20th International Chopin and his Europe Music Festival 17th August – 08th September 2024

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Saturday 31.08.24 20:30

Witold

Lutosławski Studio of the Polish Radio

Christoph

Prégardien tenor

Julian

Prégardien tenor

Danae Dörken

piano

Chamber

Orchestra of the City of Tychy

Marek Moś

conductor

Ludwig van

Beethoven

Overture to

The Creations of Prometheus Op. 43

Franz

Schubert

Prometheus

(D. 674)

Greisengesang

(D. 778)

Der Vater mit

dem Kind (D. 906)

Erlkönig Op.

1 (D. 328)

Ludwig van

Beethoven

Overture to

“Coriolan”, op. 62 : Auszüge

„Christus am

Ölberg“, op. 85 : Meine Seele ist erschüttert

Franz

Schubert

Alfonso und

Estrella (D. 732)

Der Wegweiser

Op. 89 No. 20 (D. 911)

Totengräbers

Heimweh (D. 842)

Der

Doppelgänger No. 13 (D. 957 )

Nacht und

Träume Op. 43 No. 2 (D. 827)

Im Abendrot (D. 799)

The programme was created by two renowned tenors, father and son, Christoph and Julian Prégardien. They imaginatively joined Schubert Lieder, with Beethoven overtures and an aria from his sole oratorio. Extraordinarily, some songs were presented in an orchestral instrumentation by Brahms, Reger and Webern.

|

Schubert's songs were almost exclusively born from poetry. This may seem obvious but all too often the vital literary stimulation to musical creation is pushed to the sidelines in favour of extremely detailed analysis of the music. There are some 110 poets associated with Schubert, ranging from the genius of Göethe, Schlegel, Mayrhofer and Schiller to less demanding more popular emotional declarations. The sources could additionally be translations not only of foreign poets but also of Shakespeare, Petrarch and the ancient Greeks.

|

| Christoph Prégardien |

Many of Schubert's inner circle were writers and poets of course, sometimes the authors of opera libretti. Many German and Austrian poets, popular in their day, have fallen from favor, some passed into oblivion. This does not absolve us from the responsibility of realizing their words were sufficiently profound, entertaining or full of vitality to galvanize Schubert's musical creative inspiration. He in fact prided himself on his own literary judgment and discrimination in selections

|

| Julian Prégardien |

The profoundly melancholic and realistic approach of Death in Totengräbers Heimweh (D. 842). The dreams present in Nacht und Träume Op. 43 No. 2 (D. 827) and the noble Rückert song Greisengesang (D. 778). Songs were sung alone or as a father and son duet. Here are the words of Matthäus von Collin slightly altered by Schubert for musical reasons :

Night and Dreams

Holy

night, you sink down;

Dreams

too float down

like

your moonlight through space,

through the silent hearts of men

They

listen with delight,

cry

out when day awakes:

Come

back, holy night!

Fair dreams, come back!

Many of the poems were unknown to me in Schubert's settings save the terrifying and well-known Erlkönig Op. 1 (D. 328) which was almost psychically unbearably poignant sung and even subtly dramatized by this father and son.

|

| Julian Prégardien and Christoph |

The

Erlking

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (English Translation © Richard Wigmore)

Who

rides so late through the night and wind?

It

is the father with his child.

He

has the boy in his arms;

he

holds him safely, he keeps him warm.

‘My

son, why do you hide your face in fear?’

‘Father,

can you not see the Erlking?

The

Erlking with his crown and tail?’

‘My

son, it is a streak of mist.’

‘Sweet

child, come with me.

I’ll

play wonderful games with you.

Many

a pretty flower grows on the shore;

my

mother has many a golden robe.’

‘Father,

father, do you not hear

what

the Erlking softly promises me?’

‘Calm,

be calm, my child:

the

wind is rustling in the withered leaves.’

‘Won’t

you come with me, my fine lad?

My

daughters shall wait upon you;

my

daughters lead the nightly dance,

and

will rock you, and dance, and sing you to sleep.’

‘Father,

father, can you not see

Erlking’s

daughters there in the darkness?’

‘My

son, my son, I can see clearly:

it

is the old grey willows gleaming.’

‘I

love you, your fair form allures me,

and

if you don’t come willingly, I’ll use force.’

‘Father,

father, now he’s seizing me!

The

Erlking has hurt me!’

The

father shudders, he rides swiftly,

he

holds the moaning child in his arms;

with

one last effort he reaches home;

the child lay dead in his arms.

|

| Christoph Prégardien and Julien |

A deeply moving interpretation that lifted the Schubert song to the heights of artistic and metaphysical transcendence when father and son Prégardien sang their respective dialogues that appear in the poem. This dramatization by father and son was poetically and artistically transformational. This entire concert was unusual in that many songs had been arranged as duos. All wonderfully sung. Sometimes I felt as if they were singing with one voice.

The most moving aspect of the concert was the clear filial love that flowed like a glorious lyrical stream between the two tenors, father and son, especially in such a brutal work as the Erlkönig. The love between these two great artists, father and son, redeemed us all and lifted the entire concert onto another emotional plane of intimacy. The songs became an extraordinary type of recompense, a rare moment of healing for the sins of a murderous world. This was an expression of spiritual power and other worldliness, an expression of the strength and therapeutic power of true filial love, something I have never before experienced in any musical concert in my life.

Marek Moś the conductor and the Chamber Orchestra of the City of Tychy acquitted themselves with power and finesse. The alluring pianist Danae Dörken was the solo piano accompanist to some songs. Her tone was seductive and refined but powerful and declamatory when the occasion demanded.

|

Chamber

Orchestra of the City of Tychy

|

| Marek Moś |

|

| Danae Dörken |

Certainly I found this the most moving concert of the entire festival

For many years this father and son have been performing together. In June 2017, at the Frauenkirche in Dresden, I heard Christoph sing madrigals and operatic excerpts with his son Julien in a superb concert to commemorate the 450th birthday of Claudio Monterverdi. They were accompanied by Anima Eterna Brugge conducted by Jos van Immerseel. Father and son touched foreheads at the conclusion, a meeting of mind and heart, which was a deeply moving gesture.

An even more remarkable recital by Christoph Prégardien alone in Warsaw was given in 2019. I feel sufficiently moved to give you a link to that past concert and the recording that is now available.

You will need to scroll down through the festival posts to Saturday 17 August 2019 or put in a search for Prégardien.

http://www.michael-moran.com/2019/07/15th-chopin-and-his-europe-festival.html

Friday 30.08.24 20:30

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Collegium Vocale Gent

Philippe

Herreweghe artistic management

Et in Arcadia Ego

|

| The Course of Empire: The Arcadian or Pastoral State - Thomas Cole 1834 |

|

| Guercino - Et in Arcadia Ego 1618 |

.jpg) |

| Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) Et in Arcadia Ego (1626) |

Salamone Rossi (1570-1630)

Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi (1553-1609)

Luca Marenzio (1553-1599)

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643)

Sigismondo d’India (1582-1629)

The very word 'Arcadia' conjures so many seductive and erotic images of paradisiacal landscape and mythological figures. The blighted or consummated love of shepherds (Tyrsis) for shepherdesses or nymphs (Chloris) inhabiting a garden of delights but overshadowed by the thunderstorm of Death, perennially hovering near.

The instrumental music and vocal settings of poetry, perfect in intonation and conducted minimalistically by Philippe Herreweghe, took me unresistant into another dimension of this fabled region of the imagination. The madrigal was once a greatest musical gesture in what was once known as the avant-garde. It was contributed to by all the mannerist Mantuan composers featured here, most prominently by Claudio Monteverdi and Salomone Rossi. Such a divine programme of Renaissance Sinfonias and madrigals embraced us.

|

| The Polish Arkadia |

As I live in Poland, may I conjure the idea of the Polish Arcadia but in an eighteenth century context. The Italian Renaissance had an immense architectural and cultural influence in Poland. Of course, I adored the 'Arcadias' of Stourhead and Rousham in England but I am here now, living among the Polans (Polanie) or descendants of the people of the fields, as they were known in ancient history by the West. The country is far from Mantua in climate but perhaps not so far in temperament. The seductive nature of such picturesque ideas effortlessly cross boundaries of time and space.

I have often travelled to the

village of Nieborów near Żelazowa Wola (the village where Chopin was

born) about 50 kms from Warsaw where my favourite Polish country house and

pendant garden is situated, one of the great mansion and park ensembles in

Europe. Originally a baroque mansion designed by the Dutch architect Tylman van

Gameren it passed to the noble Radziwiłł family in the late eighteenth century.

Duke Michał Radziwiłł’s remarkable wife, Princess Helena, was a leader of

fashion in Warsaw concerning matters of landscape gardening and enlightened

patronage. The interior has an astonishing Dutch blue-tiled staircase and a

fine library. The lime avenue on the broad central axis of the mansion leads

across squares of lawn to a ha-ha opening onto a former deer park with a pine

forest in the middle distance. The whimsical placement of urns, sarcophagi,

tenth century statues of women from Sarmatian Black Sea tribes and a box garden

with an imperial eagle perched on a Roman column urges the wanderer to heroic

reminiscence of Polish history. I briefly sat on a garden seat with the

admonitory Latin inscription Non Sedas Sed Eas (Do not sit down

but go on). A fisherman was quietly waiting in a drifting dinghy on the lake

near an island.

About a mile from Nieborów, Helena Radziwiłł with the assistance of her

architect Szymon Bogumił Zug and the French painter Jean-Pierre Norblin de la

Gourdaine created the astonishing landscape garden of Arkadia over a

period of forty years. The ‘modern’ notion of a pastoral Arcadia is a

substantial transformation from the original pagan and brutish domain overseen

by rapacious Pan with horns, hairy haunches and cloven feet. Arkadia (Polish

spelling), a picturesque and elegiac garden of allusions, is in the tender

spirit of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and is one of the most extraordinary

‘sentimental’ eighteenth century gardens in Europe.

The garden was fertilised by many international influences. Changing vistas

were evoked by the golden pastorals of Claude Lorrain and the dramatic

classicism of Nicholas Poussin. The English Virgilian landscapes created by

William Kent at Stowe, Henry Hoare and Henry Flitcroft at Stourhead and

Alexander Pope at Twickenham all played their part. In Arkadia Horace Walpole

might have reminded us of those imitators of English gardens, his ‘little

princes of Germany’. The magnificent Enlightenment realm of Wörlitz, ruled by

Reason and Nature, was created in the late eighteenth century by Prince Leopold

Friedrich Franz of Anhault-Dessau. Here the wanderer could choose between the

route of ignorance and superstition or the route of esoteric knowledge.

Literature also played its vital part. The cult of nature, romantic mysticism

and antiquity were developed in the baroque pastoral romance Astrée by

Honoré d’Urfé and in ‘Julie’s garden’ of La Nouvelle Héloïse (1761)

by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (‘perhaps the most influential bad book ever written’

). The pervasive French sensibility of the time was greatly influenced by the

charm of those crowds of vanishing, marvellous creatures languishing in the

autumnal paintings of Jean-Antoine Watteau. Helena herself was fond of reading

the influential meditative poem The complaint; or, Night-thoughts on life,

death, and immortality by Edward Young (1683-1765).

The melancholy ghosts of dead renown,

Whispering faint echoes of the world's applause.

From Night IX

The many allegorical buildings in Arkadia are a labyrinth of encoded messages.

These ideas were propagated through the medium of Freemasonry. The garden was

conceived as an eloquent set of theatre scenes for the enlightened visitor,

evoking the vanished joys and lost ideals of the Enlightenment. The predominant

themes of are of Love, Happiness, Beauty and Death - ideas cultivated

through her eighteenth century sensibilité. On the Island of

Feelings set in a lake, flowers picked at the entrance to the park were placed

by visitors on altars dedicated to Friendship, Hope, Gratitude and Remembrance.

The walls of the High Priest’s Sanctuary are inset with Roman architectural

fragments and even an artificial sheep-pen alludes to a lost Virgilian past. An

inscription reads L’ésperance nourrit une Chimère et la Vie S’écoule (Hope

nourishes a Delusion as Life slips away).

‘Arkadia was all about memories, reveries, regrets and keeping civilization and

culture alive.’ Lying on the grass in the sun in a column of warm gold it was

not difficult to imagine delightful ‘Turkish’ fêtes galantes on the autumnal

lake. Willows trailed leaves in the still waters around the islands, swans

glided by while boats set sail for the île de Cythère. A world of intense

impressions, melancholy, poignancy and reflective thought, an excursion

particularly apposite in my present situation.

|

| The Polish Arkadia |

Friday 30.08.24 17:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Dang Thai Son

piano

Eric Lu piano

Sophia Liu

piano

Sinfonia Varsovia

Martijn

Dendievel conductor

Joseph Haydn (1732 - 1809)

Symphony in C major No. 38 "Echo (before 1769)

Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Concerto in F major for three pianos (K. 242) (1776)

This was a work written for three lady amateurs (the daughters of Countess Antonia Lodron) in the entertaining and affected galant style. It does not reach the commanding musical and artistic heights of his concertos for the solo instrument but under these six hands and with this orchestral conductor I found it a delightful confection. My two 'poets' Eric Lu and Kate Liu, glorious in tone and touch, were playing with virtuosic stylistic grace and affectation along with one of the great teachers and pianists of today, Dang Thai Son.

For an encore the pianists squeezed onto one stool, or perhaps two, and played a work for six hands. Unfortunately I have no idea what it was but it was highly entertaining !

Fryderyk

Chopin (1810-1840)

Variations in B flat major on a theme from Mozart’s ‘Don Giovanni’ (‘Là ci darem la mano’) Op. 2 (1828)

Chopin composed the ‘Là ci darem’ Variations in 1827. As a student of the Main School of Music, he had received from Elsner another compositional task: to write a set of variations for piano with orchestral accompaniment. As his theme, he chose the famous duet between Zerlina and Don Giovanni from the first act of Mozart’s opera Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni.

'In this opera overwhelming power and faultless seduction meet maidenly naivety and barely controlled fascination. (Tomaszewski)

In his famous first review of Chopin’s variations on Mozart’s ‘Là ci darem la mano’, Schumann gives us a striking description:

“Eusebius quietly opened the door the other day. You know the ironic smile on his pale face, with which he invites attention. I was sitting at the piano with Florestan. As you know, he is one of those rare musical personalities who seem to anticipate everything that is new, extraordinary, and meant for the future. But today he was in for a surprise. Eusebius showed us a piece of music and exclaimed: ‘Hats off, gentlemen, a genius! Eusebius laid a piece of music on the piano rack. […] Chopin – I have never heard the name – who can he be? […] every measure betrays his genius!’”

Chopin’s ‘Là ci darem’ Variations are classical in form with an introduction, theme, five variations and finale. They are a marvellous example of the style brillante and clearly influenced by Hummel and Moscheles.

It is well-known Chopin was obsessed with opera all his life, a fascination that began early. I felt Sophia Liu overwhelmed us with her youthful bravura and fabulous technique (she is only 16 I think). However, I did miss the feeling that a true Italian, Mozartian aria concerning the art of seduction was being sung with vocal intonation and an alluring, seductive and charming cantabile. For such a young lady to play with knowing erotic insight is rather a tall order but in compensation we were simply blown away by her keyboard genius. There will be much time to develop on this solid foundation through the heart and soul of experience!

Clara Wieck loved this work and performed it often making it popular in Germany. Her notorious father, who had forbidden her marriage to Robert Schumann, wrote perceptively and rather ironically of this work: ‘In his Variations, Chopin brought out all the wildness and impertinence of the Don’s life and deeds, filled with danger and amorous adventures. And he did so in the most bold and brilliant way’.

Liu began with a thoughtful introduction. I do feel as the piece moved forward that this pianist has a natural and deep musicality, true musical fluent speech. The projected energy at times was stunning, even frightening in sheer gifted talent. The work was replete with glittering style brillante execution, crystal articulation and Horowizian velocity. However, I felt each variation could have been delineated more clearly in mood and manner of execution from the next. But the progression of the structure remained astonishingly clear. What a golden road lies ahead for this young lady !

Mieczysław

Karłowicz (1876-1809)

The Eternal

Songs Op. 10 (1906)

I found this programming of the profoundly disturbing Eternal Songs rather a lurch from the cusp of sunny Classicism and Romanticism into our more modern times of alienation, existentialism and the metaphysics of Love and Death even opening into the space of the cosmos.

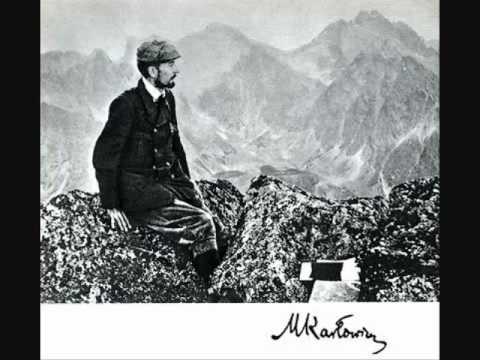

Although

familiar to musically educated Poles, the precocious late Romantic composer

Mieczysław Karłowicz [1876–1909] who died in an avalanche at the tragically

young at the age of 33, is relatively unknown outside the country. Certainly, his work is not sufficiently familiar to me to write in informed detail about

it. His symphonic poems cause him to be considered Poland's greatest symphonic

composer. At the time opposition to his compositions was violent. The music

historian Aleksander Poliński wrote of young composers that they '...have

now been affected by some evil spirit that depraves their work, strives to

strip it of individual and national originality and turn into parrots lamely

imitating the voices of Wagner and Strauss'. Karłowicz's compositions were

regarded as 'modernistic chaos' which made them unpopular with the

Polish public.

One needs to know the inspiration behind these three extraordinary philosophical works that provoke so much poignant thought. The melancholic Song of Eternal Longing concerns 'the desire that smolders in every human soul and possibly even inanimate matter'. That endless longing being the cause of all suffering. The second Song of Love and Death clearly was inspired by Wagner's Tristan und Isolde where love is ultimately fulfilled in death. Love and death are musically contrasted. 'Eros and Thanatos meet in an amorous embrace.' The final movement of this Op.10 is the Song of the Universe. Karłowicz sculpts a musical portrait of the Polish High Tatra Mountains that he was obsessed with both physically, through corporeal climbing and also by his ascent into the mind's stratosphere. One is forcibly transported by his music into this poetical landscape.

'And when I find myself alone on a steep summit, with only the sky's blue vault above me, and all around the peaks' hardened billows of snow, submerged in the sea of the plains - at such times I dissolve into the vast expanse around me, I no longer feel myself to be a separate individual. [...] they (the mountains) give me peace in the face of life and death, speaking of the eternal harmony of ,merging into the universe.'

So, a profoundly educational

concert for me, exploring the most significant Polish instrumental and

orchestral music between Chopin and Szymanowski. I felt Karłowicz to be a major

composer whose creative work was brutally interrupted by Nature in an avalanche

whilst pursuing his understandable passion (listening to the aspirations within

his compositions) of mountain climbing.

Thursday 29.08.24 19:0

Royal Castle

Harpsichord Recital

Andreas Staier harpsichord

The instrument was built by the distinguished maker Bruce Kennedy based on a famous 1624 Ruckers (Colmar) double manual ravalement

This was a most interesting programme assembled by the distinguished harpsichordist around different styles of composition for the instrument.

Stylus Phantasticus

Georg Böhm

(1661-1733)

Prelude, Fugue, and Postlude in G minor (1705-1713)

A remarkable set of works by a much underrated keyboard composer

|

The baroque

organ in the Johanniskirche, Lüneburg where Böhm was principal organist

Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Prelude and Fugue in B flat major (BWV 866)

Staier has mastered the style of this composer for the harpsichord although many of these works would probably have been first performed on a clavichord

'... in Stylo Francese'

François Couperin (1668-1733) - perhaps my favorite composer for the harpsichord. He understood and was fascinated and explored the rich sound of his chosen instrument in much the same way as Chopin by the piano. Couperin had a similar aristocratic style of composition that had an immense influence on composers in Europe. Wanda Landowska wrote about the similarities between Chopin and Couperin as did the great scholar Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger.

Second

livre de pièces de clavecin

I La

Raphaéle - Performed with

great style and appropriate seriousness - a great musical work modeled on an

evocation of the great Renaissance artist

IV Gavotte

Johann

Sebastian Bach

Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp major BMV 882 (1744)

The influence of the French style is pronounced in this work

'.... alla Maniera Italiana'

Domenico

Scarlatti

Sonata in

A major, K 208 A cantabile composition

probably composed for the Cristofori early piano owned by Queen Maria Barbara

Sonata in A major, K 209 The pendant was more active rhythmically

Johann

Sebastian Bach

Prelude and Fugue in C sharp minor (BWV 873) 1744

A quite wonderful performance of this familiar work

Fantasia Cromatica

Jan

Pieterszoon Sweelinck

Fantasia Cromatica SwWV 258

Another splendid and much underrated composer except of course by the cognoscenti

Johann

Sebastian Bach

Prelude and Fugue in A minor (BWV 889) 1744

'...und andere Galanterien...

Wilhelm

Friedemann Bach

Polonaise in

F major

Polonaise in F minor

Bach's favourite son and significant composer of Polonaises. Suffered from the foibles of an active and rich sensual life. I love his compositions so rarely performed.

Johann

Sebastian Bach

Prelude and Fugue in F minor (BWV 881)

Momento mori

Johann

Jacob Froberger

Méditation faite sur ma mort future (FbWV 611a)

One of the greatest of composers of deeply moving, profound existential music that touch the deepest recesses of the heart and soul.

Johann

Sebastian Bach

Prelude and Fugue in B minor (BWV 869)

As an encore the Bach E major Prelude and Fugue from Book II of the WTC

|

| Michael Moran privileged to speak to Andreas Staier about Francois Couperin |

Wednesday 28.08.24 20:30

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Francesco

Piemontesi piano

Kammerorchester Basel

Antonio

Viñuales Pérez conductor (Principal 2nd violin)

I would like to quote the Mission Statement of the superb Kammerorchester Basel at the outset of this review:

'We are an innovative, artistically independent and creative top ensemble. With our love and passion for music, we break new ground, transcend boundaries and inspire our audiences. We are constantly developing our own historically oriented sound.'

Programme

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel

(1805-1947)

Overture in C major (1852 or 1856)

I have often written recently concerning the rehabilitation of female composers scandalously neglected in the nineteenth century owing to mere social prejudice not lack of musical genius.

http://www.michael-moran.com/2024/01/the-contrarious-moods-of-men-review-of.html

Fanny was the elder sister of Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and was rather a victim of the suppression of talented women in the nineteenth century. Her famous brother included some of her songs in his own collections in order to have them heard. Of the 400 works she wrote only a few are now emerging from the shadows of neglect after her fearless declaration to the music publisher as the dreaded female composer.

This was the only purely orchestral work she completed and as such was fascinating to hear. It indicated her interest in her bother Felix's preoccupation with the sea and seafaring. He wrote a concert overture Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage. The work indicated and underlined the formidable gifts of the Mendelssohn musical family and the crying need for her resuscitation.

Before I personally assess the performance, I would just like to quote from my impressions of Francesco Piemontesi the first time I heard him in August 2011 at the Duszniki Zdrój International Chopin Festival. He was 28. How far he has developed in musical maturity even since then !

The period Piemontesi had spent with Alfred Brendel became clear from the very opening bars of Beethovens' Sonata in A Major Op. 101 and yet it was is own voice. This emotionally affecting work is Beethoven at his most intimate and sensitive. Piemontesi brought a classical poise to the work, wonderfully married to warm emotional life.

From the outset it became apparent that he is a deeply sensitive musician, a true poet of the instrument, who has cultivated a refined tone, a far lower level but much wider range of expressive dynamics and articulation than many young artists. Too many young players begin so loudly and choose such fast tempi they literally have nowhere to go when they require it, finding themselves trapped in a cul de sac of sound entirely of their own making.

The entire second half of the concert was taken up with the Sonata in A major D. 959, one of the last sonatas by Schubert. This was a truly great performance and a profound emotional experience for the entire audience here at Duszniki. The pianist collected us around his soul. The range of expression was remarkable, the movement from one reality to another or one dream to another, the flashes of memory and sense of bleak alienation produced an atmosphere in the hall the like of which is rarely experienced in a public concert. The silence was palpable - one could hear pin drop even between movements - not a sound - for the entire long duration of the sonata.

The silences within the work itself, within the harmonic and rhythmic structure (so important in Schubert's last sonatas and all music for that matter) were deeply utilized by this pianist as 'blocks of sound' full of meaning. They were such pregnant silences, silences that expressed the deeply troubled, febrile yet poetic spirit and soul of Schubert - a man searching for a secure anchorage as his life slipped away.

As someone mentioned to me later, his playing moved one in a similar way to the spiritual refinement, modesty, musical commitment and sensitivity of Dinu Lipatti or Michelangeli. This will be one of my most memorable musical experiences.

Ludwig van

Beethoven

Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58

Begun in 1805, it was completed early the next year and premiered on December 22, 1808, as part of the famous Akademie in the Theater an der Wien.

It was Beethoven’s last appearance as a concerto soloist and the basis of an extraordinary anecdote. The composer Louis Spohr recounted a description told to him by Ignaz Xaver Seyfried, music director at that venue at that time. The concert lasted some four hours. The audience sat with great determination in the unheated concert hall in the freezing winter.

“Beethoven

was playing a new Pianoforte-Concerto of his, but forgot at the first tutti

that he was a solo player, and springing up, began to direct in his usual way.

At the first sforzando he threw out his arms so wide asunder, that he knocked

both the lights off the piano upon the ground. The audience laughed, and

Beethoven was so incensed that he made the orchestra cease playing, and begin

anew.

Fearing a repetition of the accident, two boys of the chorus placed themselves on either side of Beethoven, holding the lights. One of the boys innocently approached nearer, and when the fatal sforzando came, he received from Beethoven’s right hand a blow on the mouth, and the poor boy let fall the light in terror… If the public were unable to restrain their laughter before, they could now much less, and broke out into a regular bacchanalian roar. Beethoven got into such a rage that at the first chords of the solo, he broke a dozen strings.”

This was a superb performance by Piemontesi and superb Kammerorchestra Basel directed by Antonio Viñuales Pérez 'conductor' and Principal 2nd violin. One of the finest I have ever heard from any pianist and orchestra. The dynamic balance and integration of piano and orchestra were eloquently judged.

Allegro moderato

The opening chord, so difficult for a pianist to manage dynamically dolce, was soft, poised and set an almost dreamlike atmosphere, a domain sensitized to the secrets of the forest. Piemontesi communicate directly and intimately with the orchestra from the outset with both eye contact and his body language. The result was a perfectly balanced symbiosis of dynamic and stylistic statements and response.

His glorious tone and velvet touch with minimal pedal suited the underlying classical nature of the work yet maintaining gestures of romanticism attempting to gently break free from the classical braces. The tempo and feeling of improvisation gave one the feeling of invention at the very moment. The immortal cadenza to this movement was expressive and indicated a highly refined but supremely virtuosic keyboard mastery.

Andante con moto

The second movement was simply and lyrically sublime and I do not use these words lightly. Accompanied only by the orchestral strings, the theme is well known to all music lovers. The movement has often been compared to Orpheus taming the wild beasts with his music. The underrated pupil of Beethoven, Carl Czerny, observed:

'in this movement (which, like the entire concerto, belongs to the finest and most poetical of Beethoven’s creations) one cannot help thinking of an antique dramatic and tragic scene, and the player must feel with what movingly lamenting expression his solo must be played in order to contrast with the powerful and austere orchestral passages.'

This magnificent orchestra was occasionally declamatory and powerful which contrasted movingly and dramatically with the rich harmonies and cantabile phrases of the piano part. The cellos and basses maintained an ethereal pianissimo. Until the opening of the final movement, one has been seduced into a somnambulistic dream world by the emotional, implied restraint of this concerto. Piemontesi was supremely lyrical yet not sentimental in the profound poetry and shifting poignant moods he brought to this movement. A remarkable serenity pervaded and an inspired peace and calm suffused the whole.

Rondo. Vivace

Piemontesi brought spectacular, authoritative, assured and exciting rhythm to the Finale. Trumpets and drums sound as we transition into this exuberant Rondo, like the flash in sunlight off a mountain spring at its source.

Again I felt how Piemontesi achieved a perfect balance in this great composition, a work which hovers beguilingly like a humming bird over the cusp of classicism and rich romanticism. The orchestra were outstanding, even supremely transformed, by the energetic, musically committed and expressive, persuasive conducting by Antonio Viñuales Pérez.

There was a wild audience reaction and an instant standing ovation at the close.

Emilie

Mayer (1812-1883)

Symphony No. 5 in F minor (1852 or 1856)

I was unfamiliar with this other

female composer on the programme, Emilie Mayer, who was a friend of Fanny

Hensel. She was from a wealthy family and a piano prodigy. Her father committed

suicide on the 26th anniversary of his wife's funeral left Emilie a substantial

legacy. Unlike Fanny who restricted herself to chamber works, she embarked on a

serious career as a composer and unusually for a lady, writing in all the great

genres. She became quite famous in her day as a substantial female composer.

This symphony I found highly skilled, full of charm and drama, yet in the final

analysis, not expressive of deeper emotional meaning if that is what you are

searching for.

* * * * * * * * * *

Tuesday 27.08.24 20:30

Moniuszko Hall of the Teatr Wielki – Polish National Opera

Vilde Frang violin

Kaunas State Choir

London Symphony Orchestra

Robertas Šervenikas choir manager

Antonio

Pappano conductor

Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Violin Concerto in B minor Op. 61 (1905-1910)

Edward Elgar is considered one of the greatest and most popular of English composers. He was at the height of his compositional genius around 1910. Having created 'The Dream of Gerontius', the Enigma Variations, the First Symphony and the Pomp and Circumstance Marches he was then at a high point in the estimation of the public. Elgar had been making sketches of a violin concerto for a long time.

He had begun work on a violin concerto in 1890, but he was dissatisfied with it and destroyed the manuscript. In 1907 the greatest violinist of the day, Fritz Kreisler, admired Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius and asked him to write a violin concerto. Two years earlier, Kreisler had told an English newspaper:

If you

want to know whom I consider to be the greatest living composer, I say without

hesitation Elgar... I say this to please no one; it is my own conviction... I

place him on an equal footing with my idols, Beethoven and Brahms. He is of the

same aristocratic family. His invention, his orchestration, his harmony, his

grandeur, it is wonderful. And it is all pure, unaffected music. I wish Elgar

would write something for the violin.

Elgar reconsidered. He engaged W. H. 'Billy' Reed, leader of the London Symphony Orchestra for technical advice while writing the concerto as well as advice as to how to render the brilliance more attractive by Fritz Kreisler.

The premiere was at a Royal Philharmonic Society concert on 10 November 1910, with Kreisler and the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by the composer. Reed recalled, 'the Concerto proved to be a complete triumph, the concert a brilliant and unforgettable occasion' .So great was the impact of the concerto that Kreisler's rival, the great Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe, spent time with Elgar going through the work. There was great disappointment when contractual difficulties prevented Ysaÿe from playing it in London.

The concerto was Elgar's last great popular success.

Certainly, the concerto is dedicated to Kreisler, but the score also carries the enigmatic Spanish inscription, 'Aquí está encerrada el alma de ....' ('Herein is enshrined the soul of .....'), a quotation from the novel Gil Blas by Alain-René Lesage. The five dots are one of Elgar's enigmas, and several names have been proposed to match the inscription. The Elgar biographer Jerrold Northrop Moore suggests that the inscription does not refer to just one person, but enshrined in each movement of the concerto are both a living inspiration and a ghost: Alice Stuart-Wortley and Helen Weaver in the first movement; Elgar's wife and his mother in the second; and in the finale, Billy Reed and August Jaeger ("Nimrod" of the Enigma Variations).

Vilde Frang is a award-winning young violinist of deep musicality and a high degree of sensitivity which made itself clear in the Elgar concerto. There was great emotional urgency in the haunting solo violin opening Allegro. The so-called 'Wildflower' theme and tone played by Frang was deeply poetic on the Guaneri del Gesù instrument of 1724. The familiarity of the orchestra and Pappano with Elgar was abundant in the fluent and meaningful phrasing in a fine symbiotic attachment to Frang.

The second movement begins with a melody that reminds me of wind rustling through English oaks. Frang rendered the music with extreme gentleness which was emotionally deeply moving. In a letter to Alice Stuart-Wortley, Elgar labelled it ‘Windflower’, his nickname for her. The Andante was played with refinement and as a love song with superb control of the eloquent tone and delicacy possible on this glorious Guaneri. Elgar did say of the Violin Concerto: 'It’s good! Awfully emotional! Too emotional, but I love it. Full of romantic feeling.' I felt Frang must have read this sentence.

Both orchestra and soloist were without peer in the challenging final movement. After brilliant passages for the orchestra and violin we have a curious period of rumination concerning events of the past ? The cadenza is usually played alone by a soloist in a musical work. Here the violin is accompanied by the orchestra in a type of evocation of nostalgic memory. H.C. Colles (1879-1943), for 32 years chief music critic of The Times, writer on music and organist said: 'Elgar dwells on his themes as though he could not bear to say good-bye to them, lest he should lose the soul enshrined therein.' Frang was superb in this work and received an enthusiastic ovation

Gustav Holst

Symphonic

Suite 'Planets' Op. 32

I can think of no other single work by an English composer that has achieved similar widespread fame than The Planets Suite by Gustav Holst. He created The Planets between 1914 and 1917. This partly stemmed an interest in astrology and partly a desire to produce a large scale work for orchestra. and also from his determination, despite the failure of Phantastes, to produce a large-scale orchestral work. He told the English writer Clifford Bax in 1926 that The Planets:

'… whether it’s good or bad, grew in my mind slowly—like a baby in a woman’s womb ... For two years I had the intention of composing that cycle, and during those two years it seemed of itself more and more definitely to be taking form.'

Holst's biographer Michael Short and the musicologist Richard Greene both think it likely that the inspiration for the composer to write such a suite for large orchestra was the example of Schoenberg's Fünf Orchesterstücke (Five Pieces for Orchestra) performed in London in 1912 and 1914.

'... ignoring some important astrological factors such as the influence of the sun and the moon, and attributing certain non-astrological qualities to each planet. Nor is the order of movements the same as that of the planets' orbits round the sun; his only criterion being that of maximum musical effectiveness.' (Short p. 122)

What a privilege to hear Antonio Pappano conduct this work with the LSO !

'Mars the Bringer of War' was overwhelming from its quiet opening to a quadruple-forte with dissonant climax in percussive impact and driving rhythm. I have never experienced a musical physical impact to equal it in concert or recording. Short writes that battle music 'had never expressed such violence and sheer terror' One could not help but reflect on the present horrors.

'Venus, the Bringer of Peace' The movement opens Adagio with a solo horn theme answered quietly by the flutes and oboes. According to Imogen Holst, Venus 'has to try and bring the right answer to Mars. A second theme is given to solo violin. Short calls Holst's Venus 'one of the most sublime evocations of peace in music'. Incidentally, I was born under this most fortunate of stars. 'Mercury, the Winged Messenger' is a short pictorial movement of speedy flight, even close to programme music that depicts a scherzo movement. The LSO soloists for solo violin, high-pitched harp, flute and glockenspiel were prominently featured at the highest level of musical performance. 'Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity' marked allegro giocoso is packed with exuberance 'abundance of life and vitality'. Papanno also highlighted the feelings of nobility in the andante maestoso concluding with the extraordinary richness in full, tight ensemble of this orchestra.

'Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age' This was Holst's favourite movement of the suite. Colin Matthews describes it in his CD notes as 'a slow processional which rises to a frightening climax before fading away as if into the outer reaches of space' As the work opens, the LSO virtuoso flutes, bassoons and harps played a theme suggesting a ticking clock. The trombone section introduce a solemn melody (the trombone was Holst's own main instrument) was taken up by the full orchestral power of the LSO. Papanno understood this planet to perfection. 'Uranus, the Magician' The movement began with powerful brass allegro motifs from this commanding section of the orchestra. This is followed by various 'merry pranks' building to a tremendous LSO quadruple forte climax with a prominent organ glissando. has elements of Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique and Dukas's The Sorcerer's Apprentice, in its depiction of the magician who 'disappears in a whiff of smoke as the sonic impetus of the movement diminishes from fff to ppp in the space of a few bars' (Short pp.130-131) 'Neptune, the Mystic' opens with flutes joined by piccolo and oboes, with harps and celesta more prominent later. The beautiful, unearthly intonation of the Lithuanian Kaunas State Choir then joined the orchestra. In the end, the orchestra fell silent and the unaccompanied voices bring the work to a poetic pianissimo conclusion. Here the final eternal nature of cosmic silence, as powerful in expression as a moment in space filled with sound.

As an encore,

Nimrod from the Elgar Nimrod Variations brought me to tears and emotional

dislocation as I entered a world of intense nostalgic recall for my previous long

life in London and England before I moved to Poland and Warsaw.

Monday 26.08.24 20:30

Moniuszko Hall of the Teatr Wielki – Polish National Opera

Bruce Liu piano

London Symphony Orchestra

Antonio Pappano conductor

Fryderyk Chopin

Piano Concerto in E minor Op. 11

Jean Sibelius

Symphony No. 1 in E minor Op. 39

Some of you may have already this but I make no apology for repeating it !

Some important cultural context for you concerning the E minor Piano Concerto Op.11 before reading the review

|

| The Young Chopin in 1829 Ambroży Mieroszewski (1802–1884) |

|

| Warsaw Panorama from Praga 1770 - Bernado Bellotto |

Chopin wasted no time in composing his next concerto in 1830 after that in F minor.

In many ways the E minor concerto revolves around the exalted Romanze. Larghetto central movement. He elucidated its inspiration to his friend Tytus Woyciechowski: ‘Involuntarily, something has entered my head through my eyes and I like to caress it’.

The Warsaw premiere audience numbered around 700. ‘Yesterday’s concert was a success’, wrote Chopin on 12 October 1830 to Tytus ‘A full house!’ Two young female singers also performed at the concert conducted by that controversial figure in Warsaw musical life, Carlo Soliva. Contemporary programming was unimaginably different to 2021. After the Allegro had been played to ‘a thunderous ovation’, Chopin sacrificed the stage to a singer [‘dressed like an angel, in blue’], Anna Wołkow. Typical of the pressing personality of Soliva, she sang an aria he had composed.

The other young singer was Konstancja Gładkowska. Chopin wrote as descriptively as always: ‘Dressed becomingly in white, with roses in her hair, she sang the cavatina from [Rossini’s] La donna del lago as she had never sung anything, except for the aria in (Paer’s) Agnese. You know that “Oh, quante lagrime per te versai”. She uttered "tutto desto” to the bottom B in such a way that Zieliński (an acquaintance) held that single B to be worth a thousand ducats’.

This 'farewell' concert was only three weeks before Chopin left Warsaw and the subsequent November 1830 uprising burst upon the city. ‘The trunk for the journey is bought, scores corrected, handkerchiefs hemmed… Nothing left but to bid farewell, and most sadly’. Konstancja and Frycek exchanged rings. She had packed an album in which she had written the words ‘while others may better appraise and reward you, they certainly can’t love you better than we’. Only two years later, Chopin added: ‘they can’ which speaks volumes.

An introductory book on the concertos and their context I cannot recommend more highly:

Chopin - The Piano Concertos by John Rink (Cambridge Music Handbooks 1997)

Fryderyk Chopin

Piano Concerto in E minor Op. 11

Bruce Liu piano

London Symphony Orchestra

Antonio Pappano conductor

Under the profoundly musical conductor, Antonio Pappano, the remarkable London Symphony Orchestra opened the work with a powerful declaration of intent. How this pianist has matured in sensibility and Chopineque understanding, le climat de Chopin as the pupil of Chopin, Marcelina Czartoryska, penetratingly described it. His recent expressive emotional development in interpretation has been so significant and uplifting to hear! The English academic musicologist and Chopin authority, Jim Sampson, perceptively writes that the concerto allows the pianist to be a showman, warrior and poet. Liu rises to these varied roles.

Liu's entry was crystal clear yet lyrical. His LH was prominent in counterpoint and his tone in bel canto quite ravishing and emotionally moving. The style brillante was even more intense, light, airy and virtuosic than in the competition. This was as it was understood to be in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

One could hear all the LH detail which added significant depth to the soundscape and exegesis of various themes. His tone and touch are now even more elegant, expressive, rich and graceful. There is distinguished refinement, subtle dynamic sensitivity and aristocratic bon gout in this playing. As before, a light, glistening glitter like pearls falling on glass were scattered over us. His thirds are spectacular and only comparable to Horowitz.

I felt the he had plumbed far more deeply than four years ago, the emotional tragedy which occasionally and painfully fissures this movement. There was quite exceptional co-ordination with the outstandingly musical and virtuosic London Symphony Orchestra under their immensely gifted and sensitively sympathetic, on occasion grand and operatic conductor, Antonio Pappano. The dynamic balance with the Fazioli instrument was perfectly judged by Pappano, who is himself a fine pianist.

Romanze. Larghetto

Great simplicity, a touchstone of the composer, was evident here in a seductive fashion. The aria, a true nocturne taken at dusk in a garden or in moonlight on the still waters of a lake, moved forward in clusters of expressive tension and relaxation. This was true singing on the piano. A lovely duet with the bassoon evolved.

Rich in colour, his phrasing was beautifully sculptured into touching poetic shapes replete with emotional expression of an affecting and poignant kind that suffuses adolescent, unrequited love. For me he had moved one expressive dimension deeper in sensibility than his competition performance. The movement faded with fatalistic inevitability into the dreamworld from which it had originally emerged. A magician who continues to hypnotized us with piano sound.

Rondo. Vivace

As in the competition, this remained a perfect krakowiak both in engaging and vitalizing rhythm and embracing the Polish spirit of dance. The expression was so gloriously varied in articulation, colour, timbre, dynamic and above all, the affected charm of the true style brillante. Eloquent counterpoint in the LH balanced with the RH once more spoke volumes. The Fazioli instrument supported him and the internally fizzing yet richly rounded tone and incandescent sound world he created to perfection.

There was so much life, verve and vivacity invested in the variegated expressiveness. This was fiery energy without crudity of tone or dynamic in an exuberant display that one was privileged to hear live. Some running, high velocity passages were executed with extreme feather-like articulation and delicacy at a pianissimo dynamic.

This type of overwhelming execution I have only heard in recordings of the late nineteenth century masters of the instrument such as Josef Lhévinne, Leopold Godowski or Vladimir de Pachmann. A tremendous, overwhelmingly symphonic conclusion arrived in the coda. One must also reflect on the genius of Chopin in winding up the virtuosic tension to such a formidable pitch of thermodynamic intensity. The London Symphony under Pappano also captured the rhythm, dance and joy to perfection but with unimaginable grace and refinement of sound.

This account of the work was without doubt the finest with modern instruments I have ever heard - and I have heard hundreds by now. The audience were quite beside themselves with enthusiasm and leapt to their feet, shouting their emotional release for ten minutes at least. I have only experienced this once before with Vladimir Horowitz in London (but actually this was on his entrance to the stage before he played a note!).

The first charming encore was a perfect period pendant to the concerto, the so-called 'Pendolino' Nocturne in E-flat major Op.9 No.2 in by Chopin arranged for violin (Sarasate) and piano. The work was played by the orchestra concertmaster Marquise Gilmore Benjamin. Bruce provided a gentle piano accompaniment that scarcely existed yet provided a tonal base over which the violin sang.

There were even moments of relaxing humour. Incidentally, for non-Poles the 'Pendalino' nocturne is so named because this was a Chopin piece chosen for the internal sound system for passengers on the Pendalino high-speed intercity trains crossing Poland.

The second encore, only obtained by an indefatigable applauding audience, was the Chopin Etude in G-flat major Op.10 No.5 executed with glittering style brillante articulation.

This was a fabulous concerto performed at the highest musical level which remains in an elevated position on my list of lifetime memorable musical experiences.

Jean Sibelius

Symphony No. 1 in E minor Op. 39

Sibelius was regarded as a national hero in Finland but his reception outside his native land was more mixed. He felt rather a time bandit and isolated from the avant garde modernist musical movements of his day that shuffled away from Romanticism. This adherence to 'the past' extracted a high price personally and psychologically in terms of alcoholism, depression and diminishment of self-esteem. He knew deeply he was a musical genius but wrote 'Only very few understand what I have done and want to do in the world of the symphony. The majority have no idea what it is about.' [...] ’Isolation and loneliness are driving me to despair.' he wrote in the 1920s.

Twenty years later his diary of 1943 reveals his horror at the race laws of Nazi Germany but he wrote of private agonies: 'The tragedy begins. My burdensome thoughts paralyze me. The cause? Alone, alone. I never allow the great distress to pass my lips.' In the 1920s and 1930s he became internationally famous, even adored as 'the new Beethoven' in New York and became a celebrity. Like many, this new-found fame he found difficult to deal with and disorientating. The avant-garde were highly intolerant of his music.

Theodor Adorno, the renowned but controversial German philosopher and musicologist, supporter of Arnold Schoenberg and the avant-garde, wrote intensely critically for a sociological think tank called the Princeton Radio Research Project: 'The work of Sibelius is not only incredibly overrated, but it fundamentally lacks any good qualities [...] Is Sibelius's music is good music, then all the categories by which musical standards can be measured - standards which reach from a master like Bach to the most advanced composers like Schoenberg - must be completely abolished.'

Much thanks to Alex Ross on occasion, from his remarkable book The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth

Century (New York 2007)

The premiere of the First Symphony in E minor and the final version of his well-known Finlandia, coincided with a developing Finnish nationalism. As we have seen expressed in the 2nd. Symphony, Finland’s autonomy under Russian rule was threatened by Tsar Nicholas II. He attempted to suppress the country’s language and culture. Sibelius’s music and the paintings of Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931), were seen as symbols of resistance. Sibelius himself denied any programme or political message in his symphonies, asserting they were pure abstract music.

|

| A Finnish lake by Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931) |

He met many of the famous contemporary composers – Debussy, Schoenberg, Strauss and famously Mahler. Sibelius maintained his conviction in discipline, 'formal rigours', coherence and 'profound logic' in symphonic construction and relevance, whilst Mahler declared that the symphony 'must be like the world, it must embrace everything'.

The work was completed in 1899 when Sibelius was 34. It has four movements.

I. Andante, ma non troppo –

Allegro energico

II. Andante (ma non troppo

lento)

III. Scherzo: Allegro

IV. Finale (Quasi una fantasia): Andante – Allegro molto – Andante assai – Allegro molto come prima – Andante (ma non troppo)

This was a remarkably rich and lush performance by the London Symphony Orchestra under Antonio Pappano. In the Andante, ma non troppo – Allegro energico, the opening rumble of the timpani and lone, melancholic solo clarinet give way to sublime melodies, stunning brass, woodwind and harp reminding reminiscent of the Tchaikowsky Pathétique Symphony. The percussion section of this orchestra is quite extraordinary. The tempestuous orchestration suited the extraordinarily dense, tight, mahogany thrilling string sound of the LSO. The nostalgic yearning and colours of the Andante were beautifully directed by Pappano. The Sibelius scholar Erik Tawaststjerna has described the Scherzo movement as firmly in the Bruckner tradition. The timpani again came to the fore in the opening.

The Finale is replete with majestic themes that were magnificent with these forces. Pappano directed the interplay of the various instrumental groups in a quite extraordinary manner to hear and absorb musically. Under this a relentless, almost ominous pedal hovers. The final pizzicato bars almost took me onto the Nordic ice. A more enriching performance and interpretation I can scarcely imagine.

Sunday 25.08.24 19:00

Moniuszko Hall of the Teatr Wielki – Polish National Opera

Concert version

Stanisław Moniuszko

Straszny dwór [The Haunted Manor]

Karen Gardeazabal soprano

Agata Schmidt mezzo-soprano

Agnieszka Rehlis mezzo-soprano

Petr Nekoranec tenor

Artur Ruciński baritone

Paweł Konik baritone

Mariusz Godlewski baritone

Rafał Siwek bass

Krystian Adam tenor

Zuzanna Nalewajek mezzo-soprano

Paweł Cichoński tenor

Podlasie Opera and

Philharmonic Choir

Violetta Bielecka choir

manager

Fabio Biondi conductor

The principal […] field of Mr Moniuszko’s activity as a compose is dramatic music; his favourite genre is French opera, created by Gluck, refined with Italian improvements by Méhul and Cherubini, later enriched with the treasures of harmony and drama of the German opera, disseminated so widely by Catel, Boiledieu, Auber, Hérold and Halévy, the sounds of the French opera are heard today from the stages everywhere across Europe. Indeed, music of this kind seems to be much more to our taste than the studied, dreamy-philosophical German style: we are so fond of this gaiety, this lightness that does not exclude the true drama, melodiousness, grace and naïveté—the ingredients of the good French opera.

[Stanisław Lachowicz, “Moniuszko,” Tygodnik Petersburski 13 (1842), No. 80. Quoted from Grzegorz Zieziula, From Bettly in French to Die Schweizerhütte in German: The Foreign-Language Operas of Stanisław Moniuszko]

Stanisław

Moniuszko was born into a family of Polish landowners settled in Ubiel

near Minsk in present day Belarus and showed the customary precociousness

of genius. He studied composition and conducting with Carl Friedrich

Rungenhagen in Berlin in 1837 and later worked as an organist in Vilnius. He

traveled often to St. Petersburg where he met the great composers of

the day (Glinka, Balakirev, and Mussorgsky) and also Weimar where he met

Liszt and then Prague where he made the acquaintance of Smetana. His

first recently discovered (2015) comic opera in two acts composed in Berlin was

entitled Der Schweizerhütte (the Swiss Cottage).

In 1848 he visited Warsaw and met the writer, actor and director Jan Chęciński who became the librettist of arguably Moniuszko’s greatest operas, Halka and Straszny Dwór (The Haunted Manor), both infused with the fertile theme of Polish nationalism. Halka was premiered with great success in Warsaw in 1858 (10 years after the concert version performance in Vilnius!) and then later in Prague, Moscow and St. Petersburg. Moniuszko became an oversight success in the manner of Lord Byron after the publication of Childe Harold. He then began to concentrate on operas that eschewed Polish themes.

For example Moniuszko for some time had been fascinated with the class system in France as also the caste system in India as depicted in the play Paria by Casimir Delavigne (1793-1843) which he had translated from the French. He also desperately wanted an operatic success on the stages of Paris, spurred on by the successful operas of Meyerbeer. He had toyed with the idea of Paria for some ten years before it was finally premiered in 1868. The Overture is a magnificent evocative piece of 19th century orchestral writing.

Until at least 1989, this 'iron cultural curtain' effectively concealed the existence of Stanisław Moniuszko and his operas for directors, producers and audiences in the West. However, I feel sure that more imaginative, fully costumed, opulent staged production of his more obscure or forgotten operas (rather than concert performances) with fine soloists of world renown would at least partially fulfil and validate all of Moniuszko's own immense and deserved hopes for an international reputation. Italian arias dominate traditional opera and French arias follow closely behind which leaves those composers writing and setting libretti in less common languages with a distinct sense of inferiority. Moniuszko remains central to a full understanding of Polish culture which is finally reaching its deserved place in the European world picture. He wrote 14 Operas, 11 Operettas, some 90 religious works in addition to over 300 songs, piano pieces, orchestral music and chamber music.

A long evening that in the harsh light of day attracted rather mixed reviews. This could well have been because the opera had been completely rethought musically in this concert version by Biondi. He is by now intimately familiar with the other operas of Moniuszko which even Polish melomanes may not have heard or seen in performance apart from isolated arias and overtures. Poles deeply identify with the emotions and even concealed political intentions of the opera Straszny dwór [The Haunted Manor] (it was banned by the Russians after only three performances). They have assuredly a deeply nationalist view of the work with close familiarity of how it should be performed and interpreted for them. Biondi redefined this in many ways musically which some may have found disturbing.

I will simply select highlights that moved me 'as a foreigner'. The plot is rather simplistic but makes its point forcibly! Rather than having me arduously outline it here, do read:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Haunted_Manor

The baritone Artur Ruciński gave a majestic, resonant performance of the Sword-bearer's Act II aria Kto z mych dziewek (Who of my girls...) from the opera. The strength of this voice indicated the powerful presence of the singer and was enthusiastically received by the audience

|

| Artur Ruciński (Miecznik) |

The soprano Karen Gardeazabal was deservedly popular with the audience (wildly so) singing the character Hanna's recitative and the demanding aria 'Do grobu trwać w bezżennym stanie' (A lament that she may die before getting married) from Act IV of the opera.

|

| Karen Gardeazabal (Hanna) and Agata Schmidt (Jadwiga) |

|

Agnieszka Rehlis (the Chamberlain's Wife, Old woman) |

|

| Karen Gardeazabal (Hanna) |

The fine tenor Petru Nekoranec sang the character Stefan's resonant, tender yet dramatic one of the most famous arias in Polish operatic literature from Act III, Cisza dokoła (Every corner of silence). This aria contains an extraordinary stroke of genius, which has a chime embedded in it as a carefully concealed subversive political statement concerning Sarmatian Poland - or so it seems to me. Partitioned Poland at that time existed as a sovereign nation state only in the minds of its citizens.

|

| Pawel Konik (Zbigniew) and Petr Nekoranec (Stefan) |

On 13 October 1865, the Gazeta Muzyczna i Teatralna wrote "In the third act there is this famous chime, which pleased the public. It is a polonaise closed only in eight bars, and written in an archaic style, resembling at least [Michał] Oginski. " Another journal, the Dziennik Warszawski on 30 September 1865 commented "But the main advantage of this act [...] is Stefan's aria with a chime. The very idea of combining several instruments, as: flute, harp, piano and bell [also harmonium], to imitate the voice of an old-fashioned chimes is a happy and original idea, all the more so as the beat of the clock is repeated in the echo, made by string instruments . The same melody, coming out of the clock, serves as a prelude to a beautiful aria.' Nekoranec made much of this great tenor aria in an impassioned and wrought delivery of carefully graded nuance and drama. I thought this aria quite remarkable having never heard anything resembling it in the Western canon.

Another fine moment was from the bass Rafał Siwek movingly sang the character Skołuba's aria Ten zegar stary (This old clock)also from Act III of the opera. The depth and richness of this voice and unflustered intonation were most striking in a deeply satisfying artistic performance.

|

| Rafał Siwek (Skołuba) |

Such a pity there were not surtitles in English. The libretto in Polish and English was excellent except that the font was tiny and could not be read in the dim illumination!

|

| Fabio Biondi and Europa Galant |

I found Fabio Biodi's orchestral conducting of Europa Galant in this long, demanding Polish work a relatively satisfying and musical interpretation even if I am not Polish. Unlike a native speaker, I cannot fully connect the musical phrase with the emotion and historical associations carried by the libretto. The challenging Polish language does create diction problems for foreign singers. The appropriate musical setting of the words being sung are of course vital in any operatic production.

|

| Gunnar Arneson and Michael Moran intensely engaged in their usual interval analyses |

Friday 23.08.24 20:30

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hal

Eric Lu piano

KBS Symphony Orchestra

Pietari Inkinen conductor

Fryderyk Chopin

Piano Concerto in F minor Op. 21

|

| Bernado Bellotto, called Canaletto - View of Warsaw from the Praga district, 1770 |

This concerto, the first Chopin wrote, follows the Mozart model and was directly influenced by the style brillante of Hummel, Kalkbrenner, Moscheles or Ries. Here, in this early work, Chopin magically transforms the Classical into the Romantic style. The work itself was written 1829-30. As we all know by now, this concerto was inspired by Chopin’s infatuation, or was it youthful love, for the soprano Konstancja Gładkowska. Strangely, it was published a few years later with a dedication to Delfina Potocka.

I felt that the orchestra for this work was really rather large considering the success both Chopin concertos have had in a quintet reduction. They and their conductor Pietari Inkinen made much of the period Polish rhetorical gestures concealed within the work. These nuances are now familiar to me having lived in Poland for many years and heard the concerto many times in different hands.

The first performance of his first piano concerto took place for a group of friends in the Chopin family drawing room at the Krasiński Palace on March 3, 1830. Karol Kurpiński, the Polish composer and pedagogue, conducted a chamber ensemble. One must remember that contemporary full orchestral forces were rare in the performance of concertos in Warsaw in the early 19th century.

There are three movements

Maestoso

Lu expressed this internally iridescent style outstandingly well with great artistic refinement. The opening Maestoso (quite a favourite stylistic indication in Chopin) was noble, even rhapsodic and considered by soloist and orchestra with inner musical logic and coherence. The tempo and character was truly Maestoso. Expressive compositional details were only occasionally lost in the wash of orchestral sound. Eric in this movement grasped a fine sense of youthful excitement and thoughtful keyboard exhibitionism, just as Hummel had laid the groundwork.

The violin counterpoint and devoted cello playing emerged as affecting, highly musical instrumental sections of the orchestra. The fiorituras on the piano Lu were perfectly judged embellishments, seamlessly incorporated into the melodic lines. The LH counterpoint was inspiringly clear.

Larghetto

The outer movements of the concerto revolve like two glittering, enchanted planets around the moonlit, sublime melody of the central Larghetto movement. The nocturnal love song was inspired by the soprano Konstancja Gładowska, Chopin’s object of distant aesthetic and sensual fascination. He would soon part from her and leave Poland. As can be the way in life, it is said she preferred the attentions of the handsome, uniformed Russian officers to our poetic genius.

‘As I already have, perhaps unfortunately, my ideal, whom I faithfully serve, without having spoken to her for half a year already, of whom I dream, in remembrance of whom was created the adagio of my concerto’ (Chopin to his friend Tytus Woyciechowski, 3 October 1829).

The well-known human conflict of duty towards one’s career and love are clear. Liszt regarded the movement as ‘absolute perfection‘. Zdzisław Jachimecki, a Polish historian of music, composer and professor at the Jagiellonian University regarded it as ‘one of the most beautiful pages of erotic poetry of the nineteenth century.’

The glorious melody rose over us from like an aria or nocturne of love, full of considered poetry and lyricism. The movement contains, together with the E minor concerto Romanza, arguably the most beautiful love song ever written for piano and orchestra.

Apart from the creation of a seductive tone colour, Lu sculpted an affecting cantabile. The expressive fiorituras were graceful, elegant and grew as an organic part of the melody. There were authentic feelings of yearning for an inaccessible love here, a sensitive sense of longing. Dynamic variations were moving and persuasive, particularly when the longing turns to resentment fired by unrequited love but subsided in nuances of pianissimo resignation to the grim, rather sad reality. The pizzicato on the double basses was rather ominous and suggestive of hidden forces at work. In many ways you could say that the whole work revolves around this movement.

I always think in the Larghetto of the sentiments contained in the 1820 poem by John Keats La Belle Dame Sans Merci with its passionate interjections

I met a

lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair

was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a

garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked

at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan.

I set her

on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For

sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

That final forty-note fioritura of longing played molto con delicatezza always carries me away into Chopin’s dreamy Romantic poetical world. Lu's phrasing was most poetic.

Allegro vivace

The testing Allegro vivace provided technical challenges for everyone, especially for orchestral and soloist co-ordination. In this ebullient movement Lu brought the sensual expression of the style brillante to life but always under artistic control rather than simply a vehicle for virtuoso exhibitionism. There was energy and virtuosity in both soloist and orchestra in this Rondo final movement, composed in the exuberant style of a kujawiak dance. The youthful style brillante broke over us like the waves of the sea. The col legno on the strings was most effective in expressiveness.

The great Polish musicologist and pedagogue Mieczyław Tomaszewski writes perceptively of the movement:

It thrills us with the exuberance of a dance of kujawiak provenance. It plays with two kinds of dance gesture. The first, defined by the composer as semplice ma graziosamente, characterizes the principal theme of the Rondo, namely the refrain. A different kind of dance character – swashbuckling and truculent – is presented by the episodes, which are scored in a particularly interesting way. The first episode is bursting with energy. The second, played scherzando and rubato, brings a rustic aura. It is a cliché of merry-making in a country inn, or perhaps in front of a manor house, at a harvest festival, when the young Chopin danced till he dropped with the whole of the village. The striking of the strings with the stick of the bow, the pizzicato and the open fifths of the basses appear to show that Chopin preserved the atmosphere of those days in his memory.

How Chopin must have loved the bucolic nature of the Polish countryside and its music! The Chopin extension of the Hummel piano concerto was here fully realized. Melody and bravura figuration were wonderfully and authoritatively brought off yet with a balance of formal structure. This composition that lies between Mozart and the flowering of the style brillante was consciously created, as were the gestures towards the concertos of Weber (following the splendid horn Cor de signal ). A dazzling coda concluded an excellent performance by both soloist and orchestra.

As an encore, the poised and elegant Chopin Waltz in C-sharp minor Op.64 No.2

Jean Sibelius

Symphony No. 2 in D Major Op. 43

Carl Axel Frithiof Carpelan (1858 -1919) was a fascinating character, a Finn born in Helsinki mainly remembered as a

close friend, inspiration and supporter of the composer Jean Sibelius. His

family forbad him to study music despite him being a talented violinist and pianist.

Carpelan led a modest, obscure life, devoting himself mainly to music and

military history.

Carpelan became a close friend of Jean Sibelius after a meeting in 1890 and even created the name Finlandia which became one of the best-known compositions of the composer. The work also spread knowledge and curiosity about Finland throughout mainland Europe. Sibelius also dedicated the 2nd Symphony to him.

Carpelan arranged financial patronage for Sibelius after extensive correspondence. He arranged the finance for a visit to Italy for Sibelius. He wrote glowingly of the country to the composer of the artistic heritage of Italy as 'a country where one learns cantabile, balance and harmony, plasticity and symmetry of lines, a country where everything is beautiful – even the ugly. You remember what Italy meant for Tchaikovsky’s development and for Richard Strauss.'

|

| Carl Axel Frithiof Carpelan (1858 -1919 ) |

Sibelius hired a villa in the mountains near Rapallo and as I often emphasise concerning composers, he was inspired by the literature of the German Romantic writer Jean Paul (1763-1825). Sibelius writes:

'Jean Paul says somewhere

in Flegeljahre ('The Awkward Age' 1804-5) that

the midday moment has something ominous to it … a kind of muteness, as if

nature itself is breathlessly listening to the stealthy footsteps of something

supernatural, and at that very moment one feels a greater need for company than

ever.'

The twins, Walt and Vult, are the main

characters of Flegeljahre. They are both writers but Vult is a colourful

travelling flautist who whimsically appears and departs whilst Walt is

committed to his home life and in that way more settled in character than his

brother.

An image from Flegeljahre preoccupied Sibelius and he wrote on a sheet of paper the following imaginative vision:

'Don Juan. Sitting in the twilight in my castle, a guest enters. I ask many times who he is. – No answer. I make an effort to entertain him. He remains mute. Eventually he starts singing. At this time, Don Juan notices who he is – Death.' On the reverse side of the paper dated 2/19/01 he sketched the melody that became a theme in the second movement of the symphony.

|

The Attack Eetu Isto 1899

|

The Attack is a painting that gained a huge reputation for its political resistance during the Russification of Finland (1899–1905 and 1908–1917) |

Again, so appropriate for this fraught time of ours, after its premiere on March 8, 1902, the Symphony emerged as an emblem of national liberation. For Western Europeans the admittedly obscure history of the country indicates that the Grand Duchy of Finland was experiencing the ‘russification program’ of Tsar Nikolai II during the years 1899-1905. This attracted an emblematic interpretation of the music. Robert Kajanus, founder and conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, who put this concept into profoundly eloquent words:

'The Andante strikes one as the most broken-hearted protest against all the injustice that threatens at the present time to deprive the sun of its light and our flowers of their scent. … The scherzo gives a picture of frenetic preparation. Everyone piles his straw on the haystack, all fibers are strained and every second seems to last an hour. One senses in the contrasting trio section with its oboe motive in G-flat major what is at stake. The finale develops towards a triumphant conclusion intended to rouse in the listener a picture of lighter and confident prospects for the future.'

Overwhelmed by the sheer bravura and power of this extraordinary composition given us by the KBS Symphony Orchestra and the conducting of Pietari Inkinen, I searched for a narrative or programme feeling the vision. Not being Finnish, I was unable to fully relate deeply to the work but the sheer genius of the incredibly varied orchestration and impassioned conducting of this fine orchestra swept most rational questions away. I often feel a similar difficulty of relation of the upsurge of national feeling encapsulated in many nineteenth century Polish compositions given the fractured history of the country. Similarly to Chopin in a way, Sibelius denied a programme ever existed for his symphonies, deeming them absolute music.

For the encore a seductive and sensual interpretation of Valse triste of Sibelius (1903), eloquently conducted by Pietari Inkinen. The fine, enriching sound of this superb ensemble was again much in evidence.

Oh, and Axel Carpelan died of pneumonia in Turku in 1919. After his death, Sibelius wrote in his diary: 'For whom am I now composing?'

(Much thanks to the Finnish musicologist IIkka Oramo)

This concert is co-hosted by the Embassy of the Republic of Korea and the Korean Cultural Center in Poland in celebration of the 35th diplomatic relations between Korea and Poland.

Thursday 22.08.24 19:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Bomsori Kim violin

KBS Symphony Orchestra