Piano Congress - Warsaw 2-4 September 2022

|

| The relaxing venue of the Piano Congress |

I have now attended this remarkable event. Here is a brief report on the presentations I attended. I will soon resume the completion of my music reviews for the International Duszniki Zdroj Festival 2022 and the Chopin and His Europe festival Warsaw 2022.

https://pianocongress.org/category/news/

The Piano Today

'From one genius to another'

(Udo Steingraeber)

This Piano

Congress was a particularly interesting Warsaw event to attend as it is the

opposite side of the coin to my normal preoccupation with the

music, performers, interpretations, festivals, competitions and the actual

sound of the instruments. It is held in a different capital city each year and this was the first time it had been held in Warsaw.

The

participants were modern designers of modern and historic copies of

instruments displayed with many examples of established brands

(Steinway, Yamaha, Steingraeber, Bechstein, Petrof, Ibach, McNulty ..... both

uprights and grands). Also present for consultation and discussion were

piano businessmen, manufacturers, piano technicians, tuners, practitioners

of the art of tuning, high-level maintenance specialists and a few

young pianists. Also displayed were many highly evolved modern accessories such as piano transport trolleys. Strict relative humidity control is vital in the storage and stability of historical and modern pianos which I discussed with Molly Lee, the Marketing Director of an American company, the Dampp-Chaser Corporation. They displayed a device attached to the instrument called Piano Life Saver which performs this dehumidification function www.pianolifesaver.com

All brands presented important, different and interesting perspectives and examples of the

still evolving technical and instrumental design of the piano. It is clear that the increasing interest in period piano performance is beginning to affect the design of modern instruments in a surprisingly retrograde fashion as the unique qualities of the sound and the quest for truth to the composer's original intentions is beginning to be recognized once again. A complementary

yet indispensable world to the performers' universe.

I feel it

incumbent on music conservatoires and universities to at least give music

students an introduction to the inner complex working of the piano

itself, this great machine, to give them a greater insight into the techniques

of manufacture and mechanisms that actually result in the sound produced with

their fingers, arms, body and mind. The final sound does not happen by

chance and of course is an utterly different mechanical process to a string or

wind instrument which have no moving or a relatively simple set of

moving parts.

A shining

example of this attitude to possessing a working knowledge of the mechanism of this complex

magic box is the great pianist Krystian Zimerman who can actually build a

piano, regulate, maintain, tune and adjust it himself to his own

demanding requirements. He prepared his piano with a Brahmsian tuning in a

superb recital I heard in Berlin of the magnificent 3rd sonata in F minor Op.5

of Brahms. This knowledge is considered an eccentricity - not so. It is a

highly intelligent decision and should be more widely disseminated as

a necessity among pianos students. I believe this is already being done in

Poland at, for example, the renowned Krzysztof Penderecki Academy of

Music in Kraków.

This point was forcibly made during the talk I attended entitled:

Historical features of piano touch and sound should be included in modern piano construction – a plea for a reinvention of lost registers and sounds

Udo Steingraeber

He began by indicating how composers determined the energetic development of the piano during the 18th and 19th centuries.The dominance of the composer-pianist was highlighted. As the century closed and the 20th century opened, the piano became increasingly less important as a vehicle of expression. Composers turned to alternative tonal and atonal methods of composition which no longer required them to express their creative thoughts through the piano. Its development slowed to a trickle and began to stagnate. Now technology has entered the picture which has led to new developments.

Six pedals were available to pianists from Beethoven to Chopin – some (e.g. Beethoven) switched between different pianos because of different key depths . . . the goal of piano design should be to allow performers the maximum expressive possibilities in artistic interpretation.

He also mentioned some matters of interest to Poland. Fryderyk Chopin briefly visited Bayreuth in 1836 but an account of his activities there are unrecorded. In the Warsaw opera house there is stored one of the rare Steingraeber bells of the Holy Grail used for the production of Wagner’s Parsifal.

Some questions are posed. Do we piano builders in the 21st century really contribute enough to the maximum richness of variations? Or were our colleagues of the 19th century superior to us?

|

| Udo Steingraeber |

This fascinating talk was given by Udo Steingraeber, the 6th generation to head up Bayreuth’s piano manufacturer, Steingraeber & Söhne, where he also learned piano building. He studied law and theatre at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. Eduard Steingraeber, the founder of the company in Bayreuth, was his great-great-great uncle. Between 1980 and 2009, Udo Steingraeber and the Steingraeber design team developed three new concert grands, various chamber and salon grands, and concert pianos. Most were for his own firm, but some, such as the new Pleyel grand piano 280, were commissions from colleagues in the piano industry. Since 1988, Steingraeber & Sons’ innovations have continuously won prizes at every Paris piano test of the top-flight instruments. Some were awarded independently, some jointly with the five, top-quality colleagues that comprise the small group of the world’s A-1 best manufacturers, as they are designated in the US rankings.

Steingraeber & Söhne abides by his credo, 'The technical development of the piano is never completed as the musical development goes on as well'. The Steingraeber construction design team has created a whole series of innovative products that complement Steingraeber & Söhne classic pianos, which are built along extremely traditional lines. These innovations include e.g. carbon fibre soundboards, SFM actions for upright pianos, Sordino and Mozart rail for grand pianos, magnet-controlled pedals for wheelchair users and recently the Transducer piano.

The company were generously giving away various free gifts which included a small white Meissen medallion with a profile of Liszt and on the reverse their magnificent 19th century period factory building.

Also a CD (OEHMS Classics OC 453) featuring a modern Steingraeber Concert Grand Piano with the pianist Jura Margulis's invention or rather attachment of an expressive sordino pedal. In the 18th and 19th century depressing this pedal introduced a thin layer of leather or felt between the hammers and the string. This gave with pp and ppp '...a sound of distant beauty and intimacy, a sound of infinite tenderness and penumbrian light..' which cannot be achieved on the open string of a modern instrument. The CD presents some interesting transcriptions of Bach, Mozart, Puccini, Liszt, Schumann and Mussorgsky made by Margulis and a Piano Duo with Martha Argerich of the Mussorgsky Night on Bald Mountain. She enthusiastically endorsed this sordino addition calling it 'an inspired invention'.

They also generously included a CD recording of pieces played by renowned artists on many of the different sizes of grand piano models they offer.

I felt that the Steingraeber presentation was by far the most impressive display of modern instruments at the Piano Congress. There was even an upright piano with matt case, utilitarian finish and drilled with small holes, specifically designed for operatic rehearsals.

Far more information is available on their website which I advise you to to examine. These pianos are endorsed by many famous players including Arcadi Volodos, Paul Badura-Skoda, Cyprien Katsaris, Martha Argerich, Alfred Brendel, Leif Ove Andsnes, Marc Andre Hamelin, Kit Armstrong....

The Piano Yesterday

The

specificity of Camille Pleyel's pianos in F. Chopin’s period in Paris

Amerigo Olivier Fadini

Description:

– Introduction: Intimate relationship between the Pleyel pianos and Chopin

– Main content

1. The characteristics of the sound with references to historical sources

– Evidence from Chopin’s letters

– Commentaries by musicians and critics of the time

2. What factors contribute to the creation of such sound

– An evolution from the pianino (the first ones were produced at the same year

of Ignace Pleyel’s death) to grand piano

– Research on the Pleyel pianos that have kept the original material and

structure (e.g. 3 pianos of 1844: Rossini’s Pleyel in Bologna, Italy etc.)

– the mechanics

– the felt (the material used, the density and size) with demonstration

3. Historical context of music making at the time

– performances mainly took place in salons for a relatively small audience

(still very much influenced by the tradition from the 18th century)

– the design of the Pleyel pianos was ideal for such settings

–Chopin always preferred to play in salons for a small circle of friends (eg.

Eugene Delacroix etc.)

Amerigo Olivier Fadini: Harpsichord maker, and pianoforte restorer who specializes in instruments from the romantic period. He has conducted a wide range of researches, particularly on the pianos manufactured by Pleyel & Cie under the inspired direction of Camille Pleyel.

In 2007, Amerigo made a first study of F Chopin’s Pleyel pianino in Majorca. This led him to advance his research with a focus on hammer felt made by Pleyel.

In 2010, he restored an important Neapolitan harpsichord from the 18th century, as well as numerous Pleyel pianofortes, including the one that had belonged to Caroline Bonaparte. Instruments restored by him have been used for making several recordings and videos: Un hiver à Majorque: Préludes, Nocturnes, Mazurkas by Chopin performed by Aya Okuyama on a Pleyel Pianino from 1838; Chopin: Œuvres pour violoncelle & piano performed by Ophélie Gaillard and Edna Stern using a Pleyel piano from 1843; other recordings were made by renowned artists including Tobias Koch, François Verry, Davide Perniceni, Alain Planès, Ludovic Van Hellemont and most recently, Yves Henry (Chopin à Nohant – La Chambre Enchantée ed. Soupir 2022 performed on a Pleyel piano from 1839).

In 2015, he was invited to Kraków by the Jagiellonian University to study two important Pleyel pianos: one owned by Jane Stirling, the other owned by Countess K. Potocka. He restored the Pleyel pianino No.10112 which was once belonged to Countess Obreskoff, a close friend of Chopin. The restored pianino was first used in a public recital performed by Alexei Lubimov on 10th August 2018 in Warsaw organized by the Chopin Institute. My review of this recording is here:

http://www.michael-moran.com/2020/10/the-pleyel-pianino-of-chopin-in.html

The recital was to present the 1st International Chopin Competition on Period Instruments, which was held in September that year.

My coverage of this competition is here:

http://www.michael-moran.com/2018/09/final-report-and-highlights-of-1st.html

In 2019, he also restored a Pleyel piano from 1851 for the Frédéric Chopin and George Sand Museum in Valldemossa, Spain. His research into the precious Pleyel Pianino No. 6668, which Chopin used in the winter of 1838/39 to finish composing his Preludes, was published in Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger’s book Autour des 24 Préludes de Frédéric Chopin.

Currently, he is restoring a Pleyel piano from 1844 for the Nohant Festival Chopin in France.

His talk emphasized the nature of the sound that was produced by the Pleyel pianos and pianinos of Chopin's day - mellow, round and intimate for the Salon. Chopin in his teaching concentrated on the production of a beautiful tone to the point of obsession. Something I strongly feel young pianists should take to heart today.

Berlioz remarked of the Pleyel pianino sound as having a 'marked melancholy character' with a 'sweet and argentine (silvery) sound - pure, mellow and singing. Antoine François Marmontel (1816–1898), a French pianist, composer, teacher and musicographer, spoke of the 'soft, veiled sonority' that created, a rather interestingly expressed, 'transparent vapour' - a sound like fine lace.

The figure of importance who emerges in the design of felt for piano hammers is Jean-Henri Pape (1789-1875) who took out a patent on green felt (anti-insect) in May 1826. Things then became rather technical in the examination and evolution of green, grey and white felt hammer coverings and their density which affected the sound quality which was rather beyond my modest 'little grey cells' to be honest!

This was followed by a brief mention of strings, metal and the Pleyel 'false soundboard' which is controversially suspended above the main soundboard and reputed to create an audible 'diffusion' of the sound.

The process of building the Buchholtz piano

Paul McNulty

|

| Paul McNulty instruments at the Piano Congress Warsaw 2022 https://www.fortepiano.eu/ There were remarkable performances by Viviana Sofronitsky of Beethoven's 'Moonlight' Sonata on the Walter copy and Brahms Intermezzi on the Streicher copy. She is the Canadian daughter of Vladimir Sofronitsky (1901-1961) the Soviet-Russian classical pianist of genius, best known as an interpreter of Alexander Scriabin and Fryderyk Chopin. All budding pianists should hear and play on these fine instruments. |

Chopin's

Piano

Cyprian Kamil Norwid

(Translated from Polish

by Jerome Rothenberg & Arie Galles)

And again, smokeblinded, I saw,

As it moved past the portal, the pillars,

A contraption that looked like a coffin

They were heaving out … crashing and crushing – your piano! (…)

That one! … that championed Poland, he from the heights

All-Perfections of history

People-bound, anthem ecstatic –

O Poland – of wheelwrights transformed;

That same one – crushed on the granite squares!

Is it you? – is it me? – then let’s strike up a Judgment Day song,

Urge them on: ‘Rejoice, o you child who will be! …

With groaning – stories gone deaf:

The Ideal – now brought low on the pavement’

First we had the screening of a fascinating and deeply moving film documenting the discovery in the Ukraine of the only surviving Buchhotz piano, the building of the copy followed by a short talk by the builder Paul McNulty with an opportunity for questions.

A modicum of instrumental history

On 19 September 1863 ‘the ideal was brought low on the pavement’. Chopin had been dead for 14 years, Buchholtz for 26. Had they lived, that symbolic moment would have been painful for both of them. On that September Saturday in 1863 in retaliation for an assassination attempt, (a failed one at that), the Tsarist governor Count Fyodor Berg and Tsarist soldiers plundered and looted the Zamoyski Palace at 67 Nowy Świat Street. The apartment number 69, belonging to the Barciński family, also fell victim to their barbarism.

Half a century earlier, around 1815, a certified organ-maker Fryderyk Buchholtz opened a piano-making workshop in Warsaw. Its first seat was at 1352 Mazowiecka Street. The manufacturer soon became considered the best in Congress Poland, in a large part thanks to its excellent performance at local industrial fairs in 1823 and 1825. A friend with the owner, Fryderyk Chopin was a frequent visitor at the workshop, where he would often play his newest pieces to his friends. After 1825 the Chopins bought a Buchholtz grand piano, which took the pride of place in their new apartment in the Krasiński Palace in Krakowskie Przedmieście and was used by young Fryderyk to compose his first great pieces, including his famous Piano Concerto in F minor. On 2 November 1830 Chopin left Warsaw; three days later he left his homeland forever. After his parents’ death, the grand piano was inherited by Fryderyk’s sister Izabella Barcińska. As mentioned above, on 19 September 1863, plundering the Zamoyski Palace, Tsarist soldiers threw the Buchholtz piano ‘out the window’.

The instrument on which teenage Chopin composed his first great pieces, including both his piano concertos, shattered into fragments on the pavement. Only a few instruments of the Buchholtz label have survived to today – all in a state rendering their ‘resurrection’ impossible. Using available prototypes, the Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Warsaw, which is a guardian of Chopin’s legacy and holds a collection of several instruments of the period, commissioned a copy of the Buchholtz grand piano. It was constructed by Paul McNulty, one of the best makers of historical pianos in the world. The first performance of the Piano Concerto in F minor by the composer was on 17 March 1830 at the National Theatre in Krasińskich Square on the Buchholtz piano.

This instrument is a copy of a grand piano by Fryderyk Buchholtz of Warsaw from c.1825–1826, held in the Museum of Local History in Kremenets, Ukraine.

It was based on the Viennese model which was popular at that time (built by the leading Viennese maker Conrad Graf, among others, and also employed by Polish makers). It was characterized by a case with rounded corners, resting on three turned column legs. The copy made by Paul McNulty is pyramid rosewood veneered, straight double-, triple strung, with a Viennese action, hammer heads covered with several layers of leather, wedge dampers and a 6½-octave keyboard with the compass C1–f4. This keyboard is broader than the original Buchholtz keyboard (6 octaves, F1–f4), with several additional notes in the bass, making it possible to perform the works Chopin was writing in the late 1830s. This piano also has four pedals operating following stops: una corda, moderator, double moderator and damper.

Here is an interesting account of the renovation of Chopin’s last Pleyel - Piano Factory No.14810 - by the conservator Paul McNulty. Warsaw Chopin Museum, Poland 3-12 December 2021

http://www.michael-moran.com/2021/12/the-renovation-of-chopins-last-piano.html

Film screening 'The soul of a piano'

This was a deeply moving film and quintessentially Polish!

The Piano

Congress featured the documentary film 'The Soul of a Piano' directed by

Judyta Fibiger.

|

| Gustaw Arnold Fibiger (1912-1989) |

Does a piano have a soul? If so, what is it? Is it elusive – or maybe its creator is a piano constructor? One of them was Gustav Arnold Fibiger, born in Kalisz in 1912. His passion for creating instruments survived even when his family factory was taken away after the war.

Who was he? A Pole with German roots who fought to defend Warsaw, a great patriot, but also the only piano constructor in Poland who led to the development of the music industry in our country.

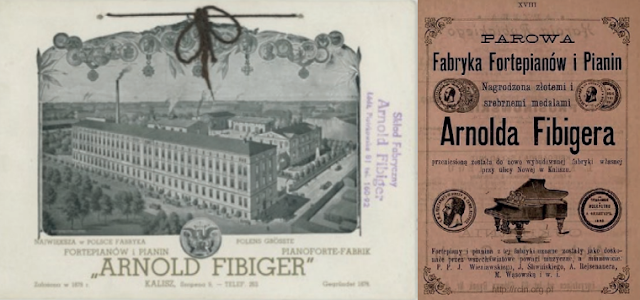

'The Soul of a Piano' is the story of the Arnold Fibiger Piano Factory, founded

in 1889 in Kalisz – the largest Polish piano factory. The documentary featured unique archival materials showing the nationalized factory, whose name

was illegally changed to 'Calisia' after the war by the communist authorities.

Kalisz is also particularly close to academy award winning composer Jan A.P. Kaczmarek, which is why he agreed to appear in the film.

Jan A.P. Kaczmarek: It was great that Gustaw Fibiger, even though the factory

was no longer his property, was able to enter this world, no longer run by

himself, and serve the idea of the perfect piano or grand piano. This was

extraordinary. Only people with great hearts, great spirits, can serve an idea

with such devotion. This idea was so deeply planted in him that he served it. I

am not surprised that a man of great passion will continue to do so, despite

the fact that circumstances have changed, because there is still hope and

persistence in him to help this idea, to make these pianos better and better,

to make them reflect this ideal world that can be conjured up from them

somewhere. For me, this is a manifestation of Gustaw Fibiger’s extraordinary

personality.

Kalisz and the old Fibiger factory is now the largest piano restoration centre in Poland.

|

| A restored Arnold Fibiger Concert Grand Piano |

Comments

Post a Comment