Felix Yaniewicz - Music and Migration in Georgian Edinburgh - A remarkable rediscovery. Review of a remarkable CD. Review of the Concert Friday 16th February 2024, Warsaw Philharmonic

I traveled to Edinburgh towards the end of June 2022 and among the many adventures and museums visited, I managed to be there for the opening of a remarkable exhibition at the Georgian House. I live in Warsaw in Poland, move in musical circles there, but had never encountered this artist. I was astounded at the discovery.

[Throughout this post I have adopted the anglicized spelling of his name that he favoured in Edinburgh beginning with 'Y' (Yaniewicz) rather than the Polish 'J' (Janiewicz)]

I met and had a long instructive conversation with the exhibition curator Josie Dixon who assembled and wrote an excellent article on Felix Yaniewicz, her ancestor and a Polish virtuoso violinist, composer and businessman who was the catalyzing founding force behind the present, world-renowned, Edinburgh Festival. But this was in 1815 !

Review of the Warsaw concert at the Warsaw Philharmonic, Friday 16th February 2024 at 19.30

Wrocław Baroque Orchestra NFM

Andrzej Kosendiak conductor

Bartłomiej Nizioł Violin (1727 Guaneri del Gesú with gut strings)

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Overture to the opera L'isola disabitata (The uninhabited island) Hob. XXVIII:9 (1789) was the tenth opera Haydn composed with a libretto by the famed Metastasio. It is a famous example, in a way a miniature symphony, of a dramatic Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) style. This was a proto-Romantic movement in German literature and music that occurred between the late 1760s and early 1780s. Individual subjectivity and, in particular, extremes of emotion were given free expression in reaction to the perceived constraints of rationalism imposed by the Enlightenment and associated aesthetic movements.

Wrocław Baroque Orchestra is operating at the National Forum of Music. It is a dynamically developing ensemble that has performed with such renowned conductors as Philippe Herreweghe, Giovanni Antonini, Andreas Spering, Hans-Christoph Rademann and Rubén Dubrovsky. This work, conducted by their founder and director Andrzej Kosendiak, was a fine performance of this explosive work.

Feliks Yaniewicz (1762-1848)

[See Feature below]

Violin Concerto No. 4 in A major (c.1790)

Yaniewicz tends to use the orchestra in the enthusiastic Moderato opening movement as a platform for spectacular, virtuosic display on the violin which Nizioł commanded like tiger on its prey. It is not surprising that Paganini when he heard Yaniewicz perform was quite overwhelmed and termed him 'a master'. The Adagio was full of melodic charm and affectation which enabled the aesthetic beauties of the historic Guaneri instrument to glow.

The subjective nature was emphasized with solo passages on the violin of greater length than is conventional. The final Rondo: Allegretto had an infectious , catchy rhythm of inner joy and entertaining fun which required a highly virtuosic in technique. Nizioł was more than up to this task however I felt at times he had difficulty with intonation.

Feliks Yaniewicz

[See feature below]

5th Violin Concerto in E minor (c.1800)

This concerto is the finest for me of his set of five. The opening Largo is dark and a touch forbidding. The following Allegro. Moderato is highly emotional, dramatic and subjective Sturm und Drang melody and put me in mind of the Mozart D minor piano concerto in its intense emotionalism. This or even the premonitory energy within Verdi overture to La Forza de Destino. Mozart admired Yaniewicz greatly. In fact, Mozart’s 19th-century biographer Otto Jahn speculates that his lost Andante in A major K470 written at this time may have been composed for Yaniewicz.

Michael Kelly, a famous tenor, wrote that while in Vienna he was privileged to hear one of the foremost violinists in the world: ‘...a very young man, in the service of the King of Poland, he touched the instrument with thrilling effect, and was an excellent leader of an orchestra. His concertos always finished with some pretty Polonaise air; his variations were truly beautiful.’

The composition certainly sets the individual soaring virtuoso violin part as a superb display piece against the orchestra. The long, polyphonic cadenza was dazzling and absolutely sensational, rather like a prized piece of decorative Sevres porcelain displayed in a solitary cabinet in a Parisian museum.

The Adagio was lyrical and affecting as pastoral melody of love gliding above pizzicato orchestral violins. The glorious tone of the Guaneri was again displayed in panoramic sound. Can one have a cadenza to a second movement Adagio ? An extraordinarily long period by the soloist that led magically attaca (no pause) into the spirited and exuberant Rondo. Allegretto. This conclusion was rich in unmistakeable folkloric, Jewish dancing elements and physical joy. There was a beautiful balance maintained here between the virtuosic violin soloist Nizioł and minimalist orchestral writing and accompaniment under Kosendiak. I felt at times I could have been in Kazimierz in Kraków during a late evening in a tavern. The accelerando conclusion was exciting and uplifting in gaiety.

I cannot imagine why this concerto has not been absorbed into the conventional repertoire and take pleasure in hearing sheer tuneful, ornamented virtuosity. We do not always need to inhabit the 'dark night of the soul' in a concert hall. Here we had a balance of temperament, the unalloyed ideal of Sturm und Drang.

As an encore Nizioł gave a superbly executed, high virtuoso and spirited performance of the Paganini Capriccio No.9 in E major 'The Hunt'.

Joseph Haydn

Symphony in G minor "The Hen" Hob I:83

Joseph Haydn’s so-called 'Paris' Symphonies were composed in 1785 and 1786 for the masonic lodge 'Société Olympique' in Paris, which ran a large orchestra and organised regular concerts. These six works are notable for their artful motivic work and playful wit. Haydn here pays tribute both to the discerning taste of the Paris audience and to the excellent abilities of the musicians in the orchestra. These symphonies rapidly became famous and popular throughout Europe, thanks to editions published variously in Paris, Vienna and London.

The Symphony no. 83 in G minor is the only Paris Symphony in a minor key. Its nickname 'La Poule' ('The hen') was not coined by Haydn. But it’s almost impossible not to be reminded of the bird when listening to the oboe’s 'cluckings' in the second theme of the first movement. (Henle)

This was a fine and amusing performance of a Haydn symphony that followed the Strum und Drang movement.

The present Polish musical renaissance and resuscitation of fine compositions of forgotten masters continues apace. A musical Aladdin's Cave of gems has been courageously thrust open!

The 'Iron Curtain' was as much a cultural barrier as a military and political one. The internet knows no such barriers to archival cultural material in our period. We live in an era of extraordinary freedom, ease and variety of access. This in addition to the possibility of limitless repetition of works through the extraordinary advances in recording.

The remarkable recent recording of two violin concertos by Duranowski and Yaniewicz (and a fine adolescent Mozart symphony) from the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute, presents two beacons of past Polish musical excellence. These composers were once renowned internationally in their time as composers and instrumentalists of genius. However, as the decades passed they inexorably fell from their former grace into fungous obscurity, except among academics and musicologists.

|

| Chouchane Siranossian |

The eminent violinist Chouchane Siranossian is of Armenian descent but born in France. She performs on a Baroque violin (made by one of the finest Italian luthiers in history, Giovanni Battista Guadagnini [1711 - 1786]). The ﹛oh!﹜Orchestra, who specialise in historically informed performance, is conducted by their gifted artistic director, Martyna Pastuszka.

August Fryderyk Duranowski (1770-1834) was born in Warsaw with a similar parental background to Chopin - a Polish mother and French immigrant father. This precocious boy was already in Paris at age 17 studying violin with Giovanni Battista Viotti. He was quite the adventurer joining Napoleon's army in 1796, was imprisoned in Milan but with some character resumed his concert engagements at Napoleon's court. He traveled widely internationally, possibly playing even in Russia. One must remember that travel at that time was slow and hazardous.

He was one of the most famous violinists of the day with a stunning technique, rich tone and glittering trills. His accomplishment was such that Paganini himself was overcome with enthusiasm for his talent. The virtuosic Duranowski concerto performed here was dedicated to the Polish aristocrat Madame la Princesse Maréchal Lubomirska.

|

| August Fryderyk Duranowski (1770-1834) |

The opening Allegro spiritoso movement is full of untroubled sprightly energy, panache and ardent charm. We are instantly transported to another possibly more civilized age by the effortless virtuosity and graceful musical phrasing of Siranossian on the gloriously toned Guadagnini. The violin comes much to the fore in a ravishing display suspended like a swooping lark over the relatively small orchestra. The Adagio is reflective and refined but scarcely emotionally moving in thought. The Rondo is delightfully virtuosic with a foot-tapping, flowing and highly entertaining melody. It is a splendid vehicle for Siranossian to display the seductive nature of her attractive command of this historic instrument.

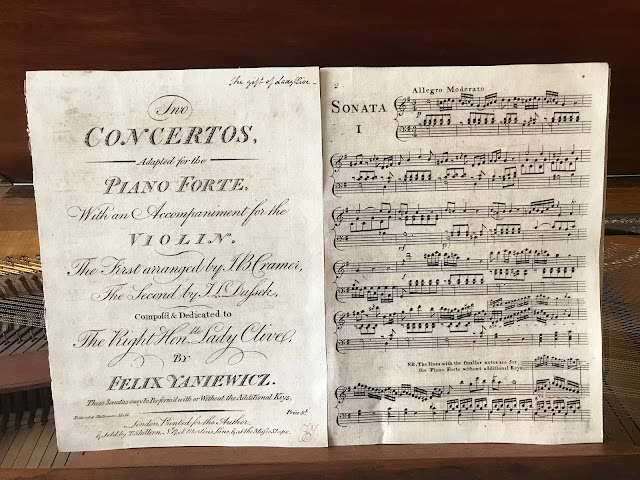

The background to Feliks Yaniewicz (1762-1848) and my abiding interest in him is presented in great detail below. Do read if you can spare the time! The Third Violin Concerto in A major of c.1790 was written in Paris (of five violin concerti he wrote, as well as much chamber music). In the opening Allegro the violin leaps into the foreground of the musical picture with élan and unstoppable forward virtuosic momentum. Siranossian plays the winning melody with immense authority and copes effortlessly with the glittering figuration, leaps, double stops in thirds, sixths and octaves, triplets and marked up articulation.

In the Adagio we have a demonstration of the celebrated Viotti cantabile which Siranossian exploits poignantly in song and expressive sensibility using the rich timbre of the Guadagnini. Yaniewicz was lauded for the intense quality of feeling his legato playing aroused in the audience. The concluding Rondo puts one in mind of the dancing pleasures of the Assembly Rooms in Bath or the Pleasure Gardens of Vauxhall and Ranelagh. It possesses such an infectious and catchy yet refined melody that only makes a demand on our sense of taking extreme pleasure in delightful, highly virtuosic violin music. Siranossian is faultless and exuberant in this tumult of violin high jinks ! Quite wonderful !

The last work on this CD is the rarely performed early Symphony in A major K.114 by Mozart. The composer, between the ages of 14 and 17, traveled a great deal guided by his father. He was absorbing like a sponge the aesthetic musical delights of Italy, an unsurpassed influence on the European musicians of the day. Between his second and third trips to la bella Italia (15th December 1771 to 24th October 1772) he composed no less than eight symphonies, the first being this one in A major K 114.

That this composition emerged from the mind and sensibility of a 15 year old boy is scarcely to be credited. The ﹛oh!﹜Orchestra conducted by Martyna Pastuszka were suitably energetic and expressed the contained but scarcely repressed adolescent spirit and joy in life most convincingly. The Allegro moderato opens like a wonderful spring bloom on the compagna. I particularly loved the period inadmissible concertante fortepiano part woven throughout the symphony in decorative addition and harmonic support. This addition to the musical fabric was played tastefully, musically and charmingly by Anna Firlus on a copy of a fortepiano by the German builder Johann Andreas Stein (1728-1792). The musicologist Marcin Majchrowski writes in his excellent CD notes for this beautifully produced and illustrated disc : This is a musical portrayal of Eden, with its rampant luxuriance !

The lyrical Adagio puts one in mind of a musical Arcadia. Yet shadows cross the sun in the contrasting Menuetto until the Molto allegro finale erupts under the baton of Pastuszka with almost overpowering energy, muscularity and sheer joy in life itself. I was reminded of Joseph Conrad's exclamation: "Ah youth ! The joy of it !" Jens Peter Larsen, the Danish musicologist and Haydn scholar describes the symphony as 'one of [Mozart's] most inspired symphonies of that period.'

So here we have a yet another inspiring CD from the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute recorded to balanced perfection once again by Lech Dudzik and Julita Emanuiłow.

Felix Yaniewicz

Music and Migration in Georgian Edinburgh

Written by Josie Dixon, Curator of Music and Migration in Georgian Edinburgh

|

| Felix Yaniewicz (1823-1848) | Image courtesy of The Friends of Felix Yaniewicz |

Visitors exploring Edinburgh’s New Town may find themselves walking past 84 Great King St, where an inscription on a cornerstone by the door records, ‘Felix Yaniewicz, Polish composer and musician, co-founder of First Edinburgh Music Festival, lived and died here 1823–1848’.

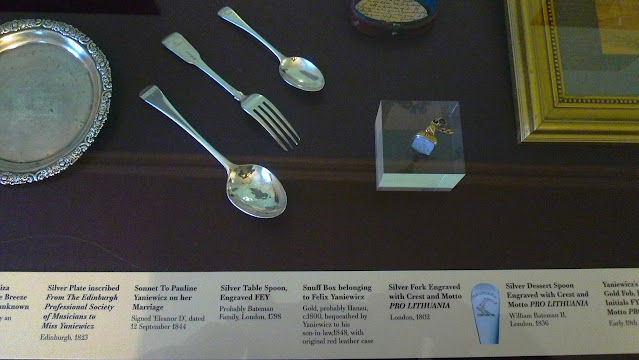

The story behind this inscription has remained untold until now, but between 25 June–22 October 2022 you could see an exhibition at the Georgian House on Yaniewicz’s remarkable life celebrating his musical legacy in Scotland. It showcased a unique collection of musical instruments, portraits, silver and gold heirlooms, letters and manuscripts, offering a fascinating insight into the career of this charismatic performer, composer and impresario who left a lasting mark on Scottish musical culture. The associated talks and events highlighted the cosmopolitan roots of Scottish heritage, and the vital role of migration in shaping the cultural life of Georgian Edinburgh.

|

| 84 King Street, Edinburgh where Felix Yaniewicz lived (Image Michael Moran) |

|

| Felix Yaniewicz Commemorative Plaque at 84 King Street, Edinburgh (Image Michael Moran) |

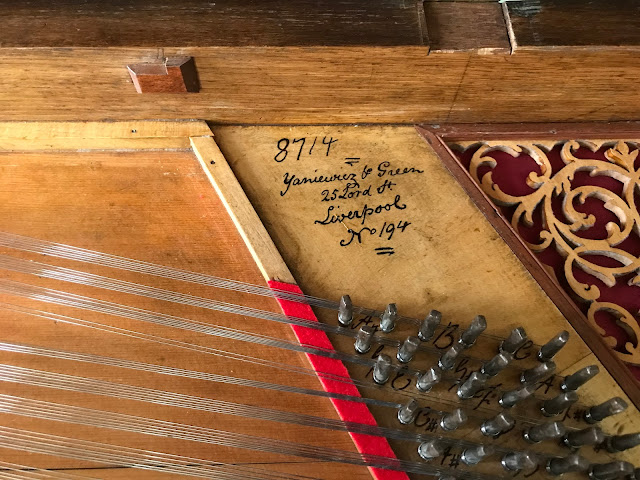

The project came about with the chance discovery of a beautiful square piano, dated around 1810. It was found in dilapidated condition in a private house in Snowdonia by Douglas Hollick, an expert on early keyboard instruments, who recognized its historical significance and potential for restoration. Above the keyboard, a gilded cartouche with painted flowers and musical instruments bears the label ‘Yaniewicz & Green’, with addresses in fashionable areas of London and Liverpool.

|

| Yaniewicz & Green Square Piano in the Drawing Room of the Georgian House, Edinburgh (Image Michael Moran) |

|

| Inscription inside the piano written by Yaniewicz (Image Michael Moran) |

Watch now: the Yaniewicz & Green square piano

Inside the piano, the signature in Indian ink has been matched with the marriage certificate of Felix Yaniewicz, a Polish-Lithuanian violin virtuoso and composer, who fled the continent during the French Revolution and settled in Britain.

Some years later, newly restored as a working instrument, the piano was put up for sale, and by chance the advertisement was spotted by one of Yaniewicz’s surviving descendants. ‘It was a thrilling moment,’ recalls Josie Dixon. ‘Yaniewicz was my great-great-great-great-grandfather. When I was growing up, his portrait hung in my grandmother’s cottage: a handsome, enigmatic presence with more than a touch of Mr Darcy.’

Quote:

“At the time, I knew little of his life, but discovering this instrument with a very direct connection to my ancestor inspired me to find out more about his story.”

Josie Dixon

Exhibition curator and descendant of Felix Yaniewicz

Josie hatched a plan for a crowdfunding campaign, to save the piano from falling into private hands and to bring it to Edinburgh to mark Yaniewicz’s musical legacy in Scotland. The project became a collaboration with the Scottish Polish Cultural Association, and funds were raised from all over Britain, Poland, Germany, Norway, France, Italy, Switzerland and the USA. Donors included the composer Roxana Panufnik, marking over 200 years of Polish musical heritage in Britain.

The final donation was made by an Edinburgh doctor in memory of her father, Stanislaw Zawerbny, a Polish veteran, with funds collected at his 100th birthday, and afterwards at his funeral – a poignant indication of how this project had been taken to heart in the Scottish Polish community. The Polish Ex-Combatants’ Association offered to house the piano at their former club house on Drummond Place, just around the corner from Yaniewicz’s residence on Great King Street.

On 10 November 2021, the piano began its journey north from the restorer’s workshop in Lincolnshire to its new home in Edinburgh. Its arrival was celebrated with two inaugural recitals by Steven Devine and Pawel Siwczak, setting Yaniewicz’s music in the context of contemporary composers from across Europe, and from his native Poland.

|

| The Drawing Room of the Georgian House, Edinburgh, where the piano is displayed |

This summer of 2022, the piano will make a shorter journey for the exhibition at the Georgian House, where it will be on display alongside family heirlooms which were passed down the generations among Yaniewicz’s descendants and have never been seen in public before. These musical instruments, portraits, personal possessions and letters have a remarkable story to tell, about the life of a celebrated musician who changed the course of Scottish musical history.

He was born Feliks Yaniewicz in 1762 in Vilnius (then part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth), and rose to prominence as a performer in the Polish Royal chapel. King Stanislaus August Poniatowski, a great patron of the arts, paid for him to travel to Vienna, where he encountered Haydn and Mozart.

|

| ‘Janievitz’ from Professori Celebri Del Suono | AKG images / Berlin Sammlung Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte |

Mozart’s 19th-century biographer Otto Jahn speculates that his lost Andante in A major K470 written at this time may have been composed for Yaniewicz. Michael Kelly, a famous tenor, wrote that while in Vienna he was privileged to hear one of the foremost violinists in the world: ‘...a very young man, in the service of the King of Poland, he touched the instrument with thrilling effect, and was an excellent leader of an orchestra. His concertos always finished with some pretty Polonaise air; his variations were truly beautiful.’

Yaniewicz travelled to Italy and then to Paris, where he made his concert debut in 1787, and found a patron in the Duke of Orléans. But these were turbulent times, and a few years later, with France in revolution and his native land in political meltdown, he fled to Britain as a refugee and joined a community of musical emigrés in London.

There he played in Salomon’s orchestra, conducted by Haydn, performing solo concertos at the Hanover Square Rooms in 1792. In Bath later that year, he was hailed as ‘the celebrated Mr Yaniewicz’ – now spelling his name with the anglicized Y which he adopted for the rest of his life, perhaps signalling his desire to assimilate and a decision to settle in Britain.

The lost Stradivarius

Yaniewicz was effectively what one might term a refugee musician in Britain but he had managed to salvage his precious violins. He owned a beautiful inlaid double violin case (on display in the exhibition). The architect Charles Harrison Townsend, his grandson, wrote a family inventory of effects in 1925 among which is described the destiny of two Yaniewicz violins.

'His Strad he sold for £60, about 1845 (£8,100 in 2022) See his own letter on the subject ... This violin was (so says the violin-expert A. Hill of Bond Street - who knows it well) a celebrated instrument and is now in the possession of a New York collector, well known to Hill. His Amati was raffled for, and produced 40 guineas!'

The present whereabouts of the Stradivarius and Amati, the sounds of which had seduced audiences in Britain, remain a mystery.

|

| The inlaid double violin case that may have contained the Stradivarius and Amati instruments owned by Yaniewicz. A silver table bell to the right (Image Michael Moran) |

He toured the country as a charismatic performer and energetic impresario, playing concerts in fashionable cities, including Dublin where his concert series in 1799 was billed as ‘Mr Yaniewicz’s Nights’. In London he was a founder member of the Philharmonic Society (marking a pivotal moment in the transition from the patronage system to musical meritocracy) and mounted the first British performance of Beethoven’s oratorio, Christ on the Mount of Olives.

|

Framed drawing of Eliza Yaniewicz (nee Breeze) by an unknown artist, no date |

In 1799 Yaniewicz moved to Liverpool and married an Englishwoman, Eliza Breeze. Cutting a dash on the social scene, he caught the attention of The Monthly Mirror: ‘...he combines the utile with the dolce. He is married at Liverpool; leads the concerts; and is (à la Liverpool) a man of business.’

By the end of 1800 he was also a family man, with a daughter Felicia (the first of three children to survive beyond infancy), so a steady income was called for. A business dealing in musical instruments marked a new strand to his portfolio. In 1801 he opened a warehouse in Lord Street, one of two premises for this enterprise, in partnerships with John Green and a London pianoforte maker, Thomas Loud.

|

| The address label on the 1810 square piano for ‘Yaniewicz & Green’ (Image Michael Moran) |

The Yaniewicz & Green square piano bears the hallmarks of the London workshop of Clementi, the foremost piano manufacturer of the day. A fellow émigré and composer, Clementi had met Yaniewicz in the 1790s in London. They appear together around the same dining table in the diary of the political philosopher William Godwin, who records that quartets were played after dinner.

By the early 1800s they were in business together. Clementi’s firm made the instruments, while Yaniewicz and partners would have ordered customised designs for their fashionable clients in London and Liverpool, using his celebrity status to enhance the brand of their retail operation. Another survival of their collaboration is the beautiful Apollo lyre guitar, now in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter.

An Apollo Lyre Guitar, made by Yaniewicz and Company in Liverpool c.1800. On loan to the exhibition at the Georgian House from The Royal Albert Museum in Exeter (Image Michael Moran) |

Yaniewicz, however, was moving north. He had first given touring concerts in Edinburgh in 1804, and was immediately a sensation. Three subscription concerts at Corri’s Rooms were followed by a benefit concert, at which his performance was hailed as ‘...a perfect masterpiece of the art. In fire, spirit, elegance and finish, Mr Yaniewicz’s violin concerto cannot be excelled by any performance in Europe.’

So perhaps it was not surprising that it was in Edinburgh that he undertook his boldest initiative, as co-founder of the first music festival in October 1815. An article by Karen Macaulay has shown that the idea originated with Angelica Catalani – the operatic superstar of the day, with whom Yaniewicz had a long collaboration on the concert platform, from as early as 1807 until her retirement in 1824.*

Read more: A lady’s diary of the first Edinburgh Musical Festival

In 1814 Mme Catalani set out in an advertisement in the Caledonian Mercury bold plans for an event on which she failed to deliver, but Yaniewicz and his colleagues brought off the 1815 festival in style. Before the year was out, he and Eliza moved to Scotland and made Edinburgh their home for good.

|

| Angelica Catalani (1780-1849) by Rolinda Sharples (1793-1838) |

* Michael Moran adds that on November 21, 1819, Angelica Catalani appeared in Warsaw. She stayed at the elegant home of one of her relatives, Konstanty Wolicki. The ten year old Chopin heard La Catalani sing, perhaps igniting the fire of his passion for opera. Naturally, she requested he play. She was so enchanted by his performance she presented him with a gold pocket watch, now a precious inscribed relic in the Chopin Museum in Warsaw.

|

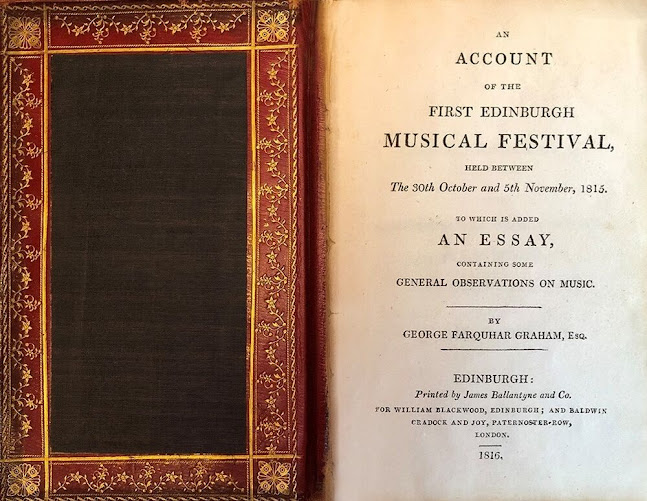

| Title page from George Farquhar Graham’s An Account of the First Edinburgh Music Festival (Edinburgh, 1816) Image courtesy of The Friends of Felix Yaniewicz |

Among the memorabilia on display will be a first edition of An Account of the First Edinburgh Music Festival 1815 by one of its secretaries, George Farquhar Graham. The volume is inscribed on the flyleaf ‘To Mrs Yaniewicz, as a small mark of the author’s esteem and friendship.’ It contains a long list of the festival’s aristocratic patrons, the programmes for every concert, and Farquhar Graham’s lengthy reviews of the performances, together with ‘an essay containing some general observations on music’.

Farquhar Graham’s account gives an evocative insight into the atmosphere and excitement surrounding the festival, captured in this description of the build-up to the first concert in Parliament Hall:

‘...the large and beautiful orchestra filled with eminent performers; the multitude of well-dressed persons occupying the gallery… the novelty of the occasion; the spaciousness of the place whose high walls, and massive sober ornaments were illuminated by the bright beams of the morning sun; together with the expectations of the serious and magnificent entertainment which was about to commence powerfully contributed to produce in every one a state of mental elevation and delight, rarely to be experienced.’

Grand concerts in Parliament Hall combined major oratorios – Haydn’s Creation and Handel’s Messiah – with operatic arias, Haydn symphonies and Yaniewicz’s violin concertos.

|

| (Image Michael Moran) |

Evening concerts were in Corri’s Rooms, a private concert venue established by the Italian Natale Corri (brother of Domenico Corri who had moved to Edinburgh in 1771 to direct the concerts of the Edinburgh Music Society in St Cecilia’s Hall). These concerts may have been smaller in scale, but were scarcely less ambitious, featuring symphonies by Mozart and Beethoven as well as another of Yaniewicz’s violin concertos. This was a formidable amount of music for the same group of performers to present in the space of a few days, and Yaniewicz led the orchestra throughout.

Farquhar Graham’s introduction presents the festival as a turning point in Scottish musical taste, moving away from national folk culture and towards the classical, continental tradition that Yaniewicz represented, trailing clouds of musical glory from his encounters with Haydn and Mozart in Vienna.

At the end of his preface, Farquhar Graham dared to speculate about the legacy of this foundational event in the nation’s musical culture, in a moment that seems to court posterity: ‘...it has excited much temporary interest – and it may be followed by important consequences, at a time when the hand that now attempts to describe its immediate effects, and the hearts of all who participated in its pleasures, are mouldered into dust.’

If the founders of the Edinburgh International Festival, in the aftermath of the Second World War, can be seen as the successors of their counterparts in 1815, Farquhar Graham’s prediction has been more richly fulfilled than he could ever have imagined.

More immediately, the 1815 festival gave rise to the Edinburgh Institution for the encouragement of Sacred Music, established on 28 December 1816. The report on their annual general meeting, chaired by the Lord Provost, echoes Farquhar Graham, deploring Scotland’s ‘national deficiency’ in the realm of sacred music, seen as a touchstone of civilisation. The Scottish attachment to folk music was held responsible for ‘a certain prejudice which still exists against any departure from the naked simplicity of our earliest melodies. The native musical taste of Scotland can hardly be said to relish the charms of harmony’. The report hails the previous year’s events as pivotal in Scotland’s emergence from this backward state:

‘It was the musical festival of 1815, which gave a new turn in this quarter, to the general feeling on the subject of sacred music: and […] laid the foundation for an improved taste in this country. Those splendid performances, in which variety, richness, and elegance, were so remarkably combined, filled the audience with emotions, which probably had never before been excited in Scotland by the power of music.’

It goes on to record the Institution’s concerts in 1816–17, in which ‘the effect […] was increased by the admirable talents of Mr Yaniewicz, who on this occasion obligingly consented to lead the band, and has ever since given his powerful assistance, both at the rehearsals and public performances.’ It ends by predicting that the establishment of this new institution ‘will be justly regarded by future times as a new era in the musical history of Scotland.’

The year after the 1815 festival, Corri retired as Edinburgh’s chief concert promoter and Yaniewicz was the obvious choice to succeed him. He instituted a series of ‘morning concerts’ of chamber music (actually at 2pm), ‘attended by a numerous and fashionable audience’. Later, in the 1820s, these Monday concerts were moved to Saturdays, suggesting a shift in his clientele from the leisured upper echelons of Edinburgh society to the professional classes.

|

Yaniewicz’s gravestone can be found in Warriston cemetery in Edinburgh |

1829 saw Yaniewicz’s farewell concert in Edinburgh, after which he began to disappear from public view. But it is tempting to wonder whether he crossed paths with another Felix who visited the city that year, on his way to a tour of the Highlands and the Hebrides. Mendelssohn stayed in the city for four days in July 1829, climbing Arthur’s Seat and finding the first inspiration for his Scottish Symphony in the ruined Abbey of Holyrood Palace. He stayed in Albany Street, a 10-minute walk from Yaniewicz’s residence, and it is not difficult to imagine that Yaniewicz would have been a guest at one of the soirées organised for Mendelssohn’s visit.

He lived at Great King Street for almost two more decades, though sadly not quite long enough to encounter his compatriot Chopin, who visited Scotland in the autumn of 1848. Only a few months after, Yaniewicz died in May of that year. Until the very end of his life he embraced nostalgia for his Lithuanian birthplace, Vilnius, and the country's national identity, even having his cutlery and gold seal fob engraved with the Crest and Motto PRO LITHUANIA.

Yaniewicz is buried in Warriston Cemetery, where his gravestone commemorates ‘a most eminent and accomplished musician […] honoured, loved and regretted’. A fitting obituary can be found in Noctes Ambrosianae, published in Blackwoods Magazine in 1826:

‘Let Yaniewicz, and Finlay Dun and Murray, play solos of various kinds – divine airs of the great old masters, illustrious or obscure – airs that may lap the soul in Elysium. Let them also, at times, join their eloquent violins, and harmoniously discourse in a celestial colloquy: they are men of taste, feeling, and genius.’

Comments

Post a Comment