THE 12th INTERNATIONAL PADEREWSKI PIANO COMPETITION - BYDGOSZCZ, POLAND, November 6th – 20th, 2022

For those of you who have written to me concerning my absence as a reviewer and internet commentator in this competition, thank you. Disappointingly, I have simply not been engaged again for the competition. And yes, I was very fond of writing for this remarkable and uniquely inventive musical event over the past ten years. Justified policy development and modernization for the contemporary world takes precedence.

Tempus transit gelidum

The Canadian pianist, musicologist and writer Jarred Dunn has taken my place, a musician far more musically qualified and locally known in Bydgoszcz. He comments on performances and arranges high level musical contacts and interviews online locally with the jury, competitors, conductors and professors in the US and Canada. His work appears to be an engaging and constructive new connection and is functioning well. I am watching the competition with great interest online.

Good luck to all the courageous and talented participants and much support for the jury in a task I know to be supremely difficult and carrying great responsibility.

Results

2022 International Paderewski Piano Competition

First Prize Mateusz Krzyżowski (Poland)

Second Prize Pedro López Salas (Spain)

Third Prize Danylo Saienko (Ukraine)

Honourable Mention Piotr Pawlak (Poland)

Mateusz Krzyżowski (Poland) is definitely a most worthy winner!

K. Szymanowski Fantasy in C major, Op. 14

"The Fantasia in C major constitutes a distillation of the music of Szymanowski. It shows the intense influences of the music of the Romantic period–Chopin and Scriabin but also Liszt, Richard Strauss and Wagner during studies with Noskowski. This is a truly virtuoso piece that has not entered the repertoire of pianists. Krzyżowski with his particular affinity with the music of Szymanowski, acquitted himself magnificently in this relatively unknown work."

K. Szymanowski 4 Etudes, Op. 4

No. 1 in E-flat minor

No. 2 in G-flat major

No. 3 in B-flat minor

No. 4 in C major

You may find this link to the 2022 competition studio and reviews useful:

https://paderewskicompetition.pl/competition-page/25/competition-studio--reviews

However, in my reviews there was a great deal of additional information on Paderewski the man and his compositions. Some of it appears below. There were also insights into the former remarkable competitors and the context and cultural background of the pieces they performed. You may like to look at this sometime.

I consider these surveys as an important historical record of the competitions I participated in as a reviewer for over ten years.

The XI International Paderewski Piano Competition Bydgoszcz, Poland

Dang Thai Son - piano

Philharmonia Orchestra

Vladimir Ashkenazy - conductor

Ignacy Jan Paderewski [1860–1941]

1. Mélodie in G flat major, Op. 16 No. 2 * [1885]

2. Nocturne in B flat major, Op. 16 No. 4 * [1890]

3. Élégie in B minor, Op. 4 [1880]

4. Légende No. 1 in A flat major, Op. 16 No. 1 * [1886–1888]

Danses polonaises , Op. 5 [1881]

5. Krakowiak in E major No. 1

6. Mazurka in E minor No. 2

7. Krakowiak in B flat major No. 3

8. Minuet in G major, Op. 14 No. 1 ** [1886]

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 17 [1888]

9. Allegro

10. Romanze. Andante

11. Final. Allegro molto vivace

* Works from the cycle Miscellanea. Sériedemorceaux , Op . 16

** Work from the cycle Humoresques de concert , Op. 14

|

| Ignacy Jan Paderewski and his wife Helena Maria and son Alfred |

The music of Paderewski wears its learning lightly with poetry, charm, elegance and refinement of the highest order. His solo pieces are a neglected repertoire for young pianists and with luck might kindle poetry and charm in their playing.

My argument of neglect is validated by the only recording of his complete piano works I know of, made by the pianist Karol Radziwonowicz in Warsaw in 1991 in a co-production for the French Le Chant Du Monde label and the now dissolved Polish label Selene. To my knowledge it has never been reissued. LDC 278 1073/5 distributed by Harmonia Mundi. Used copies are available but at inflated prices.

Kevin Kenner has made a fine recording of the Paderewski A minor Piano Concerto Op. 17 and Polish fantasy for piano and orchestra op.19 with the Opera and Podlaska Philharmonic Orchestra in Białystock conducted by Marcin Nałęcz-Niesiołowski for the DUX label - DUX 0733

|

| Paderewski at 24 - a close likeness to his appearance during the writing of the concerto |

For me one of the finest interpretations of the Paderewski Piano Concerto in A minor Op.17 and Polish fantasy for piano and orchestra op.19 is by the Polish pianist Piotr Paleczny with the Sinfonia Varsovia conducted by Jerzy Maksymiuk. The BeArTon CD is available together with more information on Paderewski as well as the history and gestation of these two works using this link:

http://www.bearton.pl/en/the-best-of-paderewski-en/

It is a great pity that the Paderewski Piano Concerto has been so rarely prepared by any participant in this competition. A special prize is even offered for the finest interpretation. Such a lyrical and grand work full of piano pyrotechnics, noble harmonies, dance energy and infectious charm. Audiences would adore it!

For me still, the finest interpretation of the Paderewski Piano Concerto in A minor Op.17 is by the Polish pianist and Chairman of the Competition Jury Piotr Paleczny with the Sinfonia Varsovia conducted by Jerzy Maksymiuk.

The BeArTon CD is available together with more information on Paderewski as well as the history and gestation of these two works using this link:

http://www.bearton.pl/en/the-best-of-paderewski-en/

You can also hear the work on 'SoundCloud' together with the Polish Fantasy for Piano and Orchestra Op.19 here:

- I.J. Paderewski - Polish Fantasy For Piano And Orchestra Op. 19

https://soundcloud.com/piotr-paleczny-2/1-polish-fantasy-for-piano-and-orchestra-op-19

- I.J. Paderewski - Piano Concerto In A Minor Op. 17

- 1st mov. Allegro

- 2nd mov. Romanza. Andante

- 3rd mov. Allegro Molto Vivace

The fine English pianist Johnathan Plowright has also recorded the Concerto in A Minor Op. 17, the Polish Fantasia Op. 19, the Sonata Op.21 and the Variations and Fugues Op. 11 & Op. 23 for Hyperion.

Another outstandingly fine account of the Concerto and Fantasia is by Antoni Wit and the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra of Katowice with the superb virtuoso Janina Fialkowska as soloist on the Naxos label.

|

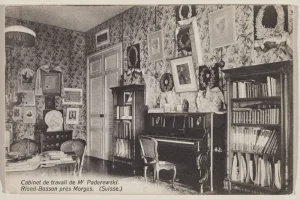

| Paderewski's Study at his villa near Morges, Switzerland |

|

| A Bosendorfer piano once owned by Paderewski in the superb Casimir Pulawski Museum, Warka, Poland |

|

| Paderewski collected silver spoons on his travels abroad as souvenirs. A small sample from the collection at the Casimir Puławski Museum at Warka some 50 kms from Warsaw. Poland |

|

| A sign of the power of the statesman - a 'Paderewski' Armoured Train during the Great War |

You may like to read this excellent and heartfelt article on Paderewski

ON THE 75TH ANNIVERSARY OF PADEREWSKI’S DEATH (29 June 1941)

‘Poland is immortal!’

Stanisław Dybowski

So said Ignacy Jan Paderewski on 23 January 1940 at the inaugural meeting of the National Council of the Republic of Poland in Paris, when the situation of the country occupied by two invaders was being pondered. He once said about himself: ‘I am neither lured by power nor attracted to the prestige of being the father of the nation and the more modest position of a useful son of his land would be more than sufficient to me’… and about himself as a pianist: ‘everybody told me – and I was beginning to believe it myself – that I would never be a pianist.'

And yet, his strong belief that Poland is immortal led him right up to the pinnacle of art and politics. He worked in both those areas in order to further his patriotic goals, to which he subordinated everything else!

‘Ignacy Jan Paderewski , said the Primate of Poland in 1986, ‘died in the united States. The funeral ceremonies lasted several days. First, a grand memorial service was held in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. Then, the body was carried to Washington, D.C., and, on 5 July 1941, was laid at Arlington cemetery with military honours. The coffin with the body was laid, but not interred. The funeral was not finished’. It was finished 51 years later, on 5 July 1992, in the presence of the Presidents of Poland and the united States, with the artist’s remains being placed in the crypt of St. John’s cathedral in Warsaw. Thus the will of the Great Pole was implemented, which was to be laid to rest in free Poland, for which he had fought as a politician and a statesman and the cause of which he had championed through his concerts, carrying the name of Frederic Chopin high on his banner.

In his excellent book on Paderewski Adam Zamoyski wrote the following beautiful words:

‘The name of Paderewski was on the lips of many generations. For people who knew nothing about music he was the embodiment of a pianist; for those who knew nothing about Poland he was the embodiment of a fiery Pole; finally, to those who did not have the faintest idea about his political career he looked like Moses – the leader of his people’.

Paderewski made a career – as was often written and said – on a cosmic scale. There has been no human being, before or after him, who enjoyed such a degree of popularity. Even Franz Liszt’s great career, limited to the European continent, could not equal the extent of influence exerted by Paderewski’s name. ‘It was sometimes enough, as poet Jan Lechoń wrote:

‘For Paderewski to appear on stage with his distant look, lion-like hair, a legendary white tie and a modest, almost humble demeanour, more reminiscent of some village bard than a great virtuoso, to make the public stand up and worship in him art itself, all that is unselfish, noble and generous in life and that everyone associated with Paderewski. Paderewski’s star rose in those sad times when Poland was absent from the map of Europe – he was a son of an unhappy country, with no proud embassies or wealthy patrons standing behind him and supporting his art.

However, Paderewski felt Chopin’s soul in his own soul; eager to listen to the voices in his heart, he found in them echoes of a thousand years of our beautiful and magnanimous history; […] listening to those mysterious voices, he felt that he was rich and strong. From the very first time he appeared on the art horizon he behaved like a king; having never asked anyone for anything he always wished to be generous to everyone and all his life was the fulfillment of that wish. […]No one represented true Poland in the eyes of the world better than Paderewski’.

He was formed as an artist at the Warsaw Institute of Music thanks to, among others, Professor Juliusz Janotha (1819–1883), an outstanding pianist and teacher. Professor Władysław Żeleński (1837–1921)gave the following correct assessment of the student’s personality:

‘A young eagle, of a noble breed, proud, courageous, ambitious, a bit aggressive and self-willed but, most of all, independent […]. He had an innate sense of what is right, rebelling against the existing state of affairs if he considered it wrong.’

The great Polish pianist and pedagogue Theodor Leschetizky (1830–1915), Paderewski’s last professor in Vienna, said the following about his pupil for the Tygodnik Ilustrowany weekly in 1899:

‘Paderewski… Paderewski…, repeated Leschetizky several times, as if caressing himself with that word. ‘My pride and honour … He will be a brilliant artist until the end of his days, because he has the character, because he did not and would not think of any goals other than his work … He studied under my guidance for four years, two of which were devoted by him solely to five-finger exercises, until he finally achieved what we call technique … Nowadays he may not be playing for months and will still not lose his skill; his fingers will play by themselves … This is how my system works – to make finger muscles independent from elbow and forearm muscles. It is then that you achieve total freedom … And the style? After the technique we worked on developing the style […], on reconciling the individuality of the virtuoso with the intentions of the composer. The artist's individuality is a small nucleus contained within a large number of sheaths. The teacher may change the latter, but the nucleus should remain untouched. […] Paderewski is a model that demonstrates exactly how a teacher should instruct his pupil to ensure that everything that his heart may feel and his head may think gets to his fingers through tiny nerve and muscle threads.’

Paderewski achieved everything with hard work, setting high standards for himself expectations and, then, pursuing them mercilessly; he was also always an adamant guardian of the values that he believed in. This manifested itself in him as a virtuoso pianist, a Pole – fighting for his land’s independence, a composer and a teacher. Those traits of his character were noticed by everyone and it was them that drew people to him.

As a Bonner Zeitung critic wrote:

‘Paderewski has become one with the piano just like Chopin did before him. For him the piano is everything – the eye, the ear, the heart and the mouth; the world sings to him in piano tones, he lives the piano and uses it to interact with the world’

while a Kurier Warszawski reporter wrote:

‘For a whole hour the public was flocking to Paderewski’s third concert. In the vestibule downstairs the crowd was filling the staircase and the antechamber on the first floor was so packed with people that any movement towards the grand hall was hardly possible. It did not matter to anyone that other people were treading on his or her feet; even the ladies were not offended if anyone stepped on their train or got caught in their laces. Never mind the train or the laces – we are going to hear Paderewski!’

Edward Risler (1873–1929), a famous pianist and professor at the Consevatoire de Paris, described him briefly as ‘A poet of the piano, a moving performer, a dazzling wizard with a noble heart, great in war and peace. Another piano master, Alfred Cortot (1877–1962), wrote the following in his letter to Paderewski:

‘Is it not to the marvellous charm of Chopin’s work that Poland owes its spiritual survival in human memory in the times of painful slavery? And is it not the inspired performer of his works that has been tasked with the mission of ensuring that his enslaved and martyred land becomes an independent state again? How wonderful and steeped in legend is the epic of a country that owes its liberation more to the lyre than to the sword! All of us who love and admire you are very happy to be able to honour you as a double hero – a hero of Art and of his Motherland!’

Paderewski was a virtuoso, but not in the colloquial, modern meaning of this word, i.e. a musician playing fast and loudly, but rather in the sense that it really expresses. The Latin ‘virtus’ means virtue, manhood, courage, strength and bravery, but also constancy. Those features were characteristic of him in all his activities. In this respect he was close to Chopin, with whom he shared similar views on art, the same love for music and the piano and the same strong uncompromising love for his Motherland!

Paderewski understood – better most people in the past and nowadays – these well-known truths when he said that ‘no country may be happy unless it is free and no country may be free unless it is strong’ and that ‘the cause of the nation is not an undertaking that one should abandon if it yields losses instead of profits. It is a continuous and regular effort, unwavering perseverance and uninterrupted devotion from generation to generation. It can never stop and no penny should ever be spared on it.

In his portrait dedicated to Paderewski the great French composer Charles Gounod wrote only three, but very significant, words: ‘To my dear, great and noble Paderewski’.

On the 75th anniversary of the death of the Great Pole his compatriots will honour him with concerts and the 10th Ignacy Jan Paderewski International Piano Competition to be held on 6–20 November in Bydgoszcz.

Copies of this discerning biography of Paderewski by the masterful author Adam Zamoyski are available on this link

Comments

Post a Comment