Fryderyk Chopin 213th Birthday Concerts 1st.March 2023 - Birthplace at Żelazowa Wola and the Warsaw Philharmonic - Szymon Nehring and Yulianna Avdeeva

On 1 March 2023, the 213rd anniversary of Fryderyk Chopin's birth, the National Chopin Institute invited us to two concerts:

|

| The birthplace of Fryderyk Chopin at Żelazowa Wola |

Nocturne in D flat major, Op. 27 No. 2

A rendition with fine and affecting phrasing and rubato (especially in the opening cantilena) of 'the romance variety' of Chopin nocturne. The polyphony, so important in Chopin's compositions, was transparent and moving. Tender, a dreamlike stroll on a summer night creating poetry together in love, gazing into the starry and moonlit sky, yet not sentimental.

In his Notes on Chopin, André Gide captured this kind of music in words with penetrating intuition: ‘[Chopin] seemed to be constantly seeking, inventing, discovering his thought little by little. This kind of charming hesitation, of surprise and delight, ceases to be possible if the work is presented to us, no longer in a state of successive formation, but as an already perfect, precise and objective whole.’

Scherzo in E major, Op. 54

This is a rarely presented unusual scherzo. The work is not dramatic in the demonic sense of the three previous scherzi, but lighter in emotional ambiance. The outer sections are a strange exercise in rather joke-filled fun with a darkly concealed centre of passionate grotesquerie dependent on the accentuation of rhythmic detail. I felt Nehring eloquently underlined the grotesqueries and fractured mercurial moods that border on bluff humour at times, which Chopin no doubt intended being a great practical joker in life. The work mysteriously encloses a deeply felt and ardent nocturne in the form of a longing love poem, suffused with a sense of loss. Nehring expressed this dream world and movingly communicated the complexity of these labyrinthine emotions.

Playfulness with hints of seriousness and gravity underlie the exuberant mood of this scherzo. The emotional ambiguities that run like a vein though the work were given heartfelt expression. The central section (lento, then sostenuto) in place of the Trio, gives one the impression so often with Chopin, of the ardent, reflective nature of distant love. Nehring possessed a poignant, beautiful cantabile. The 'triumph and the will' infused the passionate last chords that close the work.

Heinrich Heine, a German poet who idolized Chopin, asked himself in a letter from Paris: ‘What is music?’ He answered ‘It is a marvel. It has a place between thought and what is seen; it is a dim mediator between spirit and matter, allied to and differing from both; it is spirit wanting the measure of time and matter which can dispense with space.’

Mazurkas Op. 56

No. 1 in B

major

Rustic nostalgia expressed here by Nehring within the harmonically adventurous and fragmented nature of this long work. Excellent grasp of the mazurka rhythm.

No. 2 in C major

Ferdynand Hoesick described this mazurka that has such a rustic dance feel as follows: ‘The basses bellow, the strings go hell for leather, the lads dance with the lasses and they all but wreck the inn’. I felt Nehring was convincingly boisterous and rumbustious! Fragments of adolescent memory presented with excellent rhythm.

I always felt this mazurka as not based in reality but in nostalgic dream and memories. I felt Nehring in his thoughtfulness made much of the quite extraordinary and adventurous, even today, 'Eastern' harmonic transitions. This fragile, refined work drifts over the Mazovian plain on a summer breeze, fading away to nothing as an autumn leaf falls into a slow-moving stream...

| |

| The Utrata River in the gardens at

|

Andante Spianato and Grande Polonaise in E flat major Op. 22

The difficulties concealed in the Andante spianato and Grande Polonaise in E flat major Op. 22 (1834–5) are easy to underestimate. Many competitors in the International Chopin Competition have come to grief in this work.

Chopin often performed the Andante spianato (smoothly without anxious tension) as a separate piece in his rare recitals. It has both the character of a nocturne and a lullaby. I felt Nehring perfectly captured the bel canto character and fluid cantabile of the work perfectly with fine tone and refined touch. The tender expressiveness could possibly have been more dwelt upon. There is a deeply affecting simplicity here (as in much of Chopin) which can surely be explored with even more yearning phrasing.

The Grande polonaise brillante with its opening 'Call to the Floor' as if on horns and its super glittering style brillante is such a dramatic gesture! Nehring adopted a declamatory nobility and majestic delivery, proud and valiant, which suited the work brilliantly. Hardly anyone playing Chopin waltzes has any idea of ballroom dancing in the nineteenth century but as a Pole perhaps Nehring could imagine it!

‘Chopinek’ composed his first Polonaise at the age of seven.

The

polonaise breathes and paints the whole national character; the music of this dance, while

admitting much art, combines something

martial with a sweetness marked

by the simplicity of manners of

an agricultural people . . . Our fathers danced it with a marvellous ability

and a gravity full

of nobleness; the

dancer, making gliding steps with energy, but without skips, and caressing

his moustache, varied his movements by

the position of his sabre, of his cap, and of his tucked-up coat sleeves,

distinctive signs of a free man and a warlike citizen.

Chopin in his youth was mad about dancing, a fine dancer and also an excellent dance pianist playing into the small hours, hence his need for 'rehab' at Bad Reinherz – now Dusznki Zdrój. Certainly Chopin waltzes are not meant to be danced but the sublimated idiom remains. Chopin waltzes nearly always open, except say the Valse triste, with an energetic and declamatory fanfare or 'call to the floor' for the dancers. A slight pause and then the scandalous Waltz begins.

The essential nature of the style brilliant, of which the Grand Polonaise Brillante Op.22 is an essential and outstanding representative of Chopin’s early Varsovian style, seems rather a mystery to modern pianists who are not Polish. I felt Nehring in this work conceived of Chopin as a grande maître of the piano which sometimes bordered onthre symphonic but I found it an utterly convincing approach pace the 'authenticists'.

Jan Kleczyński writes of this work: ‘There is no composition stamped with greater elegance, freedom and freshness’. The style involves a bright, light touch and glistening tone, varied shimmering colours, supreme clarity of articulation, in fact much like what was referred to in French as the renowned jeu perlé.

Nehring came quite some way along that road certainly - but there are also vital expressive elements of charm, grace, taste, affectation and elegance to be considered too. The work is a fascinating piece of theatre which perhaps is as this work should be considered in many respects. It is not deeply philosophical but an utterly enjoyable brilliant confection written by a high-spirited young Pole named Fryderyk Chopin, a lover of dancing and acting. One must not forget that Chopin astonished Vienna by his pianism but perhaps even more by the elegance of his princely appearance.

Berceuse in D flat major, Op. 57

This work can surely be considered ‘music of the evening and the night’. The Chopin Berceuse is possibly the most beautiful lullaby in absolute music ever written. The manuscript of this cradle-song masterpiece belonged to Chopin's close friend Pauline Viardot, the French mezzo-soprano and composer. Perhaps this innocent, delicate and tender music was inspired by his concern with her infant daughter Louisette. George Sand wrote in a letter ‘Chopin adores her and spends his time kissing her on the hands’ Perhaps the baby caused Chopin to become nostalgic for his own family or even reflect on a child of his own that could only ever remain an occupant of his imagination.

The Berceuse, composed and completed at Nohant in 1844, appears to constitute a distant echo of a song that Chopin’s mother

sang to him: the romance of Laura and Philo, ‘Już miesiąc zeszedł, psy

się uśpily’ [The moon now has risen, the dogs are asleep].

(Tomaszewski). In view of this tender genesis of infancy, I felt Nehring could have

been a touch more subtle and delicate in touch in order to paint an atmosphere of expressive

innocence. The work hovers hesitatingly between piano and pianissimo.

* * * * * * * * * *

|

| Yulianna Avdeeva |

At 7 p.m. in the Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall, Yulianna Avdeeva, winner of the 16th International Chopin Competition in Warsaw in 2010, gave a truly remarkable and profoundly musical recital.

Programme

Mazurkas Op. 41

|

| Rural danced mazurkas |

I feel the Chopin mazurkas are too often played as if they were existing in present time, describing the present reality of a dance. However, one must remember in many cases they are recalled dances, memories of past joys with a significant weight of melancholic nostalgia. These reminiscences of dance and associated experience are all viewed through the obscuring veils of past time, a musical À la recherche du temps perdu. They cannot be considered in an over-passionate recall or even visceral recreation of experience. Life is simply not like this as the gauze of memory descends

The mazurkas were published as sets and Chopin himself may have had some organisational musical mystique, a musical or philosophical connection in grouping them together in their compositional arrangement in collections. Listening to them I certainly felt as if I was wandering nostalgically along a river bank among the willows in Chopin’s beloved Mazovia, remembering nostalgically happier days or rumbustiously taking part in a village festivity. All these pleasant activities I have engaged in.

The implied improvisatory quality of these pieces, such a fundamental quality of growth in the composition of Chopin’s mazurkas, was always clear.

No. 1 in E minor

The Mazurka in E minor, composed and first played on Majorca, seems to reflect Chopin’s flights of fancy into ‘a land more lovely than the one we behold’.

The piece dates from 1838 at Palma on Majorca, shortly after Chopin and George Sand became residents of the island. The name ‘Palman’ was thus given to this mazurka. The ‘Palman’ was published the year after their return from Majorca as his Op. 41.

Chopin composed mazurkas throughout his brief life. We are made aware the melody of a Polish song about an uhlan (a light cavalryman armed with a lance) and his girl, ‘Tam na błoniu błyszczy kwiecie’ [Flowers sparkling on the common] (the song written by Count Wenzel Gallenberg, with words by Franciszek Kowalski). During the insurrection in Poland it was one of the most popular. Chopin quoted it almost literally, at the same time heightening the drama, giving it a nostalgic, tragic atmosphere. Avdeeva gave the work a rather low, gentle and most expressive dynamic, rhythm and phrasing which was most affecting.

No.2 in B major

This mazurka was most likely

composed at Nohant, although doubts have been raised about this, since it bears

a trace of the sojourn on Majorca. His pupil Wilhelm von Lenz observed that

Chopin felt the opening depict the sound of guitars. This are followed by

oberek dance rhythms. ‘The first four bars and their repetitions’, said Chopin,

‘are to be played in the style of a guitar prelude, progressively quickening

the tempo’

Avdeeva adopted a rather lively, nervous and yet appropriate 'Spanish' tempo.

No.3 in A-flat major

This mazurka brings rhythms and melodies heard in the Cuiavia region of north-central Poland on he left bank of the Vistula River. It has touchingly beautiful, evocative moments which Avdeeva made poignantly expressive. This touching work has a folkloric simplicity and modesty and great subtlety in the piano writing.

No. 4 in C-sharp minor

This mazurka was composed during the first summer at Nohant and published in 1840. It is without doubt one of the most beautiful of the Chopin mazurkas, 'resembling a miniature dance poem' (Tomaszewski). It seems to arise out of nothing, and ends the same way. Stephen Heller (1813-1888 - Hungarian pianist, teacher and composer) wrote perceptively and lyrically : ‘What with others was a refined embellishment, with him was a colourful bloom; what with others was technical fluency, with him resembled the flight of a swallow’. The conclusion or climax celebrates the mazurka sound and rhythm. 'The epilogue brings the music back to the silence whence it issued forth.'

I felt the magnificent keyboard technique that Avdeeva possesses tended to overshadow the femininity and gentle emotions lying at the heart of this work

Scherzo in C sharp minor Op. 39

This scherzo opens in a 'Gothic', almost grotesque manner to become a fine and noble composition, approaching immense grandeur. Dedicated to his muscular pupil Adolf Gutman, this was last work the composer sketched during the Majorca sojourn and in the fraught atmosphere of the monastery at Valldemossa.

The religiosity of the chorale was answered by Avdeeva with an atmospherically particularly meaningful jeu perlé cascades of notes, diamonds falling on crystal. She on occasion approaches this composer as a grand maître which displays her immense musical authority and pianism. I feel this is not always appropriate when plumbing his more thoughtful, introverted, even philosophical nature. Then again, everyone has his own Chopin which he defends to the end.

Yet she expressed the sotto voce transition to the minor in a deeply haunting and existentially tragic manner as humanity faces the abyss of death. Chopin was ill at the time of composition which interrupted and perhaps affected the writing. ‘…questions or cries are hurled into an empty, hollow space – presto con fuoco.’ (Tomaszewski).

Barcarolle F sharp major Op. 60

|

| Venice by J.M.W. Turner |

The work

is a charming gondolier’s folk song sung to the swish of oars on the

historic Venetian Lagoon or a romantic canal, often concerning the travails of

love, a true song of love. It is a grand, expansive work from the late period

of Chopin, written in the years 1845–1846 and published in 1846. Chopin refers

in this work to the convention of the barcarola – a song of

the Venetian gondoliers which inspired many outstanding composers of the

nineteenth century, including Mendelssohn, Liszt and Fauré. Yet surely Chopin's Barcarolle is

incomparable…

As with the Berceuse, Op. 57, the work may be considered ‘music of the evening and the night’ (Tomaszewski). However, it is a far longer work and of immense difficulty. The work is not a contemplative nocturne although there are similarities – it explores many passions of the day and the night. The penumbra of eroticism, Venice and the nature of Italian passions present in the ornamentation, is strongly present in this masterpiece with its universal emotions.

Avdeeva showed great sensitivity to nuances in her approach and handled the aesthetic fluctuations of mood with formidable intensity, creating both passion and a charming water colour of the rather contemplative yet often fraught, contrasting emotions of romantic love on the poetic lagoon.

Polonaise-Fantasie in A flat major Op. 61

Again I make

no apology for repeating my introduction to this and other works as such

background facts do not change, although the interpretative approach by various

pianists is always completely different.

For me this was by far the most successful conception and profound interpretation of her Chopin recital.

The Polonaise-Fantaisie contains all the troubled emotion and desire for strength in the face of the multiple adversities that beset the composer at this late stage in his life. This work, the first in the so-called ‘late style’ , was written during a period of great suffering and unhappiness. He laboured greatly over its composition. What emerged is one of his most complex works both pianistically and emotionally.

Avdeeva wrestled passionately with the work in a like manner to the composer with a marvelously 'searching' improvisation in the opening before embarking on the musical substance of the piece proper. The work had a feeling of being sought for harmonically and then some direction at least discovered, first as a type of improvisation and then with increasing self-confidence. Avdeeva has a gifted ability to communicate such difficult, transient existential emotions.

Chopin produced many sketches for the Polonaise-Fantaisie and

wrestled with the title. He had written: ‘I’d like to finish something

that I don’t yet know what to call’.

This uncertainty of direction in the writing surely indicates he was embarking on a journey of compositional exploration along untrodden paths. Even Bartok one hundred years later was shocked at its revolutionary nature. The work is an extraordinary mélange of genres and styles in a type of inspired invention that yet maintains a magical absolute musical coherence and logic. He completed it in August 1846. Avdeeva utilized silence in a soulful manner, often touching the heart with poetic lyricism on many occasions.

The opening tempo is marked maestoso (as with his two concerti) which indicates ‘with dignity and pride’. The invention fluctuates as if with the irregular circulation of the heart and the blood. Avdeeva embraced the emotive gestures and power of these silences in her phrasing and rubato, investing the structure with much musical meaning. One must possess a true empathy for these imagined conflicts and deprivations. This considered musical narrative was most expressive.

The music in

such a work must come from ‘within’ rather than overlaid ‘on top’ as it were.

There are so many emotional implications that must be indicated with subtlety

and finesse. Towards the conclusion we move haltingly and with suffering from

despair to final resignation. The periods of introspection are intense but

short.

Avdeeva with glowing tone finely conceived of the rich counterpoint and polyphony to be explored here (of which Chopin was one of the greatest masters since Bach). This work also conveys a strong sense of żal, a Polish word in this context meaning melancholic regret leading to a mixture of passionate resistance, resentment and anger in the face of unavoidable fate. Avdeeva understood this emotion well from her many years of familiarity with expressing it in Chopin's compositions.

Yes, a highly complex work poignantly expressed by Avdeeva as a true fantasy of shifting soundscapes, written when Chopin was moving towards the cold embrace of death.

INTERMISSION

Much history,

landscape and the present cruel and barbarous conflagration was coursing

through my mind as I listened to Chopin's compositions which speak so

eloquently of suffering and anguish.

The great pianist and statesman Ignacy Jan Paderewski said in an eloquent address given at the Chopin Centenary Festival at L’viv (Lemberg, Lwów) in 1910:

‘He gave all back to us, mingled with the prayers of broken hearts, the revolt of fettered souls, the pains of slavery, lost freedom’s ache, the cursing of tyrants, the exultant

songs of victory.’

Fryderyk Chopin,

while ‘detached’ from the Polish revolutionary cabals in nineteenth century

Paris, expressed more profoundly than almost any composer the universal

suffering of any and all spirits labouring under a

totalitarian heel or shackled by personal psychological chains. His music

offers deep consolation to troubled and tormented hearts throughout

the world. The music of Chopin continues to express the beauty and richness of

our conscious life, forever overshadowed by the implacable reality of brutality,

death and evil, a profound awareness and rejection of which is surely the

source of all we would wish to call ‘civilization’.

I could not

help reflecting how the expression of the powerful spirit of resistance

in much of Chopin is so desperately needed today, strengthened by with the

powerful arm of his universality of soul. We are confronted throughout the

world by incomprehensible onslaughts of evil, barbarism, the self-serving

politics of war. Financially we gaze upon the dance around the golden calf

depicted in the Old Testament.

The spirit of Chopin is impregnable. His universality lies in his profound sense of loss and nostalgia. His revolutionary music expresses a fierce resistance to domination, a sense of sacrificial melancholy in the face of the bitter finales of life – universal and timeless human emotions. We need Chopin, his heart and spiritual force in 2023, possibly more than ever.

Ferenc Liszt

|

Franz Liszt at an advanced age |

Although the music of the second half of her carefully assembled recital was not that of Chopin, I felt Avdeeva had in many ways dedicated it entirety to the magnificently courageous and valiant defenders of Ukraine. The dark and harmonically exploratory moods created by Liszt in his late pieces suited the melancholy that has descended like a miasma of memories over present day Europe.

Vladimir Nabokov observed that great books required great readers. In an analogous manner, in the case of the late works of Franz Liszt, great music requires great listeners.

Liszt once told Princess Carolyne in a much quoted sentence that his only remaining ambition as a musician was to 'hurl my lance into the boundless realms of the future.'

Carolyne added the observation: 'Liszt has thrown his lance much further into the future [than Wagner]. Several generations will pass before he is fully understood.' (quoted in Franz Liszt Volume III The Final Years 1861-1886 Alan Walker p.455). These astonishing late works were seeds and catalysts for Bartók and Schoenberg, even the twelve tone row which Liszt envisioned.

In 1881 Liszt was struggling with ill health and depression exacerbated by an accidental fall down the stairs at his school Hofgärtnerei in Weimar.

|

| Hofgärtnerei in Weimar |

|

| Franz Liszt in Weimar in the 1880s |

Bagatelle sans tonality (Bagatelle Without Tonality) S 216a

The title was given this quite extraordinary piece in 1885 by Liszt himself. The work indicates his fascination with his increasingly exploratory, atonal harmonic 'experiments'. Avdeeva presented it superbly as an impressionistic tone painting reminiscent of the later composer Debussy. At the time, any hearing of a performance created unease in listeners (even gifted ones) but our more experienced ears render the sound world completely acceptable and astonishingly beautiful. His pupil Hugo Mansfeldt played it, rather secretly, at his debut recital in Weimar the same year as the composition. He was gratified that the work had only been played by himself and Liszt

Unstern! Sinistre, Disastro S 208

The associations of a destiny condemned to suffering were clear from the outset of tritones or 'the devil in music'. Avdeeva played this petrifying piece in the most terrifying and ominous manner possible. A magnificent re-creation The connotations of the present war, death and extreme suffering could not have been clearer. I found the work played by Avdeeva deeply haunting, The conclusion had a feeling of the withering expiration of life as it resolves on an unfulfilled sub-dominant, fading with existential inevitability into a profound use of silence, rendered here as important structurally as sound.

Schopenhauer wrote of the difference between 'talent' and 'genius'. 'Talent is like a marksman who hits a target the others cannot reach; genius is like a marksman who hits a target the others cannot even see.' The conclusion concerning Liszt as a composer of genius is transparent. Liszt once observed 'I calmly persist in staying stubbornly in my corner, and just work at becoming more and more misunderstood.'

Légende No. 2 St Francis of Paola walking on the waves S 175

From childhood Franz

Liszt was always genuinely religious and possessed patron saints. He venerated Francis of Assisi

(1182–1226) and the Franciscans. Adam Liszt, his father, introduced him to the

friars. He made many visits to the Franciscans in Pest in Hungary and finally applied

for admission as a tertiary member. This request was honoured in 1857 and on 11

April 1858 he was ordained as a confrater. In 1868 Liszt made a

pilgrimage to Assisi.

However the

saint that most attracted him was Francis of Paola (1426-1507).He was a

Franciscan monk and a founder of the eremite Franciscan order known as the

Minim Friars. Francis of Paola’s motto was 'Caritas!' or the compassionate

love, assistance, and care of the deprived in life. This suited the temperament

of the ever generous Liszt who lived not a life a life of luxury befitting a

famous composer, but more one of denial for others. These

two saints inspired Liszt to compose various vocal and instrumental works. The two Legends for piano are programmatic pieces

in which Liszt chose to present in music one episode of their lives.

The words below of Liszt's prayer to St. Francis were written by his pupil Martha von Sabinin, the daughter of the Russian Orthodox priest in Weimar, who had herself taken holy orders and had meanwhile become the abbess of the Order of the Annunciation in the Crimea. Liszt had a drawing of Steinle's drawing of St. Francis of Paola hanging in the music room at the Altenburg in Weimar. (from Franz Liszt Volume III The Final Years 1861-1886 Alan Walker p.360 n).

How relevant this detail is to the present fraught and brutal international situation.

|

The painting of Saint Francis of Paola crossing the

Strait of Messina on his cloak in the Chiesa di San Francesco da Paola

by Charles-Claude Dauphin (1615 – 1677)

Liszt included this poem at the head of the manuscript:

St. Francis!

You walk across

the ocean storm

And are not

afraid

In your heart

is love, and in your hand a glowing ember

Through the

clouded heavens God's light appears

Liszt's

preface to the second legend reads:

Among the numerous miracles of St. Francis of Paola, the legend celebrates that which he performed in crossing the Straits of Messina. The boatmen refused to burden their barque with such an insignificant-looking person, but he, paying no attention to this, walked across the sea with a firm tread. One of the most eminent painters of the present religious school in Germany, Herr Steinle, was inspired by this miracle, and in an admirable drawing, the possession of which I owe to the gracious kindness of the Princess Caroline Wittgenstein, has represented it, according to the tradition of Catholic iconography:

St. Francis standing on the surging waters; they bear him to his destination, according to the law of faith, which governs the laws of nature. His cloak is spread out under his feet, his one hand is raised, as though to command the elements, in the other he hold a live coal, a symbol of the inward fire, which glows in the breasts of all the disciples of Jesus Christ; his gaze is steadfastly fixed on the skies, where, in an eternal and immaculate glory, the supreme word "Charitas", the device of St. Francis, shines forth.

In her performance Avdeeva was truly noble and majestic, monumental in the manner of a Romanesque basilica, investing the work with profound religious gravitas, deep feeling and expressiveness. So many great virtuosos such as Horowitz use the work as a tempestuous display piece of breathtaking keyboard command. I felt this not to be the case with Avdeeva who resisted this almost irresistible temptation.

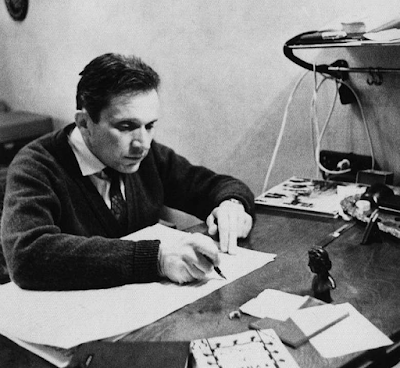

Mieczysław Weinberg

|

| Mieczysław Weinberg (1919-1996) |

There is a definite Renaissance in Polish music taking place at present as great works are being discovered and recovered especially as a result of the unremitting efforts of National Fryderyk Chopin Institute. Their many new recordings are an Aladdin's cave of precious compositions.

The notion of an 'Iron Curtain' that divided Europe after WW II was created by Winston Churchill in a speech at Fulton, Missouri, on 5 March 1946. One all too easily forgets that 'the curtain' was a cultural as well as political barrier with immense musical and artistic implications preventing any rich and creative cross-border symbiosis and fertilization.

The music of Mieczysław Weinberg (1919–1996) is among some of the 20th century's greatest hidden treasures. Born in Poland, Weinberg emigrated to Russia in perilous circumstances, where he was to live out the rest of his days half-way between deserved fame and unjustified neglect. Often seen in the shadow of his close friend Dimitry Shostakovich, by whom he was regarded as one of the most outstanding composers of the day, Weinberg is slowly being rediscovered as a 20th century genius, a figure of immense significance in the landscape of post-modern classical music.

Weinberg's musical idiom stylistically mixes traditional and contemporary forms, combining a freely tonal, individual language inspired by Shostakovich with ethnic (Jewish, Polish, Moldovian) influences and a unique sense of form, harmony and colour. His prolific output includes no less than 17 string quartets, over 20 large-scale symphonies, numerous sonatas for solo stringed instruments and piano as well as operas and film-scores. With the constant stream of recordings, score publications and concerts over the last decade, many of these gems have been unearthed to finally receive the critical praise and attention they deserve.

(Copyright © www.music-weinberg.net (2002 – 2023) Full information about Weinberg and his voluminous works in available on this link.

From film and circus music to tragic grand opera, from simple melodies with easy accompaniments to complex twelve-tone music, he was a master of all forms, genres and stylistic directions. With virtuosity and elegance, but always judiciously and with balance, he used elements of Jewish, Polish, Russian and Moldavian folk music. He developed a very personal style with a clear, almost classical architecture. His melodic language – at times introverted and meditative-reflective, at other times full of effervescent joy of living – is particularly noted for its special richness. (Ulrike Patow Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: Allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik (MGG) Vol. 17, p. 688ff)

Piano Sonata No. 4, Op. 56

Weinberg was an accomplished pianist but his piano sonatas only span the early and middle periods of his career. The Russian musicologist Lyudmila Nikitina observed: '... the idea of universal harmony, the unity of all that exists, is key to understanding the characteristics of Weinberg's style, its neo-classical and neo-romantic orientation.'

Allegro

I found this movement with Avdeeva light with an affecting minimalist elegance. Yet it was a tremendous, eloquent statement of resistance to oppression.

Allegro

I found this a magnificent movement in its rather neurotic dislocation and fragmentation.

Adagio

Here was such gentle, lyrical internal contrast to what had passed before. Avdeeva created abstract dreams and poetry that merge with humanity but only at times, one might say this music expresses 'suffering with love'. An harmonic exploration of the existential forest.

Allegro

I found this movement rather affectingly and warmly Jewish in its harmonic palette with its Eastern dance rhythms and dense polyphony. The movement was full of suppressed anger against the granite of destiny.

In this sonata Avdeeva gave us a convincing, virtuosic, emotional and deeply moving tribute to valiant Ukraine. Her performance was also a formidable account of undoubted magnificence of a piano composition by a neglected composer whom many describe as the third great Soviet composer after Shostakovitch and Prokofiev.

| A video of her magnificent playing of the Chopin 'Heroic' Polonaise in A-flat major Op.53 at this recital is available here courtesy of the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute, Poland https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TIa5MlCTITQ |

A fascinating interview with Yulianna Avdeeva and Aleksander Laskowski of the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute is available here

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R0Rt0t40OD4

It's inspiring to see the celebration of Fryderyk Chopin's birthday through music in this post. Michael Moran's passion and knowledge of Chopin's music is evident in his performance and commentary. The selection of pieces is both diverse and appropriate for the occasion, and the execution is commendable. As someone who appreciates classical music, I find this post to be a wonderful tribute to one of the greatest composers in history. It's heartening to see that even in 2023, Chopin's music continues to be celebrated and enjoyed by musicians and music lovers alike. Overall, a delightful and enjoyable read/listen. I also remember that the Music Production Courses in Bangalore also provides a professional service similar to this.

ReplyDelete