alive portrait of an unpleasant fantasy creature. Hartmann's drawing depicted a

clock in the form of the ghastly Baba Yaga's hut perched on fowl's

legs.

The ghastly witch Baba Yaga

The Bogatyr Gates (In the Capital in Kiev) or 'The Great Gate of Kiev' Nosè constructed a formidable gate of power and majesty for us. His tonal weight is without harshness and his phrasing gave a massiveness that created a fine background to Orthodox carillons. He brought off this challenging sculpture in sound completely convincingly.

His

performance was very enthusiastically received by the 'distanced' audience.

Before his

encore he gave an address thanking Piotr Paleczny for the opportunity to play

in this historic venue especially during the pandemic and reminded us of his

enormous contribution as Artistic Director over twenty-five years.

He offered

the first encore to him - I did not recognize it and perhaps it was a piece of

his own composition.

The second encore was a tender, warm and longing interpretation of Brahms deeply affecting Intermezzo in A major - Andante teneramente Op.118

His third a delicate and brief Prelude by Ravel

His fourth encore was the heart-wrenching

Schubert Impromptu No.3 in G-flat

major: Andante D.899 performed with all the velvet touch, refined tone, great sensibility

and love this fine pianist is so capable of .....

FRIDAY, 14 AUGUST CHOPIN MANOR 4.00 pm

JAKUB KUSZLIK

Second Prize

X International Paderewski Piano Competition, Bydgoszcz – Poland 6th-20th November 2016

Jakub Kuszlik

courageously and generously took the place of Alexander Gavrylyuk at very short

notice. He is to be congratulated on his courage in the face of this pandemic.

This extract

is from a review of the Mozart Concerto phase of the outstanding X

International Paderewski Piano Competition, Bydgoszcz – Poland 6th-20th

November 2016 where he was awarded the Second Prize

Mozart Piano Concerto No

17 in G major K. 453

Mozart wrote

this work for his pupil Barbara Ployer in 1784. The two themes that open the

work are rather gentle in nature. The Andante was expressive

and charmingly played. In the spring of 1784 Mozart jotted down in his notebook

the song of a starling that he heard that was for sale. ‘That was beautiful’ he

allegedly commented. He purchased the dear bird and when it died he actually

buried it in the garden with a poetic epitaph. The final happy Allegretto movement

suggests so strongly Papageno in Die Zauberflöte. The coda as the

rumbustious excitement of the final act of a Mozart opera. A very good

performance. The jury became quite animated during this movement all tapping

away silently with their fingers, denied their opportunity to shine as

soloists. How Mozart is loved!

Robert

Schumann (1810-1856)

Kreisleriana Op.16 subtitled Phantasien für das

Pianoforte (1838)

He opened his

recital with one of my favourite works of romantic piano literature Kreisleriana

Op. 16 by Robert Schumann.

Madness or

insanity was a notion that throughout the composer's time on earth,

simultaneously attracted and repelled Schumann. At the end of his life he was

cruelly to fall victim to it. Kriesleriana was presented

publicly as eight sketches of the fictional character Kapellmeister Kreisler, a

rather crazy conductor-composer who was a literary figure created by the

marvellous German Romantic writer E.T.A. Hoffman. The piece is actually based

on the Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier and also the form of

an inventive grotesque satirical novel Hoffmann wrote with the remarkable,

translated title: Growler the Cat’s Philosophy of Life Together with

Fragments of the Biography of Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler from Random

Sheets of the Printer’s Waste.

The fictional

author of this novel Kater Murr (Growler the Cat) is actually

a caricature of the German petit bourgeois class. In a theme rather appropriate

in our times of gross financial inequalities, Growler advises the reader how to

become a ‘fat cat’. This advice is interrupted by fragments of Kreisler’s

impassioned biography. The bizarre explanation for this is that Growler tore up

a copy of Kreisler’s biography to use as rough note paper. When he sent the

manuscript of his own book to the printers, the two got inexplicably mixed up

when the book was published. Such devices remind one of Laurence Sterne in that

great experimental novel Tristram Shandy.

Schumann was

particularly fond of Kreisleriana. He was attracted to

composing a works in ‘fragmented’ form in the structural manner of this novel.

The use of the device of interrelated ‘fragments’ (as the

nineteenth century termed what we might refer to as

'miniatures') was employed by the Romantic Movement in poetry, prose and

music. Kreisler is a type of Doppelgänger for Schumann. This

was a favourite concept for the composer, who divided his own creative

personality between the created characters of Florestan and Eusebius. With the

unpredictable Kreisler as his alter ego, Schumann was able to indulge the

dualities of his own personality. The music swings violently and suddenly

between agitation (Florestan) and lyrical calm (Eusebius), between dread and

elation. The episodes in the piece describe Schumann's emotional passions, his

divided personality and his creative art. His tortured soul alternates with

lyrical love passages expressing the composer’s love for Clara Wieck. He used

and transformed one of her musical themes in the work.

1838 was a

disturbed time for Schumann. His marriage to this 'inaccessible love', the

piano virtuoso Clara Wieck, was a year ahead. At this time they were painfully petitioning

the courts for permission to marry and ignore her father's cruel social class

objections to the connection. They had known each other for ten years before

their eventual marriage in 1840. During this turbulent period of frustration,

Schumann’s compositions evolved in complexity. Their unbridled emotionalism and

adventurous structure confused musicians, audience and critics alike.

He originally

intended to dedicate the work to Clara, but wishing to avoid more calamitous

situations with her father, eventually dedicated it to his friend Fryderyk

Chopin. The polyphonic nature of the piece may have reflected a deep

understanding of Chopin's own style. The Polish composer

merely commented on the cover design of the score left on his piano. Even

Clara, on first acquaintance with the work, wrote: 'Sometimes your

music actually frightens me, and I wonder: is it really true that the creator

of such things is going to be my husband?' Even Franz Liszt was

challenged finding the work 'too difficult for the public to digest.'

This great

masterpiece of emotional and structural complexity, expresses much of the

quixotic mercurial temperament of Schumann's personality and the literary

elements of the story. The French literary theorist and Schumann-lover Roland

Barthes interestingly observed that Schumann composed music in discrete,

intense 'images' rather than as an evolving musical 'language', like a

succession of frames in a film. The composer was experimenting with the

timbre of piano sound. Without wishing to appear a 'crank', I feel it necessary

to say that on a piano of Schumann's period (he loved Clara's Conrad Graf

of 1838 from Vienna) the varied colours, timbre and textures of the

different registers suited the contrapuntal nature of composition. This would

have been rather more obvious on the older instrument than on the modern

homogenized Steinway.

Kuszlik produced a beautiful cantabile tone with some very sensitive, poetical nuanced moments from his sensitive touch. His attractive technique was well able to deal with the extensive keyboard demands. He grasped the emotional and structural complexity of this piece well enough to give it much of the challenging coherence it requires. However, such a temperamental and capricious work by Schumann (and the bizarre background story by E.T.A.Hoffmann) is difficult to present with great conviction and lucidity. I felt this unpredictable, spontaneous, quick-silver moody aspect of the composer escaped him somewhat in his feeling for the lyrical Eusebius qualities of the piece at the expense of the more energetic, fragmented driving, almost pathological qualities of Florestan. These matters are so often a question of balance.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849)

Piano Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58

The transition

to the Largo is deceptively easy to manage but was not sufficiently expressive. Here

we begin an exquisite extended nocturne-like musical voyage taken through a

night of meditation and introspective thought. This great musical narrative of

extended and challenging harmonic structure must be presented as a poem of the

reflective heart and spirit. I felt although tonally refined, Kuszlik could have

brought a more introspective quality with more direction rather than enveloping

us in a mellifluous dream world, however attractive, of little directional

focus. The Finale. Presto ma non tanto was certainly

powerful in its headlong rush. He approached this movement as rather a virtuoso

piano work than a rhapsodic narrative Ballade in character. Throughout the

sonata, although of course finely played, I kept wondering what Kuszlik was

trying to tell me about this work in any individual sense.

Tomaszewski

again who cannot be bettered:

Thereafter,

in a constant Presto (ma

non troppo) tempo and with the expression of emotional

perturbation (agitato), this frenzied, electrifying music, inspired

(perhaps) by the finale of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony…’

As an encore he played the Chopin Mazurka in C minor Op.30 No. 1 in an affectingly idiomatic and sensitive manner.

THURSDAY, 13 AUGUST CHOPIN MANOR 4:00 pm

PIOTR PAWLAK

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849)

Prelude in C sharp minor Op. 45 (1841)

I found the tempo hew adopted was rather on the slow side and

deliberate, bordering on the mannered and self-conscious. Am certain this is all

a matter of taste.

Impromptu in A flat major

Op. 29 (1837)

Impromptu in F sharp major Op. 36 (1839)

Impromptu in G flat major

Op. 51 (1842)

Fantaisie-Impromptu in C sharp minor Op. 66 (1834)

Pawlak then performed the

three Impromptus opused for print by Chopin. Andre

Gide wrote of them: The impromptus are among Chopin's most enchanting

works. The great Polish musicologist and Chopin specialist Mieczysław

Tomaszewski wrote of them: The impromptus offer us music without shade,

a series of musical landscapes prefiguring impressionism.

The autonomous Impromptu genre was not that well

established, even for Schubert, when Chopin composed his first but as the years

passed he gave the form his own particular identity. Pawlak gave a

fine performance with subtle fluctuations of mood, a feeling of

improvisation. They seemed to arise from internal meditation. Lacking in

any exaggeration or hysteria, the Fantaisie

Impromptu in C sharp minor Op. 66 (1834) requires a high degree of

virtuosity to make it into a charming and convincing work. Pawlak began in

a highly finished style. The middle section with the famous slow, reflective

nocturne I felt again Pawlak took expressively but just occasionally slowly

enough to verge on the mannered with added pleasant expressive flourishes. It

flows at a moderato cantabile tempo, weaving a sotto

voce melody in D flat major. A

virtuosic conclusion with nostalgic reminiscences.

Prelude B minor Op. 28

No. 6 (1838–39)

In a favourite prelude of mine, I felt he rendered the left hand

melancholic cantabile most affectingly in its singing legato under the

pulsing, repetitions in the right hand.

César Franck (1822-1890)

Prélude, Choral et Fugue, FWV 21 (1884)

Prélude. Moderato

Choral. Poco più lento – Poco Allegro

Fugue. Tempo I

This Franck work was well described by Adrian Corleonis as ‘an

elaborately figured, chromatically inflected, and texturally rich essay in

which doubt and faith, darkness and light, oscillate until a final ecstatic

resolution.’

After hearing a

piece by Emmanuel Chabrier in April 1880, the Dix pièces pittoresques,

Franck observed 'We have just heard something quite extraordinary --

music which links our era with that of Couperin and Rameau.' The

forms Prélude, Choral and Fugue here are clearly symbolic of

their Bach inspired counterparts. The motives are obviously related to the Bach Cantata 'Weinen,

Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen', and also the 'Crucifixus' from the

B minor Mass. César Franck transforms these with his own unique

solutions and cyclical form.

The influence of the organ and his many years composing sacred texts are

obvious here. The pianist Stephen Hough in a note remarked "Alfred

Cortot described the Fugue in the context of the whole work as 'emanating from

a psychological necessity rather than from a principle of musical composition'

(La musique française de piano; PUF, 1930)." The work was finally

premiered in January 1885.

Pawlak gave an

ambitious, tremendously virtuosic performance leading directly into it from the

Chopin Prelude. The performance indicated he was coming to serious terms with this great

work. However, I missed the opulent organ timbre, texture and density from the piano although there was

great expressiveness when required. The work must be commanded with a tone and

touch that are appropriately noble, tragic and grand in all conceptual respects,

raising deep spiritual emotions from this secular musical construction.

The nervously agitated toccata-like Prelude needed

deeper emotions of anguish and pain which would lead to true personal

redemption in the Choral. This work is a great spiritual

journey from darkness into the light of dawn. Finally in the complex and

embattled Fugue, suffering is resolved into the

triumphant Choral theme once again – like a great chiming of

bells. Certain musical goals cannot be achieved by technique alone. These profound

emotional and spiritual musical demands (quite apart from the keyboard challenges)

are a tall order for any young heart to encompass, untrammeled as it likely is

by the tigers of experience.

Leopold Godowski (1870-1938)

Passacaglia in B minor

(1927)

Even to approach the study of this work, committing it to memory, expresses the powerful character mettle of this young pianist. The immense, Passacaglia, hewn from intimidating musical granite, was written in 1927 in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the death of Franz Schubert. The work is subtitled '44 Variations, Cadenza and Fugue on the opening theme of Schubert's Unfinished Symphony'. The piece has earned a reputation as being among the most difficult in the repertoire, perhaps because of a passing ironic reference by the pianist Vladimir Horowitz that it required six hands to play it and he would give up! Pawlak gave a commanding, passionate and breathtaking performance of this immense work of supreme difficulty which surely cements his reputation as one of the most promising of the young generation of Polish pianists. Do listen to the overwhelming Youtube recording of this Mont Blanc musical edifice once again!

As an encore he brilliantly

played the third movement, Allegro con brio ma non leggiere, of the Prokofiev

4th Piano Sonata in C minor Op. 20

WEDNESDAY, 12 AUGUST CHOPIN MANOR 8:00 pm

PHILIPPE GIUSIANO

Chopin (1810-1849) – Nocturnes Op. 48 (1841)

No. 1 in C minor

Tadeusz Zieliński felt the melody of this Nocturne ‘sounds like a lofty, inspired song filled with the gravity of its message, genuine pathos and a tragic majesty’. With every bar, the melody moves closer to the point of culmination, before plummeting downwards in a tense, expressively rhapsodic recitative and immersing itself in the contemplative sounds of a chorale. The chorale grows in strength, despite the fact that the violent music of double octaves forces its way in between its chords. André Gide spoke of ‘the sudden irruption of […] wind-blasts’ and ‘a triumph of the spiritual element over the elements unleashed at the beginning’.

No. 2 in F sharp minor

The atmosphere is created by the first two bars followed by the most affecting melody. Tomaszewski writes 'the impression might be that it will last forever.'

‘What is most exquisite and most individual in Chopin’s art, wherein it differs most wonderfully from all others,’ noted André Gide ‘I see in just that non-interruption of the phrase; the insensible, the imperceptible gliding from one melodic proposition to another, which leaves or gives to a number of his compositions the fluid appearance of streams.’ A characteristic of Chopin during the 1840s, in his last, reflective, post-Romantic phase. This is the source of Wagner’s unendliche Melodie Tomaszewski reveals with his unparalleled Chopinesque perceptions.

Guisiano brought these Nocturnes off persuasively well but I felt his 'classical' restraint rendered them to be occasionally lacking in gestures of true depth and character. The F sharp minor endless cantabile song could have been more romantically ardent and poetic rather than carefully eschewing any hint of sentimentality. Yet the conclusion was as tender and eloquent as a dream.

I am afraid I was not sufficiently moved by the depth of expression in this performance of the Barcarolle in F sharp major Op. 60 (1845–46). The work is a charming gondolier's folk song sung to the swish of oars on the historic Venetian Lagoon or a romantic canal, often concerning the travails of love. I understand that Guisiano restrains the romanticism of his expressive capabilities but in this case....

The Fantaisie Impromptu in C sharp minor Op. 66 (1834) requires a very high degree of virtuosity to make it into a charming and convincing work. The middle section that is so famous is reminiscent of a slow, reflective nocturne. It flows at a moderato cantabile tempo, weaving a sotto voce melody in D flat major. Again this somewhat patrician detached expressiveness prevailed which is not really the way I conceive of this work. As I have said so many times 'We all have our own Chopin!'

The difficulties

concealed in the Andante spianato and Grande Polonaise in E flat

major Op. 22 (1834–5) are easy to underestimate. Chopin often performed the

Andante spianato (smoothly without anxious tension) as a separate

piece in his rare recitals. It has both the character of a nocturne and a lullaby

and as such the tender expressiveness could have been more dwelt upon I think

than the sentiment Guisiano adopted. His cantabile tone was attractive but I

felt there is a deeply affecting simplicity

here which can surely be explored with more yearning phrasing.

The Grande polonaise brillante with its opening 'Call to the Floor' as if on horns and its super glittering style brillante is such a dramatic gesture. Hardly anyone playing Chopin waltzes has any idea of ballroom dancing in the nineteenth century. Chopin in his youth was mad about dancing, a fine dancer and also an excellent dance pianist playing into the small hours, hence his need for 'rehab' at Bad Reinherz – now Dusznki Zdrój. Certainly Chopin waltzes are not meant to be danced but the sublimated idiom remains. Chopin waltzes nearly always open, except say the Valse triste, with an energetic and declamatory fanfare or 'call to the floor' for the dancers. A slight pause and then the scandalous Waltz begins.

The essential nature of the style brilliant, of which the Grand Polonaise Brillante Op.22 is an essential and outstanding representative of Chopin’s early Varsovian style, seems rather a mystery to modern pianists who are not Polish. Jan Kleczyński writes of this work: ‘There is no composition stamped with greater elegance, freedom and freshness’. The style involves a bright, light touch and glistening tone, varied shimmering colours, supreme clarity of articulation, in fact much like what was referred to in French as the renowned jeu perlé. Giusiano came quite some way along that road certainly - but there are also vital expressive elements of charm, grace, taste, affectation and elegance to be considered too. The work is a fascinating piece of theatre which perhaps is as this work should be considered in many respects. It is not deeply philosophical but an utterly enjoyable brilliant confection written by a high-spirited young Pole named Fryderyk Chopin, a lover of dancing and acting. One must not forget that Chopin astonished Vienna by his pianism but perhaps even more by the elegance of his princely appearance.

INTERMISSION

Now for some rarely performed works. Ignacy F. Dobrzyński (1807-1867) was born on former Polish territory in Romanów, in former Volhynia in the Russian Empire, but now known as Romaniv, Zhytomyr Oblast in Ukraine. He first studied music with his father Ignacy, a violinist, composer and music director. In 1825 he studied in Warsaw with Józef Elsner privately, then in 1826–28 at the Warsaw Conservatory, where he was a fellow pupil of Fryderyk Chopin. Elsner commented on the two : 'Chopin - a remarkable talent [szczegolna zdolnosc] genius etc....Dobrzynski - an uncommon talent...much talent [zdolnosc niepospolita...wiele zdolnosci].' A committed Polish patriot he composed the arrangement of the Dąbrowski Mazurka which has since become the Polish national anthem. In 1835, he won second prize in a composition competition for his Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 15. This symphony was later called 'Symphony in the Characteristic Spirit of Polish Music' and movements were conducted by Mendelssohn. Dobrzyński toured Germany as a pianist, wrote piano pieces and also conducted opera.

A remarkable challenge for Giusiano to learn these piano pieces, all quite unfamiliar to me. These are piano miniatures in the style of Maria Szymanowska. I can only give my subjective impressions of what I discovered to be not particularly inspired pieces but pleasant on the ear for the salon. The Introduction, Thème original varié in B flat major Op. 22 (1833) I found pleasant enough in typical late classical variation form of the period. Some of the variations I found charming and ingenious. The Nocturne in G minor Op. 21 No. 1 (1833) I felt to be particularly delicate and affectingly poetic, pleasantly reflective of tender romantic emotions. Of the two Mazurkas Op. 37 (1840) No. 1 in F major was distantly reminiscent of Chopin as was No. 2 in A minor. I began to be aware of the canyon that yawns between musical talent and genius, that between Dobrzyński and Chopin. This was confirmed by the Hommage à Mozart – Fantaisie sur des thèmes de l’opéra Don Giovanni de W.A. Mozart in A major Op. 59 (1850). Both in structure and utilization I was of course reminded of the brilliant Chopin Variations in B flat major on ‘Là ci darem la mano’, Op. 2 - Chopin’s reaction to Mozart's Don Giovanni. Thanks to these Variations, Chopin’s fame spread across central Europe.

As a student of the Main School of Music, Dobrzyński had received a compositional task from Elsner to write variations for piano with orchestral accompaniment. Guisiano could have approached this with a great deal more sense of theatrical and operatic fun with his styl brillant, engaging the audience in its humorous twists and turns. To quote Schumann as an analogous case 'Almost Too Serious,' (Fast Zu Ernst) from Kinderszenen.

His encores were at first a refined and most expressive Chopin Nocturne in C-sharp minor Op.posth. His second encore was a delightful and sensitive rendition of the Chopin Impromptu in A-flat major Op.29. His final encore for this highly enthusiastic audience was the Polonaise in A-flat major Op. posth.

Clearly from the warm reception of this pianist by Duszniki audience, this is a style of playing Chopin that appeals greatly. The introduction of unfamiliar works by his fellow pupil and Polish patriot Dobrzyński added to the enthusiastic response.

WEDNESDAY, 12 AUGUST CHOPIN MANOR 4:00 pm

ZUZANNA PIETRZAK

Alexander Scriabin

Sonata-Fantasy in G sharp minor Op. 19

(1898)

The Scriabin Piano Sonata-Fantasy No. 2

in G-sharp minor took the composer five years to write and published in

1898. This alluring piece is in two movements and is particularly popular. The

piece is widely appreciated and is one of Scriabin's most popular pieces.

The programme reads: 'The first section (Andante) represents the

quiet of a southern night on the seashore; the development is the dark

agitation of the deep, deep sea. The E major middle section shows caressing

moonlight coming up after the first darkness of night. The second movement (Presto) represents the

vast expanse of ocean in stormy agitation.'

The Andante was an impressionistic, expressively harmonic

interpretation. Gentleness and colour with a rather fluctuating dreamlike tone

quality although occasionally a heavy touch. The Presto certainly gave

one a painting of 'stormy agitation' on the ocean but the tempo felt slightly

rushed on occasion.

The Chopin Nocturne in E minor Op. 72 No. 1 (1827) is not dated

with certainty. It has the rather melancholy characteristics of E minor which

Pietrzak expressed feelingly - of sighs accompanied by

only a few tears. There has been

speculation that it may be the last of his nocturnes as it possesses the characteristics of Chopin's so-called

'late style'.

Mazurkas Op. 41 (1838–39)

No. 1 in E minor

Chopin composed mazurkas all his life. The great Polish musicologist

Tomaszewski tells us that In the E minor Mazurka we hear a distinct

Polish echo: the melody of a song about an uhlan (cavalry) and his girl, ‘Tam

na błoniu błyszczy kwiecie’ [Flowers sparkling on the common] (written by

Count Wenzel Gallenberg, with words by Franciszek Kowalski) – a song that

during the insurrection in Poland had been among the most popular. Chopin

quoted it almost literally. Pietrzak captured the nostalgia of remembrance

successfully but when Chopin heightens the drama to the tragic, I felt emotions

dominated and her tone became rather too weighted in contrast before returning

to melodiousness of the close.

No. 2 in B major

The Mazurka

in B major was most likely composed at Nohant, although bears a feeling of

the period on Majorca. ‘The first four bars and their repetitions’,

said Chopin, ‘are to be played in the style of a guitar prelude,

progressively quickening the tempo’. Next to the piano, the guitar was Chopin's favourite instrument and the

one that his teacher Elsner chose to serenade him when he left Warsaw by the

Wola gate in 1830. If one thinks of the sound and timbre of the guitar a different approach may have

offered itself.

No. 3 in A flat major

She brought the euphonious

intonations and rhythms and heard undoubtedly in the Cuyavia region, in

north-central Poland, situated on the left bank of Vistula. The work

opens piano which would have given her more contrast and room to expand

into forte less stridently.

No. 4 in C sharp minor was

composed during the first summer at Nohant. It is one

of the most beautiful mazurkas, resembling a miniature dance poem. It seems to

arise out of nothing, and ends the same way. Stephen Heller noted: ‘What

with others was a refined embellishment, with him was a colourful bloom; what

with others was technical fluency, with him resembled the flight of a swallow.'

Although attractive, the poetry of the reminiscence of Chopin could have been

caressed more lovingly at a slower tempo and yet allow the strong mazurka

rhythm to develop in definition as memory does, in contrast. The conclusion then

returns us to the dream from which the piece originally materialized.

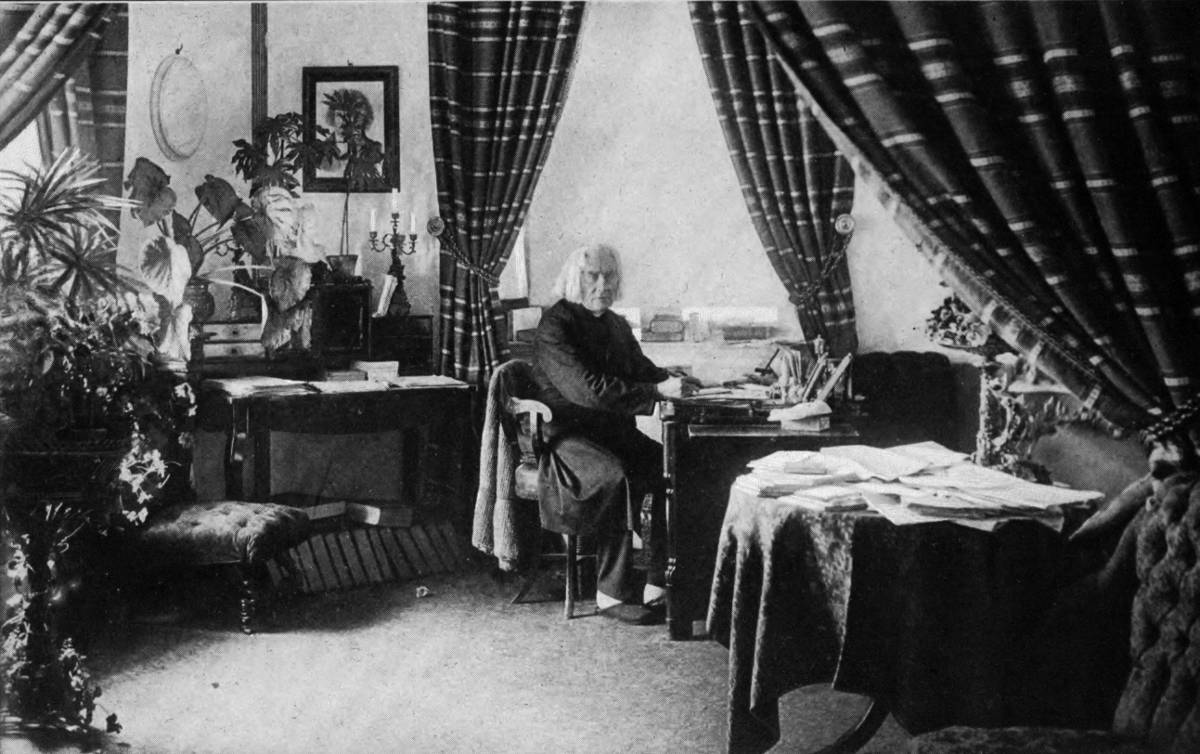

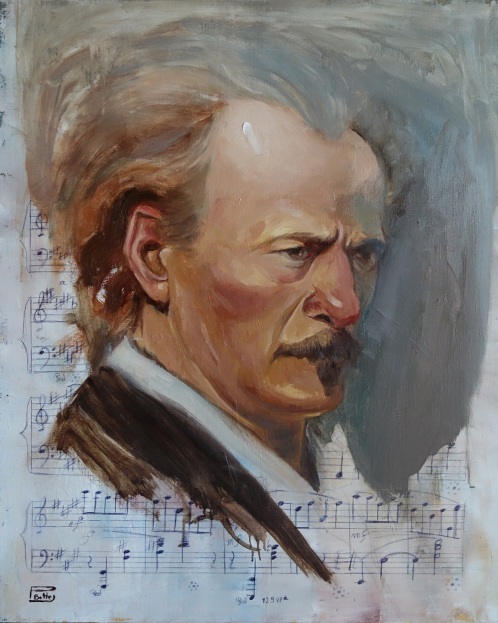

Liszt in his Atelier at Weimar

Ferenc Liszt – Sonata in B minor S.178 (1852–53)

The second half of the recital was devoted entirely to the Liszt B

minor Sonata. The performance of this sonata is an extraordinarily bold and

courageous choice for any young pianist.

This famous Sonata was published by Breitkopf & Härtel in

1854 and first performed on January 27, 1857 in Berlin by Hans von

Bülow. It was attacked by the German Bohemian music critic Eduard Hanslick

who said rather colourfully ‘anyone who has heard it and finds it beautiful

is beyond help’. Among the many divergent theories of the meaning of this

masterpiece we find that:

- The Sonata is a

musical portrait of the Faust legend, with “Faust,” “Gretchen,” and

“Mephistopheles” themes symbolizing the main characters. (Ott, 1981;

Whitelaw, 2017)

- The Sonata is

autobiographical; its musical contrasts spring from the conflicts within

Liszt’s own personality. (Raabe, 1931)

- The Sonata is

about the divine and the diabolical; it is based on the Bible and on John

Milton’s Paradise Lost (Szász, 1984)

- The Sonata is

an allegory set in the Garden of Eden; it deals with the Fall of Man and

contains “God,” “Lucifer,” “Serpent,” “Adam,” and “Eve” themes. (Merrick,

1987)

- The Sonata has

no programmatic allusions; it is a piece of “expressive form” with no

meaning beyond itself. (Winklhofer, 1980)

The manner in which a pianist opens this

masterpiece tells you everything about the conception that will evolve.

The haunted repeated notes Pietraszak produced were of an eloquent

duration (a terrible battle lies in wait for pianists here - Krystian Zimerman

drove his recording engineers mad repeating it hundreds of times before finally

being satisfied). Her duration and dynamic boded well for the outcome of

the sonata. It is inevitable with a young artist that virtuosity

(getting around the fiendish notes of Liszt) comes sometimes at the expense of

expression.

Just to have this vast work in your fingers is a massive achievement but

what you do with this is another matter altogether, what you have to

say about this work. This is a profound piece, too often played as

some type of hectic fantasy or impassioned dream fantasy although that was not

the case here.

The sonata is actually in many respects a philosophical dialogue between

different fundamental aspects of the human spirit as symbolized by Faust,

Mephistopheles and Gretchen. Liszt was tremendously influenced by literature

and poetry in his compositions and in particular Goethe’s Faust,

the dramatic spiritual battle between Faust and Mephistopheles with Gretchen

hovering about as a seductive, lyrical feminine interlude. And the whole is a

far more complex musical and structural argument than my rather trite account

would indicate.

Pietraszak gave an at times emotionally moving, idiomatic and dramatic

account of this formidable sonata. She allowed her phrases expressively to breathe

and flower. Her tone tended to became rather heavy in the more emotionally

impassioned passages, but there was moving poetry in lento passages here too. The mighty Fugue was polyphonically transparent and noble in dimension. The pianissimo conclusion took us into a dimension beyond. To begin analyzing

her approach in detail here, would be to diminish the communication of her well

integrated conception of this mighty edifice.

However, where was the smell of sulphur and the diabolical? Reading Byronic literature of the period that reflects the evolution of this remarkable life narrative, would greatly enhance the pianistic vision through subtle stimulation of the musical imagination.

A notably promising young pianist with a

significant future ahead.

Encores were a sensitively performed Bach Largo from the

Harpsichord Concerto No.5 in F minor BWV 1056 . This was followed by a movingly phrased and poetic Paderewski Nocturne.

TUESDAY, 11 AUGUST CHOPIN MANOR 8:00 pm

JAN JIRACEK VON ARNIM

I have been aware of this pianist and professor for some years and have always

been full of admiration for his knowledge, friendliness and wit. Last time I heard him play was in 2007 in Duszniki Zdrój when he gave

a particularly fine performance of Schumann's Faschingsschwank aus Wien

and we discussed Michelangeli and his interpretation. He took Masterclasses in

Duszniki in 2011 and then was a jury member for two weeks at the Paderewski

Competition in Bydgoszcz in 2013.

He opened his carefully planned recital with the first two of Schubert's

Drei Klavierstücke D 946 (1828). These are such revelations

of his soul and such intimate works from the last year of his life (1828). They

are lyrical pieces where the expressiveness has been extremely concentrated. I

felt von Arnim approached them as an affirmation of life and the energy he

brought was transparent and polyphonic. No. 1 in E flat minor had

the character of a lyric song and I felt even witty and ironic in parts. I felt

he had a great deal to tell us in these works with a significant degree of

dynamic variation. His tone and touch were refined, elegant and classical - so

suitable for Schubert. In No. 2 in E flat major again his variation in

touch and tone were captivating. The emotional disturbance within the piece was

rather threatening in character and the eloquent phrasing and sense of

structure spoke volumes concerning the fluctuating nature of Schubert's inner

emotional life. Von Arnim predominantly allows the music to speak with modest

contrasts and subsumes his own personality to be in complete service to the

music itself. This is welcome in a celebrity straining world.

The one of my favourite Beethoven sonatas. Many of his piano sonatas have 'titles'. However the rather revolutionary E-flat major Op. 81a is the only one inspired by a solid historical event. This was the flight from Vienna of his patron the Archduke Rudolph and the nobility as the Napoleonic pantechnikon irresistibly approached the defences of Vienna.

Beethoven began the first movement in May 1809, following the departure of the Archduke and just days before Vienna was placed under siege by Napoleon. Beethoven sheltered in a cellar with a pillow over his head to protect his hearing. The remaining two movements were written in January 1810, after the Archduke returned.

The dedication

reads: 'On the departure of his Imperial Highness, for the Archduke Rudolph

in admiration' although he privately he wrote 'written from the heart'.

In the light of the political situation, one can readily understand how angry Beethoven

was when his publisher, for reason of sales, gave it the French title Les

Adieux rather than his own

German Lebewohl . In his following sonata (Op. 90) he rejected

Italian tempo markings as Napoleonic, and later even replaced the Italian word pianoforte

with the German Hammerklavier.

Von Arnim approached the Beethoven Sonata in E flat major Op. 81a

“Les Adieux” (1809-10) with much sensibility and interpreted the Adagio –

Allegro (Lebewohl) with all the melancholy that the situation demanded,

dwelling on the lamenting three note melody, a horn call symbolizing in poetry

the pain of distance, solitariness and memory. The Allegro (begun

without pause) was expressed with a great variety of articulation and it was

clear he listened and savoured the evolving harmonies. His tone and touch were

slightly restrained and captured the 'classical' rather 'dry' ambiance of the

keyboard sound of the period. Judicious pedaling was of great assistance here.

This meant transparency which revealed many 'hidden' details in the writing. The

coda gave one a sense of separation and departure. His surges of dynamic

indicated Beethoven as a composer on the cusp of Romanticism, perhaps even

forging it.

I felt the Andante espressivo (Abwesenheit) was rather too positive in tone to be deeply

poetic and yearning, cultivated with a deep sense of loss. I wanted to feel

more of the heart aching after the parting. Yet there was much sensibility here

and even the strong emotion of resentment and anger at such an unfolding of

destiny. The Vivacissimamente (Das Wiedersehn) began with a sudden

explosion of the joy of return (slightly too sudden?). Here in this movement we

were given the full Beethovenian exuberant energy by von Arnim. Huge gestures of simple

happiness without complex sentiment. The quiet development seems to indicate

feelings beyond words as did the slightly melancholic conclusion. A completely

satisfying performance, possibly understandable as it was given by a fine

Viennese pianist. Given the universality of Beethoven and our distance from the historical source, one can still easily apply the sentiments within this great sonata to one's modern private life.

INTERMISSION

The careful planning of this recital then began to reveal itself in the

key relations and their extra-musical associations. The Schubert Impromptu

in A flat major D 899 (1827) would be followed by the Chopin Ballade in

A flat major Op. 47 (1841). In the nineteenth century this was considered a

rather melancholic key. There are many emotional links I feel between the

sensibility of Schubert and Chopin. I found this familiar Impromptu possessed

of an alluring, rippling tone with fine articulation.

This was a fine performance of the Chopin Ballade in A flat major

Op. 47 with 'narrative' musical force. Penetrating the

expressive core of the Chopin Ballades requires an understanding of the

influence of a generalized view of the literary, musical and operatic balladic

genres of the time, something von Arnim understands well. In the structure

there are parallels with sonata form but Chopin basically invented an entirely

new musical material. I have always felt it helpful to consider the Chopin

Ballades as miniature operas being played out in absolute music,

forever exercising one's musical imagination. The work contains some of the

most magical passages in Chopin, some of the greatest moments of passionate

fervour culminating in other periods of shattering climatic

tension.