Recital by Andrzej Wierciński at St. Mary's Church, Perivale, Greater London on 1st December 2022

|

| Andrzej Wierciński |

As the years pass it is always a

great pleasure to witness the development of an artist. There are many

fine, young Polish pianists but few that flower in the convincing musical

manner of a summer bloom as Andrzej Wierciński. He gave an

outstanding recital in St. Mary's Church, in west London.

This intimate church, now one of the most important concert venues in London, is set in the picturesque rural

surroundings of Perivale, a small town in the Borough of Ealing. It is reputed to have

one of the fest acoustics in the capital.

The refined discrimination of this

pianist was clear from the outset when he chose to open his recital with one of

the seductive, cantabile sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti

(1685-1757). This sonata K 466 was particularly suitable for the

modern piano. It is highly likely Scarlatti conceived it for one of

the five recently invented Cristofori instruments (gravicembalo col piano e

forte) situated at the Spanish court, the Escorial, of his employer

Maria Barbara Braganza of Portugal, later Queen of Spain (1711-1758).

Many of his sonatas call for a feeling on

the harpsichord of strummed or plucked guitar with more than a hint of Spanish

garlic and strong sunlight but the vocal 'singing' sonatas are more

purely realized with appropriate bel canto on the piano.

Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1731) is generally considered the original

inventor of the piano. Many mechanical refinements and developments

followed the original cylindrical papier mache hammers until

we arrive at the developed instrument of today.

Wierciński has an expressive, seductive, singing cantabile tone and refined touch of delicate intensity with which he extracted a transparent, yearning polyphony. Such a piece was clearly intended for a Cristofori piano and was rendered with aesthetic distinction of a high order this afternoon.

|

| The 1720 Cristofori Piano The oldest surviving piano in the world |

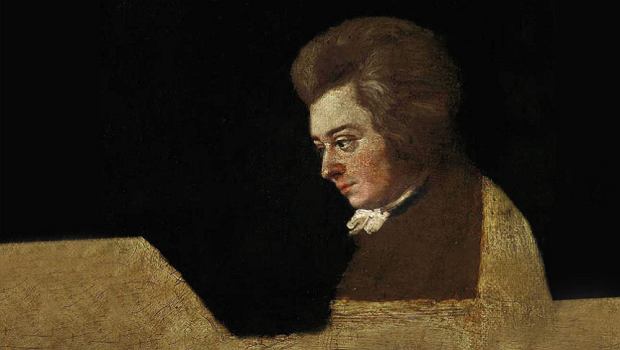

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Sonata in F major K 332

This sonata was composed in Paris in the summer

of 1778. It must be known to every child who has taken up the study of the

piano seriously!

The Allegro theme is

simplicity itself and Wierciński approached its growth with expressive,

lyrical phrasing that possessed that indispensable Mozartian central mood

of élan and panache - an interpretation both energetic and stylish. The movement had an

inevitability about its development. The Adagio could

have been more ardent and 'romantic' for my rather

over-expectant sentiments, but his phrasing was movingly eloquent,

sensitive and refined. The Allegro final movement was

marvellously stylish with glittering articulation and a high degree of

accuracy. Again he produced an arresting, ringing, alluring, rather silvery

tone from the smaller Yamaha at St. Mary's (a remarkable instrument in itself). His

pedaling ('a study for life' once observed Chopin) was highly

artistic and rendered the internal structure 'as clear as crystal'.

This was an excellent performance of

a Mozart sonata which struck an attractive classical balance with

much bon goût and graceful poise.

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Kreisleriana Op.16

Phantasien für das Pianoforte

Sehr innig und nicht zu rasch

Sehr aufgeregt

Sehr langsam

Sehr lebhaft

Sehr langsam

Sehr rasch

Schnell und spielend

This is without doubt one of my favourite works of romantic piano literature.

I make no apology for the following, perhaps overly long, detailed explanation of the metaphysics and referential literary inspiration for this extraordinary hyper-realistic work of musical art. Context is vital.

|

| E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776-1822) Staatliche Museen Berlin |

'Mad as a refuge from unbelief'

Extracted from a passage written by William Blake in 1816 onto the flyleaf of a book by William Cowper

Madness or insanity was a notion that throughout the composer's time on earth simultaneously attracted and repelled Schumann. At the end of his life he was cruelly to fall victim to it. Yet madness for the Romantic artist was a source of creative energy, 'an unpredictable source of inspiration' to quote Charles Rosen (The Romantic Generation pp.646-658).

Kriesleriana was presented publicly as eight sketches of the fictional character Kapellmeister Kreisler, a rather crazy conductor-composer who was a literary figure created by the marvellous German Romantic writer E.T.A. Hoffman (1776-1822) who possessed 'an overwhelming interest in music'.

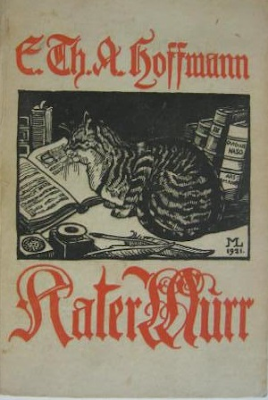

The piece is actually based on the Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier and also the double narrative form of an inventive grotesque satirical literary novel Hoffmann wrote with the remarkable, translated title: Growler the Cat’s Philosophy of Life Together with Fragments of the Biography of Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler from Random Sheets of the Printer’s Waste. It is one of the funniest novels in German Romantic literature. Hoffmann has had an immense influence on serious European writers, even world authors and universal fantastical literature, being a type of father figure to the modern concept of magic realism.

Schumann's work was partly a response to what he considered to be the demise of the sonata form post-Beethoven - '...it looks as if this form has run its course.' he wrote.

The fictional author of this double novel (two protagonists) Kater Murr (Growler the Cat) is actually a caricature of the German petit bourgeois class. 'O Appetite, thy name is Cat! With the herring head in my mouth I climbed to the roof, like pious Aeneas.' Certainly this is a bizarre work of literature!

Schumann even adopted a similarly 'zig-zagging' fragmented narrative style to the Hoffman novel in his Kreisleriana which tends to confuse some musicians. The words der Kreis in German means a 'circle' and the verb kreisen means 'to circle'. Schumann adopts a circular musical thematic narrative in this work.

In a theme rather appropriate in our times of gross financial inequalities, Growler advises the reader how to become a ‘fat cat’. This advice is interrupted by fragments of Kreisler’s impassioned biography. The bizarre explanation for this is that Growler tore up a copy of Kreisler’s biography to use as rough note paper for his own writing. When he sent the manuscript of his own book to the printers (with the Kreisler manuscript written in the reverse), the two got inexplicably mixed up when the book was published. Such curious literart devices remind one of Laurence Sterne in that great experimental novel Tristram Shandy.

|

| Lebensansichten

des Katers Murr (The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr) E.T.A Hoffmann 1820-22 (Illustration by Ernst Liebermann) |

Music and literature were inextricably connected

in Schumann's artistic aesthetic. He was particularly fond of Kreisleriana and

attracted to composing a work in ‘fragmented’ form in the structural manner of

this novel. The use of the device of interrelated ‘fragments’ (as the

nineteenth century termed what we might refer to as 'miniatures') was employed

by the Romantic Movement in poetry, prose and music. Schumann often likened the

listening to music to that of reading a novel. References to literature are

found in many of his compositions.

Kreisler is a type of Doppelgänger for Schumann. This was a favourite concept for the composer, who divided his own creative personality between the created characters of Florestan and Eusebius. With the unpredictable Kreisler as his alter ego, Schumann was able to indulge the dualities of his own personality. The music swings violently and suddenly between agitation (Florestan) and lyrical calm (Eusebius), between dread and elation. Or one might conjecture, between the composer Kreisler and the cat. The episodes in the piece describe Schumann's emotional passions, his divided personality and his creative art. His tortured soul alternates with lyrical love passages expressing the composer’s love for Clara Wieck. He used and transformed one of her musical themes in the work.

The work oscillates between two highly contrasting schemes of music. 1838 was a disturbed time for Schumann. His marriage to this 'inaccessible love', the piano virtuoso Clara Wieck, was a year ahead. At this time they were painfully petitioning the courts for permission to marry and ignore her father's cruel social class objections to the connection. They had known each other for ten years before their eventual marriage in 1840. During this turbulent period of frustration, Schumann’s compositions evolved in complexity. Their unbridled emotionalism and adventurous structure confused musicians, audience and critics alike. The work was written as predominantly oscillating between B-flat major (slow - lyric, expressive - legato flowing melody - small octaves) and G minor (rapid - non-lyric - dotted rhythms, rests, staccato notes - mechanistic repetitions - short motives - contra and great octaves).

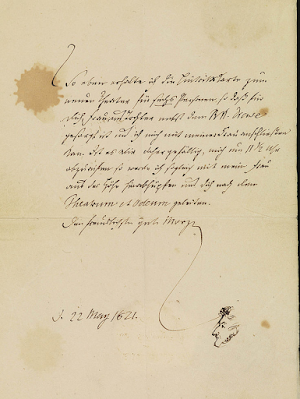

Schumann originally intended to dedicate the work to Clara, but wishing to avoid more calamitous situations with her father, who had violently forbidden their marriage, eventually dedicated it to his friend Fryderyk Chopin. He wrote the work in an astonishing four days in April 1838. The polyphonic nature of the piece may have reflected a deep understanding of Chopin's own style and certainly a love of Bach. The Polish composer merely commented on the cover design of the score left on his piano. Even Clara, on first acquaintance with the work, wrote: 'Sometimes your music actually frightens me, and I wonder: is it really true that the creator of such things is going to be my husband?' Even Franz Liszt was challenged finding the work 'too difficult for the public to digest.'

Schumann wrote to Clara in a letter:

'Play my Kreisleriana sometimes. You will find a wild, unbridled love in there in places, together with your life and mine, and many of your glances.' Also 'Oft these things (his works), I love the Kreisleriana the most.'

This great masterpiece of emotional and structural complexity expresses much of the quixotic mercurial temperament of Schumann's personality and the literary constructive elements of the story. Contrasting passages of great discontinuity run up against each other ironically but then finally converge.

|

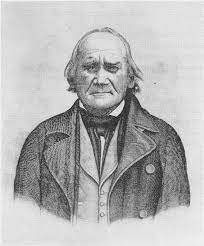

| Ludwig Böhner (1787-1860) |

In 1834 Schumann had met Hoffmann's role model

for the Kreisler figure, the composer Ludwig Böhner (1787-1860) in

Leipzig. 'You know that he was as famous as Beethoven in his time and

that the Hoffmann was sitting with his Kapellmeister Kreißler as the original…

The day before yesterday he fantasized with me for a few hours; the old

lightning bolts struck out here and there, but otherwise everything is dark and

dreary ... If I had the time, I would like to write Böhnerians for which he

gave me the material himself.'

The poetry of the form of the Kreisler section lies in its symbolic circularity (The French literary theorist and Schumann-lover Roland Barthes interestingly observed that Schumann composed music in discrete, intense 'images' rather than as an evolving musical 'language', like a succession of frames in a film). In the literary cycle, Kreisler becomes obsessed with Bach's Goldberg Variations and Schumann is catalyzed by this reference and his own adoration of the music of Bach to improvise complex variations on the Goldbergs in Kreisleriana. This, what one may call 'stretching' of Bach, and placing it transformed into the world of Romanticism, testifies to Kreisler's (and Schumann's) disturbed temperament at this time.

In Kater Murr: 'Unfortunately, the current biographer is forced to portray his hero, if the portrait should be correct, as an extravagant person who, especially when it comes to musical enthusiasm, often seems almost mad to the quiet observer.'

|

| A remarkable cat seated inscrutably in a window at Lądek-Zdrój, a beautiful Polish spa town in Lower Silesia |

The Swiss pianist and musical commentator Walther Rehberg (1900-1957) reinterpreted this psychologizing implementation of the Kreisler figure as projected onto Schumann's own psyche: 'So his own storms of the heart, but also his other, wide-ranging inner experiences that are not always compatible with the limits of the bearable, found expression in his Kreisleriana.' This refers to Schumann's self-image: He saw himself as a forerunner of a concept of art that broke the fetters of pleasant musical enjoyment and penetrated the 'romantic realm of spirits', threatened by the constant danger of brushing against madness.' (Karl Böhmer Villa Musica)

The composer was also experimenting with the timbre of piano sound. Without wishing to appear a 'crank', I feel it necessary to say that on a piano of Schumann's period (he loved Clara's Conrad Graf of 1838 from Vienna) the varied colours, timbre and textures of the different registers suited the contrapuntal nature of composition. This would have been rather more obvious on the older instrument than on the modern homogenized sound of the Steinway.

Such a temperamental and capricious work by Schumann (and the bizarre background story by E.T.A.Hoffmann) is difficult to present to modern listeners with great conviction and lucidity. Even Schumann once commented 'Only Germans can understand the title Kreisleriana.'

The reason for this apparent prejudice was that Hoffmann was scarcely read outside Germany at the time and even today scarcely read at all anywhere. So the extra literary dimension to understanding this work is often lost, particularly on young pianists who seem completely averse to reading the literary background and inspiration of the great works they are studying and practising so assiduously.

I will not analyse each movement of the work

save mentioning the beautiful poetry Wierciński expressed in the

arias and songs. I did feel this unpredictable, spontaneous, quick-silver,

moody aspect of the composer, flashes of lightning and the

spinning globules of mercury escaping its container. The

lyrical Eusebius qualities of the piece were beautifully

contrasted with the more energetic, fragmented driving, almost pathological

qualities of Florestan. I felt 'Eusebius' could have 'sung' romantically even

more, but that is me! He successfully established in the composition the Doppelgänger motif,

so embedded within the psyche of Schumann.

Wierciński expressed too the feeling of the hopeless love-yearning that at that time Robert had for Clara. As is well known, her father (who had actually given Schumann piano lessons), forbade their marriage in cruel terms and took hurtful steps to prevent it. Wierciński communicated these deeply personal feelings, emotions of yearning and suffering with the addition of fine, expressive and emotionally phrased legato.

His Kreisleriana progressed through lyrical interludes of sublime melody and periods of monumental, almost symphonic rhapsodic playing of quite disturbing violence and technical mastery. I found this musical journey under his guidance quite remarkable and brilliant. I even felt at times the frantic movements and articulation of a rather disturbed cat in his rhythms - staccato and demi-staccato - which is a rare experience indeed even with the greatest pianists! I once owned an unmanageable and neurotic Burmese Blue cat and have observed his antics!

Musically however, these passages could have breathed more air rather than been completely overcome and on occasion rushed, through his passionate utterance. The youthful exuberance he brought to the fugal writing was slightly exaggerated and unsettlingly fast and over-driven in urgent tempo, at least for me. A clearer internal polyphonic life could have been created for the listener who must be given time to decode the internal workings of these complex constructions. The almost unstoppable momentum of the final movement has direct parallels with Hoffmann's own hurtling narrative prose, until the irresistible rhythm finally fades into the dark nothingness of absolute space and silence.

All in all a fine and potent rendition of this challenging masterpiece.

Fryderyk Chopin

Andante spianato et Grande Polonaise Brillante in E flat major Op. 22

(1830-1834)

Certainly the Andante was spianato (smooth) with Wierciński's seductive tonal qualities on attractive display but the tempo could have been more overtly expressive and heart-felt for this romantic soul. However, his singing legato was notable for its warmth and the cantabile drew me into the work. At times, I felt his phrasing could have been a little more poignant and the fiorituras more cherished and meaningful as they are integral expressive aspects of the melodic line. Chopin often used to perform this work alone in a notably sympathetic manner.

|

| The danced polonaise |

The Grande Polonaise Brillante opened with a tremendous fanfare and confidence of spirit in this 'call to the floor'. The polonaise developed into a noble, dignified and aristocratic dance-based work. There was a striking clarity of energetic articulation leavened with great panache and élan.

The 19th century poet and critic Casimir Brodziński described the polonaise:

The polonaise breathes and paints the whole national character; the music of this dance, while admitting much art, combines something martial with a sweetness marked by the simplicity of manners of an agricultural people…….Our fathers danced it with a marvellous ability and a gravity full of nobleness; the dancer, making gliding steps with energy, but without skips, and caressing his moustache, varied his movements by the position of his sabre, of his cap, and of his tucked-up coat sleeves, distinctive signs of a free man and a warlike citizen.’

This work is a great challenge for pianists to play with perfect accuracy. One of the greatest performances I have heard was by another young outstanding Polish pianist, Wojciech Świtała, for Katowice Radio many years ago.I found the Wierciński account possessed all the stylish spirit of this singular national dance. His style brillante was almost electrical in its internal energy. In the day of say Johann Nepomuk Hummel, this style was characterized by lightness, delicacy, charm, sonority, purity, precision and a rippling execution resembling pearls – le son perlé. This work could only have been composed in a state of happiness and youthful ‘sweet sorrows’ living in his native land. Wierciński communicated all these sound qualities and a little more in terms of forward-driving momentum and infectious almost syncopated rhythms. A triumphant conclusion of power and strength elicited cheering and applause from the highly enthusiastic audience.

An exceptional recital by a fine young Polish pianist who possesses aristocratic, charismatic musical qualities rarely encountered today.

Recital and Interview with Dr. Hugh Mather

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a0CNw3qvjXQ

Comments

Post a Comment