A Brief Respite from War - Aleksandra Świgut records a superb 'Real Chopin' CD played on a fine 1858 Erard piano

This is an outstanding disc of the immortal music of Chopin, played by the exceptionally deep-souled and inspired musician Aleksandra Świgut. The pieces are performed on a seductive, sweet-toned, refined and colourful 1858 Erard prepared and tuned to perfection of sound by the great piano builder Paul McNulty.

One reason I admire the playing of Aleksandra Świgut is her unique voice, her individuality, spontaneity and the resulting surprising contrasts. She often astonishes me and makes unpredictable but creative interpretative gestures in her rather theatrical approach to music. I was interested in how she would approach Chopin on this historical instrument although I recognize her unique mastery of such period pianos.

It is a fascinating and inspiriting experience as a listener to follow the development of a young pianist through the inevitable passage of time. For many years now I have followed her developing musical career in addition to the expanding intellectual depth of character and sensibility of this young pianist. This disc is a testament to a musical achievement of a high order.

I wrote in an early review:

She was always a distinct personality that stood out and her choice of programme indicates she has very clear ideas of what she loves to play. The absolute joy and delight in playing this music that suffused her features was quite affecting – the profound pain, sweat and suffering that produces the usual anguished countenance and distorts the face of many young pianists was mercifully absent !

Among many prizes and awards, she was awarded the ex aequo 2nd Prize at the 1st International Chopin Competition on Period Instruments 2–14 September 2018. This award becomes increasingly justified as we listen to her command of the 1858 Erard.

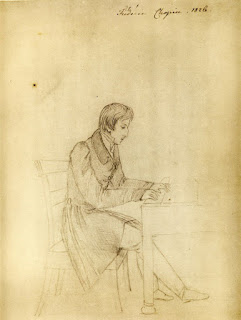

Variations sur “Là ci darem la mano” B flat major op. 2

|

‘Là ci darem la mano’ Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942) (National Trust, Fenton House, Hampstead, London) |

The youthful Chopin Variations in B-flat major on ‘La ci darem la mano’ from Don Giovanni is an early masterpiece. Mozart and his immortal music (a Chopin passion) was bound to survive in this rejuvenated capital of a country that once did not even appear on European maps but was merely a state of mind within the psyche of its former national inhabitants.

Warsaw is no great distance from Vienna and Mozart's wildly popular 'absolute hit' Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) was produced in May 1783 by a touring German company for the birthday of King Stanisław Augustus just ten months after the Vienna première. Don Giovanni arrived in the capital to play in the National Theatre before the king in October 1789 with the same Italian Domenico Guardasoni company that had premièred the opera just two years before in Prague with Mozart conducting. His operas were performed in Warsaw well in advance of Berlin, Paris or London. The city has had a distinguished operatic heritage since the early baroque period when it was the only capital other than Rome to have had an opera theater that hosted famous Italian soloists.

Chopin composed the ‘Là ci darem’ Variations in 1827. As a student of the Main School of Music, he had received from his teacher Jósef Elsner a compositional task: to write a set of variations for piano with orchestral accompaniment. As his theme, he chose the famous duet between Zerlina and Don Giovanni from the first act of Mozart’s opera Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni.

Chopin was seventeen when he composed this style brillant virtuoso work for piano and orchestra. The influence of Hummel and Moscheles is clear (Chopin greatly admired Hummel's playing as did the rest of Europe! His joyful, untroubled music is still undeservedly neglected. Audiences were said to stand on their chairs to see how Hummel accomplished his trills. Now that does not happen today!) Although originally conceived for piano and orchestra, its popularity soon led to a solo piano version of immense executive difficulty ! The piano was an evolving instrument and each new development created great excitement among composers of the day. Chopin as a youth haunted the Polish piano factory of Fryderyk Buchholtz in the role of what we might term an ‘early adopter’.

In this opera overwhelming power and faultless seduction meet maidenly naivety and barely controlled fascination. (Mieczysław Tomaszewski)

In his famous first review of Chopin’s variations on Mozart’s ‘Là ci darem la mano’, Schumann gives us a striking description:

'Eusebius quietly opened the door the other day. You know the ironic smile on his pale face, with which he invites attention. I was sitting at the piano with Florestan. As you know, he is one of those rare musical personalities who seem to anticipate everything that is new, extraordinary, and meant for the future. But today he was in for a surprise. Eusebius showed us a piece of music and exclaimed: ‘Hats off, gentlemen, a genius! Eusebius laid a piece of music on the piano rack. […] Chopin – I have never heard the name – who can he be? […] every measure betrays his genius!’'

Chopin’s ‘Là ci darem’ variations are classical in form with an introduction, theme, five variations and finale. They are a marvellous example of the style brillant and clearly influenced by Hummel and Moscheles.

Clara Wieck loved this work and performed it often making it popular in Germany. Her notorious father, who had forbidden her marriage to Robert Schumann, wrote perceptively and rather ironically of this work:

‘In his Variations, Chopin brought out all the wildness and impertinence of the Don’s life and deeds, filled with danger and amorous adventures. And he did so in the most bold and brilliant way’.

Świgut opened the long Introduction in an almost improvisatory manner suffused with gentle irony and ominous moments of tragic threat and drama as if feeling her way into the famous ‘Là ci darem’ aria. In the Variations that followed she applied rubato and phrasing that was musically perceptive, almost as if the aria was being sung with vocal intonation and an alluring and charming cantabile. There was an overriding sense of insidious seduction overlaying the misleading innocence however. Her technique in the following Variations created on the Erard a scintillating example of style brillant ornamentation and glittering acoustic delight. Świgut brought us a sense of theatre, humorous human weakness, the pernicious attractiveness and insidious persuasiveness of the Don and Zerlina's vulnerability to the nature of 'love'. Such expressive features she brought to bear fitted this remarkable and precocious Chopin work immeasurably well.

Scherzo in C sharp minor, Op. 39

This scherzo opens in a 'Gothic', almost grotesque manner to become a fine and noble account of the work approaching grandeur. Dedicated to his muscular pupil Adolf Gutman, this was the last work the composer sketched during the Majorca sojourn and the fraught atmosphere of the monastery at Valldemossa. The religiosity of the chorale is answered with a meaningful jeu perlé cascades of notes, diamonds falling on crystal or a rushing mountain stream. Frederick Niecks quotes Robert Schumann who wrote of the Chopin Scherzos (the Italian word scherzo meaning 'joke') 'How is 'gravity' to clothe itself if 'jest' goes about in dark veils?'. .

‘…questions or cries are hurled into an empty, hollow space – presto con fuoco.’ (Mieczysław Tomaszewski).

Świgut delineated the complex character of this scherzo by utilizing the wide colour spectrum and timbre palette possible on the Erard. Her expressive articulation and contrasts lifted this work into an elevated realm of spiritual reference. The sotto voce transition to the minor on this instrument was effectively haunting and existentially tragic, evoking the abyss of death. A gesture of defiance concludes the work. Do not go gentle into that good night (Dylan Thomas). Chopin was ill at the time in Majorca which interrupted and may have affected the writing. Świgut created a sense of emotional ambiguity present at the centre of Chopin's energetic despair.

Contredanse in G flat major (WN 27)

The Country Dance in G flat major ascribed to Chopin was discovered and published in 1934. Its authenticity is not certain as the extant manuscript is not in the composer’s hand. (NIFC) With her instinctive charm and gracefulness Świgut interprets this country dance almost as if it was a seduction dance by Don Giovanni of Zerlina, soft words and gentle gestures whilst beneath the civilized behaviour there lurks goodness knows what! The Polish ethnologist Oskar Kolberg noted that the suggestive figures of this dance in turn ‘drew the dancers together, then moved them away from each other. Joined them, then separated them’.

Barcarolle in F sharp major, Op. 60

.jpg) |

| Bacino di San Marco, Venice - J.M.W. Turner The Dogano, San Giorgio, Citella, from the Steps of the Europa (exhibited 1842) |

Although a tremendously fine performance on every musical and pianistic level, I am afraid I did not warm so strongly to this interpretation, this conception of the Barcarolle. For me the work is a charming gondolier's folk song sung to the swish of oars on the historic Venetian Lagoon or perhaps a romantic canal concerning the mercurial travails of love.

The love tryst, perhaps on a gondola, cannot begin with too heavy an opening octave as the lovers set off on their excursion from the quay (perhaps the Molo). I feel Chopin intended merely to delicately set the tonal landscape of the work, like a watercolour wash, against which the drama unfolds. There is no accent on the autograph Stichvorlage in the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków.

|

| Chopin autograph Stichvorlage of the Barcarolle lodged in the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków |

It is the scale and relative dynamics that are also important here. Chopin's dynamics should be considered at a lower than indicated level, one step lower than might be indicated to the modern 'Steinway ear'. The composer himself played the work in a number of vastly differing ways if reports are to be believed, sometimes forte and on one occasion the whole work located between piano and pianissimo. Excessive, even painful, dynamic inflation is simply not possible on period pianos.

Taking a voyage across the Venetian Lagoon in a real gondola (although a frightful cost these days) is a very educational experience in how to approach this work. No, not a fanciful idea at all. I once attended a performance of Liszt’s symphonic poem Tasso, Lamento e Trionfo at a concert in Budapest. The organizers had actually brought a real singing gondolier from Venice in full costume to at first sing the original theme on which Liszt based his work before the symphonic poem itself was played. Liszt used the theme of the song of the gondolier "La Biondina in Gondoletta" (loosely: the blonde in the gondola) by Giovanni Battista Peruchini in his piano work Venice and Naples from the Deuxième Année de pélerinage: Italie and later in this symphonic transformation. A fascinating and imaginative idea by the concert organizers in Budapest.

As the piece progressed, I felt Świgut approached this work more as a pianistic virtuoso composition with slightly restricted romantic expression and emotional content. I imagine everyone conceives of the work differently depending on their life experience. Everyone has their own Chopin !

It is a profound work that explores the 'moving toyshop of the heart' (Alexander Pope). In my conception of the work, I have a view that has less pronounced dynamic contrasts, rather more resembling lyrical romantic poetry. The rocking motion of the gondola or skiff painted by her left hand was delightfully sustained throughout. The lyrical narrative of serene sentiment is followed by troubled love, even a tumultuous argument erupts on this romantic outing. The highly passionate conclusion verges on the overwhelming but the floods of ardor fade into the mists that finally settle into the damp night as will-o’-the wisps come out to dance on the waters and the lovers fall asleep….

As always, once more I am taken over by literary associations that evoke visions listening to Chopin's Barcarolle. The immortal English poet Robert Browning (1812-1889) loved Venice and lived there for a time. From his bed-room window in the Palazzo Giustiniani Recanati, every morning in 1885, he watched the sunrise.

"My window commands a perfect view," he wrote, "the still, grey lagoon, the few seagulls flying, the islet of San Giorgio in deep shadow, and the clouds in a long purple rack, from behind which a sort of spirit of rose burns up, till presently all the rims are on fire with gold.... So my day begins."

His poem In a Gondola (1896) is a lyric dialogue between two Venetian lovers who have stolen away on a romantic tryst in a gondola in spite of the hovering love assassins known as "the three" who oppose their love - 'Himself' (perhaps her husband), Paul and Gian, her brothers, whose vengeance discovers them at the end. This is not before their love and danger have sufficiently moved them to weave a series of lyrical fancies, and led them to a climax of emotion which makes life shipwrecked in each other's arms so deep a joy that Death is of no account.

Here is a small relevant quotation from In a Gondola. The poet's heroine, while reclining with her lover in their gondola, ponders his death:

She replies, musing.

Dip your arm o'er the boat-side, elbow-deep,

As I do: thus: were death so unlike sleep,

Caught this way? Death's to fear from flame or steel,

Or poison doubtless; but from water--feel!

|

| E. W. Haslehust BROWNING'S HOUSE IN VENICE. Mazurkas Op. 67 |

Each of the mazurkas has an individual poetic feature,

something distinctive in form or expression

(Robert Schumann in a review, 1838)

The mazurkas are famous dance miniatures written by Fryderyk Chopin who wrote fifty-seven of them. Together with the polonaises, they are the most intensely 'Polish' in character of his compositions. There would be no mazurkas without Polish folk dances and Polish folk music. Chopin created stylized, sublimated models with a deep feeling and understanding of the traditional, national, authentic folk music of Poland.

He composed mazurkas from youthful days until his death. Chopin referred to these small works as his ‘heart’s sanctuary’. The pianist requires ‘at the same time an almost naive freshness and a mature mastery’ (Mieczysław Tomaszewski).

When making the first recording (1938-1939) of the complete set of mazurkas, the Chopin interpretative master of the piano, Arthur Rubinstein, demonstrated the steps of Polish folk dances to the record producers in the studio. The great pianist Garrick Ohlsson believes all pianists who perform these works should learn to dance the mazur !

Chopin gestured in this genre towards three folk dances which he knew well as a young man from his many visits and holidays with his family in the Polish countryside. They are the mazur, the kujawiak and the oberek. All possess characteristic rhythms and produce different emotional and physical evocations in the 'dancer', although his mazurkas are not intended as music to actually be physically danced.

|

| The Officers' Ball by the amateur artist and Cavalry Officer (26th Pułku Ułanów) Tomasz Kucharski 1920 |

Mazurka in G major Op. 67 No. 1

This mazurka dated 1835, was written into the album of Miss Anna Młokosiewicz of Warsaw. It is thought Chopin inscribed it in Karlovy Vary, where the young lady was taking the waters with her father, a general, and Chopin had come to spend some time with his parents. Julian Fontana published this Mazurka among Chopin’s posthumous works, placing it at the head of the Op. 67 Mazurkas.

Perhaps it was intended more for dancing than for listening. Chopin's sister Ludwika often mentioned in her letters how those at home in Warsaw often danced his mazurkas, to which he objected in answer! This mazurka in G major, although transcribed in Karlovy Vary, was composed possibly in Vienna, during the long idle summer of 1831, or perhaps even earlier, in Warsaw (Mieczysław Tomaszewski).

Świgut gave the work a highly infectious, emphatic rumbustious rhythm which underlined the possibly physical dancing intentions behind this mazurka.

Mazurka in G minor Op. 67 No. 2

The expression of sadness, reflection or regretful recollection marks the two mazurkas considered to be Chopin’s last: the G minor and the F minor, published by his loyal amanuensis Julian Fontana among the posthumous works.

Chopin wrote to Wojciech Grzymala: ‘I feel alone, alone, alone – though surrounded’.

In 1848 he gave his last Paris concert, at the Salle Pleyel,

and gave a concert tour of England and Scotland, organized by Jane Stirling. He

wrote melancholically: ‘The world has

somehow passed me by. Meanwhile, what has become of my art? And where did I

squander my heart?’

It is considered that the G minor Mazurka was written after Chopin's return from Scotland, in the winter of 1848 or the spring of 1849.

Świgut rendered this simple yet affecting melody with great poignancy, ravishing cantabile and a yearning remorsefulness. Chopin often asserted that 'simplicity' in the interpretation of his mazurkas was the key that unlocked the emotional life lying secretly within. Dark shadows glide over the life that remains. Świgut adds her own improvised period ornamentation to great expressive effect.

Mazurka in C major Op. 67 No. 3

The

manuscript of the Mazurka in C major came into the possession of a Mrs Hoffman,

as we know from the list of unpublished works drawn up by Chopin’s

sister, Ludwika. It was long believed that the person in question was the

well-known writer Klementyna, née Tańska, a friend of the Chopins. Today,

however, we know that another Mrs Hoffman must also be considered, namely

Adelina. She was the proprietress of a ladies’ fashion shop on Krakowskie

Przedmieście Street in Warsaw. On the list of Chopin’s loftily-titled lady

dedicatees, she occupies a distinguished place. The C major Mazurka dedicated

to her flows smoothly along in the swaying rhythm of a songful kujawiak (Mieczysław

Tomaszewski).

In this mazurka, the Erard under such comprehending Polish musical fingers,

reveals itself to be an instrument that lends itself to refined colour,

touch, tone, and timbre. Świgut captures the delicate sentimentality and

regretful recollections contained within this simple yet moving melody. Wonderful to absorb.

Piano sonata in B flat minor Op. 35 (1839)

'The Sonata

in B flat minor, Op. 35, composed in the summer of 1839 at Nohant, was

published in Paris and Leipzig in the spring of the following year. It was not

furnished with any dedication. This is quite understandable: it would be

difficult to dedicate a sonata with a funeral march to anyone. It was written

under the roof of George Sand and under her tender and solicitous care. But, as

we know, Chopin did not consider it suitable to ‘publicly’ offer Mrs Sand –

through an editorial dedication – any of his works. He separated the intimate

domain from the public domain quite radically.

Nevertheless,

it seems unquestionable that personal experiences were written into the music

of the B flat minor Sonata, which arose around a Funeral March inspired by

patriotic sentiment. It is heard and felt like some testimony to the extreme

situation in which Chopin found himself at that time and in that place. The

Sonata was written in the atmosphere of a passion newly manifest, but frozen by

the threat of death. In the times of Mieczysław Karłowicz, it might have been

called a ‘Sonata of love and death’. It became a ‘soliloquial’ utterance – an

inward conversation about existential matters.'

Grave doppio movimento

Scherzo

Marche funébre

Finale Presto

|

| Le Maison de George Sand, Nohant |

He additionally perceptively describes the general mood of this sonata : ‘The Sonata was written in the atmosphere of a passion newly manifest, but frozen by the threat of death.’ A deep existential dilemma for Chopin speaks from these pages. The pianist, like all of us, must go one dimension deeper to plumb the terrifying abyss that this sonata opens at our feet.

From the outset I felt this account was going to be a uniquely moulded, personal existentialist vision of the entire work from an expressive mature artist, a vision that had engaged much thought and analysis. Chopin created a work that is considered to be one of the greatest masterworks of the nineteenth century Western keyboard literature.

George Sand wrote in The Story of My Life :

‘His creativity was

spontaneous, miraculous. He found it without seeking it, without expecting it.

It arrived at his piano suddenly, completely, sublimely, or it sang in his head

during a walk, and he would hasten to hear it again by recreating it on his

instrument.’

[...]

‘But then would begin the most heartbreaking labor I have ever witnessed. […] He would shut himself up in his room for days at a time, weeping, pacing, breaking his pens, repeating or changing a single measure a hundred times, writing it and erasing it with equal frequency [here the writer seems to have got carried away], and beginning again the next day with desperate perseverance. He would spend six weeks on a page, only to end up writing it just as he had done in his first outpouring.’

In the disturbing opening of this sonata, it is vital to establish the focus as a funereal utterance or announcement - Grave. Doppio movimento (twice as fast as the preceding). In this movement Świgut possessed great expressiveness, tremendous energy and forward momentum which gave the approach to this movement, with its lyrical reflections, a type of fatalistic, despondent inevitability. A rider, occasionally in a reflective even nostalgic mood, may be galloping inexorably and passionately towards his lover or his doom. She allowed the music to breathe which is rare. Music is a language that must retain decipherable meaning.

We needed some chiaroscuro painterly effects as we move into the energetic and fairly bizarre Scherzo. Mieczysław Tomaszewski commented on this movement: ‘…one might say that it combines Beethovenian vigour with the wildness of Goya’s Caprichos.' The Trio that emerges after the 'demonic' opening, did truly sing under the fingers of this Polish pianist as if it was an aria lifted from an opera - a genre of which Chopin was passionately fond, especially Bellini. This deeply expressive Trio contained a caressing and heart-warming cantabile. Then again the return of the anxiety of briefly resuscitated life leading directly into the notes of a funeral march. Świgut achieved all of this.

‘When I was playing my Sonata

in B flat minor amidst a circle of English friends, an unusual experience

befell me. I executed the allegro and scherzo more or less correctly [Chopin

was always self-critical] and was just about to start the [funeral] march, when

suddenly I saw emerging from the half-opened case of the piano the cursed

apparitions that had appeared to me one evening in the Chartreuse [on Majorca].

I had to go out for a moment to collect myself, after which, without a word, I

played on’.

(Chopin to Solange from Scotland, Johnston Castle, 9 September 1848)

The Marche funèbre was most impressive with the funeral bell tolling lugubriously in the left hand. Świgut began at a moderate, dignified tempo that grew out of the pessimistic conclusion to the Scherzo. She presented the Marche funèbre as affectingly fatalistic and tragic. This was also true of the contrasting cantabile of the Trio which, as was suggested to me, there is a touch of the unhinged mind as in Act III of Lucia de Lammermoor. The reflective Trio of the Marche funèbre is a contrast of innocence, love and purity blighted, encircled by the reality of death (Chopin was terrified of being buried alive – often horrifyingly possible in those primitive medical times).

Świgut adopted a properly eloquent tempo and dynamic, so difficult to achieve in this movement. Many listeners and pianists seem to think it ought to accompany an imaginary military band approaching or departing a cemetery with a heavy dull tread of boots, lacking in poetry. She played piano to pianissimo at times with intense poetry and a singing tone.

With Świgut the Trio that interrupts the leaden tread of the Marche funébre, brought a lyrical contrast of poignant reflection on the nature of love. In the face of the profound grief of the Marche, the fragility of the joys of life, the ruthless pendulum of fate and death, needs to be feelingly communicated to us, as was so accomplished by Świgut. The brief return of the gloomy theme of the inevitability of death was unsettling at a piano dynamic. I felt a deep and haunting melancholy in this movement, a forlorn cry of the human soul facing its inevitable destiny.

The innocence of the Trio was movingly expressed with sensitive cantabile in tone colour and touch. Świgut with her touching, beautifully singing cantabile on the Erard, conceived the central section of the movement as a superb operatic yet tender bel canto aria, a simple and naive utterance until the inevitable fatalistic return of the Great Reaper, surprisingly soft in dynamic and therefore even the more deeply despairing.

The Finale Presto seemed appropriately unhinged expressively by grief. Świgut created the polyphonic transparency most effectively with minimal use of the pedal. Chopin wrote characteristically with intentional irony of the movement evoking ‘chattering after the march’ leaving Schumann to write in philosophical and literary frustration: ‘The Sonata ends as it began, with a riddle, like a Sphinx – with a mocking smile on its lips’.

The polyphony, influenced by Bach whom Chopin adored, is transfigured by Świgut, highlighted by the harmonic complexity lying within the fragmented, besieged mind of death's witness. The waves within a grief-stricken mind written in baroque counterpoint recall a more optimistic yet fatally ominous past.

Overall Świgut gave us a coherent, integrated personal view of the work that indicated a remarkably evolved, deeply thought and surely uniquely musical and personal vision of this powerful Chopin sonata. All this completed on the evocative, time-traveled sound world of the 1858 Erard.

Improvisation on a theme Prelude in E minor, Op. 28 No. 4

Fryderyk Chopin / Aleksandra Świgut

I found this to be a particularly charming and winningly musical improvisation on a well-known Chopin Prelude. Young pianists should be encouraged far more to improvise. All the great pianist-composers and many less elevated talents improvised as a matter of course. Chopin was famed for his genius for improvisation.

A highly recommended, brilliant purchase to uplift the spirit in our benighted times

National Chopin Institute Shop

CD No: NIFCCD 095

https://sklep.nifc.pl/en/produkt/77399-aleksandra-swigut-chopin

Thank you so much for this remarkable and thorough review of Aleksandra's recording. I too have been following her, in particular since her apperance in the first International Chopin Competition on Period Instruments. I hope many will follow your advice and seek out this performance. For those who stream, it is available on Apple Music and Tidal, but not on Qobuz, which for some strange reason, does not carry the Chopin Institute's wonderful recordings.

ReplyDelete