For the first time, a musical expedition through the complete solo piano works of Fryderyk Chopin played on an 'Erard' instrument of 1849 by the sublime Tatiana Shebanova

This journey I am taking through Chopin with the Russian pianist Tatiana Shebanova and her intimate relationship with the 1849 Erard is a truly memorable musical experience. I sincerely suggest you 'push the boat out', purchase this set and accompany me on this remarkable musical expedition, a voyage written in the mind and engraved on the soul.

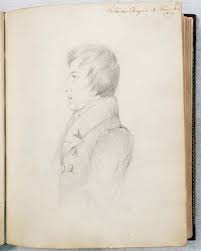

A chronological portrait of Chopin is laid out before us, a landscape to relive the flowering of his genius from innocent boyhood to fraught maturity.

I am a literary travel author and assure you this is one of the greatest journeys I have undertaken - not physically of course but through another dimension of consciousness, the soundscape of the musical heart and mind. One cannot help but reflect on the shift of sensibility aroused on an Erard compared to a modern virtuoso performance on the 'unlimited' dynamic of a Steinway, Yamaha or Bösendorfer. There is no choice offered here - simply a different or additional frame of musical reference.

These recordings are the accumulated vision of a remarkable musician and pianist, playing at the time of her life close to the ultimate destiny of us all. These interpretations and sound suffuse her Chopin with the deepest of life truths.

[Written 17th May 2021 - two weeks after setting out on this expedition]

https://sklep.nifc.pl/index.php?produkt=2_171

The Russian pianist Tatiana Shebanova who lived in Poland for many years was one of the

first pianists I heard play works by Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) in concert in

Poland in 1992. It was an overwhelming musical experience for me. I was taken

along the virtuoso track of a great individual vision of the

composer, expressively distant from many 'standardized'

live interpretations and recordings.

This music of yearning nostalgia

and fierce resistance was appropriately performed on this occasion not in a

concert hall but in the Officer Cadets' School in Łazienki Park in

Warsaw.

|

| The Great Annexe, Łazienki Park, Warsaw. |

Toward the

end of the 17th century, a smaller building stood in the place of today’s

Great Annexe (Officer Cadets' School) in

The November Uprising 1830 - The year Chopin left Poland never to return ...

On 29 November 1830, a group of conspirators left the building of the Officer Cadets' School in Łazienki (Podchorążówka) and seized control of the nearby Belvedere Palace, the seat of the commander of the Russian forces, Grand Duke Konstantin. The group was led by sublieutenant Piotr Wysocki. This is how the November Uprising began in the Royal Łazienki.

|

| Near the Officer Cadets' School stands a bust of Piotr Wysocki (1797-1875) - a national hero of Poland. |

On this occasion I also had the good fortune to meet the late extraordinary and renowned Polish journalist and music critic Jerzy Waldorff who signed my copy of his outstanding The Rest is Silence, a descriptive catalogue of the headstones and monuments in Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw. This place of rest is in many ways the most original part of the city to survive the conflagration of WWII. Naturally we spoke of the music of Chopin and Shebanova, but also surprisingly, that of Francois Couperin.

Tatiana Shebanova (1953-2011) was born in Moscow and studied at the Central Music School of the Moscow Conservatoire under Tatiana Kestner. She graduated with a gold medal in 1976 after studying under professor Victor Merzhanov. She was awarded 2nd prize after Dang Thai Son at the 10th International Fryderyk Chopin Competition in Warsaw in 1980. This led to a distinguished international career. She often performed duets and concertos with her husband Jarosław Drzewiecki and son Stanisław Drzewiecki.

Her life was tragically cut short by leukemia not many years after her discovery of the intimate affinity she possessed for the colors, timbre, refined elegance and graduated power of the period instruments by the Parisian pianoforte builder Sebastian Erard. It is the greatest good fortune and a testament to her monumental courage, sensitivity and perseverance that we have this remarkable set of recordings released exactly on the tenth anniversary of her death on 1st March 2011 surely not coincidentally, an anniversary of the composer's birth.

'Tatiana defends herself against boundless sorrow and wards off the loss of hope' affectingly writes Stanisław Leszczyński, Artistic Director of the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute.

There are 14 CDs in this remarkable set performed on a fine Erard instrument of 1849 with an informative booklet by the musicologist and former Director of the Fryderyk Chopin Institute, Grzegorz Michalski. The sound engineering by the brilliant Lech Dudzik and Gabriela Blicharz is outstanding. This box set includes nearly all Chopin's solo piano music apart from the chamber works and songs.

Of course, as many of you may already know, the Pleyel (grand and pianino) and not the Erard was Chopin's sine qua non. However he did praise the beautiful tone and resonance of the Erard. This instrument was deemed more suitable for the public, extrovert stage presence of Liszt 'playing for thousands'. Chopin emphasised intimate bon gout and had a preference for small da camera performances on the less declamatory and mellow Pleyel. However Chopin much envied the Liszt performance of his Etudes on the more robust Erard.

Chopin interestingly observed of this instrumental difference:

'If I am not feeling on top form, if my fingers are less than completely supple or agile, if I am not feeling strong enough to mould the keyboard to my will, to control the actions of keys and hammers as I wish it, then I prefer and Erard with its limpidly bright, ready-made tone. But if I feel alert, ready to make my fingers work without fatigue, then I prefer a Pleyel. The enunciation of my inmost thought and feeling is more direct, more personal. My fingers feel in more immediate contract with the hammers, which then translate precisely and faithfully the feeling I want to produce, the effect I want to obtain.'

(As recounted by Antoine François Marmontel (1816-1898) French pianist, composer, teacher and musicographer)

The recordings take you on a journey through his entire compositional career for the instrument. They have been divided into chronological groups, the manner in which I will approach this review.

A true jewel

box of uniquely inspired musical performances of Chopin by an artist of awesome

courage, poetic soul, tender sensitivity and spiritual strength who has

overcome through music the final barrier life erects for us.

The alluring

sound of the 1849 Erard will surprise you all ..... the unique qualities

of the period instrument so clearly inspired her to even greater musical

heights.....a poignant achievement. It is not as if I am advocating the Erard

above a Steinway, Yamaha or Bösendorfer. The emotional

landscape is simply rather different, not better or worse, on a period piano

such as a fine Erard or Pleyel.

CD 1 – NIFCCD 121

Youthful works (1817–1827)

When considering the youthful works one must consider the musical background of his teachers and formative influences. At first, until the age of 11, the Bohemian-born Polish pianist, violinist, teacher and composer, Wojciech Żywny (1756-1842) who inculcated Chopin's enduring love of polyphony and J.S.Bach. Then until 1830, Józef Elsner (1769-1864), the Silesian composer, music teacher, and music theoretician much influenced by German pedagogical considerations and theories. He was intimately familiar and implemented in his teaching the musical works and writings of the Polish poet and Slavophile Kazimierz Brodziński (1791-1835), music and treatises of C.P.E Bach, the composers Wincenty Ferdynand Lessel and Hummel among many others. Elsner also deeply admired and implemented the 'organic' educational beliefs of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827), the Swiss pedagogue and educational reformer who exemplified Romanticism.

This is a mere music review, but if you as the reader wish to fully understand the vital formative cross-cultural, interdisciplinary and contextual influences on Fryderyk Chopin, please obtain and read Music in Chopin's Warsaw (Oxford 2008) by the brilliant and enlightening Halina Goldberg, Professor of Music (Musicology) at the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, Bloomington.

The earliest Polonaises composed when Chopin was around seven years old are an innocent delight to my mind, already revealing his supreme gift for melody and harmonic adventurism. Shebanova elevates these works, naturally not to great 'masterpieces', but works full of simplicity, charm and civilized allure. It is hardly surprising that he was considered the Polish Mozart. The early rondos (the original harmonies of the Rondo in C Minor Op.1 of 1825 are fluently expressed), various mazurkas and the elegant A-flat major Waltz (WN 28 - 1827-1830) are all here in addition to the refined Ecossaises (1826?-1830?). The Rondo à la Mazur (1826) is a remarkably precocious piece that Shebanova performs with great sensitivity, a velvet touch, a mastery of the mazurka/oberek rhythm and style brillante articulation. These early works are a balm to any troubled soul ...

|

| Warsaw from Praga during the youth of Fryderyk Chopin - Bernado Bellotto (1721-1780) |

CD 2 – NIFCCD 122

Youthful works (1827–1830)

There is serious

discussion whether the structurally mature and emotionally yearning Nocturne

in E minor Op.72 (1827-1830) could possibly be a juvenile piece although

chronology points to this. On the Erard it is deeply moving

with Shebanova.

The major work on this disc is

the almost forgotten Sonata in C minor Op.4 (1827-1828) which in many ways

is a dissonant, harmonically experimental work of great originality that has

been overshadowed by his profoundly expressive later sonatas.

Shebanova made me listen to this late student work closely and marvel at the

musical, compositional discoveries and experiments Chopin engaged in. Her

searching, exploratory, almost improvisatory performance (of the Larghetto) should

cause the sonata to be included far more often on concert programmes and

in competitions.

One can hear the gently rising

strength of national resistance, not yet 'heroic', in the Polonaise

in F-minor Op.71 No.3 (1829?) I cannot remember ever having heard

the Mazurka in D major, Op. Posth. No.55 (1829)! There is something

caressing, gently seductive and feminine in subtlety in Shebanova's

interpretation of the Waltz in B minor Op.69 No.2 (1829) and

the Waltz in D flat major, Op.70 No.3 (1829).

CD 13 – NIFCCD 133

Works with orchestra

The Fantasy on Polish

Airs in A major Op.13 (1829) is taken by Shebanova at a reflective,

almost nostalgic tempo of great tenderness interrupted by

moments of sparkling youthful exuberance. The Variations in B flat major

on 'Là ci darem la mano' from the opera Don Giovanni by

Mozart, Op.2 (1827-1828) was finely performed but was slightly in need of a more

relaxed and festive style in keeping with the opera buffa and Il dissoluto.

The Rondo à la Krakowiak in F major, Op.14 (1828) has such energetic krakowiak rhythm and melody delivered by Shebanova in a glistening style brillante that was completely convincing on the Erard. The Viennese in August 1829 marveled at the beauty of the second performance of Chopin's composition. Wild response followed the Warsaw performance the following year. The Andante spianato (1830-1836) is lyrical and poetic tenderness prevails overall. From this heartfelt performance one can understand why Chopin often performed the piece on its own. The Grande Polonaise brillante that follows is certainly depicted by Shebanova in the style brillante at its apogee. An exciting and accurate rendition of this challenging youthful work.

CD 14 – NIFCCD 134

Piano concertos (1829–1830)

The two concertos with Shebanova are two beautiful, poetic accounts of them. She revealed extreme sensitivity, musicality and a profound understanding of what Chopin's favourite pupil Marcelina Czartoryska referred to as le climat de Chopin. The timbre of the Erard blends so well with the Orchestra of the 18th Century under Frans Brüggen. The period instrument orchestra directed by this conductor has always seemed to me the perfect ensemble stylistically and in the quality of its early nineteenth sound to express the spirit and essence of the piano concertos of Chopin. Really I have nothing to say that might disturb the virtuoso flight Shebanova takes us upon, up into the unblemished azur of illusioned love.

CD 3 – NIFCCD 123

Between Paris and Warsaw (1829–1831)

There is some extraordinarily beautiful music on this disc which illustrates the uniquely expressive aspects of the period Erard. The pianissimo possible on the Pleyel and Erard has a gossamer, lace quality to it under sensitive fingers that understand and feel the exquisite emotional suggestiveness. The wash of colour through the registers that accompanies the instrumental sound, due to inefficient damping (so unlike a Steinway or Yamaha), is like a watercolor background to a painting of an emotional landscape.

The profoundly moving Lento con gran expressione or the Nocturne in C sharp minor (1830) is one of the most intimate and subtle expressions of melancholic nostalgia and yearning in all Western solo piano music. Shebanova cultivates a delicate pianissimo opening as if the work hesitantly materializes like a wraith from utter silence ... such sensitive, reflective meditative musical poetry on the nature of mortality ensues it is hard to emotionally support oneself through to its angelic conclusion. Unlike the great musicologist Tomaszewski, I find little that is 'witty' or 'jocular' in this piece.

The joy and sheer pleasures of the Waltzes in E major (1829) and E minor (1830?) returns us to the youthful life of the ballroom. Sweet nostalgia rather than rough exuberance hovers over the Mazurkas Op.6 (1830-1831) which seems psychologically appropriate after the composer had just left Warsaw. Exuberant rural dance returns in the Mazurka in B flat minor Op.7 No 1 - an Eastern Sarmatian color change emerges on the Erard in the moments of key change and harmonic explorations. Shebanova achieves such expressive dynamic variation and level on the period instrument in Op.7 No 2, one feels is unachievable on a modern grand piano.

The Nocturne Op.9 No 1 in B-flat minor (1830-1831) materializes from silence then sings with the most alluring cantabile, musical phrasing and rubato. On this instrument she achieves a delicate and tender internalized depiction of poignant emotion, especially with the counterpoint and polyphony taken by the left hand. Sometimes the melody barely sounds - Hector Berlioz once referred to Chopin's own immense subtlety of dynamic as if 'elves' were playing on the instrument - silence again.

Berlioz: '....the utmost degree of softness, piano to the extreme, the hammers merely brushing the strings, so much so that one is tempted to go close to the instrument and put one's ear to it as if to a concert of sylphs or elves.' (Quoted in Rink, Sampson Chopin Studies 2 p.51).

In No 2 in E-flat major so familiar and popular a work, Shebanova achieves the unaccustomed nature of a heartfelt, yearning love song rather than simply a fashionable salon piano piece. No.3 in B major is another superb legato song. The agitato that erupts in the middle section of the Nocturne is given an agitated chiaroscuro colour by Shebanova. The song resumes and fades into silence with a pianissimo that is scarcely in existence, a spider web glanced in moonlight.

|

| Landscape with the Good Samaritan (1638) Rembrandt van Rijn |

Finally the Scherzo No.1 in B-minor Op.20 with its turbulent outer sections enclosing the ardent central section, languishing in the reverie of song, another yearning legato of emotional desperation and loss, a cantabile nocturne in its way.

I quote from Tomaszewski which describes better than I can the effect of this work under her fingers : 'When did this piano 'thunderbolt' take place, this record of an explosion of emotion with strength previously unheard of? When was the concept of the song born, which seems to anticipate that Tolstoy's formula, circulated for a well-constructed drama: start fortissimo and then just lead the crescendo to the end? Chopin wrote these measures at the turn of 1830 and 1831 in Vienna, in an aura of overwhelming loneliness, when he made a confession to one of his friends in Warsaw: "If I could, I would move all the tones, what would only blind, furious, furious feeling arouse me ..."? Or a few years later, in Paris, when in white gloves and a brilliant mood , "torn apart in all directions" - as he confided to another of his friends - he entered the first company, because from there, as he wrote, "good taste comes, and you appear to have more talent if the Duchess of Vandemont is supporting you ... ?'

Shebanova gives an unsettling view of intense emotional range, drama and which was surely Chopin's intention - no scherzo 'joke' in evidence in this tormented cry ....

CD 4 – NIFCCD 124

Fryderyk Chopin

Paris (1831–1833)

Ballade in G minor Op. 23 (1835–36)

‘I have received from Chopin a Ballade’, Schumann informed his friend Heinrich Dorn in the autumn of 1836. ‘It seems to me to be the work closest to his genius (though not the most brilliant). I told him that of everything he has created thus far it appeals to my heart the most. After a lengthy silence, Chopin replied with emphasis: “I am glad, because I too like it the best, it is my dearest work”.’

The brilliant Polish musicologist Mieczysław Tomaszewski paints the background to this work best:

'It was during those two years that what was original, individual and distinctive in Chopin spoke through his music with great urgency and violence, expressing the composer’s inner world spontaneously and without constraint – a world of real experiences and traumas, sentimental memories and dreams, romantic notions and fancies. Life did not spare him such experiences and traumas in those years, be it in the sphere of patriotic or of intimate feelings. [...] For everyone, the ballad was an epic work, in which what had been rejected in Classical high poetry now came to the fore: a world of extraordinary, inexplicable, mysterious, fantastical and irrational events inspired by the popular imagination. In Romantic poetry, the ballad became a ‘programmatic’ genre. It was here that the real met the surreal. Mickiewicz gave his own definition: ‘The ballad is a tale spun from the incidents of everyday (that is, real) life or from chivalrous stories, animated by the strangeness of the Romantic world, sung in a melancholy tone, in a serious style, simple and natural in its expressions’. And there is no doubt that in creating the first of his piano ballades, Chopin allowed himself to be inspired by just such a vision of this highly Romantic genre. What he produced was an epic work telling of something that once occurred, ‘animated by strangeness’, suffused with a ‘melancholy tone’, couched in a serious style, expressed in a natural way, and so closer to an instrumental song than to an elaborate aria.'

Shebanova gave us a highly virtuosic, even rhapsodic account of this great work. A scintillating performance certainly but the work only partly emerged as a narrative drama. She allowed the more histrionic, passionate moods to predominate although not without poetic interludes as the 'opera' of this tormented soul unfolded. In this work pianists are often tempted by overly exaggerated contrasts. Two great 'narrative' and individualistic performances of this renowned work are by Shura Cherkassky, Fou Ts'ong and Piotr Paleczny.

|

| La Cité et le Pont Neuf, vus du quai du Louvre by Giuseppe Canella, 1832 |

Etudes Op.10 (1829-1832)

I found it instructive to compare side by side the virtuosic rendition by Shebanova of these Etudes on the Erard with the sound (not the interpretation) of other great virtuosi performing with truly spectacularly bravura on the modern Steinway. From a plethora of choice, I selected Vladimir Ashkenazy on Melodya in 1959 and the rare Maurizio Pollini EMI recording after his Chopin Competition victory, the recording made in 1960. The first noticeable difference is in the balance, timbre, effect of the pedal and colours of the different registers. The bass does not crudely overwhelm the treble of the Erard as it unavoidably tends to do on the massive modern instrument - gymnastically impressive perhaps but limited in aesthetic refinement. The Erard also offers a transparency of sound and articulation that enables Chopin's polyphony, so influenced by Bach, to emerge unsullied and no longer concealed. Of course much of this is a result of Shebanova's art and brilliant pianism, but the period piano enables these musical thoughts and perceptions to reach the listener clear and unclouded.

Op.10 No.1 in C major has a welcome sparkling clarity in its rushing fluidity without 'thumps' of harmonic punctuation in the left hand. In No.2 in A minor, the Erard allows the rich polyphony to emerge with Shebanova. Of No.3 in E major Chopin told his favourite pupil Gutmann that he had never in his life written another such beautiful melody. On one occasion during a lesson on this Etude, Chopin lifted his arms and cried out in desperation O, ma patrie! (Oh, my fatherland!). Shebanova followed this moderate tempo piece with No. 4 in the relative C sharp minor - a tempestuous utterance of passionate energy! The muscular, textured tone quality of the Erard added a special quality to the unbridled nature of this work. We are presented with an impetuous dynamic balance maintained between the two hands, seldom achieved so clearly audible and expressive on the modern instrument. There is a rare sense of desperation in this dialogue.

No.6 in E flat minor (con molto espressione) has a fine cantabile quality of meditative poetry. The unique effect of the pedal (quite different in nature to the modern instrument - it alters the colour and clarity of the sound) was also evident in No.7 in C major. There were occasions however when I felt Shebanova could have penetrated the latent poetry of these studies far more, rather than being irresistibly tempted by a bravura approach. Something I could say of so many great pianists! The young Jan Lisiecki is in possession of inspiring poetry in this regard as of course is Alfred Cortot, always searching for the opium in music, as Daniel Barenboim observed. The concluding bars of No.9 in F minor are magical in the change of colour on this instrument. In No.11 in E flat major one is compellingly reminded of a strummed harp. Sometimes it is the very limitations of the instrument that contribute to the emotional drama and passionate despair of a soul struggling in anger with the paralysis and inability to alter tragic events, to go beyond. This is the case with No.12 in C minor on the Erard. Uniquely unsettling.

One of my favourite sets of Mazurkas are those of Op.17. Tomaszewski writes of No.3: The Mazurka in A flat major is not an easy work. The key to its interpretation would appear to lie in grasping that atmosphere – somewhat surreal, on the boundary of dream and reality. Shebanova gives a most poignant and emotionally touching account of Mazurka No.4 in A minor, an affecting farewell to the recalled dreams of life.

We return to the sheer joys of youth and glamorous Parisian salon life, the mousse of vintage champagne and dance in the exhilarating Waltz in G flat major, Op.71 No.1 with just the shadow of serious thought passing as we briefly gaze into the depths of the glass.

CD 5 – NIFCCD 125

Fryderyk Chopin

Paris (1833–1836)

The French author André Gide was an accomplished pianist and wrote perceptively concerning his passion for Chopin. In his Notes on Chopin (trans. Bernard Frechtman 1949) I find a sentence that applies rather well to Shebanova's approach to this music.

'Chopin proposes, supposes., insinuates, seduces, persuades; he almost never asserts.'

Although awarded 2nd prize in the 10th International Fryderyk Chopin Competition in 1980 (won by Dang Thai Son), Shebanova does not play with a concern for display or grandstanding virtuosity which would elicit sharp intakes of breath by the audience. She feels the ambiance of a 19th century drawing room and the need to convey to a listening audience the intimate thoughts of Chopin. Naturally she has the technique in reserve if required to dazzle in style brillant but clearly wants listeners to be moved rather than astonished.

The programme of this disc has

been carefully and musically assembled. The opening Nocturne in F

major Op.15 No.1 of this set (1830-1833) transports us into that

extraordinary dream nightscape painted by Chopin and so

characteristically and profoundly his own. He raised the genre far beyond the

truism of comparison or even inspiration by John Field. This oft quoted

connection seems rather superficial to me. In the F major a meditative,

internalized idyllic thought is suddenly interrupted by a storm of

disaffection and Polish żal, a disconcerting angry

agitation which subsides back into resigned illusions and the music of the

opening. The beautiful singing melody suits Shebanova well. The con

fuoco central section, a harsh volcano in F minor, appears a

dramatic contrast on the Erard - of texture, timbre

and colour, inimitable on a Steinway.

One of the finest penetrations of

the complex, ambiguous and indeterminate soul of Chopin occurs in her

sensitive account of the unfathomable mysteries of the Nocturne

in G minor Op.15 No.3. Surely an emotional highlight of this CD.

Her expressive intention is perfectly complemented by the fragility,

colour and tone quality of the period instrument. Marcel Antoni Szulc wrote of

the reaction of early listeners to this Nocturne:

‘They vouch that on the day

after attending the theatre for a performance of Hamlet, Chopin wrote the Nocturne,

Op. 15 No. 3 and gave it the inscription 'at the cemetery'. But when it

was to go to print, he expunged the inscription, declaring 'let them

guess.’

Whatever the truth of the matter

(there is controversy here). André Gide again:

'We are told that when he was

at the piano Chopin always looked as if he were improvising; that is, he seemed

to be constantly seeking, inventing, discovering his thought little by

little.’ For me this certainly applies in this indecisive,

questioning piece, searching among its inconclusive harmonies for a

modicum of ultimately inaccessible certainty in the face of death.

There is an imaginative and

moving key connection with the piece that follows, the Mazurka No.1 in

G minor Op. 24. Here another aspect of Shebanova's playing is brought

to the fore, her understated and moderate tempi for this entire set of

mazurkas. An alternative poetic musical meaning emerges at her tempo which

is sometimes lost in the often more rumbustious, folkloric Polish approach

to this genre. However, one argues truly at one's peril in Poland

concerning the dark art of the 'correct' interpretation of a Chopin

mazurka.

Gide observes the courage

required to play more slowly than is customary. He believed, not in the

excessive slowing down of tempi, but 'allowing it its natural movement,

easy as breathing.' He quotes lines from the great French poet

Paul Valéry:

Est-il art plus tendre

Que cette lenteur

[Is there art more gentle

Than this

slowness?]

The concluding bars of the Mazurka in B flat minor is beyond compare on this instrument in its expression of an acute sensibility.

We are then presented with another face of Frederyk Chopin, a highly entertaining and joyful rendition of a youthful work seldom heard in concert, the Variations brillantes in B-flat major on 'Je vends des scapulaires' ['I sell scapulars'] Op.12 (1833) This work is from the popular two act comic opera Ludovic begun by Ferdinand Hérold and completed by Fromental Halévy with a libretto by Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges (1833). Chopin loved opera, was a consummate actor and mimic, a practical joker, humorist and all-round great fellow as a young man. Such qualities are reflected here.

Two mazurkas No. 1 and No. 3 from Op.67 (1835) follow, a Mazurka in C major Op.Posth. No.57 (1825? or 1833?) which I had never heard before.

On then to another happy dance piece, one of my favourite lighter Chopin works, performed in piano competitions but seldom in recital, the Boléro Op.19 (1833). The boléro was originally a lively and rather sensual Spanish dance in triple metre originating in the 18th century and popular in the 19th. The apparent inspiration for this Boléro was Chopin's friendship with the French soprano Pauline Viardot, whose father, the renowned Spanish tenor Manuel Garcia, had introduced boléros to Paris. It is rather a Polonized Spanish work in essence but full of energy and spicy rhythms, even termed by one observer a boléro à la polonaise.

Shebanova gave a stylish and spirited performance of this rarely performed in recital but rhythmically exciting and youthful work of Chopin. One of the best performances I have ever heard was by Nikolay Khozyainov, the youngest finalist of the XVI International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in October 2010. The Polish pianist Piotr Banasik also has a uniquely 'Latin/Polish' feel for this remarkable work. I cannot help reflecting on Julian Fontana, Chopin's much put upon amanuensis, visiting Cuba in 1844 where he wrote in 1847 the idiomatic Souvenirs de I’le de Cuba Op. 12. With Shebanova, although a fine interpretation, I felt I wanted more sensual 'clipping' of the rhythmic figures - more garlic if you wish, which could not possibly have been Chopin's intention!

|

| A Bolero Dancer by Antonio Cabral Bejarano (1788-1861) |

The charming Waltz in A flat major Op.69 No.1 (1835) also known as 'Adieux' was published posthumously and initially inscribed in the album of his beloved Maria Wodzińska in haste just before he left Dresden.

She wrote to him in Paris '[...] On Saturday, when you left us, we all walked in sadness, our eyes filled with tears since your departure [...] you have been the subject of all our conversations. Feliks kept asking me for the Waltz ) the last thing we received and which we heard you play. We took great pleasure in it: they in the listening, and I in the playing [...] I've taken it to be bound [...]' After the relationship foundered, the waltz was presented to two other pupils of Chopin.

(From a letter sent by Maria Wodzińska to Chopin in Paris, Dresden September 1835)

'Apparently, Fryderyk wrote for Maria some waltz in her album, may she preserve it like a relic and allow no-one to copy it, that it may not lose its lustre.'

(From a letter sent by Antoni Wodziński to Teresa Wodzińska in Sluzew, Paris October 1835)

Shebanova played the work with great charm but with a curious unmarked accelerando in the Trio which did little to enhance the expression of 'farewell'. There was a fine although not individual performance of the Fantaisie Impromptu in C-sharp minor Op. 66 (1834).

Then to conclude two Polonaises Op.26 (1831-1836). These certainly indicated a change of ambiance from his previous alluring 'salon polonaises'. They have been transformed into an heroic, impassioned nationalist statement of musical defiance and anguish. Anton Rubinstein felt a chasm yawned between these two periods of composition within the same genre. Both polonaises contain lyrical and dramatic elements in severe contrast. The first, again in the key of C sharp minor, has a central episode of almost insupportable tragic poetry, an anguished cantabile. I felt Shebanova could have made far more of this emotional contrast by lingering over this poignant deeply affecting melody, even if verging on sentiment. She was far more successful in the second in E flat minor which was more expressive onwards from the gloomy, ominous opening, so full of foreboding. The unfocused tone quality and colour of the Erard in this register contributed greatly to this overall feeling of loss. The Trio augmented the darkness and despair in a work of unsurpassed melancholy and despondency.

|

| November Uprising 1830-1831 Janvier Suchodolski |

CD 6 – NIFCCD 126

Fryderyk Chopin

Paris (1835–1837)

The major

works on this disc are the Op.25 Etudes (before 1837)

Originally

Chopin dedicated the work to Franz Liszt. The change of dedication to Marie

d'Agoult is a rather entertaining anecdote. It is alleged that Liszt was

romantically involved with Marie Pleyel, then the beautiful wife of

Chopin's friend and colleague Camille Pleyel. It appears Liszt used Chopin's

rooms in Paris at rue de la Chaussée d'Antin for a tryst that the

German musical scholar Frederick Niecks described euphemistically: The

circumstances are of too delicate a nature to be set forth in detail. The

discovery of traces of the use to which his rooms had been put justly enraged

Chopin. ('Frederick Chopin as Man and Musician' vol.2

p.171). Moreover, the insult was compounded commercially as business

competitors. Liszt represented Erard pianos whilst Chopin

the Pleyel. The friendship did not fully recover.

More

seriously, the unique feeling one obtains from these familiar and

ultimately challenging keyboard pieces on the Erard is

remarkable. Most listeners will be familiar with the fact that the

etudes of Cramer and Moscheles influenced the Op.10 Etudes of

Chopin. However, the Vingt Exercises et Préludes (1820) by

Maria Szymanowska and the famous Etudes Op.20 (1825)

by Chopin's friend Joseph Christoph Kessler, should not be forgotten.

These musicians had significant influence in Warsaw musical circles

when Chopin was composing these works.

On the Erard the

different colours, timbres and textures of the registers, the unique

effect of the pedals on the sound together with Shebanov's sensitive

expressiveness bathe these studies in an unaccustomed light. This

redefinition elevates the works out of the viruoso-obsessed, rather

homogenized Steinway sound they are subjected to far too often.

The Mazurkas Op.

30 (1835-1837) are delightful miniatures. The poet Kornel Ujejski, who

wrote what he called ‘translations’ of Chopin, lent No. 2, the B minor

Mazurka, a sentimental anecdote. The cuckoo tells a girl when she will

wed: ‘Ile więc razy kukułeczka kuknie, /To za wiosen tyle wezmę ślubną

suknię’ [So however many times the little cuckoo sings, /You’ll don

your wedding dress in that many springs]. The Nocturnes Op.32

have an unsettling shift of mood from the blithe to

dark premonitions, from the elegiac to the impassioned.

Shebanova

brings a feeling of carefree, improvised joy to the Impromptu in A flat

major Op.29 (1837). The Scherzo in B flat minor Op.31

(1835-1837) is a marvelously dramatic interpretation with an

authentic feeling of narrative and complex swings of mood and

heightened emotion coupled with poetic meditation. The Erard adds

significantly to these chiaroscuro contrasts of colour.

CD 7 – NIFCCD 127

Fryderyk Chopin

Paris, Majorca (1837–1839)

Hardly anyone playing Chopin waltzes (or even mazurkas) has any idea of ballroom dancing in the nineteenth century. Chopin in his youth was mad about dancing, a fine dancer and also an excellent dance pianist playing into the small hours, hence his need for 'rehab' at Bad Reinherz – now Dusznki Zdrój. Certainly Chopin waltzes are not meant to be danced but the sublimated idiom remains. All young pianists should be encouraged to take dancing lessons! These waltzes show that Shebanova almost achieves the charm, rhythm and stylish panache that the Chopin waltz requires but is rarely obtained from pianists (Op.34 Nos. 1 & 3 before 1838).

The set of four Mazurkas Op.23 (1836-1838) opens and ends in an affecting minor keys with a certain joyfulness in the central two works. A strong feeling of nostalgia opens and closes this set as if the moods of the composer fluctuate from recollection of pleasure to the darker, more melancholic realities of exile. The tone of the Erard communicates these emotional moods in a way that borders on the extra-sensual.

The popularity of the Polonaise No.1 in A major (known as 'the Military') rather overshadows the introverted anger and dark travails of Polonaise No.2 in C minor. This is one of the most impressive works recorded in this collection by Shebanova on the Erard. The texture and timbre of this register Chopin utilizes with his acute ear bathes the opening in shifting adumbral light that scarcely ever brightens into true lyricism, although it struggles. The darkness intensifies in fact as we progress through the piece, expressively loaded with deepest anger and resentment.

Shebanova paints her interpretation in dark planes of existential unease and disinheritance. I find no humour here in the emotional rubato or dynamic variation despite other commentaries assuring me it is present and is in fact an ironical work. A magnificent gesture of resistance in her account of this polonaise with an inspired moment of resignation at the close.

Préludes (1831? - 1839)

Everyone knows the Préludes pour le piano

Op.28 were written and completed in Majorca where Chopin resided at first in

Palma where 'The sky is like turquoise, the sea like azure, the mountains

like emerald, the air like heaven [...] guitars and singing for hours on end. [Letter

to Julian Fontana in Paris from Palma, 15 November 1838]. But by 3rd December,

again to Fontana, 'I was sick like a dog for the last two weeks : I caught

cold in spite of 18 degrees temperatures, roses, oranges, palms and fig trees. Work

on the Préludes was inevitably

delayed.

Later, a few miles distant from Palma, Chopin

wrote from a Carthusian Monastery in Valldemossa, experiencing extreme

fluctuation of mood, (where he stayed from 15th December 1838 until 11 February

1839):'The cell has the shape of a tall coffin. [...] Next to the bed is an

old untouchable square piece of junk, which is hardly serviceable for my

writing, on it a leaden candlestick (a great luxury here) with a candle.

Bach, my scribblings and other people's scraps of paper ... quiet ...one could

scream ... still quiet. In a word I am writing to you from a strange place.[Letter

to Fontana in Paris, postmarked Palma, 28 December 1838]

Music scholarship has long connected these Préludes

structurally in design with Bach's 48 Preludes and Fugues of Das wohltemperierte Klavier. Chopin

performed this Bach masterpiece, corrected printing mistakes, used them as

teaching material and was deeply influenced by the composer. The connection is

acutely symmetrical, more than most realise. [Symmetry and Template: Bach's

Well-Tempered Clavier, and Chopin's Preludes, Op.28 - Ruth Tatlow in Bach

and Chopin NIFC 2020]

It would, of course, have been impossible for Chopin

to have ever considered performing this complete radical cycle in his musical

and cultural ambiance (not least because of the brevity of many of the pieces).

Although it is now well established as a complete work, a masterpiece of

integrated ‘fragments’ (in the nineteenth century sense of that aesthetic

term). Each can of course stand on its own as a perfect miniature landscape of

feeling and tonal climate but ‘Why Preludes? Preludes to what?’ as André

Gide asked. I think it unnecessary and superfluous to actually answer this

question. We must to turn to Chopin’s love of Bach to at least partially

understand them. I think it was Anton Rubinstein who first performed them as a

cycle but I stand to be corrected on this.

Some performers of the cycle (Grigory Sokolov, Martha

Argerich, Dimitry Ablogin and the greatest historically to my mind by Alfred

Cortot) give one the impression of an integrated 'philosophy' or spiritual

narrative. Shebanova achieves a similar life destiny unfolding. As always, I

felt the magnificent bass resonance in the left hand of many of the Preludes on

the Steinway occasionally unbalances the musical writing. This is absent on the

Erard. The Preludes were

written in a period of great emotional upheaval for Chopin. Some of their

'Prelude egos' are often inflated by the instrument itself, etiolating the

emotional panorama rather than retaining the intimacy which waxes and wanes so

fleetingly and poetically.

I cannot possibly give an account of each

prelude nor would it be desirable in review of this nature. I choose some representatives.

The registers on an Erard are not homogenized as is the ideal of the Steinway design. The sound colour of the Erard gives a feeling to No 2 in A minor of the fragility of human life in the face of the heavy tread of the inevitable approach of the 'great reaper'. In No. 6 in B minor the cantabile left hand sings smoothly and effortlessly in a different colour and timbre to the right and on the Erard. Gentle and fragile nostalgic memory of ballroom emotions suffuse No.7 in A major.

The articulation Shebanova brings to No. 8 in F sharp minor creates the image of a huge flock of water birds suddenly rising, disturbed and anxious, from the surface of a still lake in the forest. The colour palette contrast between the mahogany introspective heaviness of No.9 in E major and the brief, lace-like flutter of fragility of No.10 in C sharp minor in the delicate upper register on this instrument has such aesthetic beauty. The dark coloured, almost rough neurotic agitation, so clear on the Erard of N0.14 in E flat minor is in such stark contrast to the beautiful cantilena contained within No.13 in F sharp minor and the almost over-familiar No 15 in D flat major. I felt Shebaova could have sounded more 'haunted' by time in this work - the repeated so-called 'raindrops' are far more fatalistic than many pianists realize.

But at my back I always hear

Time's winged chariot hurrying near

[From To his coy mistress Andrew Marvell (1621-1678)]

On this instrument, the very construction limits the forte that is physically possible which gives a completely different dynamic range and limit that the pianist must work within to sound mellifluous. It is estimated that Chopin played at a full dynamic step lower than that we are accustomed to.

No.16 in B flat minor has a fine dramatic balance between the 'limping' LH and 'running' RH rarely achieved on the Steinway and an exciting tactile feeling to the Presto con fuoco articulation. In No.17 in A flat major Shebanova makes the forzando ![]() symbol on the repeated bottom A flat from Bars 65-90 (conclusion of the piece) uniquely expressive and fatalistic on this instrument to sound like, as Chopin indicated '....the idea of that Prelude is based on the sound of an old clock in the castle which strikes the eleventh hour' [Paderewski Memoirs, London 1939] The eleventh hour in life - the last moment or almost too late. From the agitation of No.22 in G minor, the blithe No.23 in F major to finally the passionate utterance of No. 24 in D

minor, traditionally the 'key of death'. The last three notes (the

lowest D on the piano) Shebanova gave expression to the lines by the

Welsh poet Dylan Thomas in his poem Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good

Night which could apply to the spirit of the Chopin Préludes pour le piano cycle as a whole:

symbol on the repeated bottom A flat from Bars 65-90 (conclusion of the piece) uniquely expressive and fatalistic on this instrument to sound like, as Chopin indicated '....the idea of that Prelude is based on the sound of an old clock in the castle which strikes the eleventh hour' [Paderewski Memoirs, London 1939] The eleventh hour in life - the last moment or almost too late. From the agitation of No.22 in G minor, the blithe No.23 in F major to finally the passionate utterance of No. 24 in D

minor, traditionally the 'key of death'. The last three notes (the

lowest D on the piano) Shebanova gave expression to the lines by the

Welsh poet Dylan Thomas in his poem Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good

Night which could apply to the spirit of the Chopin Préludes pour le piano cycle as a whole:

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding

sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

A fine account of the Préludes with some splendid moments of emotional density unachievable on a modern instrument, however fine the pianist.

CD 8 – NIFCCD 128

Fryderyk Chopin

Majorca, Nohant (1838–1839)

Ballade in F major Op.38 (1839)

Penetrating the expressive core of the Chopin Ballades requires an understanding of the influence of a generalized view of the literary, musical and operatic balladic genres of the time. In the structure there are parallels with sonata form but Chopin basically invented an entirely new musical material, nothing less than a new genre. I have always felt it helpful to consider the Chopin Ballades as miniature operas being played out in absolute music, forever exercising one's musical imagination.

Chopin was working on the F major Ballade in Majorca. In January 1839, after his Pleyel pianino had arrived from Paris, he wrote to Fontana ‘You’ll soon receive the Preludes and the Ballade’. And a few days after, when sending the manuscript of the Preludes: ‘In a couple of weeks, you’ll receive the Ballade, Polonaises and Scherzo.' So the conception took place in the atmosphere of a haunted monastery, threatened by untamed nature. The same ambiance as the Preludes. Here was conceived the idea of contrasting a gentle and melodic siciliana with a demonic presto con fuoco – the music of those ‘impassioned episodes’, as Schumann referred to them.

The Leipzig encounter with Chopin Schumann experienced in 1840 is instructive. 'A new Chopin Ballade has appeared’, he noted in his diary. ‘It is dedicated to me and gives me greater joy than if I’d received an order from some ruler’. He remembered a conversation with Chopin: ‘At that time he also mentioned that certain poems of Mickiewicz had suggested his ballade to him.’ So the narrative balladic tradition did underlie this conception but naturally not in any programmatic way.

In the opinion of the musicologist and Chopinist Jim Samson, the work can only be explained as a two key piece, in both F major and A minor, yet coalesces into an entire organic expression, a Romantic 'fragment of autobiography' if you will. Sometimes Chopin would perform the childlike innocence of the opening lyrical siciliana as a separate work and not continue to the volcanic, explosive and almost terrifyingly passionate presto con fuoco. The regions of the work loosely resemble in spirit and design, that of the Preludes themselves, almost bordering on the autonomous.

Shebanova makes much of the contrast of mood and the chiaroscuro illumination of this highly temperamental, febrile fluctuation in the work, much assisted by the disturbing varied register colours and timbres given these moods on the Erard. The driving desperation she brings before the exhausted resignation of the close is deeply affecting. Certainly she presented 'Op. 38 as a narrative of national martyrdom'. [Professor Johnathan D. Bellman]

I have always felt piano students during the course of their studies should be urged by their teachers to play some Chopin on an early instrument to augment their feeling and cultural contextual understanding of what his pupil Princess Marcelina Czartoryska referred to as 'le climat de Chopin'. Accelerate their imagination! Chopin was that breed, a composer-pianist, exclusively playing his own work in recital. What a transcendent experience that must have been on a Pleyel or if he was physically tired, an Erard.

Mazurkas Op.41 (1838-1839)

A sketch of this mazurka was made at Son Vent on Majorca, shortly after Chopin and Sand arrived on the island, hence the name ‘Palman’ given to No.1 the Mazurka in E minor. Along with three others, composed slightly later, the ‘Palman’ Mazurka was published the year after Chopin’s return from Majorca.

That great Polish authority on the composer, Mieczyslaw Tomaszewski, informs us that within the work we hear a distinct Polish echo: the melody of a song about an uhlan and his girl, ‘Tam na błoniu błyszczy kwiecie’ [Flowers sparkling on the common] (written by Count Wenzel Gallenberg, with words by Franciszek Kowalski) – a song that during the insurrection in Poland had been among the most popular. Chopin quoted it almost literally, at the same time heightening the drama, giving it a nostalgic, and ultimately all but tragic, tone.

The remainder were full of simple nostalgia and tender melodies so suited to Shebanova and this instrument.

Scherzo in C-sharp minor Op.39 (1839)

Chopin

completed this work during a period of convalescence in Marseilles. It is 'one

of Chopin's most unusual and original works' (Jim Samson). Certainly

it is the closest Chopin came to the Lisztian idiom and in the bravura writing.

The piece was dedicated to his muscular favourite pupil Adolf Gutman. Wilhelm

von Lenz wrote rather waspishly in 1872 '... it was probably with his

prize-fighter's fist in mind that the bass chord was thought out, a chord that

no left hand can take (sixth

measure, d sharp, f sharp, g, d sharp, f sharp),

least of all Chopin’s hand, which arpeggio’d over the easy-running,

narrow-keyed Pleyel. Only Gutmann could 'knock a hole in a table'

with that chord!’

The close was a triumph of the spirit over adversity. Almost Lisztian grandeur was summoned in her powerful and dramatic transition from C-sharp minor to the victorious C-sharp major conclusion.

|

A computer version of the figure of Fryderyk Chopin, which was created, among others based on two photos and a tuft of hair from the Warsaw museum by Hadi Karim

The two Nocturnes Op. 37 (1839) date from the time of Chopin’s period on Majorca.

The first in G minor was written before that romantic adventure. The G major not long after. Do I imagine the mood of the first reflects romantic optimism and the second a degree of cogent realism? Shebanova renders the tender 'chorale' region superbly with the pedal on the Erard as the slightly inefficient damping gives a background wash of sound which softens the chordal effects. Some period commentators have associated the music of these bars with ‘a prayer played on a country organ’. The choir falls silent before the nostalgic, even elegiac cantabile melody returns. The pianissimo entry is deeply moving. The ultimate conclusion of the nocturne in the major at a pianissimo unachievable on a Steinway, dematerializes into the ether of the night, the velvet wings of a moth...

Sonata in B-flat minor Op.35 (1839)

| |

Cztery struny skrzypiec [Four Strings of a Violin] 1914

|

The great Polish musicologist Tomaszewski describes the opening movement of this sonata Grave. Doppio movimento perceptively: ‘The Sonata was written in the atmosphere of a passion newly manifest, but frozen by the threat of death.’ A deep existential dilemma for Chopin speaks from these pages written in Nohant in 1839. The pianist, like all of us, must go one dimension deeper to plumb the terrifying abyss this sonata opens at our feet. This I felt Shebanova accomplished in a particularly haunting way, possessed a degree of tragedy and menace. The left hand halting, almost wounded rhythm, became such an important emotional counterpoint on the Erard. I never felt any empty display of egocentric virtuosity which is all too often prominent. Shebanova on this instrument became a conduit for the inspiration, a pure channelling of the composer beyond her personality. Her phrasing breathed musically, the polyphony transparent and clear, the rubato often deeply affecting. An introspective and deeply angry discontent with the nature of mortality emerges from her reading.

The Scherzo again put me in mind of Tomaszewski who commented: ‘…one might say that it combines Beethovenian vigour with the wildness of Goya’s Caprichos.' The beautiful cantabile Trio took us singing into the further dimension of ardent dreams which makes the Marche funèbre such a shocking emotional jolt of the force of destiny. The dark colour of the Erard register where Chopin sets this theme gives an immediate atmosphere of tragedy to the Marche funèbre. The tempo is slow, deliberate yet not heavy as the pall bearers proceed, swaying through the cemetery to the funeral plot. This is not an imaginary military band with a heavy dull tread lacking in poetry.

The reflective Trio was sensitively presented by Shebanova as a contrast of innocence, love and purity blighted by the reality of death (Chopin was terrified of being buried alive – often horrifyingly possible in those primitive medical times). In the fragile upper register of the Erard it truly sang as an aria, replete with profoundly despairing nostalgia for the blithe past (this gloriously soaring aria would be next to impossible to spoil if sensitively played on any piano. The innocence was immensely heightened here - it remains sublime Chopin). The fragility of life and the ruthless pendulum of fate and death needs to be feelingly communicated to us, as was done. The scale of the dynamic of the return of the Marche cannot ever become overblown and crudely prosaic on the Erard as it too often is on a Steinway, bearing in mind the 'limited' dynamic ceiling and nature of the early instrument.

The Presto did not erupt in a virtuoso style yet the baroque counterpoint, polyphony and harmonic complexities were clearly indicated to my rather Gothic imagination. The disturbing grief of an unhinged mind, the wind blowing autumn leaves over the grave or more simply the reverential remembrances in sotto voce conversation...

CD 9 – NIFCCD 129

Fryderyk Chopin

Paris, Nohant (1840–1841)

|

| The George Sand mansion, Nohant |

However, the divine, somnambulist melody of the Nocturne Op.48 No.1 in C minor (composed at Nohant) flowered lento and sotto voce in a captivating way on the soft-toned Erard. In lessons Chopin was extremely exacting in the manner in which he wanted this opening executed. Shebanova is unsurpassed in the emotional delicacy of her touch in painting this nocturne as it evolves into the meditative chorale, growing in strength through broken chords like a flurry of windswept rain, an expression of heightened yet febrile emotion. The layered texture of the Erard sound adds to this rich effect. This nocturne is nothing less than an emotive metamorphosis from internal personal spiritual reflection to external majesty - a soundscape of an emotional life.

The writer and

musicographer Ferdynand Hoesick (1867-1941) described the

performance by Ignacy Jan Paderewski as elevating this nocturne to

the status of the 'heroic', a paradigm of grief. Emotional turbulence

fades back into the poetry of a scarcely perceptible pianissimo, a return

to the silence from which piece emerged. This perfectly structured and

nuanced performance is surely one of the greatest expressive

moments of this entire collection.

One might regard Marcel Proust as

appropriate to quote here. From Swann's Way:

She [Mme. de Cambremer] had been taught in

her girlhood to fondle and cherish those long-necked, sinuous creatures, the

phrases of Chopin, so free, so flexible, so tactile, which begin by seeking

their ultimate resting-place somewhere beyond and far wide of the direction in

which they started, the point which one might have expected them to reach,

phrases which divert themselves in those fantastic bypaths only to return more

deliberately—with a more premediated reaction, with more precision, as on a

crystal bowl which, if you strike it, will ring and throb until you cry aloud

in anguish—to clutch at one’s heart.

|

| Chopin's former room at Nohant - only the entrance doors are original |

Georges Sand

complained of Chopin to Marie de Rozières during the composition of this

polonaise during a summer at Nohant:

‘Two days

ago, he said not a word to anyone the whole day. Has someone angered him? Did I

say something to worry him?’ In a letter to Doctor Gaubert, her account was

more colourful: ‘Chopin’s up to his usual tricks, fuming at his piano. When his

mount fails to respond to his intentions, he deals it great blows with his

fist, such that the poor piano simply groans. […] he considers himself idle

because he’s not crushed by work’.

Liszt

commented on the energetic rhythms of Chopin Polonaises that they ‘thrill

and galvanise the torpor of our indifference’.

Such a magnificent polonaise! This masterpiece of musical structure and emotion, this pianistically demanding keyboard work, for me the greatest of his polonaises, was penetratingly interpreted by Shebanova. What emotional landscapes we cover here and valleys of psychological turmoil. This is a fine, passionate and noble performance of heroic defiance. On the Steinway, the work can often appear heavy and grossly unsubtle, but on the Erard the temptations of dynamic inflation are gratefully denied by the physical limitations of the instrument itself.

The 'military' heartlessness and dynamic of the repetitive, insistent, even merciless bars of the seemingly endless groups of thirty-second notes (demisemiquavers) are clear emotionally on the Erard, never sounding like an anvil crushing the skull as they too often do in the wrong hands on the modern instrument. Shebanova brings just the right adjustment of expressiveness to her conception of the work, especially in the embedded Doppio movimento (Tempo di Mazurka). The tender lyricism of nostalgia slowly begins to evolve into what one might describe as resentful nostalgia until the polonaise returns with the vengeance of fortissimo octave runs to the very upper limits of the period keyboard. I am reminded of a description Liszt wrote of Chopin's conception of the unique Polish emotion of żal:

'Żal!

Strange substantive, embracing a strange diversity, a strange philosophy!

Susceptible of different regimens, it includes all the tenderness, all the

humility of a regret borne with resignation and without a murmur, while bowing

before the fiat of necessity, the inscrutable decrees of Providence: but,

changing its character, and assuming the regimen indirect as soon as it is

addressed to man, it signifies excitement, agitation, rancor, revolt full of

reproach, premeditated vengeance, menace never ceasing to threaten if

retaliation should become possible, feeding itself, meanwhile with a bitter, if

sterile, hatred.'

The disc also

contains some interesting rarely heard pieces. The Fugue in A

minor (1827 0r 1841). Chopin adored of Bach and polyphony. We are told

by his pupil von Lenz that before one of his rare concerts, Chopin, a

composer-pianist, would lock himself away and play not his own work but

only Das

wohltemperierte Klavier for

two weeks. Also there is the song Spring arranged by the

composer for piano solo.

I feel

Shebanova does not share my joyful sense of the waltzes (there are three more

on this disc) or the latin warmth of the Italianate Tarantella or

Hiberian Bolero. The joy, affectation, sprung rhythms, panache

and Parisian or Viennese esprit of the waltzes seems to

escape these otherwise fine performances. We all have our own Chopin of course,

the source of the greatness of this composer!

Fantasy in F minor Op.49 (1841)

In a letter to Julian Fontata in

October 1841 Chopin wrote: ‘Today I finished the Fantasy – and the sky is

beautiful, there’s a sadness in my heart – but that’s alright. If it were

otherwise, perhaps my existence would be worth nothing to anyone’.

Many regard this intensely

patriotic work as one of the greatest musical achievements of Chopin. The

difficulties in bringing together the fragmented nature of the Fantasy

in F Minor Op. 49 are well known. Carl Czerny wrote perceptively in

his introduction to the art of improvisation on the piano 'If a well-written

composition can be compared with a noble architectural edifice in which

symmetry must predominate, then a fantasy well done is akin to a beautiful

English garden, seemingly irregular, but full of surprising variety, and

executed rationally, meaningfully, and according to plan.'

At the time Chopin wrote this work improvisation in public domain was

declining. With many of Chopin's apparently 'discontinuous' works (say

the Polonaise-Fantaisie) there is in fact an underlying and

complexly wrought tonal structure that holds these wonderful dreams of his

tightly together as rational wholes. Shebanova accomplished this difficult cohesive

task magnificently.

C.P.E Bach wrote extended single movements as a freie Fantasie [‘free fantasy’] in his renowned empfindsamer Stil (‘sensitive style’), his theory of ‘effects’ or Empfindungen, works that betray a rather turbulent range of mood and expression. I have written before of his influence on Chopin's teachers in Warsaw and in his own compositions and also that of Maria Szymanowska (who herself wrote in 1819 a Fantasy in F minor, a Fantaisie dédiée à son altesse Madame la Princesse Zajączek. Being a harpsichordist and playing a Pleyel myself, I felt the transfer to the Erard piano emphasised the striking effects, colours, timbres and emotions possible on the earlier instruments. Shebanova made full use of these all these extraordinary emotive contrasts.

The great German philosopher and

musicologist Theodor W. Adorno wrote: ‘A listener must stop up his ears not

to hear Chopin’s F Minor Fantasy as a kind of tragically decorative song of

triumph to the effect that Poland was not lost forever, that some day […] she

would rise again.’

Poles can ascertain musical connections and allusions to insurrectionist songs that remain concealed to foreigners such as myself. I allow the far more perceptive Polish musicologist Tomaszewski to speak:

'The Fantasy was composed on motives from one of the most popular Polish insurrectionary songs, namely ‘Litwinka’ by Karol Kurpiński. ‘Litwinka’ was sung by the whole of Poland and the whole of the Great Emigration – the community of exiles who fled Poland in the wake of the November Uprising. It was included in songbooks: for example, in Pieśni Rewolucji Polskiej z 29 listopada roku 1830 [Songs of the Polish revolution of 29 November 1830], published in Paris in 1832 by Wojciech Sowiński and in an analogous collection published in Leipzig the following year by Feliks Biliński. Richard Wagner included a couple of phrases from this song in his overture Polonia.

Familiar national allusions and memories fill the work. From his earliest compositions and youth under the brutal Russian hegemony, Chopin had been drawn to patriotic allusions and improvisations on national themes. There is a true improvisatory feel to this writing which Shebanova was clearly aware of and utilized from the opening of the Fantasy. The even-paced bass allusively evokes the insurrectionist song: ‘Bracia, do bitwy nadszedł czas’ ['Brothers, the time has come to battle']. Even a chorale appears, in the most distant key from F minor: B major. This is like a voice ‘from another world’. This chorale interlude has been called a ‘hymn’, a ‘prayer’, a ‘song of ardent faith’ and an ‘epiphanic’ moment. Shebanova musicianship and acute ear is able to make much of this mercurial shifting of mood and spiritual aspiration on the Erard. In our secular day it is easy to forget that Chopin was from a deeply religious family and had clearly a deep vein of religiosity running through his spirit like an occasionally broken Ariadne's thread. Yet despite this display of genius, the Fantasy was received with confusion as a ‘series of bewildering images’.

As I listened to this great revolutionary statement, fierce anger, nostalgia for past joys and plea for freedom, I could not help reflecting how the artistic expression of the powerful spirit of resistance in much of Chopin is so desperately needed today - not only in the restricted nationalistic Polish spirit he envisioned but with the powerful arm of his universality of soul, confronted as we are throughout the world by incomprehensible onslaughts of evil, barbarism, self-serving politics and now a profoundly tragic plague. We need Chopin, his heart and spiritual force in 2021 possibly more than ever.

Ballade in A flat Major Op.47 (1841)

|

| A Scene from ‘Undine’ (1843) Daniel Maclise (1806–1870) The Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, Windsor, England. |

Shebanova completes this recording with an impassioned performance of the third Ballade Op. 47. Penetrating the expressive core of the Chopin Ballades requires an understanding of the influence of a generalized view of the literary, musical and operatic balladic genres of the time. His Ballades certainly have a nationalist Polish spirit but far wider European cultural musical reference which gives them such deep universality. Dramatic musical poems without words yet the 'story' would be familiar and coherent emotionally. It is not merely a virtuoso piece but has significantly deep musical and ‘balladic meaning’ in a sense that was familiar to educated people of those days but we have lost almost entirely.

In the structure there are parallels with sonata form but Chopin basically invented entirely new musical material and narrative. This music must be felt to grow organically and powerfully from within the impassioned shifts of mood of the composer’s heart and spirit as well as maintaining its dramatic narrative flow.

I have always felt it helpful to consider the Chopin Ballades as miniature operas being played out in absolute music, forever exercising one's musical imagination. The work contains some of the most magical passages in Chopin, some of the greatest moments of passionate fervour culminating in other periods of shattering climatic tension.

The Ballades reflect the fluctuating 'moving toy-shop of the heart' [Alexander Pope]. Again composed at Nohant this radiant Ballade fluctuates in its moods and emotional scope and of course has attracted many suppositions of a programmatic content despite Chopin's intense dislike of this idea applied to his music. Schumann wrote of the ‘breath of poetry’ breathing from this great work. The German violinist and critic Friedrich Niecks heard in the Ballade ‘a quiver of excitement’. ‘Insinuation and persuasion cannot be more irresistible, grace and affection more seductive.’ he wrote. For the Polish pedagogue and pianist Jan Kleczynski, it is ‘evidently inspired by [Adam Mickiewicz’s tale of] Undine. A supremely romantic inspiration flows like a country stream through beds of summer wild-flowers.'

Shebanova gives a penetrating, Romantic performance on this Erard, its shifting colours so suitable to depict mercurial moods. She balances Chopin's masculine strength and feminine sensibility - so characteristic of his music.

At Nohant...

CD 10 – NIFCCD 130

Fryderyk Chopin

Last period (1833-1842)

Allegro de concert in A major Op.46 (1832-1841)

Shebanova makes a style brillant piece from this rarely performed work. Chopin said of it 'This is the first piece I shall play in my first concert on returning home to a free Warsaw.' There is much speculation that it was perhaps the first movement of a third concerto. Certainly the piano writing begs for orchestral interludes and detail. I have always felt a stylistic struggle in the writing (Chopin began it in 1831) but did not finish the work after some hesitations until at least 1841. A fascinating transitional work of metamorphosis from youthful glitter to expression of passionate patriotic resistance. It deserves more exposure certainly.

Scherzo in E major Op.54 (1842)

Shebanova gave a fine performance of this comparatively rarely performed work. This scherzo is not dramatic in the demonic sense of the three previous scherzi, but lighter in ambiance which suited the Erard upper registers particularly well. It is a composition of great contrasts. The outer sections are a strange exercise in rather joke-filled fun with a darkly concealed centre of passionate grotesquerie. The work mysteriously encloses a deeply felt and ardent nocturne in the form of a longing love poem, suffused with a sense of loss. Shebanova used the register colours and creative pedaling on the period instrument to express the complexity of these fluctuating emotions with great conviction.

Playfulness with hints of seriousness and gravity underlie the exuberant mood of this scherzo. Shebanova clearly expressed the emotional ambiguities that run like a vein though the work. The central section (lento, then sostenuto) in place of the Trio, gives one the impression so often with Chopin, of the ardent, reflective nature of distant love, love that has now passed with all its recalled yet pure illusions.

She excels in beautiful piano cantabile playing on the Erard, a song full of deepest reminiscence and meditation on the transience and fatal erosions of time. Later she brought a sense of growing triumphal resistance with an almost rough chiaroscuro tone, timbre and colour - music depicting an increasing exercise of sheer will to carry on with life. The culmination comes in the passionate final chords that close the work. Here Shebanova expressed a variety of enforced emotional desperation that expresses a courageous defiance of previously expressed uncertainties.

Heinrich Heine, a German poet who idolized Chopin, asked himself in a letter from Paris: ‘What is music?’ He answered ‘It is a marvel. It has a place between thought and what is seen; it is a dim mediator between spirit and matter, allied to and differing from both; it is spirit wanting the measure of time and matter which can dispense with space.’

I feel I must allow the superior and perceptive assessment of the great Polish musicologist Mieczyław Tomaszewski to introduce this set of mazurkas.

We do not know when Chopin

began work on the new set of mazurkas that he completed and published in mid

1842 as opus 50, dedicated – in a spontaneous gesture of friendship – to Leon

Szmitkowski, who took part in the November Uprising. Each of the three works

brings music of a different tone, yet they are linked by a mazurka idiom that

is no longer so directly dependent on music previously heard, on music brought

from home.

The new mazurka idiom was characterized by a personal tone of hushed intimacy.

There is a distinct trace – greater than the echo of rural music – of inner

experiences. Chopin’s mazurkas become more expressive than reflective, and it

is expression of an increasingly nostalgic tone. Even the shortest mazurka is

now a little poem with its own dramatic structure, though the first of the

three that comprise opus 50, in G major, brings the most numerous echoes and

folk references of that kind.

Shebanova and the Erard lift these mazurkas to a high plane of pianistic art. Especially that masterpiece, No 3 in C sharp minor, possesses such divine, expressive glowing delicacy in the tone and refinement of sound in its opening canon. The contrasts of homophony and polyphony are so transparent in the varied register colours of this period instrument. Her sense of improvised searching rhythm in the oberek and kujawiak, her variety of touch are deeply affecting in the creation of true intimacy and beauty of utterance.

Impromptu in G flat major Op.51 (1842)

Shebanova on the Erard transformed this into a delightful piece of charming salon music of a true poetic type, evocative of the finest intellectual aspirations and musical nature of such gatherings during nineteenth century, civilized Parisian life. André Gide, a discriminating musician and pianist himself, acutely described the beauty of the Chopin Impromptus in his Notes on Chopin (trans. Bernard Frechtman New York, 1949 p.41)

‘What is most exquisite and most individual in Chopin’s art, wherein it differs most wonderfully from all others, I see just that non-interruption of the phrase; the insensible, the imperceptible gliding from one melodic proposition to another, which leaves or gives to a number of his compositions the fluid appearance of streams.’

A concert given by Fryderyk Chopin in the salon of Duke Antoni Radziwiłł in 1829

Henryk Siemiradzki.

Waltz in E flat major Op.18 (1833)

Quite unlike the other recorded waltzes - full of charm, energy and delight. Chopin did not intend his waltzes or mazurkas for dancing but his sisters wrote and told him that many had been slightly modified into popular dances in Warsaw.

Ballade in F minor Op.52 (1842)

The great Polish musicologist Mieczysław Tomaszewski describes the musical landscape of this work far more graphically than I ever could.

The narration is marked, to an incomparably higher degree than in the previous ballades, with lyrical expression and reflectiveness [...] Its plot grows entangled, turns back and stops. As in the tale of Odysseus, mysterious, weird and fascinating episodes appear [...] at the climactic point in the balladic narration, it is impossible to find the right words. This explosion of passion and emotion, expressed through swaying passages and chords steeped in harmonic content, is unparalleled. Here, Chopin seems to surpass even himself. This is expression of ultimate power, without a hint of emphasis or pathos [...] For anyone who listens intently to this music, it becomes clear that there is no question of any anecdote, be it original or borrowed from literature. The music of this Ballade imitates nothing, illustrates nothing. It expresses a world that is experienced and represents a world that is possible, ideal and imagined.

This Ballade is the greatest of Chopin's 'stories in sound', a ballad without words. The genre of the literary ballade was well known of course but it had never before been designated as an instrumental work. Many such works by other composers were clearly programmatic in detail and delineated the character of the narrator and the setting. Not so with Chopin who took up a great compositional challenge. He managed the creative feat of composing a profound international and universal utterance through a national inspirational filter, namely the Poland of resistance and loss. In the words of Madame de Staël, he had begun to 'think in European' but beyond language to occupy the imagination.

Shebanova gave us an opening melody or 'song without words' of great innocence, flowering expressively, simply and sensitively through time. This developed into a more dramatic interpretation yet always punctuated with poetic lyricism and periods of reflection. The limited dynamic range of the Erard was particularly suitable for the cultivation of the contrast of moments of intimate meditation with more declamatory action.

This was a deeply musical view of the masterpiece in phrasing, rubato, polyphony and dynamic variation. I thought she emphasized the narrative declamatory elements and expressive polyphony with the greatest fatalistic self-reflection. The balladic tale of twists and turns was delineated with immense sensibility. At one moment we were given a work that was passionately lyrical, mercurially introspective, expressing that characteristic Polish bitterness, passion and emotionally-laden disturbance of the psyche known as żal.

What a monumental story of shifting realities is displayed in this work! Shebanova took us on a satisfying and poignant journey into this great opera of the inner human psyche, far beyond language to engage.

|

Menzel’s brother-in-law, Krigar, at the piano (1872) Adolph von Menzel (1815-1905)[Museum Oskar Reinhart] |

Polonaise

in A major Op.53

(1842)

The polonaise breathes and paints the whole national character; the music of this dance, while admitting much art, combines something martial with a sweetness marked by the simplicity of manners of an agricultural people . . . Our fathers danced it with a marvellous ability and a gravity full of nobleness; the dancer, making gliding steps with energy, but without skips, and caressing his moustache, varied his movements by the position of his sabre, of his cap, and of his tucked-up coat sleeves, distinctive signs of a free man and a warlike citizen. [The nineteenth-century poet and critic Kazimierz Brodziński]

By this time

the Chopin Polonaise had evolved an unapologetic subversive gesture, a piece of

'politically suspect' music. The Counsellor of State to the Russian Imperial

Court, Wilhelm von Lenz, wrote of ‘...his soul’s journey through . . .

his Sarmatian dream-world [...] Chopin was the only political pianist of the

time. Through his music he incarnated Poland, he set Poland to music!’

[Quoted in the ‘Chopin Bible’ Chopin: Pianist and Teacher as Seen by His Pupils, Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger, trans. Naomi Shohet with Krysia Osostowicz and Roy Howat, ed. Roy Howat (Cambridge 1988) p. 71]