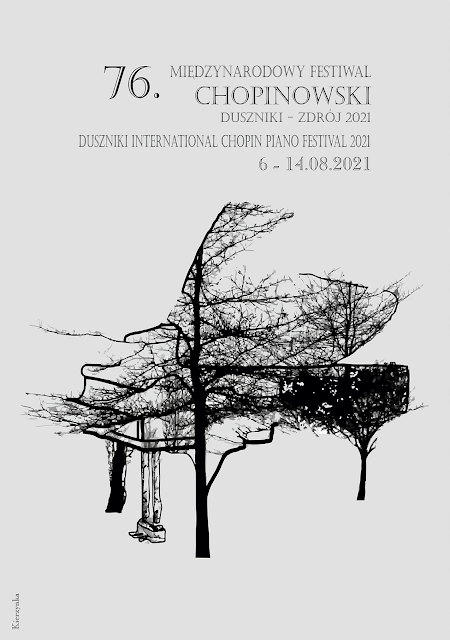

76th International Chopin Festival in Duszniki-Zdrój, 6-14 August 2021

Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen,

I again have the honour to welcome all the magnificent and steadfast friends of the Duszniki Festival.

Today we inaugurate the Chopin Festival for the 76th time.

Unfortunately, we again meet in Duszniki in conditions that only vaguely remind

what we have become accustomed to over all these years. Just like a year ago,

the festival we’ve prepared was ridden with massive uncertainty, amongst the

dynamic changes of the pandemic, extreme emotions, and concerns, but also the

hope that we will perhaps succeed with what we have found a highly risky task,

at times downright unfeasible.

I hope that after a range of the necessary corrections of the

previous assumptions, the festival will finally follow its final plan.

I would like to apologise for all the inconveniences, hindrances,

and surprising situations that may occur due to the continuing pandemic. All

the limitations and the necessary restrictions should and will be respected to

guarantee complete safety for the audience, artists, and organisers. We count

on your understanding and fully determined cooperation!

Despite a plethora of problems, I can assure you that the festival

concerts will, as usually, be long remembered. It has become a tradition of the

festival to open it, in the years of Chopin Competition, with the winner of its

previous round. This year we will host the magnificent Korean pianist Seong-Jin

Cho for the opening, and Eric Lu, another winner of the competition, who has

recently added the 1st Prize at the exceedingly prestigious Leeds Piano

Competition to the collection of his accolades, for the closing. After a few

years’ absence, we will again welcome to Duszniki Alexander Kobrin, winner of

the 3rd Prize of the 14th Chopin Competition, winner of the Van Cliburn,

Busoni, and Hamamatsu competitions. Alexander Kobrin will also conduct the

Master Classes at the festival with Professor Zbigniew Raubo.

On the 20th anniversary of death of the unforgettable Halina

Czerny-Stefańska, we will witness a particularly emotional concert, and welcome

her daughter, the dazzling harpsichordist, Elżbieta Stefańska, to the Chopin

Manor.

The recitals of artists whose previous concerts in Duszniki we hold

in our fond memories are highly likely to raise great interest. Antonio

Pompa-Baldi, the Genova & Dimitrov duo, Martin James Bartlett, Nikita

Mndoyants, and Daniel Ciobanu are the artists of the highest assay, performing

in the most prestigious concert halls on all continents. There are also four

artists coming to Duszniki-Zdrój for the first time. May I welcome this bevy of

consummate pianists – Nicolas Namoradze, Sofia Gulyak, Shiori Kuwahara, and

Maria Eydman – especially enthusiastically and warmly!

This year, the programme of our festival cannot fail to include Polish

pianists, instilling hope in us before the approaching Chopin Competition.

Keeping our fingers firmly crossed, let us wish them sincerely and eagerly all

the success and artistic satisfaction this October.

Words of my sincere gratitude for assistance and kind-heartedness go

to the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and Sport, and my special

thanks to the steadfastly unfailing Polish Radio 2, which will broadcast the

festival as it always has.

For the time of the festival, the Duszniki Spa Park will again turn

into a grand and beautiful concert hall, resounding with the music that will

reach the furthest corners of the world thanks to the live online streams by

Bydgoszcz-based Ros Media. I’d like to thank all the sponsors of the festival,

the authorities of the city and the region, and the media, whose kindness and

professionalism let us run our artistic and organisational tasks.

I thank all of you from the depth of my heart, Ladies and Gentlemen,

for the kind smile and for the countless proofs of trust and support that the

organisers of the festival have encountered, particularly in this especially

difficult time!

May you experience the very best of health and the most beautiful

emotions!

Piotr Paleczny

6 August 2021 Friday | time. 20.00 | Seong-Jin CHO |

August 7, 2021 Saturday | time. 4 p.m. | Piotr ALEXEWICZ Adam KAŁDUŃSKI Polish participants of the 18th Chopin Competition |

time. 20.00 | Antonio POMPA-BALDI | |

8/08/2021 Sunday | time. 4 p.m. | Jakub KUSZLIK Kamil PACHOLEC Polish participants of the 18th Chopin Competition |

time. 20.00 | Elżbieta STEFAŃSKA harpsichord (on the 20th anniversary of Halina Czerny-Stefańska's death) | |

9/08/2021 Monday | time. 4 p.m. | Piotr PAWLAK Andrzej WIERCIŃSKI Polish participants of the 18th Chopin Competition |

time. 20.00 | Martin James BARTLETT | |

10/08/2021 Tuesday | time. 4 p.m. | Alexander KOBRIN |

time. 19.00 | Opening of the exhibition of Wojciech Siudmak's drawings: ″ Nocturnes - Hommage a Chopin ″ (prepared by prof. Irena Poniatowska) | |

time. 22.00 | NOKTURN - The host of the evening: Róża Światczyńska | |

August 11, 2021 Wednesday | time. 4 p.m. | Nicolas NAMORADZE |

time. 20.00 | Nikita MNDOYANTS | |

August 12, 2021 Thursday | time. 11.00 a.m. | Concert of the participants of the 20th National Master Course for Pianists |

time. 4 p.m. | Maria EYDMAN | |

time. 20.00 | Daniel CIOBANU | |

August 13, 2021 Friday | time. 11.00 a.m. | Concert of the participants of the 20th National Master Course for Pianists |

time. 4 p.m. | Shiori KUWAHARA | |

time. 20.00 | GENOVA - DIMITROV Piano Duo | |

August 14, 2021 Saturday | time. 12.00 | Lecture by prof. Irena Poniatowska: ″ Chopin in poetry ″ |

time. 4:00 p.m. | Sofya GULYAK | |

time. 20:00 | Eric LU Final concert |

XX National Master Course for Pianists in Duszniki-Zdrój (Master Class)

August 7-10, 2021 - prof. Zbigniew RAUBO

11-14.08.2021 - prof. Alexander KOBRIN

* * * * * * * * * *

Internet broadcast link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qH3a7atTVEY

Saturday August 14, 2021 4:00 p.m.

Sofya GULYAK

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) /Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924)

Chaconne from II Partita No. 2 in D minor for solo violin (BWV 1004) (1720)

You

may read concerning the background to this work below, so I shall not repeat

myself.

I found Gulyak's performance contained nobility of spirit, great pianistic authority and formidable command of the keyboard. This was an highly accomplished reading of this demanding work. However, if one considers the tragic inspiration of the original Bach Chaconne, I felt I needed something more spiritual, a deeper penetration of the melancholy which immures the work could have spoken more directly to my heart of a possibly more universal human grief in the face of the ultimate reality of death. Certainly Busoni transforms, even inflates, the expressed emotion of Bach out of the baroque emotional universe into the world of a more personal romanticism and sense of tragic loss of a loved one.

The American musicologist Dr. Michael Markham perceptively observes in an essay:

'There is no evidence that Bach himself considered the chaconne to encode an entire vista of the universe or to sound out his own emotional depths. Such Romantic notions would never have occurred to a court composer who had trained in the late 1600s as a Lutheran town organist. Creating art then and there was not an act of personal expression but one of civic or religious service. Of course emotions could be depicted and messages delivered. But musicians of Bach’s generation did not need to feel an emotion in order to depict it. It was the next generation, beginning with Bach’s own son Carl Philipp Emanuel, who began to demand that a musician express emotions in a way we would call ‘authentic’.'

Johannes Brahms (whose deeply moving, personal Romantic works follow this piece), wrote of the original Bach violin work in a letter to Clara Schumann:

'On one stave, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I imagined that I could have created, even conceived the piece, I am quite certain that the excess of excitement and earth-shattering experience would have driven me out of my mind. If one doesn’t have the greatest violinist around, then it is well the most beautiful pleasure to simply listen to its sound in one’s mind.'

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Six Pieces for Piano Op. 118 (1893)

No. 1 Intermezzo in A minor

No. 2 Intermezzo in A major

No. 3 Ballad in G minor

No. 6 Intermezzo in E flat minor

|

| Brahms in his library 1895 |

'On one stave, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I imagined that I could have created, even conceived the piece, I am quite certain that the excess of excitement and earth-shattering experience would have driven me out of my mind. If one doesn’t have the greatest violinist around, then it is well the most beautiful pleasure to simply listen to its sound in one’s mind.'

The autumnal Brahms 6 Klavierstücke Op. 118 (1893) have always been close to my heart. In a letter to the conductor and composer Franz Lachner Brahms wrote (concerning the 1st Movement of the Second Symphony): 'I am, by and by, a severely melancholic person …black wings are constantly flapping above us'.

These are among the last compositions by Brahms and he seems to have conceived them as a coherent whole. It is hard to overlook the presence of the spectre of death that inhabits them. The group speaks volumes to me of the transient nature of human existence, but more of a proud philosophical resignation to the inevitability of destiny than a sensationalist expression of terror, despair and melancholy in the face of our mysterious journey to oblivion.

The passionate outbursts of the first Intermezzo in A minor, such an affirmation of life in those rich chords, then the fading away and decay. The second Intermezzo in A major marked Andante teneramente was played with deep feeling and sense of yearning. This ardent work, impossible for any musician to perform superficially, has all the rhapsodic yearning and longing of a nocturne on the nature of mortality and lost or fading love.

Brahms wrote to Clara:

Jan 25, 1855: Most Honored Lady, I can do nothing but think of you . . . what have you done to me? Can’t you remove the spell you have cast over me?

June, 1855: My dearly Beloved Clara, I can no longer exist without you . . . please go on loving me as I shall go on loving you, always and forever.

There is an almost vengeful affirmation of life contained within the Ballade in G minor with its vigorous rhythms and a wonderful delineation of densely woven harmonies.

The valedictory final piece of this integrated meditation on the acceptance of destiny and fate, the Intermezzo in E-flat minor, begins with the theme of the Dies Irae of the Christian requiem. The spectre of death enters and recurs in the work in various guises. Here we begin to inhabit another world far beyond this one. A strenuous, heroic yet tragic averral of the force of life briefly emerges but the terminal expression of resignation in death concludes pianissimo.

Clara Schumann wrote in her diary after receiving the pieces Op. 118 and Op. 119

'It really is marvelous how things pour from him; it is wonderful how he combines passion and tenderness in the smallest of spaces.

Variations in B flat major on a theme from Ludovic by Hérold/Halévy

(“Je vends des scapulaires”) Op. 12 (1833)

|

| Ferdinand Hérold (1791-1833) |

In May 1833, the Opéra Comique in Paris presented the premiere of Ludovic, the last opera by Ferdinand Hérold (1791-1833). This unfinished opera was completed by Fromental Halévy (1799-1862) and is rather simple and charming with pleasant melodies. Chopin, an opera connoisseur, attended this premiere. Ludovic was rather a flop apart from one of the ariettas or cavatinas ‘Je vends des scapulaires’ (‘I sell scapulars’). Chopin wrote some variations on that cavatina. Rather like Hérold’s opera, Chopin's style brillante piece did not attract lasting attention.

|

| Fromental Halévy (1799-1862) |

The work is rarely performed today. In the opinion of Schumann, compared with the composer’s other works it does not justify a note. James Huneker considered the Op. 12 Variations ‘the weakest of Chopin’s muse’, describing it as ‘Chopin and water, and Gallic eau sucrée at that’. Yet there are defenders. The Polish historian of music, composer and professor at the Jagiellonian University, Zdzisław Jachimecki (1882-1953), even found places in it that anticipated the harmonic revolution within Wagner’s Tristan. The German-Jewish musicologist Hugo Leichtentritt (1874-1951) liked what he called the ‘languid dolcissimo’ of the last variation, that he felt led towards Impressionism. There is no disagreement that this composition is, as the Polish historian Ferdynand Hoesick (1867-1941) excellently described it, as ‘thoroughly distingué and salon’.

With her brilliant digital facility and refined touch in addition to an ear for scintillating tone and sound, Gulyak gave an entertaining and delightfully charming account of the work in a true style brillante rendition of transparent clarity and delight.

INTERMISSION

César Franck (1822–1890)

Prelude, Fugue and Variations in B minor Op. 18 (1860–1862)

Prélude. Andantino

Lento

Fugue. Allegretto ma non troppo

Variation. Andantino

|

| Rennes Cathedral, Ille-et-Vilaine, Bretagne, France. Cavaillé-Coll organ dating from 1874, totally rebuilt by Haerpfer-Erman in 1970. Instrument with 4 manual keyboards, 67 registers and 4953 pipes. |

In an usual choice, Gulyak selected an organ work to perform on the piano. The Prelude, Fugue, and Variation Op. 18, originally for organ, was dedicated to the composer Camille Saint-Saëns, who was also an organist among his many music accomplishments.

During the second half of the 19th century, the geographical influence of music written for organ moved from Germany to France under the tutelage of the organ builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. He built some 5000 organs replete with many technical advances. His instruments inspired the Belgian composer César Franck (1822-1890) who was the organist at churches that featured Cavaillé-Coll organs, even representing the company artistically. In 1858 he was appointed organist at the basilica of St. Clotilde in Paris with its outstanding Cavaillé-Coll instrument.

Franck loved to improvise, was highly popular in this activity. He even wrote some of his improvisations down and published them as his Six pièces pour Grand Orgue. This work is the third of these pieces that so deeply influenced the French organ school.

Gulyak's performance of this rarely heard Romantic work in a concert room on the piano was an attractive and moving example of balance, polyphonic transparency and clarity.

Richard Wagner (1813–1883) / Franz Liszt (1811–1886)

Tristan und Isolde – Liebestod WWV 90 (1859)

|

| Rogelio de Egusquiza (1845-1915) Tristan and Iseult (1910) |

One must never forget the constraints of instruments that brought about such transcriptions and the extraordinary service the selfless Liszt performed for keyboard players in the nineteenth century who were without ready access to an organ or the services of an orchestra. We are indeed richly endowed today and tend to forget this when maligning the great Ferenc for his generous transcriptions of everything under the sun.

This was a fine, musical performance but on the level of the psyche, embracing the fulfillment or 'peaceful release' offered by death, carried unresistant on the cresting wave of metaphysical and passionate love, then I felt this dimension escaped Gulyak. Was she possibly innocent of the lacerations and joys of love inflicted by the tigers of experience? Highly unlikely. However, the building of the erotic curve in a smooth, sensually rising line to the orgasmic climacteric, the apotheosis of the metaphysical symbiosis of love/death that Wagner embraces, is a tremendously demanding pianistic task to express, to discipline and to communicate effectively.

Wagner's debt to the harmonic adventurism of Liszt, the Tristan chord, is never in doubt to my mind. The work is a musical and personal challenge to depict this merging of the lovers in death, situated predominantly and 'deep darkly' in the mind of Wagner. An excellent performance nevertheless.

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

La Valse M 72 (1919–1920)

|

| COURT BALL AT THE HOFBURG Dance in the public ballroom of the Imperial Palace, Vienna. Watercolor by Wilhelm Gause, 1900. Emperor Francis Joseph is on the far right |

Diaghilev had requested a four-hand reduction of the original

orchestral score. Reports say that Stravinsky when he heard Ravel perform this

with Marcelle Meyer in this version, he quietly left the room without a word so

amazed was he. Ravel however would not admit to the work being an expression of

the profound disillusionment in Europe following the immeasurable human losses

and cruel maiming of the Great War. However one must recall in Thomas Mann’s

Dr. Faustus that the composer Adrian Leverkühn, although isolated from the

clamour and destruction of the cannons of war, composed the most profound

expression of it in his composition Apocalypsis cum Figuris by a type of

metaphysical osmosis. Ravel’s note to the score gives one an insight to his

intentions:

Ravel described his composition as a ‘whirl of destiny’ – his concept was that the work impressionistically begins with clouds that slowly disperse to reveal a whiling crowd of dancers in the Imperial Court of Vienna in 1855. The Houston Symphony Orchestra programme note for the orchestral version performed in 2018 poses the question: Is this a Dance of Death or Delight ? I feel the question encapsulates perfectly the ambiguity inherent in this disturbing work. A composer can sometimes be a barometer that unconsciously registers the movements of history.

An excellent performance of this magnificent work, for me just lacking the final feeling of abandoned, perhaps even insidious excitement that accompanies premonitions of disaster.

Internet broadcast link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_pVBMgqIFhU

Friday August 13, 2021 20.00

GENOVA - DIMITROV Piano Duo

I remember so well the highly entertaining programme this duo presented at Duszniki in August 2015. On that occasion I wrote:

They opened their programme with the Chopin Rondo in C major Op. posth. for two pianos. This is a delightful and charming styl brillant piece to which they did full justice.

Then onto the Romantic music of the Russian composer, pianist and professor Anton Arensky (1861-1906). We heard the Suite No.3 Op.33, Variations for two pianos. I would highlight the charming and elegant Variation 4 Valse; Variation 5 Menuet rather like a children's music box; Variation 6 Gavotte - a childlike, innocent piece in the baroque style; Variation 7 Scherzo - a true joke quite unlike a darkly dramatic Chopin Scherzo;Variation 9 Nocturne a gentle and elegiac piece that followed Variation 8 Marche Funebre. An absolute pleasure.

After the interval the Grieg Peer Gynt Suite Op.46 for piano and four hands. Anitra's Dance was especially memorable for the terrific rhythmic impetus.

The Borodin Polovtsian Dances from the opera Prince Igor arranged for two pianos by Victor Babin was absolutely splendid outpouring of physical energy and bubbling joy.

Finally the Liszt Reminiscences de Norma de Bellini arranged for two pianos. Of course Liszt performed a marvelous service with such works. Without the record industry as we know it, music lovers would only be likely to hear the opera perhaps once in their lives if at all. Providing piano versions and transcriptions of such works Liszt with infinite labour provided pianists and the domestic environment with opportunities of endless hours of uplifting delight. I must say I found this work rather overblown for my taste verging on the humourous at some of the wonderfully excessive Lisztian moments.

The Rachmaninoff programme they designed on this occasion reflected significant thought. The first half of the recital was devoted to works written or transcribed for four hands by the youthful composer. The second half was entirely devoted to his final major work for the piano written for four hands.

”Rachmaninoff Happening”

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943)

|

| Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1892 at the age of 19 |

This work is a fantasia or symphonic poem for orchestra written by Rachmaninoff in the summer of 1893 and dedicated to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. It is an atmospheric work, inspired by Russian literature, specifically two lines by the poet Lermontov. Despite having been composed during Rachmaninoff’s young years, The Rock already shows a large spectrum of the Russian composer’s musical sensitivity and ability to depict highly dramatic narratives.

It is easy to underestimate in our time of social media, an era of short texts and even shorter attention spans, the profound influence of poetry and novels on nineteenth century composers. Poetry was regarded by some as a higher art than music. This was not the case in this highly poetic and allusive performance.

Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841)

The Rock

Upon the breast of a huge rock;

And cheerfully at dawn it dashed

Into the blue not to come back

Wet traces in the crevices

Of ancient stone like tears remained;

And deep in thought alone it stands

And weeps into the distant void.

(trans. Don Mager)

This poem also inspired Anton Chekhov to write his short story On the Road that depicts an older man staying at an inn where he meets a younger woman. He tells her about all the tragedies that affected his long life. A blizzard rages outside. Using the imagery of Chekhov and Lermontov, Rachmaninoff created this atmospheric work.

|

A Troika in a Blizzard (1881) Nikolai Sverchkov (1817-1898) was a Russian painter who focused on outdoor scenes, mostly in winter. |

From Anton Chekov On the Road

'Outside a storm was raging. Something frantic and wrathful, but profoundly unhappy, seemed to be flinging itself about the tavern with the ferocity of a wild beast and trying to break in. Banging at the doors, knocking at the windows and on the roof, scratching at the walls, it alternately threatened and besought, then subsided for a brief interval, and then with a gleeful, treacherous howl burst into the chimney, but the wood flared up, and the fire, like a chained dog, flew wrathfully to meet its foe, a battle began, and after it -- sobs, shrieks, howls of wrath. In all of this there was the sound of angry misery and unsatisfied hate, and the mortified impatience of something accustomed to triumph.'

Rachmaninoff introduces a theme that is a metaphor for the desire connecting the two characters during the night. In the morning the woman leaves the inn and we are left with this dark theme, which we can identify with solitude and sorrow.

'"Well, God help you," muttered Liharev, tucking her into the sledge. "Don't remember evil against me . . . ."

She was silent. When the sledge started, and had to go round a huge snowdrift, she looked back at Liharev with an expression as though she wanted to say something to him. He ran up to her, but she did not say a word to him, she only looked at him through her long eyelashes with little specks of snow on them.

Whether his finely intuitive soul were really able to read that look, or whether his imagination deceived him, it suddenly began to seem to him that with another touch or two that girl would have forgiven him his failures, his age, his desolate position, and would have followed him without question or reasonings. He stood a long while as though rooted to the spot, gazing at the tracks left by the sledge runners. The snowflakes greedily settled on his hair, his beard, his shoulders. . . . Soon the track of the runners had vanished, and he himself covered with snow, began to look like a white rock, but still his eyes kept seeking something in the clouds of snow.'

Six Morceaux Op. 11, for piano four hands (1893–1894)

Composed

in 1894, the Six Morceaux Op. 11 for piano four-hands is a fine

composition following Rachmaninoff’s youthful studies at the Moscow

Conservatory.

This highly entertaining work was performed with enormous panache and style by the duo.

The opening Barcarolle is dark and mysterious, its gently rocking rhythms depicting a gondolier navigating the Venetian canals beneath a moonlit sky. Eloquently performed.

The Scherzo is vivacious and brilliant composition with irresistible rhythm. This was brought off with intense authority and elan.

The Chanson Russe is a set of variations on an unknown folk song. A terrific idiomatic Russian piece to my mind whose essence the duo had no trouble in capturing! The duo have a formidable control over the tonal balance, coherence and co-ordination.

Finally the highly familiar Slava! (Glory). This is a set of variations based on a Russian chant used by Mussorgsky in Boris Godunov. A triumphal conclusion by the duo to this highly entertaining set of pieces.

INTERMISSION

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943)

Symphonic Dances Op. 45, for 2 pianos (1940)

Non Allegro

Andante con moto. (Tempo di valse)

Lento assai – Allegro vivace

Rachmaninoff wrote his last major work, the Symphonic Dances, on vacation at his Long Island summer house in the summer and autumn of 1940.

The first movement Non Allegro is built upon a traditional sonata form and muscular, sometimes whimsical themes but infused with Rachmaninoff’s unique and particularly soulful nostalgia. Genova and Dimitrov are strikingly symbiotic in their interpretation of music for four hands or two pianos and play as if they had become one reactive and expressive organism. Listening to them is an uncanny experience to say the least.

The second movement Andante con moto. (Tempo di valse) is an extended waltz, although the Viennese 3/4 waltz rhythm is notably absent. The music reflects shadows of regret and painful melancholic memories.

The final movement Lento assai – Allegro vivace is rather percussive and tremendously stimulating. Some sections are derived from Spanish dances such as the jota and the seguidilla. The chromatic middle section is nostalgic and poignant. The Dies irae chant from the Gregorian Requiem Mass makes an appearance emphasising that disillusion and death are always lurking and haunting the musical shadows of this Russian composer. Rachmaninoff first used this lugubrious chant in the First Symphony of 1895. In a sudden access of almost forced optimism he introduces a new motif in the coda marked 'Alliluya' to end the work on a brilliant note.

This was a scintillating and atmospheric performance of this demanding work.

|

| Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1940, the year of the Symphonic Dances |

Their first encore was an exciting performance of an arrangement for four hands and two pianos of the famous Rachmaninoff Prelude in C-sharp minor Op.3 No:2

Their second encore was the rather touching and romantic Romance in G major for four hands on one piano also by Rachmaninoff. Surely chosen to reflect certainly their musical and perhaps personal intimacy too!

A deeply satisfying recital on every musical level.

* * * * * * * * * *

Internet broadcast link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8E-nPU8XVQ4

Friday August 13, 2021 4 p.m.

Shiori KUWAHARA

This was without doubt the most impressive, riveting and startling recitals of the entire Duszniki Festival so far this year. Magnificent musicianship and pianistic command.

A formidable Japanese pianist unlike any other I have ever heard. An individual voice.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Piano sonata in A flat major Op. 110 (1821)

Moderato cantabile molto espressivo

Allegro molto

Adagio ma non troppo

Arioso dolente

Fuga. Allegro ma non troppo

|

| Moonlight Landscape (before 1808) Caspar David Friedrich (The Morgan Library&Museum, New York) |

The great musicologist and pianist Charles Rosen (sadly no longer with us) in his book on the Beethoven piano sonatas notes that Beethoven in this work does not ‘simply represent the return to life, but persuades us physically of the process.’ The work is an ambitious choice to open a recital for any young spirit, although here we have a mature pianist. There was deep maturity in this interpretation which was evident to me from her very first notes.

Kuwahara gave the opening Moderato cantabile molto espressivo the nature of a contemplative consideration of a tumultuous life with gathering shadows of depression. Such feelings are common during the travails of serious illness.She began with a pleasant, rather blithe, observance of the instruction con amabilità. Donald Tovey compared the artful melodic simplicity of the development with the entasis of the Parthenon's columns. Structurally adventurous, its features scarcely resemble those of any of his previous sonata movements. Musicologists have called the following Allegro molto robust and humorous but is this truly so? The movement is supposedly based on popular songs of which Beethoven was not particularly fond: 'Our cat has just had kittens' and even more typically Beethovinian and roughly hewn 'I'm dissolute, you're dissolute'.

His extreme temperament passes rather dramatically into yet another phase in this 'Anatomy of Melancholy' in the Adagio ma non troppo - Allegro ma non troppo. Composed in 1821, it becomes clear as it progresses that this sonata is the most personally reflective of the Beethoven sonatas. He was by this time profoundly deaf and was communicating using the depressing conversation books. It is well to remember a passage from the Heiligenstadt Testament of 1802:

My misfortune is doubly painful to me because I am bound to be misunderstood; for me there can be no relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas. I must live almost alone, like one who has been banished; I can mix with society only as much as true necessity demands. If I approach near to people a hot terror seizes upon me, and I fear being exposed to the danger that my condition might be noticed. Thus it has been during the last six months which I have spent in the country. By ordering me to spare my hearing as much as possible, my intelligent doctor almost fell in with my own present frame of mind, though sometimes I ran counter to it by yielding to my desire for companionship. But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone standing next to me heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me almost to despair; a little more of that and I would have ended my life - it was only my art that held me back. (A passage from the Heiligenstadt Testament © Translation John V. Gilbert)

There is such pain and exhaustion here. The composer was recovering from the debilitation of a crippling illness and the great human attempt to rise above it, resistance heroism in a word. This movement is one of Beethoven’s most anguished and embattled utterances. The third movement's structure alternates two slow arioso sections with two faster fugues. In Alfred Brendel's analysis, there are six sections – recitative, arioso, first fugue, arioso, fugue inversion, homophonic conclusion. In contrast, Martin Cooper describes the structure as a 'double movement' (an Adagio and a Finale). The arioso is marked Klagender Gesang (Song of Lamentation).

The initial Fugue is by driven an existential anger that Kuwahara made impressively expressive and anguished. Yet this fugue is irresolute and unfinished in its impetus. The second fugue emerges after a second arioso (rare in instrumental music except Bach). Donald Tovey describes the broken rhythm of this second arioso as being 'through sobs'. The subject of the second fugue is that of the first inverted, marked wieder auflebend (again reviving) and poi a poi di nuovo vivente (little by little with renewed vigour – written in the traditional Italian). A painful return to life is evolving and grows irresistibly in strength.

The emotions remain raw and conflicted. Here was a man as well as composer of genius who cared little for the state of his pianos (food left inside, full chamber pots underneath, legs sawn off) sacrificing all physical comfort and luxury to his cosmic spiritual conceptions, even overlooking the difficulties executants may have had to face performing his music.

A splendid and satisfying idiomatic performance of Beethoven, quite unlike any Japanese pianist I have previously encountered.

Ferenc Liszt (1811-1886)

Sonata in B minor S.178 (1852–53)

We had all expected Schubert's Wanderer Fantasy when the ominous opening G octaves sotto voce instantly announced the Liszt B minor Sonata. This was a superbly dramatic imagined conceit by Kuwahara, as the Schubert Fantasy had deeply influenced the form of the sonata. Talk about spontaneity! Liszt not only introduced the Wanderer Fantasy to the public, but also transcribed it for piano and orchestra in 1851, shortly before writing his sonata. He also transcribed for piano solo the song on which Schubert based his Fantasy.

This famous Sonata was published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1854 and first performed on January 27, 1857 in Berlin by Hans von Bülow. It was attacked by the German Bohemian music critic Eduard Hanslick who said rather colourfully ‘anyone who has heard it and finds it beautiful is beyond help’. Among the many divergent theories of the meaning of this masterpiece we find that perhaps:

The Sonata is a musical portrait of the Faust legend, with 'Faust,' 'Gretchen,' and 'Mephistopheles' themes symbolizing the main characters. (Ott, 1981; Whitelaw, 2017)

- The Sonata is spiritually autobiographical; its musical contrasts spring from the conflicts within Liszt’s own personality. (Raabe, 1931)

- The Sonata is about the divine and the diabolical; it is based on the Bible and on John Milton’s Paradise Lost (Szász, 1984)

- The Sonata is an allegory set in the Garden of Eden; it deals with the Fall of Man and contains 'God,' 'Lucifer,' 'Serpent,' 'Adam,' and 'Eve' themes. (Merrick, 1987)

- The Sonata has no programmatic allusions; it is a piece of expressive form with no meaning beyond itself. (Winklhofer, 1980)

- Could Liszt have been inspired by the words of the the poem by Schmidt von Lübeck that inspired Schubert to write his song and the Fantasy? Perhaps the sonata is a variety of programme music, a genre which always appealed to Liszt the spiritually isolated 'Wanderer'. A man who was not only a theatrical virtuoso pianist but within a solitary religious man, a composer-explorer and creator of new harmonic worlds.

The manner in which a pianist opens this masterpiece tells you everything about the conception that will evolve. The haunted repeated notes Pietraszak produced were of an eloquent duration (a terrible battle lies in wait for pianists here - Krystian Zimerman drove his recording engineers mad repeating it hundreds of times before finally being satisfied). Her duration and dynamic boded well for the outcome of the sonata. She created from the outset an atmosphere of ominous presentiment and premonition, a kernel seed from which the sonata would organically flower.

What did Kuwahara have to say about this work ? This is a profound piece, too often played as some type of hectic fantasy or impassioned dream fantasy, although that was not the case here.

The sonata is actually in many respects a philosophical dialogue between different fundamental aspects of the human spirit as symbolized by Faust, Mephistopheles and Gretchen. Liszt was tremendously influenced by literature and poetry in his compositions and in particular Goethe’s Faust, the dramatic spiritual battle between Faust and Mephistopheles with Gretchen hovering about as a seductive, lyrical feminine interlude. And the whole is a highly complex musical and structural argument.

Kuwahara gave an emotionally moving, impassioned, idiomatic and dramatic account of this formidable sonata with complete command of the keyboard in addition to penetrating musicality. A great opera of life unfolded under her fingers. Her silences were perfectly judged to touch the nervous system with haunting phrasing that encompassed the tragic Romantic temperament in its concentrated essence. The mighty Fugue was polyphonically transparent and noble in dimension and tempo.

I experienced the smell of sulphur and the diabolical in this performance. Religiosity, passion, hell, introspection, love - an entire man's life held up to inspection and then the quite heavenly conclusion. Her pianissimo was ravishing. I imagined angels carrying the soul aloft into the ether. Her approach to Liszt surely indicated a reading or at least deep awareness of the of the Byronic literature of the period that reflected the fraught evolution of this remarkable life narrative.

Kuwahara communicated a magnificently well-integrated conception of this mighty edifice. One of the finest performances I have heard and I repeat, a splendid monumental interpretation quite unlike any Japanese pianist I have previously encountered.

An instant standing ovation. A rare occurrence at Duszniki especially before the intermission.

INTERMISSION

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) / Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924)

Chaconne from Partita No. 2 for solo violin in D minor BWV 1004 (1720)

It is a well known fact that in his writing for the pianoforte Busoni shows an inexhaustible resource of color effect.... This preoccupation with color effects on the pianoforte began to make itself evident after Busoni had began to devote himself to the serious study of Liszt, but it remained to dominate his mind up to the end of his life.

[Edward J. Dent, Ferruccio Busoni. A biography (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966), pp. 145-146]

I have always liked this work transcribed by Busoni 1891-2. Bach occupied and inspired the composer for his entire life. 'Bach is the foundation of pianoforte playing,' he wrote, 'Liszt the summit. The two make Beethoven possible.' It is not surprising then that the grandeur, invention and monumentality of the Chaconne from this Partita attracted his imaginative mind. Bach himself, he notes, was a prolific arranger of his own music and that of other composers.

'Notation is itself the transcription of an abstract idea. The moment the pen takes possession of it the thought loses its original form.'

Bach had composed it after learning in 1720 of the death of his beloved wife Maria Barbara, the mother of his first seven children. Bach had been in Karlsbad with his patron, the highly musical Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. When Bach returned to Cöthen after three months he discovered his young wife of 35, who was in excellent health when he departed, had died during his absence and even worse, been buried. His grief-stricken response resulted in this composition for violin full of pain, suffering and melancholic nostalgia, even anger, at the indiscriminate nature of destiny.

Kuwahara opened the work with the greatest nobility of utterance and poise. Sheer virtuosity did not tempt her as it might have many lesser pianists. Busoni was as concerned with degrees of expressiveness as any Romantic composer.

The transparent polyphony of the twenty-nine variations of the work was impressive. Her pedalling was superbly artful which gave intense colours within the soundscape. The melodic lines and the weight and significance of chords was always in grand aesthetic conception. Much of the music was intended to reflect the sound of a magnificent seventeenth century Thuringian organ and its 16' stop which she accomplished. Kuwahara gave the work a noble and triumphal concluding resolution and completion.

I felt I had nothing left to say after this authoritative and imposing performance.

A rare picture of Ferrucio Busoni playing a pedal harpsichord with a 16' stop, possibly an inspiration for his Bach organ transcriptions that naturally were transformed into something highly pianistic.

Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924)

Elegies: No. 7 “Lullaby” (1909)

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Petrushka K 12 (1910–1911)

Russian dance

Petrushka’s Room

The Shrovetide Fair

|

Petrushka The puppets - The Moor, the Ballerina, Petrushka and the Charlatan (Photo © Dave Morgan) |

* * * * * * * * * *

Internet broadcast link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lMNVJFZmsiI

Thursday August 12, 2021 20.00

Daniel CIOBANU

Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

Kreisleriana Op. 16 (1838)

Äusserst bewegt

Sehr innig und nicht zu rasch

Sehr aufgeregt

Sehr langsam

Sehr lebhaft

Sehr langsam

Sehr rasch

Schnell und spielend

Ciobanu opened his recital with one of my favourite works of romantic piano literature Kreisleriana Op. 16 by Robert Schumann. Please excuse me if you have read this introduction before but I can see no point in endlessly recasting established history.

Madness or insanity was a notion that throughout the composer's time on earth, simultaneously attracted and repelled Schumann. At the end of his life he was cruelly to fall victim to it. Kriesleriana was presented publicly as eight sketches of the fictional character Kapellmeister Kreisler, a rather crazy conductor-composer who was a literary figure created by the marvellous German Romantic writer E.T.A. Hoffman. The piece is actually based on the Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier and also the form of an inventive grotesque satirical novel Hoffmann wrote with the remarkable, translated title: Growler the Cat’s Philosophy of Life Together with Fragments of the Biography of Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler from Random Sheets of the Printer’s Waste.

The fictional author of this novel, Kater Murr (Growler the Cat), is actually a caricature of the German petit bourgeois class. In a theme rather appropriate in our times of gross financial inequalities, Growler advises the reader how to become a ‘fat cat’. This advice is interrupted by fragments of Kreisler’s impassioned biography. The bizarre explanation for this is that Growler tore up a copy of Kreisler’s biography to use as rough note paper. When he sent the manuscript of his own book to the printers, the two got inexplicably mixed up when the book was published. Such devices remind one of Laurence Sterne in that great experimental novel Tristram Shandy.

Schumann was particularly fond of Kreisleriana. He was attracted to composing works in ‘fragmented’ form in the structural manner of this Sterne novel. The use of the device of interrelated ‘fragments’ (as the nineteenth century termed what we might refer to as 'miniatures') was employed by the Romantic Movement in poetry, prose and music.

Kreisler is a type of Doppelgänger for Schumann. This was a favourite concept for the composer, who divided his own creative personality between the created characters of Florestan and Eusebius. With the unpredictable Kreisler as his alter ego, Schumann was able to indulge the dualities of his own personality. The music swings violently and suddenly between agitation (Florestan) and lyrical calm (Eusebius), between dread and elation. The episodes in the piece describe Schumann's emotional passions, his divided personality and his creative art. His tortured soul alternates with lyrical love passages expressing the composer’s love for Clara Wieck. He used and transformed one of her musical themes in the work.

1838 was a disturbed time for Schumann. His marriage to this 'inaccessible love', the piano virtuoso Clara Wieck, was a year ahead. At this time they were painfully petitioning the courts for permission to marry and ignore her father's cruel social class objections to the connection. They had known each other for ten years before their eventual marriage in 1840. During this turbulent period of frustration, Schumann’s compositions evolved in complexity. Their unbridled emotionalism and adventurous structure confused musicians, audience and critics alike.

He originally intended to dedicate the work to Clara, but wishing to avoid more calamitous situations with her father he eventually dedicated it to his friend Fryderyk Chopin. The polyphonic nature of the piece may have reflected a deep understanding of Chopin's own polyphonic style. The Polish composer merely commented on the cover design of the score left on his piano. Even Clara, on first acquaintance with the work, wrote: 'Sometimes your music actually frightens me, and I wonder: is it really true that the creator of such things is going to be my husband?' Even Franz Liszt was challenged finding the work 'too difficult for the public to digest.'

This great masterpiece of emotional and structural complexity, expresses much of the quixotic mercurial temperament of Schumann's personality and the literary elements of the story. The French literary theorist and Schumann-lover Roland Barthes interestingly observed that Schumann composed music in discrete, intense 'images' rather than as an evolving musical 'language', like a succession of frames in a film. The composer was experimenting with the timbre of piano sound. Without wishing to appear a 'crank', I feel it necessary to say that on a piano of Schumann's period (he loved Clara's Viennese Conrad Graf of 1838) the varied colours, timbre and textures of the different registers suited the contrapuntal nature of composition. This would have been rather more obvious on the older instrument than on the modern, homogenized Steinway.

I felt Ciobanu oddly 'off-form' in this work. He produced an ardent cantabile tone, true love poems with some very sensitive, lyrical and nuanced moments. However, I felt the contrast of the two sides of Schumann's Doppelgänger nature was not sufficiently integrated. Such a temperamental and capricious work by Schumann (and the bizarre background story by E.T.A.Hoffmann) is immensely difficult to present with conviction and lucidity. I felt this unpredictable, spontaneous, quick-silver moody aspect of the composer escaped Ciobanu rather. The energetic, fragmented driving, almost pathological qualities of Florestan were not coherently organic with his feeling for the lyrical Eusebius qualities of the piece. These matters are a delicate question of balance in this challenging work.

INTERMISSION

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

Scherzo in B flat minor Op. 31 (1836–1837)

The

opening repeated triplet group gives a perfect indication of the pianist's

conception of this popular work.

I felt that Ciobanu failed to understand the existential significance of the key triplet figure which gives such gravity and the atmosphere of darker philosophical intent to the entire work that develops. I felt we did not receive a sufficiently threatening and ominous vision of this much maligned and often performed work, known informally and possibly pejoratively as the 'governess scherzo' (every musically accomplished governess of aristocratic children played it).

Mieczysław Tomaszewski writes of this scherzo: 'The new style, all Chopin’s own, which might be called a specifically Chopinian dynamic romanticism, not only revealed itself, but established itself. It manifested itself à la Janus, with two faces: the deep-felt lyricism of the Nocturnes Op.27 and the concentrated drama of the Scherzo in B flat minor.'

Arthur Hedley thought about the work’s ecstatic lyricism, before concluding in a way even more appropriate today in the age of recording: ‘Excessive performance may have dimmed the brightness of this work, but should not blind us to its merits as thrilling and convincing music.’

Dan Dediu (b. 1967)

Les barricades mysterieuses (ed. 2006)

I was unfamilar with the life and work of this modern Romanian composer but this work was pleasing with its nod to the superb harpsichord piece by Francois Couperin

Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

Piano sonata No. 7 B flat major Op. 83 “Stalingrad” (1939–1942)

Allegro inquieto

Andante caloroso

Precipitato

This is one of the three great Prokofiev 'War Sonatas'. The percussive anger of the Allegro inquieto was expressed with great energy as was the lyrical contrast of the emotional and romantic Andante caloroso. That plaintive repeated note that for me expresses all the intense loneliness and isolation of the human soul and psyche in the firmament confronted by the cruelty of war in Stalingrad. Ciobanu captured this bleakness well. The Precipitato final movement was as driven and powerful as I expected from this historical painting in sound. The movement is of great cumulative power leading to an overwhelming resolution and harmonic climacteric.

|

| The Soviets regain control of Stalingrad in February 1943. (SVF2/UIG via Getty Images) |

* * * * * * * * * *

Internet broadcast link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EKWzxWXijso

Thursday August 12, 2021 4 p.m.

Maria EYDMAN

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

Étude in F major Op. 10 No. 8 (1829–1832)

The sparkling dispatch of this Etude by this young, multiple first prize-winning artist, gave us a foretaste of the future recital accomplishments we might expect. The control of the transparent internal polyphony and articulation, particularly in the left hand, was a revelation to me at least.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Piano sonata in F major Op. 10 No. 2 (1796–1798)

Allegro

Allegretto

Presto

This is not a sonata where, as Alfred Brendel observes, the audience should expect 'the celebration of religious rights'. The opening Allegro is quite humorous, whimsical and full unanticipated twists and turns of harmony. Eydman expressed this light-hearted consciousness to a modest degree. This opening movement was balanced by the seriousness of the Allegretto in F minor which she made a suitable contrast in mood. The Presto was certainly energetic but I felt rather too heavy in tone and tempo to take me away with on a flight of light, joyful laughter.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770‒1827)

32 Variations in C minor on an original theme WoO 80 (1806)

This work dates from the end of 1806, the year of the ‘Razumovsky’ quartets, the fourth symphony and the violin concerto. It is a quite remarkable homage to the Baroque era and is a fine example of Beethoven's veritable obsession with variation form. These are elaborations on the chaconne dance form which fully evolved under the reign of Louis XIV.

This was an impressive pianistic exegesis, full of winning articulation and variety of tone, colour and touch. However, I felt in some variations an excess of virtuosity and falling prey to the temptations of keyboard fluency and exaggeration, only possible to this extent with the streamlined action and rather homogenized sound of the Steinway. Is this a bad thing?

I am not a crank advising sole performance on say Beethoven's Graf. However, playing occasionally on the earlier instrument one can learn a great deal when listening closely to the extraordinary variety Beethoven conceived possible for each variation in dynamics, colour, texture, mood and timbre. The modern pianist should make some attempt to express and transfer this contextual knowledge to the modern instrument. I found this an impressive but rather unapologetic Lisztian approach to Beethoven which created all manner of period contradictions in my mind.

Béla Bartók (1881–1945)

Sonata Sz.80 (1926)

Allegro moderato

Sostenuto e pesante

Allegro molto

Despite 1926 being 'the year of the piano' for Bartok, I am simply unable to react to this sonata in any positive personal way. I love the 'Out of Doors Suite' of the same period for example and the piano concerto. The first two movements of the sonata I find relentless, brutal and bleak - not at all the way I choose to see the world. Yes the folk dance elements in the final movement are somewhat of a relief, but I felt Eydman could have invested the declamatory dynamics of the work with at least some poetic expressive elements. It can be done!

György Ligeti (1923–2006)

Études, Book 1 (1985)

No. 6 “Autumn in Warsaw”

I had never heard this work before although naturally I knew of the contemporary Warsaw Autumn music festival. It is the only contemporary music festival in Poland on an international scale and with an international status. For many years, it was the only event of this type in Central and Eastern Europe.

My ignorance causes me to quote directly from the Hyperion CD liner note written by the pianist Danny Driver.

Automne à Varsovie (‘Autumn in Warsaw’), dedicated ‘à mes amis Polonais’ at a time of political struggle in Poland, is an extended étude where Johannes Ockeghem’s prolation technique (a single motif proceeding simultaneously at different speeds in different voices), pulsating African polyrhythm and Ligeti’s characteristic lamento motif (inspired by the Romanian bocet—a funeral lament chanted by professional mourners) combine in a nostalgic and ultimately tragically ruptured musical canvas.

Certainly Eydman produced arresting musical timbres, extraordinary sound quality and colour, often laid upon a glittering canvas that I attempted to connect with the liner notes. After the Bartok, I found this work was quite a task to tolerate aurally, despite my own studies of contemporary piano music and the so-called avant-garde.

INTERMISSION

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943)

Études – Tableaux Op. 39 (1916–1917)

No. 1 in C minor Allegro agitato

No. 2 in A minor Lento assai

No. 4 in B minor Allegro assai

No. 8 in D minor Allegro moderato

No. 3 in F sharp minor Allegro molto

These 'study-pictures' reveal to a haunting degree Rachmaninoff's internal psyche like few other works he wrote. However we are not given a guide to the 'pictures' which is rather in the spirit of Chopin's remark concerning his own work 'I merely indicate, the listener must complete the picture'.

I felt this highly talented young pianist could have given us more of an indication of painting in sound. She could have made much more of the painterly and suggestive qualities of these works (as much as one can visualize 'a story' in imagination from the music), their colour palette, rather than simply revelling in the virtuoso elements. She cultivates on occasion a rather, almost metallic, hard-edged percussive sound palette, not the quality of impressionist painting which is surely far softer and suggestive rather than declamatory and wildly virtuosic. This performance only occasionally expressed the inner emotionally eloquent heart of Rachmaninoff.

What is Music? How do you

define it? Music is a calm moonlit night, the rustle of leaves in Summer. Music

is the far off peal of bells at dusk! Music comes straight from the heart and

talks only to the heart: it is Love! Music is the Sister of Poetry and her

Mother is sorrow! (Sergei Rachmaninoff)

|

| A youthful Scriabin |

Alexander Scriabin (1871–1915)

Sonata No. 2, Op. 19 (1898)

Andante

Presto

The Scriabin Piano Sonata-Fantasy No. 2 in G-sharp minor took the composer five years to write and was published in 1898. This alluring piece is in two movements and is particularly popular. The piece is widely appreciated and is one of Scriabin's most accessible pieces.

The programme note he wrote reads: 'The first section (Andante) represents the quiet of a southern night on the seashore; the development is the dark agitation of the deep, deep sea. The E major middle section shows caressing moonlight coming up after the first darkness of night. The second movement (Presto) represents the vast expanse of ocean in stormy agitation.'

The Andante was an impressionistic picture certainly but not as seductive and romantic perhaps as Scriabin might have wished. It is a balmy southern night after all. Expressively harmonic interpretation was present in the main but Scriabin always sought the sensually inaccessible, always seeking a dimension deeper. Gentleness and colour with a rather fluctuating dreamlike tone quality were present but there is something too focused in the sound she produces often for an evocation of painting or tender atmospheric ambience. Velvet touch, poetry with pianissimo moments is surely what we are searching for here...The Presto certainly gave one a painting of 'stormy agitation' on the vast ocean but the tempo and dynamic contrasts felt exaggerated on occasion and one simply marvelled at her extraordinary pianistic fluency and keyboard command rather than listen to the eloquent music and inspiring and passionate harmonic progressions and their emotional evocations.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810‒1849)

Andante spianato and Grande Polonaise Brillante in E flat major Op. 22 (1834-1835)

In the Andante spianato, Eydman was certainly ‘flowing and smooth’ with a beautiful rounded tone. Fine legato and cantabile. Chopin often used to perform this work as an isolated piece he loved it so much. She presented it understood as a nocturne and it was a lovely introduction although a little more poetry and sentiment may have been appropriate.

The essential nature of the style brilliant of which the Grand Polonaise Brillante is an essential and outstanding representative of Chopin’s early Varsovian style, seems rather a mystery to modern pianists outside of those living in Poland. Perhaps I am hopelessly wrong. Jan Kleczyński writes of this work: ‘There is no composition stamped with greater elegance, freedom and freshness’. The style involves a bright light touch and glistening tone, varied shimmering colours, supreme clarity of articulation, in fact much like what was referred to in French as the renowned jeu perlé. There are also vital expressive elements of charm, grace, taste and elegance.

One must not forget that Chopin astonished Vienna by his pianism but perhaps even more by the elegance of his princely appearance. The limpid, untroubled and joyful nature of the early polonaises, mazurkas, rondos, sets of variations on Polish themes and piano concertos were written in this virtuosic style brillant fashionable in Warsaw. Now decidedly out of fashion, this style was characterized by lightness, delicacy, charm, sonority, purity, precision and a rippling execution resembling pearls. These works could only have been composed in a state of happiness and youthful ‘sweet sorrows’ living in his native land.

The ‘call to the floor’ for the polonaise was a successful declamation or announcement dancing was about to begin, a touch of the martial spirit in evidence. This was an instrumental custom well understood by Chopin who in his youth was mad about dancing, a fine dancer and also an excellent dance pianist into the small hours hence his need for rehab at Bad Reinherz – now Dusznki Zdroj.

However this interpretation was not entirely the style brillante as I understand it. The many fiorituras were not always presented as decorative Venetian lace, the hand and touch rather too focused on bravura than cultured refinement, charm and affected elegance. Even though brilliantly performed, the work was somewhat stylistically inaccurate for me.

Her encore was a brilliant rather ostentatiously grand Études de Paganini No.2 in E- flat major by Liszt S.141

What a remarkable career this young lady has before her, the sunny uplands of pianistic fame

* * * * * * * * * *

Internet broadcast link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u_-spR-njC4

Wednesday August 11, 2021 20.00

Nikita MNDOYANTS

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

15 Variations and Fugue (Eroica Variations) for Piano in E flat major, Op. 35 (1802)

Most enjoyable and penetrating exposition of Beethoven's obsession with variation form, in particular with his favorite theme which of course appears in the Eroica Symphony and elsewhere. Fine command of the classical style. Each variation had its own character, timbre and personality (often rather rough hewn). The dramatic fugue was powerful and polyphonically characterful.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–49)

Ballade in F minor Op. 52 (1842–1843)

Penetrating the expressive core of the Chopin Ballades requires an understanding of the influence of a generalized view of the literary, musical and operatic balladic genres of the time. In the structure there are parallels with sonata form but Chopin basically invented an entirely new musical material. I have always felt it helpful to consider the Chopin Ballades as miniature operas being played out in absolute music, forever exercising one's musical imagination.

The brilliant Polish musicologist Mieczysław Tomaszewski describes the musical landscape of this work far more graphically than I ever could. The narration is marked, to an incomparably higher degree than in the previous ballades, with lyrical expression and reflectiveness [...] Its plot grows entangled, turns back and stops. As in the tale of Odysseus, mysterious, weird and fascinating episodes appear [...] at the climactic point in the balladic narration, it is impossible to find the right words. This explosion of passion and emotion, expressed through swaying passages and chords steeped in harmonic content, is unparalleled. Here, Chopin seems to surpass even himself. This is expression of ultimate power, without a hint of emphasis or pathos [...] For anyone who listens intently to this music, it becomes clear that there is no question of any anecdote, be it original or borrowed from literature. The music of this Ballade imitates nothing, illustrates nothing. It expresses a world that is experienced and represents a world that is possible, ideal and imagined.

Mndoyants gave

us a highly dramatic, chiaroscuro rather pianistic interpretation of the work. He

emphasized the strong narrative declamatory elements strongly and with emphatic passion.

The balladic tale twisted and turned, expressing that characteristic Polish

bitterness, passion and emotionally-laden disturbance of the psyche known

as żal. There could have been more contrast I felt between the incandescent anger and lyrical refection. What a monumental story of shifting realities is displayed

in this work!

This is a great opera of the human psyche and he concluded with a tempestuous coda to the work.

Il Cantastorie (The Ballad Singer) by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

INTERMISSION

Nikita MNDOYANTS (b. 1989)

Nocturne

It is well to be reminded that we seem to be modestly re-entering the world of composer pianists - Trifonov, Namoradze and Mndoyants to name only three. It opened with an exploration of sound and overtones, for the right hand alone. Reflective episodes follow also exploring what the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas referred to as 'the colour of saying.' A pianissimo left hand was punctuated by right hand crossing percussive harmonies. A nocturnal sleep with many disturbances of mind. Basically Mndoyants has created an impressionistic abstract sound world of freely associative meaning and great refinement. The work fades into the azure above us...

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Sonata No. 3 in F minor Op. 5 (1853)

Allegro maestoso

Andante espressivo

Scherzo. Allegro energico – Trio

Intermezzo. Andante molto

Finale. Allegro moderato ma rubato

|

| The young, handsome Johannes Brahms |

After his own work, the immense Brahms Sonata No.3 in F minor Op.5 (1853). Brahms composed this mighty sonata when he was barely 20 and when the sonata form itself was considered rather an outmoded. Of course Brahms idolized Beethoven and the personal expressiveness of his sonatas and perhaps was influenced by these grand conceptions. Brahms visited Schumann in Düsseldorf at the end of September 1853. Schumann was clearly overcome with admiration and wrote in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik :

“...sooner or

later … someone would and must appear, fated to give us the ideal expression of

times, one who would not gain his mastery by gradual stages, but rather spring

fully armed like Minerva from the head of Jove. And he has come, a young blood

at whose cradle graces and heroes mounted guard. His name is Johannes Brahms…”

Schumann was to commit suicide not long after in July 1856.

The young Brahms also met Berlioz at this time. In his role as inspired music critic, one can understand Schumann referring perceptively to the three early Brahms sonatas as veiled symphonies.

The massive opening spans the entire keyboard – it was almost as if an entire symphony orchestra had entered the Dworek. The Allegro maestoso was ‘majestic’ and a true Allegro rather than the Adagio maestoso many pianists adopt. The movement evolved with symphonic grandeur and noble passion. The essentially Romantic spirit of the sonata was clearly to be fused into a classical edifice, the architecture of which is truly awesome to behold over the approximately 40 minutes duration. He brought melodic sensitivity to the second Andante expressivo movement, but I was yearning for more of the poetry of love and heartfelt lyricism that culminates in the climax of passion. This is one of the greatest declarations of poetic love in music, the two lyrical themes merging symbolically into a passionate expression of sensual rapture. Brahms yearning for the 'impossible love' he felt for Clara Schumann ? The movement is prefaced by the Sternau poem:

The

evening dims

The moonlight

shines

There are

two hearts

That join

in love

And embrace in rapture

The third movement Scherzo was richly rhythmical. The introspective and mysterious Intermezzo. Andante molto with the term Rückblick (looking back) contained pregnant silences and recalled movingly at times elements of the previous three movements. The Finale. Allegro moderato ma rubato of this sonata with its orchestral sound palette, buoyant theme, captivating melodies, marches and pianistic fireworks was captured by Mndoyants with energy and powerful technique. By the end we were left with a finely honed conception of the stately architecture of this monumental work – one of the last great classical sonatas.

The tumultuous, enthusiastic reception of this performance was richly rewarded with four encores.

I. A refined and emotionally serene Siloti/Bach Sheep May Safely Graze BWV 208

II. Prokofiev 10 Pieces for Piano Op.12, Scherzo No.10 - a splendid account from this brilliant Prokofiev interpreter.

III. Rameau Les Sauvages from Nouvelles Suites de Pièces de Clavecin. Since Grigory Sokolov pioneered this composer on the piano in such spectacular and inimitable fashion, his works have crept into the encore repertoire

IV. Schubert Moment Musical in F minor Op.94 No.3 D780

A deeply rewarding recital from this brilliant artist.

* * * * * * * * * *

Internet broadcast link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GCxoyS3euJo

Wednesday August 11, 2021 4 p.m.

Nicolas Namoradze

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Contrapunctus VI, Die Kunst der Fuge BWV 1080 (1749)

This struck me from the outset as a most unusual programme design. The unfinished masterpiece of Bach's final years is an abstract demonstratio of the principles of contrapuntal composition. Bach suggests no instrumentation.

I cannot quite understand why Namoradze chose to open his recital with this work, inflicting such an isolated intellectual challenge on the public. The work is surely an intensely private internal dialogue between God and Bach the composer. Professor Wilfrid Mellers in his magnificent book Bach and the Dance of God considers it an angelic concourse 'intellectually sounds in the ears of God' - to use the 17th century polymath, Sir Thomas Browne's, phrase. In the 'late' works of Bach, archaic medieval elements are reborn and the rhetoric of opera fades away to be replaced by a variety of mathematical, 'logical' mysticism.

The performance of this isolated Contrapuntus had a distancing austerity in view of this, a type of willful human disconnection, the motivation hard for me to penetrate.

Nicolas Namoradze (b. 1992)

Études (selection, 2015–2017)

As his own austere polyphonic restless composition followed the Bach attacca, perhaps this explains this strange, immediate intellectual demands. His compositions are spectacularly effective and complex musical intellectual constructions in their way and require extraordinary transcendental keyboard command but apart from this demolishing sound effect what is the meaning of this music? I am not old-fashioned in the least and in my youth was deeply involved with the so-called avant-garde and 'New Music' - Stockhausen, Kagel, Xenakis, Pousseur, Boulez, Berio, Messaien, the Kontarsky brothers ... so I am quite open to adventurous and exploratory sound landscapes.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

Berceuse in D flat major Op. 57 (1844)

This was a pleasant enough performance but where did it fit into this programme, apart from all of us being resident in the Chopin shrine of Duszniki

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) / Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924)

Das Orgel Büchlein

Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ, Chorale prelude, BWV 639 (1708–1717)

The Bach chorales arranged by that magnificent composer Ferrucio Busoni are sublime to my mind. Here we were on more familiar expressive ground at least.

Franz Liszt (1811–1886)

Totentanz S.525

|

| The Dance of Death (1493) by Michael Wolgemut, from the Nuremberg Chronicle of Hartmann Schedel |

This was a work inspired by Liszt's obsession with death. In the spring of 1832 Paris was struck by cholera. Corpses in hessian sacks on carts were wheeled thought the city to the cemeteries. Riots broke out in overcrowded Père-Lachaise cemetery. Carts were overturned and fallen coffins burst open disgorging the putrefying contents. Liszt stayed in Paris during the epidemic. He used to visit the home of Victor Hugo where he played the Marche funèbre from the Beethoven Sonata in A-flat major 'while all the dead from cholera filed last to Notre Dame in their shrouds.' Liszt played the Dies Irae from dawn to dusk. It was in this dank and gloomy atmosphere he composed the Totentanz. The work, again best described by the Italian terribilità, was inspired by a fresco of the Last Judgement in Pisa.

Last Judgement fresco by Andrea Orcagna (now attributed to Buonamico Buffalmacco) in the Camposanto Monumental

We were given a pianistically impressive, rather intellectual performance of this work with much highlighting of the structural complexity I felt at the expense of the visceral horror that inspired Liszt.

Description of the Paris cholera epidemics

http://www.michael-moran.com/2020/03/chopin-in-time-of-cholera-paris.html

INTERMISSION

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Contrapunctus VII, Die Kunst der Fuge BWV 1080 (1749)

Felt rather similar to Contrapunctus VI described above.

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943)

Piano sonata No. 1 in D minor Op. 28 (1907)

Allegro moderato

Lento

Allegro molto

* * * * * * * * * *

Internet Broadcast link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c5knhtXcJ_g

Tuesday 10/08/2021 4 p.m.

Alexander KOBRIN

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Piano sonata in A flat major Op. 26 (1800–1801)

Andante con variazioni

Scherzo. Allegro molto

Marcia funebre sulla morte d’un eroe. Maestoso Andante

Allegro

This was the preferred sonata of Beethoven that Chopin appreciated greatly and used to teach. I would love to have heard Beethoven played in a style inescapably performed by the Polish composer à la Chopin, a reported experience of rare charm. Perhaps it was the funeral march in the third movement that attracted him.

I felt Kobrin was rather too classically detached emotionally from the intensely lyrical and poetic opening of the Andante con variazioni. However, he made the contrast between variations very attractive in terms of rhythm and character. I was yearning for more poetry than objectivity, but again this depends so much on how you personally conceive of the performance style of the early Beethoven piano sonatas.

The Scherzo. Allegro molto I found such an attractive contrast in mood and robust energy! In the Marcia funebre sulla morte d’un eroe. Maestoso Andante I could clearly hear a military element in the tympani and brass in the trio. I liked the forceful, pedantic, tragic tempo he adopted which was neither indulgently slow in the expression of grief nor too rapid to reflect deeply on the passing of a soul. In the Allegro he made much of the contrast between legato and detached sixteenth notes on which the movement hinges. Overall the sonata achieved an unaccustomed grandeur. The pianissimo 'abandonment' of the sound at the conclusion of he work, returning to the silence from which it emerged, was so metaphysically appropriate.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

Mazurkas Op.24 Nos 1-4

This set possessed a classical, poetic poise and simplicity rarely heard in Chopin mazurkas. I liked his approach of recalled pleasures a great deal.

Kazimierz Brodziński, whose lectures at the University of Warsaw were attended by Chopin, characterized the elegy genre (in his treatise O Elegii [On the elegy], from 1882) as follows: ‘An elegy conveys only tempered feelings: mirth, no longer present; sorrow, assuaged’. One might say that Chopin’s mazurkas adopted this idea.

No 1 in G minor is based on a kujawiak melody. No 2 in C major was more rustic and folkloric and based on the bucolic oberek. No 3 in A flat major is another simple dance melody on the kujawiak. The last, No 4 in B flat minor, is a justly renowned mazurka containing much nostalgia and Romanticism. The great Polish musicologist Mieczysław Tomaszewski wrote the most beautiful description of how this mazurka evolves organically. I could not possibly approach this quality of literary musical description so quote it for your delectation and edification:

'It begins with a two-part search for a path or a thread. The opening theme, of distinctly kujawiak provenance, is shaped before our eyes, freeing itself from constraint and hesitation before growing to its full sound and attaining a moment of ecstasy or delight. The complementary idea, unfolding in the bright key of the relative D flat major, brings a moment of amusement or play, scherzando, closer to salon waltzes than to country mazurkas. And then suddenly, in the midst of this swirling ballroom, sotto voce, like a voice from a distant world, we hear a purely folk melody, distinguished by its Lydian fourth, clearly discernible in the unison texture. Then another dance derived from a kujawiak melody, though a different melody than before. The swinging and swaying reaches a peak. But perhaps the most memorable part of all is the finale – or more properly the epilogue. At first we hear a soft phrase, cast out against changing chords supported by a single note that lasts insistently and endlessly. And then the music softens, falls and dwindles. The accompaniment stops. The phrase is heard for the last time in the utmost silence and solitude.'

Fantasy in F minor Op. 49 (1841)

A powerful and expressive performance certainly but seemed to lack a little the feeling of improvised fantasy playing like globes of mercury in the composer's mind, sometimes merging and sometimes autonomous but never controllable. This being said the account was fluent, effortless and authoritative as you might expect from such an accomplished artist. The devotionals and reflective chorale was most affectingly played followed by a passionate spontaneous eruption of emotion like a volcano of pent up energy released. There was a noble majesty in this performance, like a sculptor hewing a statue from granite.

INTERMISSION

Modest Mussorgsky (1839–1881)

Pictures at an Exhibition (1847)

This was without doubt one of the most remarkable, subtle and atmospheric performances of this much tormented work I have ever heard. Usually I prepare for the physical assault with dread. This was not the case with such artistic and superb painting in sound by Alexander Kobrin. The only comparable riveting and idiomatic account was by Denis Kozhukhin at Duszniki in 2010

Modest Mussorgsky by Victor Hartmann

This piece is a portrait of a man walking around an art exhibition (the pictures painted by Mussorgsky’s friend, the artist and architect Viktor Hartmann). The composer is reminiscing on this past friendship now suddenly and tragically cut short when the young artist died suddenly of an aneurysm. The visitor walks at a fairly regular pace but perhaps not always as his mood fluctuates between grief and elated remembrance of happy times spent together. The Russian critic Vladimir Stasov (1769-1848), to whom the work is dedicated, commented: 'In this piece Mussorgsky depicts himself "roving through the exhibition, now leisurely, now briskly in order to come close to a picture that had attracted his attention, and at times sadly, thinking of his departed friend.'

The Russian poet Arseny Goleníshchev-Kutúzov, who wrote the texts for Mussorgsky's two song cycles, wrote of its reception: There was no end to the enthusiasm shown by his devotees; but many of Mussorgsky's friends, on the other hand, and especially the comrade composers, were seriously puzzled and, listening to the 'novelty,' shook their heads in bewilderment. Naturally, Mussorgsky noticed their bewilderment and seemed to feel that he 'had gone too far.' He set the illustrations aside without even trying to publish them.