18th Chopin and His Europe Festival (Chopin i jego Europa) 14-31 August 2022, Warsaw, Poland

18th Chopin and His Europe Festival

14-31 August 2022

Warsaw, Poland

The Year of Polish Romanticism

This year, there will be over 30 concerts, and among them piano recitals by masters of piano, including Bruce Liu, the winner of the 2021 Chopin Competition. World-famous orchestras and chamber players will give as many as 16 concerts. We did not forget about vocal music: outstanding soloists will perform with recitals, and opera lovers will be given opportunity to listen to the concert performance of Un giorno di regno, ossia il finto Stanislao by Giuseppe Verdi.

Programme of the Festival in Detail

https://festiwal.nifc.pl/en/2022/kalendarium/

Most of the concerts of the Festival will be available to watch via free streams on the YouTube channel of The Fryderyk Chopin Institute. Selected concerts will also be broadcast by Polish Radio Channel 2 (Dwojka)

The programme book and extensive notes on musical works and musicological essays by renowned experts in the field is remarkable in itself.

|

View of Warsaw from the Terrace of the Royal Castle by Bernardo Bellotto (1722-1780) called Canaletto from the collection of the National Museum. Photo: National Museum in Warsaw |

Introduction to this Extraordinary Festival

unique in its European scope

by

Stanisław Leszczyński

Artistic Director

The 18th Chopin and His Europe Festival will open with three great artists of Polish Romanticism: Chopin, Mickiewicz and Moniuszko. At the outset, we will hear Widma by Stanisław Moniuszko, a cantata which is a musical version of the second part of Dziady. It is a very clear gesture towards this epoch – rather special for our Polish culture and celebrated this year.

The work,

created in the mid-19th century, is an example of the fascination with the text

by Mickiewicz, the essence of the Polish interpretation of Romanticism, its realization

in non-existing, but vivid national identity of Poles – both in Polish lands

and in exile. It exemplifies force and longing, it brings mystery and an

element of mysticism, originating from traditional ritualism. But primarily, Widma,

tells a story of one of the iconic texts of Polish literature (and at the same

time one of the most distinctive Polish Romantic texts) with great music. The

work is a priceless treasure of Polish cultural heritage.

In August

2022 this work will be performed, together with another cantata by Moniuszko, Nijoła,

under the baton of Fabio Biondi, who – fascinated by this composition –

is shocked how Moniuszko remains a greatly underappreciated artist on international

stages and in the concert halls of Europe. After the enthusiastic reception of his

operas, he will perform and record Widma and Nijoła with the

soloists of the Podlasie Opera and the Philharmonic Choir and the

Europa Galante Orchestra.

There will be much more Moniuszko in the festival programme: we have planned

two concerts with his songs, performed by Olga Pasiecznik with Ewa

Pobłocka, Mariusz Godlewski with Radosław Kurek (both as part

of the promotion of The Institute’s new records) and Dorothee Mields

with Tobias Koch; a very interesting element connected with Moniuszko

will be also present in the programme with the concerts by the Royal

Philharmonic Orchestra, performing the Overture to Paria, and Sinfonia

Varsovia, which is going to perform Moniuszko’s Pearls by Zygmunt

Noskowski, i.e. symphonic orchestrations of Moniuszko’s songs.

The programme axis of the Festival is traditionally based on

the music of Fryderyk Chopin whose work is the essence of Polish

Romanticism, emotionally being its essence. His works will be performed by

outstanding pianists and great ensembles on contemporary and historical

instruments; there will be fascinating contexts as well. Etudes and Nocturnes

will be interpreted by Jan Lisiecki, Preludes by Aimi

Kobayashi, Bruce Liu will perform the ‘La ci darem la mano’ Variations from

Don Giovanni, which were so enthusiastically reviewed during the

Competition and – together with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under

the baton Vasily Petrenko – the Concerto in F minor Op.21. The Concerto

in F minor Op.21will also be performed by Kate Liu, but also… for

the first time in the version for guitar, by Mateusz Kowalski and the Collegium

1704 under Vaclav Luks. Cyprien Katsaris will present works

by friends and pupils of Chopin together with extensive fragments of Don

Giovanni by Mozart arranged by Bizet, recorded in a complete version for

The Fryderyk Chopin Institute. We will also hear – performed by the Orchestra

of the Polish National Philharmonic under the direction of Andrzej

Boreyko – Fuego Fatuo by Manuel de Falla, a work for the stage

entirely based on orchestrated music by Chopin. The piano concerto by Andrzej

Panufnik will find a new interpretation by Alexander Gadjiev. The Beethoven

Academy Orchestra under Jean-Luc Tingaud will perform works by

E.T.A. Hoffmann, Cesar Franck and Feliks Nowowiejski. And these are only

selected fragments of the rich programme…

Undoubtedly, everyone – the audience as well as we, the organisers – is waiting

for the performances of the most interesting personalities of last year’s

Chopin Competition, the new elite of world pianism. In addition to the already

mentioned winner Bruce Liu, Alexander Gadjiev and Aimi Kobayashi,

there will be performances by Kyohei Sorita, Martin Garcia Garcia, Leonora

Armellini, Jakub Kuszlik and J J Jun Li Bui – all with highly

interesting programmes, featuring, in addition to Chopin, Beethoven, Bach,

Debussy, Rameau, Liszt... We will also welcome the 2010 winner, Yulianna

Avdeeva, and the talented Ukrainian pianist Dinara Klinton. Alim

Beisembayev, the winner of last year’s piano competition in Leeds, will also

perform – for the first time at the Festival.

Other highlights of the Festival will certainly be the concerts by Maria

Joao Pires (with the Basel Chamber Orchestra conducted by Trevor

Pinnock) and the European Union Youth Orchestra conducted by Gianandrea

Noseda and Francesco Piemontesi as well as performances by the Belcea

Quartet (together and separately) and the Apollon Musagète Quartet...

The magical world of authentic sound and ‘historically

informed’ musical interpretation will be brought to us this year by pianists Kristian

Bezuidenhout, Tobias Koch, Dmitry Ablogin, Tomasz Ritter, Aleksandra Świgut,

clarinetists long associated with the Festival: Lorenzo Coppola and Eric

Hoeprich as well as violinists Alena Baeva and Chouchane

Siranossian. Internationally renowned orchestras will play: our leading

ensemble of historical performance, {oh!} Orkiestra Historyczna, Europa

Galante, Collegium 1704 and – in a very special way – the Orchestra of

the Eighteenth Century, which has accompanied the Festival since its first

edition. We will hear Henryk Wieniawski’s Concerto in F-sharp minor and

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major in its original

version, with Jan Lisiecki sitting at the historic piano for the first

time.

And a few words about Polish music, especially one that is still little recognized,

the best presentation of which is always our mission and a privilege at the

same time. This year, the programme will focus on Polish Romanticism: Józef

Władysław Krogulski’s Miserere (Collegium 1704), Karol

Kurpiński’s Clarinet Concerto (reconstructed in a different way than

last year, this time interpreted by Eric Hoeprich and The Orchestra

of the Eighteenth Century), August Fryderyk Duranowski’s Violin Concerto

and Ignacy Feliks Dobrzyński’s Duo for Clarinet and Piano. There will

also be Romantic music from Germany (Winterreise with Matthias Goerne

and Leif Ove Andsnes), France (Gounod and Franck, whose 200th anniversary

of his birth is celebrated this year), the Czech Republic (Reicha, Dvorak),

Scandinavia (Sibelius) and England (Elgar).

As part of this year’s edition of the Festival, over 30 concerts are planned to

take place in the most important halls of Warsaw. We hope that this time the

pandemic will not limit the number of the viewers and listeners that we can

invite for the events. Regardless, most of the concerts will be streamed and

broadcast by Channel 2 of Polish Radio.

The Fryderyk Chopin Institute

Reviews

Photographs by Bartek Barczyk

Final Symphonic Concert of the Festival

The hall was excitedly overflowing to capacity on this much anticipated final concert

31.08.22

Wednesday

20:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Performers:

Bruce (Xiaoyu) Liu piano

Vasily Petrenko conductor

Stanisław

Moniuszko

Overture to the opera "Paria" ('Pariah' - The Outcast)

In this performance of an outstanding Overture, the drama was highlighted from the outset. Petrenko is a visionary musician and presented us with passionate writing of anguished social exclusion. Solitary soloists played as if individual voices in the opera. However, I could not help reflecting on the complete absence of any Indian 'flavour' to the music! Charming solo passages, unashamedly cosmopolitan, followed depiction of the severe social drama and harassment of being deemed a 'pariah' in traditional Indian society. This faultless construction of the piece was clear from its ideal length and the balance maintained between drama and lyricism.

I offer some

insight into this fascinating but unaccountably neglected opera.

The year 2019 was the 200th anniversary of the birth of Stanisław Moniuszko (1819-1872), the greatest operatic composer in nineteenth century Poland. There were musical celebrations throughout country and the resuscitation of his long forgotten works in performance. The seemingly impossible dream of the independence of the country as a sovereign nation and accession to the European Union means that at last what one might term the 'Cultural Iron Curtain' has been split apart to reveal formerly unknown artistic treasures of this valiant nation to the wider European continent. In no domain has this been more obvious than in music, but also in art, architecture, theatre and literature. The Polish language does present a difficult barrier in a way that English, French and Italian do not in the West. This remark does not assume a forest of undiscovered composers of genius, but certainly many of enormous talent and significant musical gifts to augment the European musical canon.

|

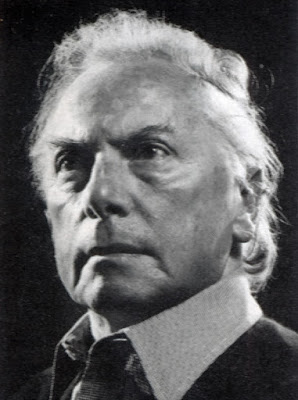

| Stanisław Moniuszko (1819-1872) |

Perhaps now as a result of this fiercely competitive vocal competition (which is mounted every three years), this fine composer and his works will reach a wider more international audience.

Piano Concerto in F minor Op. 21

Bruce Liu,

the piano soloist in the concerto, was the First prize-winning pianist from the

18th International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 2021. As a

result this concert was highly anticipated and sold out. He chose to play the

Chopin F minor concerto, the first written by

the composer. The issue of 'When written?' between Chopin's two concerti is not

of the greatest chronological significance as Chopin’s two piano concertos

were composed within a year of each other. I am always amazed at the nature of

true genius, as the F minor was written when Chopin was in his late teens.

Perhaps this is why such fine performances are often during the International

Chopin Piano Competitions in Warsaw when performed by young pianists of much

the same age as the composer. After the competition, familiarity seems to

dull the youthful burnish given them by rivalry.

The concerto

follows the Mozart model and was directly influenced by the style

brillante of Hummel, Kalkbrenner, Moscheles or Ries. It is hard to

reproduce this intimate yet fragile glittering tone on a Steinway but I felt

tonally Liu managed this internally iridescent style with floodlit

brilliance. In this early work Chopin magically transforms the Classical into

the Romantic style.

‘As I already have, perhaps unfortunately, my ideal, whom I faithfully serve, without having spoken to her for half a year already, of whom I dream, in remembrance of whom was created the adagio of my concerto’ (Chopin to his friend Tytus Woyciechowski, 3 October 1829).

The work itself was written 1829-30. As we all know by now, this concerto was inspired by Chopin’s infatuation, or was it youthful love, for the soprano Konstancja Gładkowska. Strangely it was published a few years later with a dedication to Delfina Potocka.

Liu's conception, performance and understanding

of the styl brillant was evident in the opening Maestoso movement

and the Polish rhetorical gestures concealed within the work were well

delineated. I felt that Liu added much youthful, curiously coalesced, emotional

expression to the writing. He also brought enviable variation of dynamic, tone

and touch. Oddly and most surprisingly, considering their experience of this work, the orchestra and conducting were rather unsubtle and conventional.

However, the Larghetto love song was moving and sensitively nuanced. The stream of consciousness Chopin offers us flowered in all the illusioned beauty of youth before the fissures of experience begin to deeply line the face. The movement was full of considered poetry and lyricism. At moments, however, the forceful, more passionate aspects of this watercolor of shifting moods lacked proportion and emerged inappropriately exaggerated. The anger and frustration Chopin depicts is not that of the formed, experienced adult but that of an adolescent psyche aching to realize an unknown degree of romantic recognition and consummation.

Arguably the Larghetto is

the most beautiful love song ever written for piano and orchestra. The

unrequited love Chopin treasured for the soprano and fellow pupil Konstancja Gładkowska, that yearning he

was forced to 'enjoy' at inaccessible psychological and physical distance,

produced poignant, lyrical melodies of an intense order. At times the reflective music is of moths fluttering at dusk, the movement of the aroused heart in its

yearning for 'mon amour'. As can be the way in life, it is said she

preferred the attentions of the handsome Russian officers in splendid

uniforms to our poetic genius!

Jean Sibelius

Symphony No. 2 in D Major Op. 43

30.08.22

Tuesday

20:30

Warsaw

Philharmonic Concert Hall

Symphonic Concert

Performers:

Corina Belcea violin

Axel Schacher violin

Krzysztof Chorzelski viola

Antoine

Lederlin cello

Andrzej Boreyko conductor

Program:

A most unusual programme to be sure but with a predominantly English flavour

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

Double concerto for violin and viola (1932)

This rarely performed work in short score was completed by the brilliant 18-year-old RCM student Benjamin Britten by early autumn of 1932. In the summer of that year he also composed his Op. 1, the dazzling Sinfonietta for ten instruments. I had never heard the work before.

Compositions for violin, viola and orchestra in the classical music repertoire are uncommon pace the Sinfonia Concertante of Mozart. Britten’s concerto has clearly been formally influenced by this work in a performance of the work that Britten had written as being ‘the most marvellous musical thrill of my life yet’. Another influence is possibly Walton’s Viola Concerto, which he had admired on another occasion.

There are three movements in the Double Concerto:

1 Allegro

ma non troppo

2

Rhapsody: Poco lento

3 Allegro scherzando – Tempo primo (Allegro ma non troppo)

The first movement, completed in two days, has interesting and rather exotic orchestration. The soloists are dominated by brass and timpani with a heartbreaking and yearning violin solo. Britten was however already displeased with the work saying he had written a ‘fatuous’ slow movement, and that ‘I shall tear that up soon’. Needless to say the work soon fell into obscurity.

The concerto survived in short score, and was prepared for performance by Colin Matthews, who noted that it was ‘complete in practically every detail’. It was performed complete for the first time in the 1995 Aldeburgh Festival, and recorded by the conductor Kent Nagano with Gidon Kremer and Yuri Bashmet as soloists. It is a lively piece that possesses fine melodic lines and dense dialogue between the soloists. John Bridcut, the English documentary filmmaker of works concerning Britten, observed ‘Britten’s true orchestral personality flowers for the first time’.

In the Rhapsody:

Poco lento we were presented with a melancholic flight on the solo violin,

a bird transcending the azure. I found the string writing almost neurotic in

its agitation. The double bass was as if the heart was pumping blood and

hovering over the strings. The texture was quite extraordinary with kettledrums

and flutes. As we moved into the final inventive final movement, power and

momentum began to build. I heard folk music elements and huge dynamic

contrasts were rendered in the percussion and timpani.

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Double Concerto in A minor for violin, cello and orchestra Op. 10 (1887)

Orrin Howard writes illuminatingly in a programme note for the LA Philharmonic of the immensely personal gestation of this piece.

Although Brahms lived for twelve years after completing his Symphony No. 4 in 1885, he produced only one more orchestral work, and that one not a symphony but a concerto. And no ordinary solo concerto, either, but rather a composition which united for the first time in the form the violin and cello.

Why a concerto for this unusual combination? It has been ventured that the work was meant as a peace offering to the composer’s dear, but at-the-time alienated friend, violinist Joseph Joachim, understandably hurt that a letter of Brahms which was sympathetic to Joachim’s wife was brought as evidence in the couple’s divorce proceedings. When their mutual friend, cellist Robert Hausmann, asked Brahms for a concerto in 1887, the composer apparently saw a way to satisfy the cellist and win back the friendship of the violinist. Brahms’ instincts were right. Joachim was receptive to Brahms’ concerto overtures, and after Joachim, Hausmann, and Brahms had tried out the piece for friends, Clara Schumann wrote in her diary, “The Concerto is a work of reconciliation. Joachim and Brahms have spoken to one another again.”

The Allegro had a majestic yet vehement opening with significantly oceanic forces at the conductor's command. The rich Lederlin cello solo was in elevated dialogue with the superb Belcea violin, eloquent echoes of each other. The cantabile on the cello was deeply moving in this magnificently rhapsodic music. The inspirational Brahms melodies in the hands of these expressive soloists was both masculine in nature and powerful in impact. The immense experience in orchestral writing that Brahms had accumulated by this period in his life was overwhelmingly persuasive.

The Andante opened with a sublime melody which convincingly emanated directly from the heart and what a poignant heart it had become. Such a love song lies here it prompted me to sing in ardent devotion myself. The cello was profoundly eloquent in its emotional weight in this magnificent movement.

The Vivace has a fabled theme for excellent reasons. The duo of

violin and cello are here in inspired melodic symbiosis. One must also mention

the outstanding orchestral soloists who have been infected by the high-flown

musical sentiments that filled us all with devotion and romantic elevation,

lifting us out of the mundane and depressingly brutal reality of our times.

Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Introduction and allegro for string quartet and orchestra Op. 47 (1905)

The Introduction and Allegro was suggested to Elgar by August Jaeger -the Nimrod of the Enigma Variations - who suggested that he compose something for the recently founded London Symphony Orchestra. He described 'a brilliant, quick scherzo' which Elgar took to heart.

Elgar composed by writing themes in a sketch book as they came to him, even if he did not immediately use them. The Introduction and Allegro contains what Elgar referred to as the 'Welsh tune'. It had been plated in his mind in August 1901 when the Elgars were on holiday in Cardiganshire, West Wales. Folk tunes may have inspired it.

The work was not an instant success and took to achieve its present popularity. Perhaps the string virtuoso requirements dissuaded performances.

This performance was poignant yet grand and the fugal polyphony quite brilliantly handled.

Unusually the four soloists of the Belcea Quartet gave an encore at this point in the concert despite it not being actually complete. They played a desperately moving account of the Cavatina from the Beethoven String Quartet No. 13 in B♭ major, Op.130, dedicating it to tortured Ukraine.

Mark Steinberg writes movingly and poetically of this movement in a note for the Brentano Quartet:

'Beethoven’s Cavatina indeed deals with the folly of human conceits, the frailty and vulnerability of our love and our tenuous ability to communicate it, indeed our deep lack of any true model of our inner states. And it touches on the richness of the human capacity for love as well as the loneliness of isolation in the chasm between feeling and expression.'

Of one passage he writes: 'The gap in expression is palpable. The incongruity of the utterances opens a space for one of the most unsettling passages in all of music, with the first violin left in desperate isolation. Beethoven marks the passage beklemmt: oppressed, anguished, stifled.' [...] 'Exquisite paradox: Music is inadequate to express what pleads to be expressed; this failure is flawlessly expressed by music.'

The inner pulsation put me in mind of irrepressible human heartbeat. In view of the present barbarous horrors meted out on the innocent people of that benighted country, I was moved as never before.

Edward Elgar

Variations on his own theme "Enigma" Op. 36 (1899)

The performance of this work at this point of spiritual anguish was a welcome balm. Anecdotally, Elgar, after returning from giving debilitating violin lessons, relaxed into an improvisation at the piano. His wife, Caroline Alice, Lady Elgar, thought one melody had distinct possibilities. Elgar wondered aloud how various friends of theirs might envisage it. Miraculously emerged the concept of the Enigma Variations, the work that established Elgar as a serious national and international composer of note.

In all, fourteen people and that most British of gifts, a dog, are featured in the variations:

First

Variation - C.A.E.

Elgar's wife, Alice, lovingly portrayed

Second

Variation - H.D.S-P.

Hew David Steuart-Powell,

a pianist with whom Elgar played in chamber ensembles

Third

Variation - R.B.T.

Richard

Baxter Townshend, a friend whose caricature of an old man in an amateur theatre

production is captured in the variation

Fourth

Variation - W.M.B.

William Meath

Baker, 'country squire, gentleman and scholar', informing his guests of the

day's arrangements

|

| The Leaping Horse (1825) by John Constable (1776-1837) |

Fifth

Variation - R.P.A.

Richard

Arnold, son of the poet Matthew Arnold

Sixth

Variation - Ysobel

Isabel

Fitton, an amateur viola player from a musical family living in Malvern

Seventh

Variation - Troyte

Arthur Troyte

Griffith, a Malvern architect and close friend of Elgar throughout their lives

- the variation focuses on Troyte's limited abilities as a pianist

Eighth

Variation - W.N.:

Winifred Norbury,

known to Elgar through her association with the Worcestershire Philharmonic

Society - the variation captures both her laugh and the atmosphere of her

eighteenth century house

|

| The Hay Wain (1821) by John Constable (1776-1837) |

Ninth Variation - Nimrod

A J Jaeger,

Elgar's great friend whose encouragement did much to keep Elgar going during

the period when he was struggling to secure a lasting reputation - the

variation allegedly captures a discussion between them on Beethoven's slow

movements

Tenth

Variation - Dorabella

Dora Penney,

daughter of the Rector of Wolverhampton and a close friend of the Elgars

Eleventh

Variation - G.R.S.

George

Sinclair, organist at Hereford Cathedral, although the variation allegedly

portrays Sinclair's bulldog Dan paddling in the River Wye after falling in

Twelfth

Variation - B.G.N.

Basil

Nevinson, an amateur cellist who, with Elgar and Hew Steuart-Powell, completed

the chamber music trio

Thirteenth

Variation - ***

probably Lady Mary Lygon, a local noblewoman who sailed for Australia at about the time Elgar wrote the variation, which quotes from Mendelssohn's Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage. The use of asterisks rather than initials has however invited speculation that they conceal the identity of Helen Weaver, Elgar's fiancée for eighteen months in 1883/84 before she emigrated to New Zealand

Fourteenth

Variation - E.D.U.

Elgar himself, Edoo being Alice's pet name for him.

There are two enigmas and some mysteries underlying the variations. The variations are the most widely performed of all Elgar's works while the ninth variation - Nimrod - is arguably the most moving and best loved excerpt in the whole of the classical repertoire. During my long career as a lecturer in British cultural studies, I often played Nimrod to accompany paintings by John Constable, Turner and Gainborough as well as the great English country houses of say Longleat and Blenheim and the landscaped gardens of Stourhead and Rousham.

Here was a fine, spirited, musically enlightened and at times moving performance of an iconic British symphonic work by Edward Elgar - the Warsaw Philharmonic under Andrzej Boreyko.

30.08.22

Tuesday

17:00

Warsaw

Philharmonic Concert Hall

Symphonic

Concert

Performers:

Maria João Pires piano

Trevor Pinnock conductor

Program:

Maurice Ravel

Le tombeau de Couperin

This work is poignant for me (being both harpsichordist and pianist). I remember graphically the leading role Trevor played in the revival of so-called 'Early Music' in London in to 1970s. His early vinyl recordings of Rameau keyboard works remain unequaled in their energetic drive, detail and refinement. These profound musical qualities now enhance and inspire his conducting.

In Le Tombeau de Couperin each movement of the Baroque style suite dedicated to friends massacred in the fetid horrors and stinking trenches of the Great War. Such a contrast within human nature is laid out for us. 'The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence' he commented in response to criticism.

The music of Francois Couperin has always remained for me one of the great touchstones of a high point in human creative civilization. I play a great deal of it on the harpsichord. In this work Ravel fused his modern sensibility with the expressive gestures of 18th century France. He described the suite 'directed less in fact to Couperin himself than to French music of the 18th century.' Ravel melded rhythmic, melodic and cadential forms of the time of Couperin with modern times. The work expresses the present through the mirror of the past.

The elegance of the composer is surely expressed in the graphics of the cover Ravel designed for the keyboard version of the music himself. The work was originally written for piano (1914-1917).

I

Prélude In memory of First Lieutenant Jacques Charlot

(transcriber of Ma mère l'oye for piano solo)

II

Fugue In memory of Second Lieutenant Jean Cruppi (to whose mother, Louise

Cruppi, Ravel had also dedicated L'heure espagnole)

III

Forlane In memory of First Lieutenant

Gabriel Deluc (a Basque painter from Saint-Jean-de-Luz)

IV

Rigaudon In memory of Pierre and Pascal Gaudin (two brothers and childhood

friends of Ravel, killed by the same shell in November 1914)

V

Menuet In memory of

Jean Dreyfus (at whose home Ravel recuperated after he was demobilized)

VI

Toccata In memory of Captain Joseph de Marliave (musicologist and husband of Marguerite Long)

|

The orchestral version we heard this evening was arranged by Ravel in 1919, by ut only four movements as he regarded the final two as too pianistic (Prélude, Forlane, Menuet and Rigaudon). As there have been many other orchestrations of this work I was rather unsure which version we were listening to. I found the whole work charming melodically and the energetic dance rhythms exciting under Trevor Pinnock. Many orchestral soloists were outstanding such as the lyrical and poetic oboist.

|

The inscription reads: Familiar with Lyons and its forest, Maurice Ravel composed in this house 'Le Tombeau de Couperin' (1917) and orchestrated here the 'Pictures at an Exhibition' suite (1922) Lyons-la-Forêt, Eure, Normandie, Franc Maria João Pires piano Trevor Pinnock conductor Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto in A major, K. 488 (1786)

This concerto was among three that Mozart offered to Sebastian Winter in a letter to Prince von Fürstenberg for the use of the court orchestra at Donaueschingen. It is doubtful it was ever performed in Vienna as few people knew of it, unlike many of his other concertos. Such vivid charm, expressiveness, nuance and musical refinement lie in this magnificent work, sublime in its simplicity of structure.

In the opening Allegro Pires immediately expressed a glowing tone and refined touch, two qualities for which she is renowned and illuminate her Chopin playing. She maintained an intimate and close connection with both conductor and orchestra during the blithe, enchanting and lively phrases of this straightforward movement, brimming as it does with refinement and bon goût. Stylish yet restrained. Her cadenza for the first movement was finely phrased, elegant and graceful yet not lacking in internal energy. The Adagio brought me close to tears. This is one of the most poignant movements Mozart ever wrote for the piano. He expresses from deep within and extremely soulful and heartfelt yearning for love or anguish over the loss of it. Her phrasing was superb in the expressive manner of an operatic aria. F sharp minor is my favourite key which always rends my heart with its tragic tonality. It is the only concerto movement he wrote in this dark key. The movement was divine in its sensitivity and tragic, emotional desire – such a moment of heightened existence and meditative thought during the travails of life. The orchestral support was subtle and delicate, luminous to the soul. The tragic mood is all pervasive – simple yet profound in depth – one of the great utterances of Western civilization on the nature of mortality, despair and grief. The clouds of melancholy are dispersed with the winds in the Allegro assai. Pires Pinnock and the orchestra brought such a rush of welcome joy and refined elegance to this movement. A life enhancing return to life. The piano confines itself here to elaborating orchestral themes and detail. There was exquisite orchestral detail within the ensemble which led to a complete symbiosis of soloist and orchestra. Perfect intonation in the strings and as if the dynamics were wrapped in velvet. The movement was simply a delight of panache felt during the Viennese course of life, not being 'too serious’ as the inevitable obstacles to human happiness arise. Her control of variation in dynamics evoked a kaleidoscope of colours drawn from the instrument with style, panache and élan. No phrase was repeated in the same manner of articulation. The movement blows away the moody old clouds with supremely effective intention and energy. Kohlmarket Vienna 1786

A deeply satisfying performance if occasionally lacking in spontaneous creative gestures in real time which gave the impression of slight over-familiarity with this score. Charles-François

Gounod (1818-1893)

Symphony No.2 in E-flat major (1855) The French temperament is not conducive to mahogany philosophical speculation or disturbing metaphysics. Perhaps this is the reason the nineteenth century French symphony is not riding high in the expressive heavens. The Symphonie fantastique of Berlioz in 1830 had scarcely any progeny. Although the composer Gounoud is beloved and popular as an operatic composer, I find his orchestral music rather undistinguished on any spiritual and philosophical level. I felt in some ways this finely wrought symphony was akin to the raising of Lazarus - a miracle certainly but not an attractive proposition The opening Adagio - Allegro agitato was tuneful but for me not much more than this in its implications. I could, however, feel Beethoven's Eroica lurking in the shadows. The Larghetto ma non troppo failed to touch my heart with its melodies although the orchestra has a finely honed sound which touches the emotions given the most evocative music. Charming French melodies fell gracefully on the ear but for me a symphony must have a degree of metaphysical depth and existentialist angst. The alluring melodies fly like the birds and butterflies. The Scherzo. Allegro molto was not as exciting as I had hoped but the extraordinary musical cohesiveness of this orchestra was well in evidence. The memorable tunes remain just that, memorable and joyful. The Finale. Allegro leggiero assai danced along with a delightfully light French touch. Clearly this symphony is a fluent musical composition but ....

The orchestra are a remarkably self-disciplined ensemble. As an encore they performed La Poule by Rameau arranged for orchestra. This was a truly marvellously galvanizing arrangement and fabulously executed. |

29.08.22

Monday

18:00

Royal Castle Concert

Hall

Chamber concert

Performers:

Lorenzo Coppola - clarinet

Christina Esclapez - historical piano

Ignacy Feliks

Dobrzyński

|

| Ignacy Feliks Dobrzyński (1807 -1867) |

The Polish

composer and teacher of Fryderyk Chopin, Jozef Elsner (1769-1854), had another

pupil of near genius (if I may be so bold) Ignacy Feliks Dobrzyński,

a school friend of Chopin. Elsner wrote in a report of Chopin 'special ability

- Genius etc' and of Dobrzyński 'rare ability'.

Unlike

Frycek, he came from a professional musical family and was in many ways

more precocious and wider in orchestral instrumental adventurism and

skill than Chopin who concentrated so single-mindedly on the piano as a

vehicle for his expressive soul. Many of his fine works are being

resuscitated in Poland during this Polish musical renaissance, especially

his symphonies, cantatas, songs, chamber works, a piano concerto, piano pieces

and perhaps in the future, his opera Monbar. His first

published work, a Polonaise in A major, was dedicated to

the Polish pianist Maria Szymanowska. When Chopin left Warsaw for

Paris on the eve of the November Uprising of 1830, avoiding

the brutal Russian occupation, the Polish composer Ignacy

Feliks Dobrzyński stayed on and satisfied the intense demand for

patriotic music. He seems condemned to labour under the cloud of his

compatriot of genius, Fryderyk Chopin.

Duo in A-flat major for clarinet

and piano (1847)

This was one of his last works in the chamber music genre, composed in the 1840s. It was first performed in 1853 but not published for a hundred years. The Buchholtz copy piano (a Polish manufacturer from Chopin's day) and clarinet (a copy of a period 1820 instrument) were well matched in timbre and sound texture.

|

| The keyboard of the Buchholtz piano |

Coppola gave his highly entertaining and knowledgeable introduction to the work, indicating the significant influence of opera in its composition.

The Agitato opening movement clearly has an operatic aria base with the male and female 'voices' (piano and clarinet) of the duo 'arguing' in lively arabesques. There are touches of militarism in the march theme. The Adagio doloroso and molto espressivo opened with an extraordinary dark 'rumbling' cloud of sound from the piano with the clarinet floating above this threatening sea like a soaring bird. Charming, melodic and effective. The final Allegretto mosso e animato features a blithe melody on the clarinet. Again we eavesdrop on a 'conversation' between piano and clarinet. Esclapez rendered the piano most attractively, semi-detaché articulation with a singing melody. There is much humour, charming wit and the carefree joy of youth in this music.

Ballade in B

minor, No. 2 (S. 171) (1853)

|

| The Paul McNulty copy of the piano by the great Viennese maker Johann Baptist Streicher (1796–1871) |

Esclapez chose an 1868 piano by

the great Viennese maker Johann Baptist Streicher (1796–1871). She

loved the colours, timbre and sound of this instrument a great deal.

Hero and Leander (1798) by Jean-Joseph Taillasson (1745-1809)

The distinguished

pianist Claudio Arrau was a student of the Liszt pupil Martin Krause. His

embedded tale is of the lovers Hero and Leander who lived separated by the

Hellespont. Each evening Hero would light a lamp and Leander would swim to him

and gather in the oblivion of love. However one stormy night the lamp was blown

out and Leander lost his way in the pitch black of night and cold waters. In

the morning light Hero spied the body of her beloved Leander dead on the shore.

In despair she committed suicide. The music of the Ballade clarifies this

myth and the scenes leading up to the tragic drowning are aesthetically and

poetically depicted.

The refinement of touch by

Esclapez extracted a superb colour spectrum from the different registers of

this instrument. The evocation of love in the theme was both lyrical and

aesthetically beautiful. She created an 'oceanic' sound from the Streicher, a

feeling of storm tossed emotional seas. The contrast of registers in sound,

textural exploration, was like a beacon had suddenly been illuminated on

a dark night. One had a profound expression of tragic events not unlike a

Chopin Ballade but more 'programmatic' in the best sense.

It is clear that Liszt had studied the structure and emotional landscape and its development in the Chopin Ballades (often the lineaments of a coherent dream realized in sound). He, in fact, dedicated this work to Chopin. However, in some ways he distanced himself from the Chopin form and liberated it. Obsessed with literature, as so many nineteenth century composers were, he was obviously aware of written folk and poetic literary ballads. He made a definite contribution to and development of the genre in this work.

Esclapez wonderfully did not present

it as simply another large, predominantly virtuoso work by Liszt, but rather as

a narrative poem of many scenes. In many ways Liszt opened up new musical avenues

to explore by later composers although the Ballade he wrote has few direct imitators it such a daunting

keyboard masterpiece.

|

| The Paul McNulty copy of the 1868 Johann Streicher piano |

Johann

Baptiste Streicher (1796 — 1871) was the son of Nanette Stein and Johann

Andreas Streicher. He was part of a piano making dynasty, already one hundred

years famous in 1870, when the Streicher company gave Brahms a grand piano

(Serial No. 6713, manufactured in 1868), which he used for the rest of his

life.

Brahms

described his relation to his piano in a letter to Clara Schumann: “It is quite

a different matter to write for instruments whose characteristics and sound one

only incidentally has in one’s head and which one can only hear mentally, than

to write for an instrument which one knows through and through, as I know this

piano. There I always know exactly what I write and why I write one way or

another.” He also advised her, in another letter, to buy a Streicher. When

Clara Schumann visited Johannes Brahms for the last time in 1896, together with

her children, they gathered in his apartment around his Streicher piano, and

she played, reading through his latest, probably intermezzos, with tears

streaming down her cheeks.

This

particular instrument realizes a beautiful, confident design from a unique

dynasty in piano building. The impulse to reproduce Brahms’s favourite piano

came from prominent Australian Professor Neal Peres da Costa, the author of

“Off the Record: Performing Practices in Romantic Piano Playing” – Oxford University Press. The project was hugely aided by Paul McNulty’s owning two contemporaneous

pianos, opp.6747 and 6932, which functioned as a priceless technical resource,

controlling every feature of construction and refinement (taken from the Paul McNulty fortepiano website).

Clarinet Quintet in

B minor Op. 115 (arrangement by Paul Klengel for clarinet and piano)

This

transcription of the 'heavenly' quintet for piano duo was made in 1892 by Paul

Klengel (1854-1935). He was a violinist, pianist and conductor at the Leipzig

Conservatoire. Amazingly, it was only rediscovered a few months ago when a private

music collection was donated to the library of the Haute école de musique

in Geneva.

Esclapez once

again chose the Streicher piano and Coppola played a copy of a clarinet originally

used by the inspired clarinetist friend of Brahms, Richard Mühlfeld.

The opening Allegro was brimming with colours, timbre and many variations in dynamic. The clarinet sculpted flowing arabesques of melody. The Adagio was most affecting in its lyrical theme which was transformed into a rhapsodic mood at times. The colours that Coppola caused to emerge from the clarinet were kaleidoscopic which worked in perfect companionship with the piano. The yearning for the remembered nostalgia for happier days was intense as Brahms approached death. A passionate forte section required a high degree of virtuosity in the clarinet which Coppola accomplished without limitation. His wide range of dynamics moderated the emotions to a high degree of eloquence

The short Andantino

was as if the composer took a pausing breath in an Intermezzo.

The final Con moto movement

possessed a lively forward movement. The piano and clarinet were here in a perfect symbiotic relationship. They moved through the glorious variations in a manner

both alluring and at times even humorous. I followed Hungarian folk elements

and perhaps Yiddish motifs too. One deeply melancholic variation prefigured

death. Overall a brilliant and inspiring performance which one is unlikely to

hear often in life. A treasure.

28.08.22

Sunday

20:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Symphonic Concert

Performers:

Piotr Alexewicz piano

Alexander

Gadjiev piano

Andrzej Boreyko conductor

|

| Andrzej Boreko and Alexander Gadjiev |

Program:

Nocturne in A flat major Op. 32 No. 2

This orchestral arrangement of Chopin’s Nocturne in A major Op.32/2 commissioned from Stravinsky by Diaghilev for Les Sylphides by the Ballets Russes at the spectacular premiere saison russe of ballet at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris in 1909. I fond it interesting rather than nocturnally reflective, elegaic and romantic. The passionate agitation towards the conclusion was enhanced by the orchestral dynamic. Alexewicz is a fine young Polish pianist of enormous promise.

|

| Piotr Alexewicz |

Fantasy in A major on Polish Airs Op. 13

|

| Andrzej Panufnik (1914-1991) |

I had never heard this concerto by the great Polish composer. I quote him and his posthumous website, by far the best authority on its true nature.

Andrzej Panufnik’s Piano Concerto has had a long and interesting history. It has been accepted that the original version of the work is a two-movement work, because for years the concerto indeed functioned as a composition comprising two parts – the contemplative Molto tranquillo and the virtuoso Molto agitato. The Piano Concerto received its current, three-part form only in the mid-1980s, when the composer added the introductory Entrata.

Entrata – despite the fact that it slightly

resembles the musical material from the earlier first movement of the concerto

– is markedly shorter (lasting only about 4 minutes) and is more of an introduction

and preparation for the main, slow movement of the work. For the

contemplative middle movement is undoubtedly the main part of Panufnik’s Piano

Concerto – its most important element, marked by piano sounds of

extraordinary beauty, full of poetry and gentleness, subtly and tastefully

embellished by the sounds of the orchestra.

It was in the

three-part version from the early 1980s (the composer modified the Entrata again

in 1985) that Andrzej Panufnik’s Piano Concerto functions

today.

In May 1983 the Piano

Concerto was recorded for the BBC Radio by John Ogdon and the BBC

Symphony Orchestra under the composer’s baton; the first studio recording was

not made until 1991, barely a few months before the death of Panufnik, who

conducted the London Symphony Orchestra with Ewa Pobłocka as the soloist.

My purpose

was to compose a virtuoso work for the pianist which would give him the chance

to demonstrate his capacity for poetic expression as well as his technical

skill and bravura. I wanted also to exploit and explore the sonoric range of

the piano, from sustained, singing notes to very dry, percussive sounds. In

addition, I wanted to make the orchestra's participation one of real significance,

with a powerful role to play. The Concerto has two movements: Molto

tranquillo (very slow) and Molto agitato (very fast) – each of

which imposes upon the performer and listener a definite climate and character.

The first

movement is an extremely quiet, contemplative dialogue between soloist and

orchestra (while within the orchestra there is a further dialogue between the

wind instruments and the strings). I made constant use of the palindromic form

creating a kind of lyrical geometry in order to emphasise meditative and

reflective feelings. As regards the musical material, I imposed upon myself a

strict discipline, this movement being based on the intervals of one minor and

one major second as a 'basic sound' within the framework of the mirror construction.

The second

movement follows attacca, with a violent outburst from the orchestra. This

movement again is based on only two intervals: this time a major third and

minor third. By the persistent repetition of these intervals, I wanted to

create an urgent sense of agitation, even turbulence. However, the middle

section of this movement is in contrast quite lyrical in character and based on

the material of the first movement (minor and major seconds), in order to

achieve some unity and firm binding together of these two deeply contrasted

blocks: Molto tranquillo and Molto agitato.

I found the orchestral timbre absolutely fantastic in its variety. Gadjieff expressed the Larghetto with ultra subtle pianissimo. I entered an extraordinary dream world of great strangeness that was extremely introspective containing what one might term 'minimalist emotion'. I felt this pianist to be outstanding in such a contemporary work, when at times during the Chopin competition I was plagued by doubts. His view was reflective and religious in tone and contemplative meditation on the spiritual nature of life. The Presto agitato resembled a dynamic explosion. Boreyko the conductor was deeply and magnificently engaged with the orchestra. He conducted with excellent exactitude, the percussion extremes led towards almost nineteenth century harmonic resolutions. Gadjieff was simply overwhelming in the massive virtuosic cadenza (if I may call it that).

Pressing personal reasons unfortunately prevented me from returning for the Manuel de Falla after the intermission.

Manuel de Falla

Fuego fatuo

|

| Lady Camilla Panufnik and Alexander Gadjiev |

28.08.22

Sunday

17:00

Royal Castle

Concert Ballroom

Recital of

Songs

Performers:

Olga Pasiecznik soprano

Ewa Pobłocka period

piano (Erard 1849)

Program

The most beautiful Moniuszko Songs (2)

An extraordinarily graceful and moving recital of much refinement. I will give the songs their English translations as they are evocative of the nature of love and poetic in expressiveness. Both artists performed perfectly together in symbiosis, the subtle, discreet accompaniment of Pobłocka to the glorious, emotionally rich voice of Pasicznik. A truly uplifting concert of the most eloquent beauty.

To the bud - such an

alluring sentiment

The girl and the bird -

poetic wisdom cradled in lovely

simplicity as a girl sings to a bird of her l love

If someone could love me truly - again a delicate and simple sentiment couched in a delicate melody

Kittie - a apparently carefree, tuneful even joyful song which conceals a girl married against her

will

The goldfish - a melancholic

song which contains Moniuszko's best loved lyrics

Pasiecznik then Turned to the Ukrainian tragedy which she supports

intensely and gave us a Ukrainian

folk song unknown to me but emotionally devastating

Podolian elegy (Attachment) was an attractive song with rather melancholic reflections but

tripmphant optimism at the conclusion. It declares love for the motherland to

words by Tymon Zaborowski from his Podolian elegies under Turkish rule (1830).

Matchmaking - as one

might expect a jolly song to a mazurka rhythm

The

spinstress - a perpetuum mobile

in the piano part which swirls endlessly like a spinning wheel - superlative keyboard

writing and playing by Pobłocka

Naja's

Song - a girl talks to a bird

about her beloved. the piano art is complex and rich in harmonies

Menacing

girl - the rather threatening

aspects of this creature are slightly smoothed away by the krakowiak rhythm

Dumka

(Elegy - Come my darling) - is

a gloomy song of unrequited love, a girl longs for a young man who loves another.

Words by the Polish poet Jan Czeczot

A

singer abroad and Remberance

- The first is a charming, melodic song and thje second contains funereal

overtones, both to words by the Polish poet Józef Zaleski who was a participant

in the 1840 November Uprising. The latter was formerly an unknown song

published in modern times

The Cossack - again to words by Jan Czeczot, it was popular from its first performance. Based on a traditional song.

§

27.08.22

Saturday

20:00

Warsaw Philharmonic

Concert Hall

Chamber concert

Performers:

Yulianna Avdeeva piano

Vadym Kholodenko piano

Corina Belcea violin

Axel Schacher violin

Krzysztof Chorzelski viola

Antoine Lederlin cello

Program:

Piano Quintet in F minor

|

Augusta Holmès (1847-1903) in 1880

This was a period in French

musical history that returned to what might be termed 'absolute music'. Franck

was at the peak of his creativity and much influenced by Wagner. He began to

break new tonal ground and was once more attracted to chamber music

composition. The result was this remarkable, deeply sensual Quintet. Frank was

much romantically and physically attracted to his pupil Augusta Holmès

(1847-1903). Saint-Saëns, to whom the Quintet was dedicated by Franck, was

lamentably suffering from a condition of unrequited love for the same lady. The

unconcealed sensual passion expressed in this quintet upset him greatly during

the first performance on the 17th January 1880 where he played the piano part.

He allegedly stormed off the stage after the performance in a blue funk.

Kholodenko opened the Molto moderato quasi

lento in a highly passionate and magnificent

manner with the quartet. We encountered great psychological agitation of

an existentialist kind. The work emerged as almost symphonic in impact. The

theme of this movement is deeply expressive of sensual yearning and desire,

perfectly understood by all these remarkable performers.

The Lento con molto sentimento

again sang in soulful and

heartbreaking yearning for love. The theme was affectingly poignant with much

ardent feeling, yet with haunting fears and premonitions of betrayal. Many

unresolved fears lay here ....

The Allegro non troppo ma con

fuoco apportioned marvellous and eloquent string writing for each member of

the quartet. Corina Belvcea was sublime, ardent and impassioned in this

movement. Kholodenko was equally possessed by the musical spirit in the

repeated phrases - in many ways a call of despair in a potentially hopeless

cause. I found it almost fantastically symphonic and building tremendous drama

of erotic anticipation in the unresolved harmonies. As Stendhal once observed,

the power and intensity of love lies in the anticipation not in the fulfillment

of desire. In the heart can lurk a painful degree of anticlimactic satisfaction.

Piano Quintet in F minor Op. 18 (1944)

Weinberg was born in Warsaw into

a highly musical Jewish family at the close of the Great War. His

training at the highest level as a pianist was rudely interrupted by the Second

World War. They fled to the USSR but his parents died in a concentration camp

and he alone survived. It marked his psyche deeply which can be heard in his

magnificently tortured and troubled quintet. He considered composition a 'duty'

to those who had perished. One can hear the influence of Russian, Polish and

Jewish cultures in his music. Autobiographical memories of World War II and the

loss of the innocence of childhood suffuse his compositions.

Moderato con moto A rather symphonic texture that was not in the lest seductive, rather arrestingly realistic. Lyricism alternates with militarism. The Allegretto opens with a violin and cello duo leading to monumentally florid piano solo with fantastic driving forward rhythms, irresistible. Avdeeva was musically taken over and charismatically convincing in idiom, the intense quartet in companionship with effective pizzicato interludes. The movement has a magically varied sound palette and many references to Jewish musical idioms. In this Presto - scherzo third movement, Avdeeva was simply phenomenal and overwhelming in pianistic commitment and virtuosity. The ensemble playing was spectacular in this movement, a type of flaming energy was set alight. Sudden explosions of piano sound filled the hall with gunpowder. Avdeeva betrayed incandescent passion in this movement.

The Largo was possessed of a remarkable massed ensemble sound in the opening. It contained within it all the spiritual and physical horrors of the holocaust. Cries from the earth as the hand of death reach out to us from the grave. The string pianissimo sections were quite transporting into another realm of soul experience. The violin lament is taken over by the powerful solo piano. Here the composition was intensely expressive in the overall abstract construction of the movement. One heard a 'piano clock' ticking which together with the cello obligato was unique, disturbing yet elevating. The pizzicato became deeply unsettling in view of the current murderous events in Ukraine. The ultimate and profound sadness of loss in the heart of the Jewish race evolved into a desperately moving elegy.

The final impassioned Allegro agitato movement featured sharp, repeated phrases on viola, second violin and cello embodying fractured, cruelly broken Jewish folk dancing. Avdeeva never dominated here despite the opportunity but merely added discreetly to the deeply unsettling atmosphere. I could not help reflecting on the nobility and monumentality of this ensemble in this great work. I heard the ringing of a dislocated and disinherited mind in this movement. The piano cries are the echoes of the condemned. One is aware as the work concludes of the rise of protecting life forces that in many ways work to redeem the fatalism. Yet life ultimately fades in the profoundly affecting dynamic fading away of the conclusion to this movement.

An awe-inspiring performance of a chamber masterpiece by masterly musicians who understand the nature of foreign oppression, war and summary execution to its core.

27.08.22

Saturday

17:00

Royal Castle Ballroom

Vocal recital

Performers:

Mariusz Godlewski baritone

Radosław Kurek period

piano (Erard 1849)

Program:

The most beautiful of Moniuszko Songs (1)

Coversation (1) The attention of Polish emigrants is drawn nostalgically to their homeland

On The Nida - Deeply moving song and music - the words are poetically transporting

Migrating Bird - pervaded by the most beautiful imaginable imagery

Mother You are No More! No compulsion to indicate the loss of mother love here

The Village Chief - Charming rather rustic songs. The often affecting poetry is simple but lifted onto another plane by the music.

Ditty (above the river's placid waters) - A charming and passionate song

Angel-child - Such a tragic story and poem lies here. A mother is working in the fields during the heat of the summer harvest and places her baby on a grassy bank whilst she works. The baby tragically dies of heat stroke but nature transforms her into an angel.

A Ball on the Ice - A strong and powerful song

The Alderman's Song - Such a jolly song!

Matty - a song of resignation to fate. A mazur intertwines with a krakowiak dance as the farmer beset by disasters on every side continues to dance oblivious .....highly popular song in a country where unexpected, sudden catastrophic destruction was common...

If you wish to pursue this almost forgotten song repertoire (outside of Poland) do buy this NIFC recording.

26.08.22

Friday

21:30

Warsaw Philharmonic

Concert Hall

Symphonic Concert

Performers:

Eric Hoeprich clarinet

Bruce (Xiaoyu) Liu period

piano

Tomasz Ritter period

piano

Marek Moś conductor

Orchestra of the

Eighteenth Century

Program

Karol Kurpiński (1785-1857)Concerto for clarinet and orchestra in B flat major (reconstructed by Michał Dobrzyński - first performance) (1821-23)

|

| Karol Kurpiński (1785-1857) by the German artist Alexander Molinari (1772-1831) |

Karol Kurpiński was the most renowned composer in Warsaw during the first half of the nineteenth century - opera and chamber music composer, impresario and conductor. He prepared the ground for Polish music of the Romantic period but is a largely forgotten figure

The opening Allegro of this clarinet concerto is a masterpiece of composition for the instrument comparable to the clarinet concertos of Weber or Mozart. In keeping with the 'Polish syndrome of incompleteness' (Marcin Król) the final two movements are lost but replacements were here reconstructed by Michał Dobrzyński

This evening

the work began with the Andante and finished with the Allegro. This

movement is both charming and melodious with interesting melodic changes.

The Rondo. Allegretto struck me as the very finest of Bath Spa

or Bad Kissingen infinitely charming but quite inconsequential music. The

clarinet blended seamlessly with the orchestral music. The Allegro first movement

undoubtedly composed by Kurpiński was a lively and tuneful statement.

The historic period clarinet was highly successful in this context.

The virtuoso playing was so civilized and elegant in the atmosphere

he created.

Tumultuous applause from both orchestra and audience for Hoeprich

Piano Concerto in E flat major K. 482 (1785-1786)

|

| The Love Letter (1770) - Jean Honoré Fragonard |

The composition of this concerto was completed during Mozart working on La Nozze de Figaro. he was at the height of his Viennese popularity. Michael Kelly, an Irish tenor who pioneered the roles of Basilio and Don Curzio in this opera left a lively description of Mozart’s performance 'His feeling, the rapidity of his fingers, the great execution and strength of his left hand particularly, and the apparent inspiration of his modulations, astounded me.'

Mozart performed

this concerto possibly three times or more during his brief life. The colourful

woodwind writing, rather appropriately for this particular concert, utilizes clarinets

in place of the oboes of an orchestra of this time.

The opening Allegro pursues

a drum-roll figure and the orchestra, which is rather festive and melodically

undemanding, passes through different keys with the soloist. Mozart seems to

have been returning to entertaining 'social' music to please his Viennese

audience. Ritter playing the exceptional McNulty Graf was

delightful with finely controlled dynamic contrast, balance and attention to

detail in his 'conversational' exchanges with the orchestra. He possesses a

fine sense of Mozart phrasing and rubato with an

excellent cadenza.

The melancholy Andante of song and variations on the other hand is deeply moving with its sense of despair and resignation. Mozart’s father Leopold wrote that it was much appreciated by the audience: 'the Andante had to be repeated (something rare).' The alternation of major and minor keys anticipated the coming Romantic movement and was popular.

The Finale is an Allegro in the form

of a Rondo which dispels the gloom. The sun emerges from behind the darker

clouds of threatening destiny. Ritter added some discreet, graceful and

tasteful ornaments with a fine rather elaborate cadenza. A wonderful theme lies

embedded here and the joining of full orchestra with soloist was so uplifting.

Ritter has a highly developed sense of one and touch on the earlier instrument.

On occasion I felt a lack of that eighteenth century affectation, social artfulness

and guile that takes us incontrovertibly into the period.

A copy of

the Viennese Conrad Graf’s instrument from c.1819, made in Paul

McNulty’s workshop in 2007 to a commission from the Fryderyk Chopin Institute.

This type of

piano was very popular in the early Romantic era. Chopin probably composed some

of his youthful pieces on a similar one. This instrument has the Viennese

action with the so-called single repetition. Unlike modern pianos, its hammers

are covered with leather. Most of the strings (single-, double- and

triple-strung) are made of iron wire, except the bass strings, made from brass.

The instrument does not have an iron frame. It has four pedals – moderator,

double moderator, sustaining and una corda – allowing for a wide range of both

dynamics and tone colours. The compass of the keyboard is 6½ octaves (C1–f4).

Symphony No. 98 in

B flat major Hob. I/98

The work opens with a pleasant Adagio which serves as a gentle introduction to the energetic Allegro. The conductor Marek Moś and the rejuvenated Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century made much of the complex internal polyphonic and contrapuntal detail.

The renowned musicologist and composer Donald Tovey suggested that the beautiful cantabile Adagio was Haydn’s requiem for his friend Mozart, who had died the previous December. It has a supremely civilized, elegant and graceful Viennese theme. Certainly the echoes of the ‘Jupiter’ Symphony’s Andante are clear in this exquisite movement, in full sonata form. In the recapitulation, Haydn seems to have modelled the hymn-like main theme on ‘God save the King’.

The Menuetto Presto charms one inexorably as rather a celebratory, festive movement. The Finale Presto is replete with eloquent, short phrases possessing inspiring energy, sparkling wit and humour. The many changes of instrumentation in the orchestral writing is extraordinarily effective.

A magnificent symphony with a fine, eminently suitable orchestra and idiomatic conducting. The concertmaster of the orchestra was particularly extravagant in gesture and musical involvement.

|

| Alexander Janiczek the flamboyant concertmaster of the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century |

Was it a celeste I heard that

decorated the conclusion - certainly Haydn wrote a solo piece for himself for

the harpsichord or fortepiano that would have galvanized the audience no end!

Variations in B flat major on a theme from Mozart’s ‘Don Giovanni’ (‘Là ci darem la mano’) Op. 2

Twice in the same evening and on a modern and period piano ! Also with the same outstanding artist who is rather a master of the style brillante, eminently suitable for this early work of Chopin. I have written about the genesis and character of this work in my criticism below. I found this piano sound spectrum in balanced tandem with the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century perfectly satisfying.

I thought the whole tonal landscape, texture and atmosphere perfectly in period and with the brilliant technique of Liu, both exciting and joyful at once. He seems to have a natural gift for accommodating to the Erard and extracting a variegated colour palette from it. The timpani was rather overwhelming in impact at times but is added a rather exciting, expressive and dramatic impression lifting the work into unexplored realms. The entire performance was impressive in an utterly different way to earlier in the evening.

Wild and tumultuous applause which

led to an encore of Rameau - Les Sauvages

Erard, Paris 1858

This instrument (serial no. 30315) was built in Paris in 1858. It is veneered in rosewood, inlaid with ormolu frames.

This

instrument (serial no. 30315) was built in Paris in 1858. It is veneered in

rosewood, inlaid with ormolu frames. It has a composite frame connected with

screws, consisting of an iron pinning table and six stress bars, a predecessor

of today’s full cast iron frame, with a bar brace in the treble. It is single-,

double- and triple-strung, with wound bass strings and una corda and damper

pedals. The keyboard compass covers seven octaves (A2–a4),

as in modern instruments. The piano is equipped with a typical Erard action, a

prototype of the double repetition English action generally used today. This

instrument was bought in 2010 and renovated in the workshop of Grzegorz

Machnacki.

26.08.22

Friday

18:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Piano recital

Performer

Bruce (Xiaoyu) Liu piano

First Prize at the 18th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw 2021

Program

Liu did not attempt to imitate the harpsichord by over articulation of Rameau on the piano, a 'fault' that even Grigory Sokolov is prone to despite the overwhelming impact he makes in this work. Liu gives a subtle and judicious touch of the pedal which softens the attack and takes the Rameau into an additional tonal realm.

Les tendres plaints

Charming playing for the reasons outlined above

Les Cyclopes

Excellent 'period feel' but could have

been slightly more detached for my taste

Menuets I and II

Refinement of touch and approach. A

French, even impressionistic, feel was given to the piece by Liu

Les sauvages

Lively and definitely pagan

La poule

True to title, Liu humorously and impressively

created a work tremendously reminiscent of a chicken

Gavotte et six doubles

He made charming, melodious and judicious use of

the pedal. He was not tempted, as are too many, to over-virtuosity. He perceptively

and musically revealed the embedded counterpoint and polyphony but overall I

was looking for slightly more emotional expression. As a harpsichordist I must admit to

preferring this work on the instrument for which it was written!

|

Variations in B flat major on a theme from Mozart’s ‘Don Giovanni’ (‘Là ci darem la mano’) Op. 2

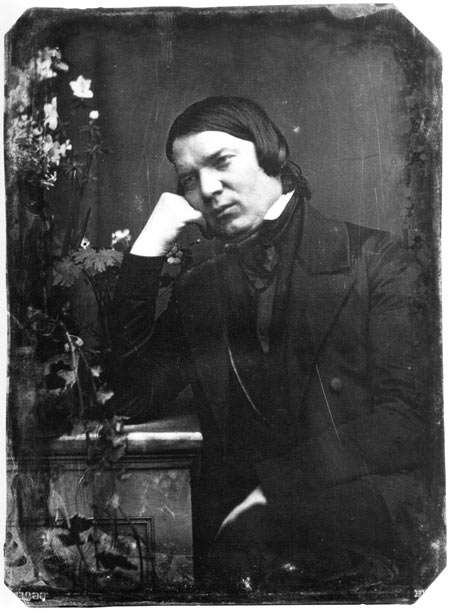

Chopin composed the ‘Là ci darem’ Variations in 1827. As a student of the Main School of Music, he had received from Elsner another compositional task: to write a set of variations for piano with orchestral accompaniment. As his theme, he chose the famous duet between Zerlina and Don Giovanni from the first act of Mozart’s opera Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni. In this opera overwhelming power and faultless seduction meet maidenly naivety and barely controlled fascination. (Tomaszewski)

|

'Là ci darem la mano' Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942)

(National Trust, Fenton House)

In his famous first review of Chopin's variations on Mozart’s 'Là ci darem la mano', Schumann gives us a striking description:

“Eusebius quietly opened the door the other day. You know the ironic smile on his pale face, with which he invites attention. I was sitting at the piano with Florestan. As you know, he is one of those rare musical personalities who seem to anticipate everything that is new, extraordinary, and meant for the future. But today he was in for a surprise. Eusebius showed us a piece of music and exclaimed: ‘Hats off, gentlemen, a genius! Eusebius laid a piece of music on the piano rack. […] Chopin – I have never heard the name – who can he be? […] every measure betrays his genius!’”

Chopin’s ‘Là ci darem’ variations are classical in form with an introduction, theme, five variations and finale. They are a marvellous example of the style brillante and clearly influenced by Hummel and Moscheles.

Liu gave us a pleasant sotto voce opening as correctly indicated and a deliberate tempo marked Largo that opens the work without the over-declamatory virtuoso energy many pianists adopt. Possibly it slightly lacked an undertone of beguiling seduction. It is well-known Chopin was obsessed with opera all his life, a fascination that began early. Liu applied phrasing that was uncannily as if the aria was being sung with vocal intonation and alluring and charming cantabile.

He applied winning dynamic variation in repeated phrases with a fine variety of tone and touch in developments that were light, elegant and stylish. Each variation had an individual character and the feeling of carefree and enjoyable improvisation. Liu never presented this work as simply a piano display piece although occasionally charm fell victim to irresistible and tempting virtuosity of youth. Liu brought a feeling of the late 18th century in his style and artfulness. Waterfalls of glittering notes cascaded around us as in the original descriptions of jeu perlé.

Clara Wieck loved this work and performed it often making it popular in Germany. Her notorious father, who had forbidden her marriage to Robert Schumann, wrote perceptively and rather ironically of this work: ‘In his Variations, Chopin brought out all the wildness and impertinence of the Don’s life and deeds, filled with danger and amorous adventures. And he did so in the most bold and brilliant way’.

Maurice Ravel

Miroirs

Noctuelles (Night Moths)

Ravel dedicated this work to the poet Léon-Paul Fargue.

“Les

Noctuelles des hangars partent, d’un vol gauche, Cravater d’autres poutres -

The night moths launch themselves clumsily from their barnes, to settle on

other perches”

Liu produced an extraordinarily fine and arresting glistening sound from the Steinway on this occasion (unlike the Fazioli he used for the same work in Duszniki Zdrój on August 5th 2022). He effortlessly created the image of flitting moths in my mind's eye. In this fiendishly difficult piece his impressionistic control and range of colour, nuance and articulated detail was excellent. Moths are fragile creatures and the light, silent fluttering became clear.

Liu moved from the rapid delicacy of fluttering wings to the expressive human emotions interwoven between them. In addition, dynamic indications in this piece move suddenly and quickly from one extreme to another. He indicated the mercurial unpredictability of the fluttering dusty wings of night moths on a still summer night. This effect was achieved in the inner ears of many visitors who were ravished by the superb sound of the Fazioli instrument

Oiseaux tristes (Sad

Birds)

In his autobiographical sketch Ravel said of this piece: “It evokes birds lost in the oppressiveness of a very dark forest during the hottest hours of summer”

Ricardo Viñes initially performed this piece on January 6, 1906 and it was also dedicated to him. The work may have been inspired by a story that Viñes told Ravel about meeting Debussy, where he heard the composer say that he wished to write a piece in a form so free that it would feel like an improvisation. His initial epiphany for this piece came during a walk in the forest of Fontainebleau. There are two planes: on the first the birds are singing and below this lies the threatening atmosphere of the dark forest.

Liu created a sound of delicate melancholy and impressionistic feeling. He accomplished eloquence and the delicate expressive resonance of repeated figuration of the opening fingering to perfection. One could see in sound imagination the rainbow of birdsong above the dark impenetrable green foliage hovering below. The feeling of a highly imaginative improvisation was always abundant.

Une

barque sur l’océan (A

Boat on the Ocean)

The depiction of water is the concern here. Ravel orchestrated the work but it is far more successful on the piano. Oliver Messiaen commented on this orchestration:

“There exists an orchestral kind of piano writing which is more orchestral than the orchestra itself and which, with a real orchestra it is impossible to realize”.

Liu created the image of a ship on the open ocean riding irresistible currents in his dynamic variation, colour and

use of the pedal. He gave us a feeling of the powerful swells of the ocean, the

breaking white caps in the wind as one sails and undulates over the surface in

arabesques. Some currents seemed deep and threatening. His control and use of

colour and nuance, sometimes harsh, sometimes calm and erotic was sensually

quite ravishing. He captured the surface of open ocean to perfection - one

could even smell and taste the salt air.

This familiar musical movement was

inspired of course by Spanish music. Guitar, castanet rhythms and repetitions.

It is high in incandescent, passionate southern energy peculiar to the

Iberian Peninsula. Rhythmically it was tremendously effective with a true

'biting touch'! The middle section involves a lyrical, improvised song known as

the cante jondo, or ‘deep song’. This Tzigane lamenting cante

jondo originated in the Spanish Andalusian flamenco vocal tradition

and Liu was imaginative in taking us into the interior of a smoke-filled tavern

of formidable, almost flamenco Spanish atmosphere. A magnificent performance of

driving rhythms and forward impetus as he wound up the tension to a conclusion

full of fireworks.

Here we have an impressionistic

sound painting depicting different bells sounding through a valley. Each bell

has its particular color and register (brought out expressively by Liu). Also

he emphasized the characteristic dynamic levels in which the ebb and flow of

sound indicated various distances from the source of the bells in their towers.

Calm, tender and soothing - Ravel marked the score calme and doux. The

piece opens and ends with the same material of the various sounding bells while

its middle section contains a long and generous chant.

Réminiscences de Don Juan, S 418

|

| Don Giovanni and Zerlina Duet |

The performance of this work in Warsaw so soon after Duszniki Zdrój was not radically different so I offer my rather similar review to that of 5 August 2022 without apology.

I have always considered the 'reminiscence' to be as defined by the Oxford Dictionary as 'A story told about a past event remembered by the narrator.' In this case the spectacular virtuosic display we heard from Liu was more like a recreation of the opera itself than a past event remembered through the filter of time. Then again when the Russian critic Vladimir Stasov, attended a Liszt recital of this work in St. Petersburg in 1839 he wrote:

'We had never in our lives heard anything like this; we had never been in the presence of such a brilliant, passionate, demonic temperament, at one moment rushing like a whirlwind, at another pouring forth cascades of tender beauty and grace. Liszt's playing was absolutely overwhelming...'