Arthur Rubinstein and the Ache of Love. His last concert in Poland recorded on the occasion of the 60th Anniversary of the Łódź Philharmonic, 30th May 1975 - A rare Rubinstein recording

A number of memorable moments are associated in my mind with the genius of Artur Rubinstein. One was some time after I gave a short recital of Chopin at the age of 8 in the Town Hall in Melbourne. At that time I was vainly cultivating the illusory dream of becoming a concert pianist. I first heard the unforgettable Rubinstein himself play live in the Sydney Town Hall when I was about 15. Years later I took his complete Chopin vinyl recordings and my C. Bechstein piano to a remote Pacific island where I had decided to live and practice.

Later Rubinstein performances in London accompanied the slow dissolving of my artistic dreams in the grey fog of reality and recognition of the limitations of talent. Artur Rubinstein died in Geneva on 20 December 1982 at the age of 95. However, there was one unearthly Rubinstein 'recital' at the Royal Festival Hall not long after his death. Yes, after his death.

It is not generally known that before the exponential development of recording quality - Edison rolls, 78 rpm shellac discs through to stereo vinyl LPs, cassette tapes to the present high definition CDs and digital downloads - there was a remarkable system of recording on piano rolls. These were not simple pianolas familiar to our entertaining grandparents. These recording and reproducing pianos were highly complex pneumatic devices with bellows, tubes and pumps built into concert grand pianos. These devices could record and reproduce all the delicate phrasing, dynamics, articulation and interpretative gestures of the performing artist or composer. Many different systems evolved and were assessed - '... the Ampico appeals to our sense of excitement, the Duo-Art fascinates our intellect, but the Welte-Mignon touches our soul.'

They developed in time into superb recording devices and many distinguished artists and composers recorded for them. The young Artur Rubinstein recorded Duo-Art Piano rolls from 1919 - 1924. Between 1913 and 1925 pianists such as Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Josef Hofmann, Percy Grainger, Teresa Carreño, Aurelio Giorni, Robert Armbruster and Vladimir Horowitz all recorded for Duo-Art. Their rolls are a legacy of 19th-century and early 20th-century aesthetic and musical practice.

The concert at the Royal Festival Hall that I attended was a memorial Artur Rubinstein 'recital' presented after his death. It was 'performed' on a Steinway Duo-Art reproducing piano.

The open instrument and physically vacant stool stood alone, isolate yet powerfully present on the vast stage before a silent audience. Memories of the artist lay softly over us like the dusty wings of a night moth. A gentle and delicate-voiced introduction by a presenter before Rubinstein began to play. He had again come to us suspended on clouds of song to perform from beyond the grave.

The animated yet deserted keys were ghostly, an apparition moving as if animated by a spectre, an unseen metaphysical force. This profound experience in no way resembled listening to a modern recording. In a concert hall that he had once performed in, Rubinstein once more created an indelible, indescribably moving emotional effect.

Engaging once again the massive physical presence and rich tone of a Steinway, he articulated Chopin with his unique musical penetration and artistry. We heard the Polonaise in F sharp minor Op.44, a number of Preludes from Op.28 including the existentially disturbing No.24 in D minor and other works I cannot quite remember. The transported audience left the hall in absolute silence without the slightest whisper of applause. Certainly this was a unique musical moment of immense significance and power.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ul79ifdeBKk

(Rubinstein's recording of the Chopin F-sharp minor Polonaise for the Duo-Art system, issued in February 1922, roll 6505. Played on a Weber model 12 grand)

Another remarkable recent 'Rubinstein moment' unexpectedly occurred for me in Warsaw with the current release by the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute of a live recording of Rubinstein's last concert in Poland at his birthplace of Łodź on 30 May 1975. This priceless gem is one of greatest accounts of the Chopin F minor concerto I have ever heard. The concert was recorded on the occasion of the 60th Anniversary of the Łódź Philharmonic.

.png) |

| NIFCCD 155-156 |

It consists of three works on two CDs. In print the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute warmly thanked Ewa, Alina and John Rubinstein for agreeing to the release of these rare, late recordings. This finely packaged CD contains touching notes on the event, a précis of Rubinstein's career by the Artistic Director of the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute Stanisław Leszczyński as well as a number of affecting stills from a film made on this historic occasion. Rubinstein was 88 at the time of this concert, which in itself is a variety of miracle.

|

| Arthur Rubinstein's signature on a C. Bechstein grand piano in the Music Gallery of the Rubinstein Museum in Łódź. Played by him and also by Witold Małcużyński |

Fryderyk

Chopin (1810-1849)

Piano Concerto in F minor, Op.21

The

Łódź Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Henryk Czyż

Fryderyk Chopin once observed on his Concerto in F minor Op.21

'There are people with whom studying this is impossible for me'

One must remember, despite the opus number, that this was the first piano concerto Chopin wrote. It follows the Mozart model and was directly influenced by the style brillant of Hummel, Kalkbrenner, Moscheles and Ries. Schumann wrote of it: 'Of the second concerto, which we can all together barely reach, we can only kiss the edge of his royal garment.'

This inspirational remark on the gestation of the concerto is rightly famous:

‘As I already have, perhaps unfortunately, my ideal, whom I faithfully serve, without having spoken to her for half a year already, of whom I dream, in remembrance of whom was created the adagio of my concerto’

(Chopin to his friend Tytus Woyciechowski, 3 October 1829).

The work itself was written 1829-30. As we all know by now, this concerto was inspired by Chopin’s infatuation, or was it youthful love, for the soprano Konstancja Gładkowska. Strangely perhaps, it was published a few years later with a dedication to Delfina Potocka.

Its premiere took place on March 17, 1830, at the National Theatre in Warsaw. An anonymous reviewer (probably Wojciech Grzymała) in Kurier Polski summed up the mastery of the work:

'In addition to originality, beautiful singing, great and bold passages applied to the nature of the instrument, decorated in vivid colours of feeling and fire, finally, the combination of all this into one whole, constitute the main feature of his composition.'

The extraordinary work, practically without precedent, inevitably entered not only Polish but also European piano literature.

Rubinstein brings a long lifetime of intimate musical familiarity with Chopin to his performance of this work. In a word, it is an affectingly superb account. The Concerto in F minor op. 21 is the fruit of Chopin's youthful compositional spontaneity and a degree of innocence. Written following his success in Vienna, it gives the impression of a matter of extraordinary coherence of mood and musical narrative.

The opening Allegro movement is marked Maestoso and Rubinstein adopted a majestic tempo which followed a fragile line between balanced, Mozartian classical, style brillante delights and relatively serious yet not tragic theme. The seductive, glowing Rubinstein tone and legato linking of musical narrative is quite wonderful and movingly illuminating.

The essence of the Concerto in

F minor, however, is its central section and the aching, lyric melody of

illusioned, yearning love. The poetry has

refinement of feeling and emotion that brings to the Larghetto an incomparable atmosphere. He plumbs the depths of his own romantic heart and soul and takes

us with him gifted as companions. The effect is almost unearthly and poetic. Many

feel it to be the most beautiful and erotic love song ever written. Listening

to Rubinstein's account, it is impossible to demur with this generalisation. Chopin's compositions seduces the listener with idyllic, nocturnal atmosphere of dream, soothing

him with poignant cantilena fiorituras and swaying rhythms. Rubinstein

reveals submerged energetic passions that escape lyrical restraint with a tremolando

background bordering on ecstasy. We then

return to the dream as is so often the case after Chopinesque agitation at the

intrusion of grey reality but hinting at the slumbering joys of inaccessible

reverie. The Larghetto was enthusiastically received already

during the first performance and remains, certainly with Rubinstein, the most touching

pages of European romanticism. Liszt saw in it 'ideal perfection'.

In the third Allegro vivace movement , Rubinstein is rejuvenated with exuberant youth, a manifestation of magic dust unexpected in advanced age. Playful without indulgent sentiment, willfully embracing the energy of life coursing through his being. La Chasse (call to the hunt) on the French horn was perfect in style and intonation ! Minor solecisms by Rubinstein only add to the miracle of this performance suffused by this extraordinary, even miraculous, return to the city of his birth.

.jpg) |

| Bombardment of Vienna by the French Army 11th May 1809 Baron Louis Albert Bacler d'Albe |

Ludwig

van Beethoven (1776-1827)

Piano

Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 73

Polonaise in A flat major, Op.53 (encore)

The

Łódź Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Henryk Czyż

Beethoven dedicated the ‘Emperor’ Concerto to Archduke Rudolph, a fine pianist, and the composer’s student as well as friend and patron, who was the soloist for the first private performance on January 13, 1811, at Prince Lobkowitz’s palace in Vienna. The first public performance of the ‘Emperor’ Concerto was on November 28, 1811, at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, with Friedrich Schneider as soloist. The reaction was galvanic. The Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung reported 'It is, without doubt, one of the most original, imaginative and effective, but also one of the most difficult of all existing concertos.' Carl Czerny, a student of Beethoven’s and later the teacher of Liszt, gave its official Viennese premiere early in 1812. Who gifted the title of 'Emperor' is rather uncertain.

Beethoven had begun composing his ‘Emperor’ Concerto in 1809, while Vienna was under invasion from Napoleon’s forces for the second time. Adam Zamoyski writes in his book Napoleon: The Man Behind the Myth that Achille de Broglie, a member of the Council of State, considered that all the generals longed for peace 'cursing their master' and looking to the future with 'great apprehension'. General Vandamme on one occasion burst out 'He's a coward, a cheat, a liar.' Admiral Decrés felt 'The Emperor is mad, completely mad...' Napoleon enjoyed delightful evenings at Schönbrunn and even invited Marie Walewska to join him.

Beethoven embraced a different reality. He was living in a top-floor apartment owned by Baron Pasqualati beside the ramparts. He was forced to shelter in the basement of his brother Kasper’s house, pressing pillows to his ears to protect what remained of his hearing. He was unable to perform this concerto because he could scarcely hear the orchestra. 'The whole course of events has affected my body and soul,' he wrote. 'What a disturbing, wild life around me; nothing but drums, cannons, men, misery of all sorts.' The war was ruinous for Austria and many aristocrats fled the city.

This spectacularly energetic recording indicates Rubinstein and the orchestra explosively burst upon the audience with immense energy. The musicologist Donald Francis Tovey was not describing this performance but his depiction of the concerto is perfectly apt.

'The orchestral writing is not only

symphonic, but is enabled by the very necessity of accompanying the solo

lightly to produce ethereal orchestral effects that are in quite a different

category from anything in the symphonies. On the other hand, the solo part

develops the technique of its instrument with a freedom and brilliance for

which Beethoven has no leisure in sonatas and chamber music.'

The opening as a type of cadenza

is in ways revolutionary for the time. The orchestra conducted by Czyż is immensely impressive throughout, both

dynamically and in detail, after the muscular entry of the Allegro theme

of the first movement. One could not help feeling that Rubinstein was successfully

calling on miraculous reserves of the fearsome energy of age and musical experience

in a type of irresistible protest against the normal, predictable physical

ravages of time. A dialogue emerges and not further cadenza, in fact Beethoven

directs the orchestra and soloist not to attempt one. I was reminded of that high

voltage line of the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas that both 'Rage, rage against

the dying of the light.' In fact, Beethoven himself once wrote to his

childhood friend Franz Wegeler a phrase which underpinned for me the entire Rubinstein

performance: 'I shall seize fate by the throat. It shall not wholly overcome

me. Oh, how beautiful it is to live – to live a thousand times.'

The second movement Adagio un poco mosso once again illustrated Rubinstein's unsurpassed poetic ability to paint the landscape of a yearning dream, intense in affecting poignancy. Here we have the Beethovenian self-awareness of disillusionment and loss yet placed within a faint watercolour of shadowy optimism. One is reduced almost to tears at Rubinstein's sublime phrasing and tonal eloquence. Then a moment of theatrical drama. The music rests in apparent equanimity on a low note, gliding low by a semitone, suggesting possibilities of rising chords but the exuberant finale Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo blazes out with fire, symphonic energy and colour. Where does Rubinstein excavate this life force at his age? A type of sorcery or wizardry has overtaken the performance bursts over us. We almost embrace the jubilant dances of the Seventh Symphony.

This remarkable account was greeted by wild cheering and heroic shouts of appreciation from the audience.

Rubinstein retired from the stage at the age of 89. His last performance was in May 1976 at the Wigmore Hall in London, a venue he played for the first time some 70 years before.

As an encore Rubinstein chose to play a work he must have performed a thousand and more times, the 'Heroic' Chopin Polonaise in A flat major Op.53.

I found this completion a prodigious lesson of life and music. A rather fractured, human performance, deeply moving in its struggle and following directly the titanic emotional and sheer physical demands of the preceding concerti. This performance, after such monumental striving with Chopin and especially Beethoven, despite the missteps, was replete with existential truth of the nature of human mortality and resistance to the inevitable fading of the light as age flowers.

It affected me to the very core of my being, containing the imperfect nature of human existence, the foibles, the courage, the vices, the strengths, the excitement, the resistance to oppression and yes, overlaying all, the commanding, profoundly musical nature of his character and immortal pianism. Rubinstein once commented in reaction to a fine account of Chopin: 'An excellent performance altogether but where is the music?'

Here was a fitting farewell to the land of his birth. Such playing was in distant contrast to the often misguided Urtext perfectionism increasingly aspired to today, both in performance and recording, that can leave one frozen, unmoved, as if in ice.

|

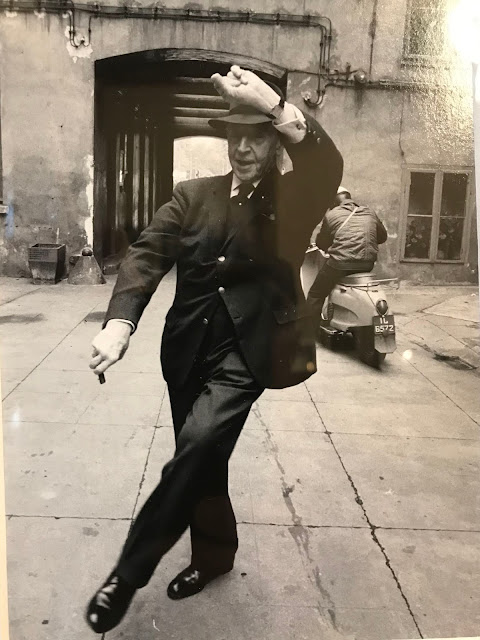

| Arthur Rubinstein, le grand seigneur, in regal regalia following his admission to the French Academy of Fine Arts This post may also be of interest covering the remarkable VI Arthur Rubinstein Piano Festival, Łódź , Poland 14-19 October 2019 http://www.michael-moran.com/2019/10/vi-arthur-rubinstein-piano-festival-odz.html |

Comments

Post a Comment